In November 1979, a crisis gripped the United States as 52 Americans at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran were taken hostage by Iranian students. For 444 long days, these individuals, from junior staff to the top diplomat, remained in captivity. As the crisis stretched on for over a year, the American public desperately sought ways to express their solidarity with the hostages and their anxious families. It was during this period of national concern that the yellow ribbon emerged as a potent symbol of hope for their safe return.

But why a yellow ribbon? The answer lies in the suggestion of a diplomat’s wife, Penne Laingen, and the resonating lyrics of a popular song, the “Tie A Yellow Ribbon Song.”

Bruce Laingen Yellow Ribbon

Bruce Laingen Yellow Ribbon

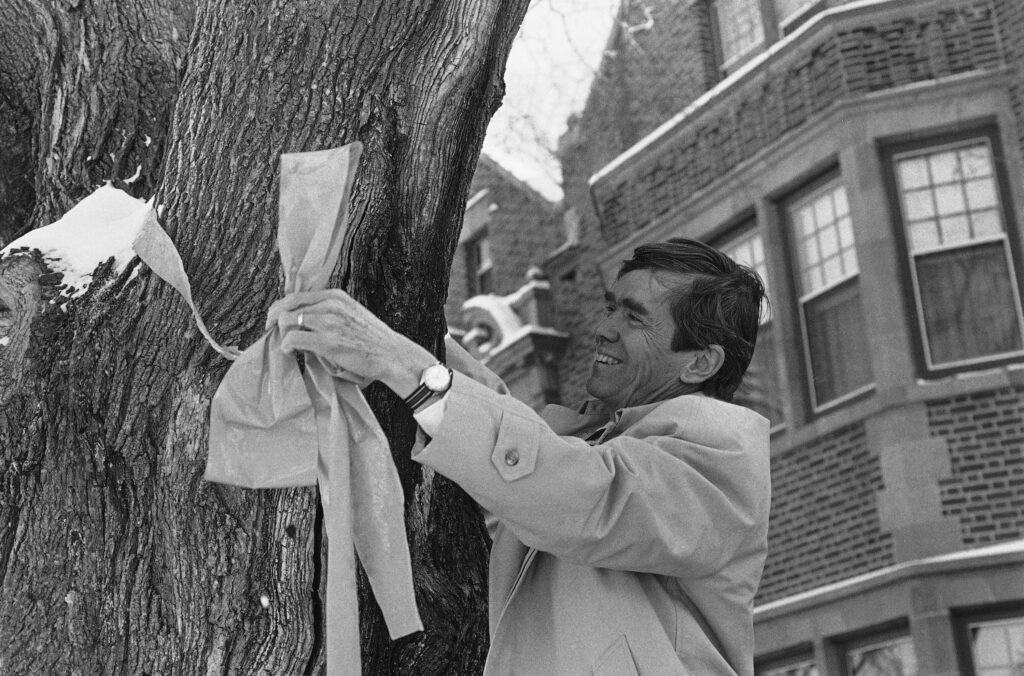

Bruce Laingen, former Chargé d’Affaires in Iran, removes a yellow ribbon after returning home from the Iran hostage crisis, symbolizing the end of the 444-day ordeal and the hope associated with the tie a yellow ribbon song.

A Symbol of National Support Emerges

Bruce Laingen, serving as the Chargé d’Affaires at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran, found himself at the heart of the crisis. As the highest-ranking official present, he became an informal leader for the hostages throughout their ordeal and even after their eventual release. His wife, Penne Laingen, also stepped into a prominent role, becoming a tireless advocate and organizer for the families of those held captive.

During an interview amidst the escalating crisis, Penne Laingen’s composed demeanor surprised a reporter who anticipated anger and outrage directed towards Iran. Penne, however, believed that displays of aggression would be counterproductive to the hostages’ well-being. In an oral history, she recounted being asked what Americans could do constructively. Her response was simple yet powerful:

“Tell them to do something constructive, because we need a great deal of patience. Just tell them to tie a yellow ribbon around the old oak tree.”

– Penne Laingen

This poignant suggestion resonated deeply. The phrase “yellow ribbon” was not arbitrary; it was a direct reference to the widely loved song, “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree.” This “tie a yellow ribbon song,” penned in 1972 and released in 1973 by Tony Orlando and Dawn, had already captured the hearts of the nation, becoming a chart-topping hit. Its appeal was so broad that it was covered by music icons like Frank Sinatra and Dolly Parton. While the song’s narrative itself wasn’t about hostage situations, its core theme of longing for reunion and hopeful anticipation of a loved one’s return struck a chord with the public, perfectly encapsulating the sentiment surrounding the hostage crisis.

Following Penne Laingen’s televised suggestion, the idea of the yellow ribbon quickly gained momentum. It began within the community of hostages’ families, and soon, it blossomed into a full-fledged cultural phenomenon. The symbol’s significance became so widely recognized that Penne Laingen was even invited to tie a yellow ribbon around the National Christmas Tree in front of the White House, further cementing its place in the national consciousness.

In 1981, amidst a surge of public inquiries about the yellow ribbon’s origins, the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center undertook a comprehensive research project to uncover the complete history and cultural context of this burgeoning symbol.

January 20, 1981: A Yellow Ribbon Welcome Home

Crowds in Frankfurt, Germany, display yellow ribbons and signs to welcome the American hostages released from Iran, reflecting the tie a yellow ribbon song’s message of homecoming.

On January 20, 1981, after enduring 444 days of captivity, the American hostages were finally released. Their first stop on the journey home was Wiesbaden, West Germany, at a U.S. Air Force base. Here, they were to undergo crucial medical evaluations and receive initial care.

Anticipation and relief poured out in the form of jubilant crowds who gathered in Germany to greet the former hostages. Homemade signs of welcome and countless yellow ribbons filled the air as they emerged from the aircraft, embodying the hopeful message of the “tie a yellow ribbon song.”

After four days in Germany, the hostages continued their journey to the United States. During their departure ceremony in Germany, even the military band joined in paying tribute to the now-iconic symbol, playing “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree” as the hostages boarded their plane. A Washington Post article at the time aptly dubbed the song the “unofficial hostage theme,” highlighting the deep connection between the “tie a yellow ribbon song” and the hostages’ return.

On January 25, 1981, the released hostages touched down on American soil at Stewart Airport, a smaller airport in New York, not far from West Point.

Upon arrival at Stewart Airport, a symbolic gesture awaited them: a literal yellow carpet was rolled out, creating a vibrant path of welcome. Ann Swift, one of the former hostages, whose “welcome home” artifacts are now part of the National Museum of American Diplomacy (NMAD) collection, received a certificate commemorating their return, which included a piece of this very yellow carpet.

Due to the immense crowds that had gathered, the typically short 20-minute drive from the airport to the hotel stretched into over an hour. The Washington Post article describing the event captured the overwhelming outpouring of emotion:

“People abandoned their cars by the hundreds and flocked to glimpse buses as they passed (…) near the end of the route, bells rang and a packed crowd of several thousand went wild as the motorcade rumbled into view…”

– Washington Post, January 26, 1981

[

New York

1981

Yellow Carpet Memento

](https://diplomacy.state.gov/items/yellow-carpet-memento/)

FROM THE COLLECTION

Yellow Carpet Memento

A certificate presented to Ann Swift by the Governor of New York—along with a section of the yellow carpet from their welcoming ceremony—commemorating the group’s arrival at Stewart Airport on January 20, 1981. Gift of Paul D. Cronin.

View the Yellow Carpet Memento

Penne and Bruce Laingen wave to crowds during the hostages’ return from Iran, greeted by yellow ribbons inspired by the tie a yellow ribbon song, symbolizing national support.

Yellow Ribbons Everywhere: A National Phenomenon

Buses carrying released hostages drive through Washington D.C. crowds waving yellow ribbons, demonstrating the nationwide adoption of the tie a yellow ribbon song’s symbolism during the Iran hostage crisis.

For over fourteen months, the hostage crisis consumed the nation, becoming a “national preoccupation,” as described in a Washington Post article just after their release. The NMAD collection holds a telegram that serves as tangible evidence of this national sentiment. This telegram vividly illustrates how employees at the Sun Valley Company in Idaho united to honor the hostages’ homecoming. The telegram read:

“Tonight, 53 employees of Sun Valley Company, each bearing a brightly lit torch, skied down Idaho’s magnificent Mount Baldy mountain in celebration of your joyous return to the USA. That flaming yellow ribbon, winding through tree-lined trails, was cheered by residents and guests of the sister communities of Sun Valley and Ketchum, Idaho.”

A telegram from Sun Valley Company showcasing national support for the returning hostages with a “flaming yellow ribbon” ski display, inspired by the tie a yellow ribbon song phenomenon.

By the time the hostage crisis concluded, the yellow ribbon, inspired by the “tie a yellow ribbon song,” had become a ubiquitous national symbol. Its presence even extended to the Super Bowl, a major national event. Coincidentally, the Super Bowl that year fell on January 25th, the very day the hostages arrived back in the United States. A giant yellow ribbon adorned the Superdome in New Orleans, cheerleaders waved yellow streamers, and players sported yellow stripes on their helmets – a powerful visual representation of the nation’s collective hope and welcome, all echoing the sentiment of the “tie a yellow ribbon song.”

The Frontlines of Diplomacy and Enduring Symbolism

This story of the yellow ribbon and the “tie a yellow ribbon song” serves as a poignant reminder of the challenging and often perilous work undertaken by diplomats serving abroad. It is through the stories and artifacts generously shared by the diplomatic community that we are able to recount these significant moments in history. We express our sincere gratitude to Bruce Laingen, Ann Swift’s husband Paul Cronin, John Limbert, Kate Koob, and Roy Apel for their invaluable artifact donations, and to all diplomats for their dedicated service.

Support the National Museum of American Diplomacy

Interested in supporting our museum and the stories of diplomacy? The museum is seeking support to complete the development and construction of our permanent exhibits. Click here to find out how you can support the museum.

References