Country music has a long and storied tradition of exploring heartbreak and sorrow. From the early hillbilly sounds of the 1920s to the honky-tonk anthems of the ’40s and ’50s, the rebellious Bakersfield sound of the ’60s, and the outlaw country movement of the ’70s, these genres have consistently delivered songs that resonate with our deepest sadness. This legacy continues to thrive today, even as country music evolves with contemporary production and sonic landscapes. Here, we delve into 40 of the saddest country songs ever recorded, each a poignant masterpiece guaranteed to bring a tear to your eye.

Patsy Cline, “I Fall to Pieces”

Hank Cochran and Harlan Howard penned “I Fall to Pieces” with hit potential in mind, but before it found its way to Patsy Cline, Brenda Lee deemed it “too country,” and Roy Drusky considered it “too feminine.” However, fate intervened when Drusky left the studio, and Cline seized the opportunity. As Drusky recounted, Cline declared, “Drusky, that’s a hit song you just let go, and I’m gonna get Owen [Bradley, Decca producer] to let me have it.” Jan Howard, Harlan’s wife, offered a different version, suggesting Cline initially disliked the song and resisted recording it. Regardless of the initial hesitation, “I Fall to Pieces” was recorded in late 1960 and became Cline’s biggest country hit the following year. The song’s understated honky-tonk rhythm belies the emotional turmoil as Cline portrays a woman desperately trying to maintain composure in the presence of a former lover who now only desires friendship.

Alan Jackson, “Monday Morning Church”

Brent Baxter, the lyricist behind “Monday Morning Church,” drew inspiration from his English teacher mother, who used the phrase “as empty as a Monday morning church” to illustrate poetry to her students. Set against a simple yet timeless melody by Erin Enderlin, Baxter employed this metaphor to depict the profound grief of a widower grappling with anger towards God. Lee Ann Womack and Terri Clark considered the song before Alan Jackson, known for his aversion to melodrama, became its definitive interpreter. Jackson’s understatedly desperate delivery, enhanced by Patty Loveless’s backing vocals, evokes a sense of a man teetering on the brink of despair.

George Jones, “The Grand Tour”

Trying to rank George Jones’ sad songs by their level of sorrow is a near-impossible task. “The Grand Tour,” a heartbreaking narrative of a husband’s walk through his deserted home immediately after his wife’s departure, marks a pivotal moment in Jones’ career. It was here that he first collaborated with Epic Records producer Billy Sherrill. Sherrill’s signature string arrangements, initially viewed as contradictory to Jones’ honky-tonk roots, ultimately framed and amplified the king of country’s isolation. The song is often interpreted as a reflection of Jones’ painful divorce from country icon Tammy Wynette, finalized in the same year of its release. Adding another layer of complexity, one of the song’s co-writers was George Richey, who would later marry Wynette.

Pirates of the Mississippi, “Feed Jake”

“Feed Jake” by Pirates of the Mississippi, a band from the early Nineties, centers on the poignant image of a man kneeling to recite the “Now I Lay Me Down to Sleep” prayer, imploring someone to care for his beloved dog, Jake, should he die in his sleep. However, “Feed Jake” transcends the typical ballad of a pet in need. Remarkably forward-thinking for a country song from 1991, “Feed Jake” advocates for the rights of the homeless and expresses solidarity with the LGBTQ+ community. The lyrics challenge societal judgments, questioning whether superficial distinctions truly matter: “Now, if you get an ear pierced, some will call you gay/But if you drive a pick-up, they’ll say, ‘No, you must be straight’/What we are and what we ain’t, what we can and what we can’t/Does it really matter?”

Martina McBride, “God’s Will”

A classic within country music’s enduring subgenre of songs that remind you “You-Think-You’ve-Got-Problems,” Martina McBride’s “God’s Will” is a slow-building piano ballad and the emotional peak of her 2003 album Martina. The song celebrates a young boy who, despite wearing leg braces, maintains an unwavering, bright smile. Written by Barry Dean and Tom Douglas, inspired by Dean’s daughter, the lyrics deliver a series of emotionally resonant moments, reminiscent of Forrest Gump, painting a picture of quiet resilience: “‘Hey Jude’ was his favorite song/At dinner he’d ask to pray/And then he’d pray for everybody in the world but him.”

Charley Pride, “Where Do I Put Her Memory”

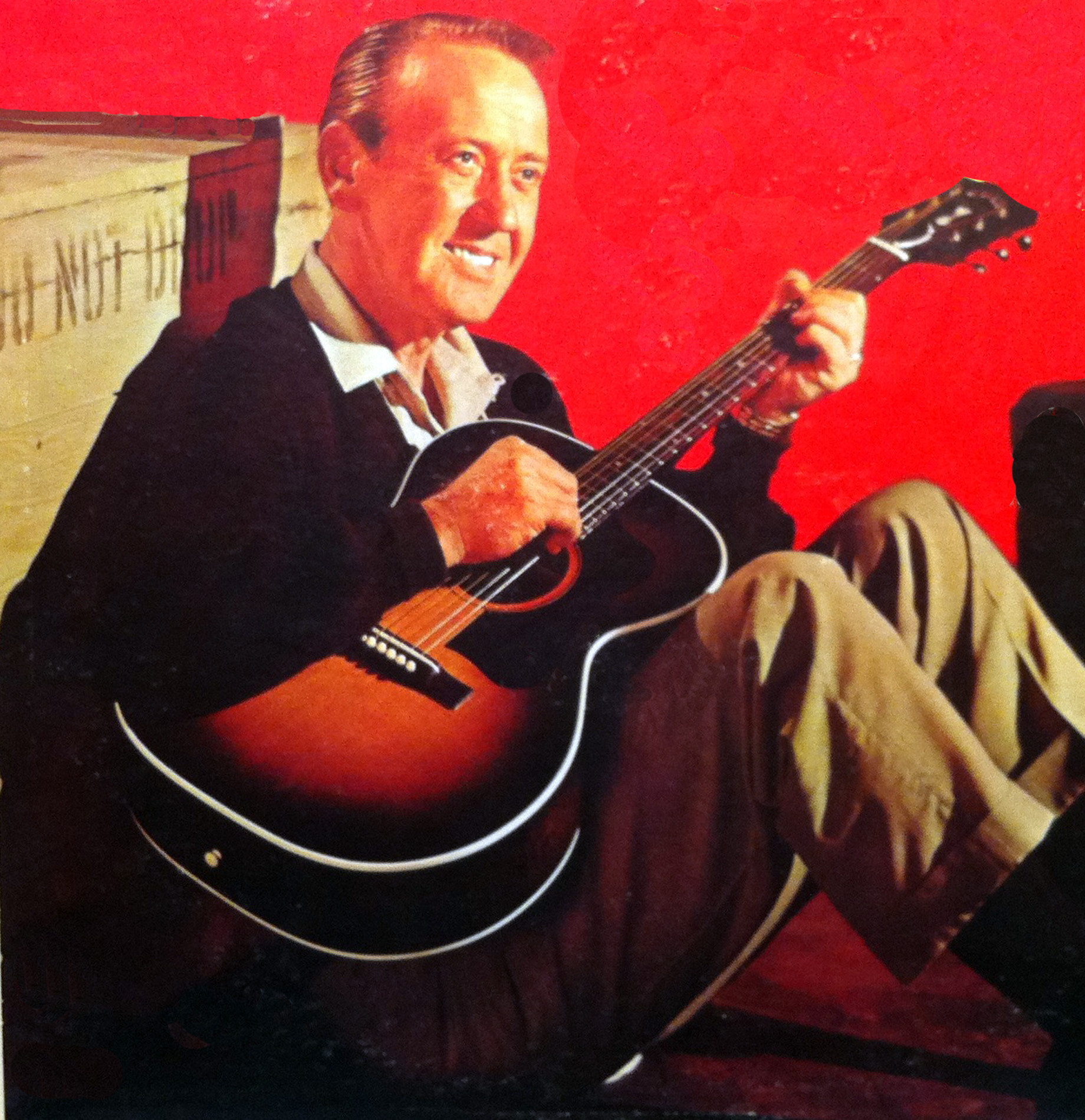

Charley Pride, country singer

Charley Pride, country singer

Jim Weatherley’s composition, brought to life by Charley Pride, “Where Do I Put Her Memory,” never explicitly states the fate of the woman whose memory the narrator struggles to put aside. Yet, Pride’s emotive delivery leaves little doubt that she has likely passed away. The song, which became his 21st Number One hit on the Country chart in 1979, details the lingering presence of a lost love in everyday objects. Gifts, her pillow, and her clothes are typical reminders, but the lyrics reach a profound level of heartbreak with the simple, devastatingly realistic mention of picking up “her hairpins and curlers/That she dropped on her side of the bed.”

Gene Autry, “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine”

Gene Autry, the Singing Cowboy, achieved his breakthrough hit in 1931 with “That Silver-Haired Daddy of Mine,” co-written with Jimmy Long at a railroad depot. This gentle, pre-eulogy apology to his father for causing worry became the first-ever Gold record, a hopefully meaningful consolation. Over eight decades later, the song has been interpreted by a diverse range of artists, from Simon & Garfunkel’s delicate rendition to Jim Reeves’ authoritative version, Johnny Cash’s reverent take, the Everly Brothers’ intricate harmony, Sesame Street‘s furry blue version, and even Billie Joe Armstrong and Norah Jones’ unexpected collaboration.

Brooks & Dunn, “Believe”

“Believe,” a tender, soulful, organ-infused eulogy, stands out on Brooks & Dunn’s otherwise boisterous 2005 album Hillbilly Deluxe. The song tells the poignant story of “Old Man Wrigley” (unrelated to the Chicago Cubs), a widower patiently awaiting reunion with his wife and son in the afterlife. After collaborating with renowned songwriter Craig Wiseman, Ronnie Dunn delivered a powerfully emotive vocal performance, imbued with preacher-like conviction. While it modestly entered the country Top 10, “Believe” achieved greater recognition, winning the 2006 CMA for Song of the Year.

Merle Haggard, “Sing Me Back Home”

Merle Haggard’s sentimentality in “Sing Me Back Home,” released in 1967, possesses a raw toughness, reflecting its real-life inspiration. The song serves as a eulogy for fellow San Quentin inmate “Rabbit” Hendricks, who was sentenced to the gas chamber for killing a police officer during a failed escape. One can only imagine the deeply moving last song requested by the death row inmate, performed by his “guitar-playing friend.”

Townes Van Zandt, “Waiting Around to Die”

“This is the first serious song I ever wrote,” Townes Van Zandt confessed to his audience before performing “Waiting Around to Die” from his 1973 record Live at the Old Quarter. Originally featured on 1968’s For the Sake of the Song, it’s a somber narrative of a boozy wanderer struggling to find purpose in a life he sees as leading only to oblivion. The song concludes with the bleak couplet: “His name’s Codeine, he’s the nicest thing I’ve seen/Together we’re going to wait around and die.” The song is delicately heartbreaking and eerily foreshadows Van Zandt’s own premature death at 52 due to alcoholism. Despite its profound impact, Van Zandt hesitated to perform it live, stating, as he said, “Nobody wants to hear blues on blues on blues.” Yet, audiences did connect with its raw emotion. “That’s what music’s all about, when you hear something and you don’t really have a choice,” Alex Turner of Arctic Monkeys observed regarding Van Zandt’s work, “but to think, ‘Oh fuck, all right, I’m going there.’”

Mary Gauthier, “Mercy Now”

Mary Gauthier embarked on her music career at 35, after overcoming struggles with alcoholism and drug addiction. She quickly established herself with her 2005 major label debut, Mercy Now, showcasing a remarkable talent for storytelling and creating characters that subtly reflect the human condition. In the title track, “Mercy Now,” Gauthier seeks forgiveness and compassion across different scales, from the personal to the global, employing a lyrical structure inspired by Lucinda Williams’ “I Changed the Locks.” “[S]he has said](https://www.oneradsong.com/2012/07/mercy-now-by-mary-gauthier.html). “I played it for my publisher and it was received with a yawn, and I think that threw me off. Once people started responding to it, I realized I might need a new publisher.”

Tim McGraw, “If You’re Reading This”

Inspired by a magazine article about war casualties, Tim McGraw collaborated with Brad and Brett Warren to write “If You’re Reading This” in spring 2007. The song is structured as a letter from a soldier, written in anticipation of his potential death in combat, with personal farewells to his mother, father, and wife. McGraw premiered the song at the ACM Awards in May 2007, joined on stage by families who had lost loved ones in military service. Radio stations began playing a bootlegged version, and its popularity grew rapidly, prompting McGraw’s label to officially release it.

Steve Wariner, “Holes in the Floor of Heaven”

Steve Wariner Saddest Country Songs

Steve Wariner Saddest Country Songs

Steve Wariner’s poignant ballad, “Holes in the Floor of Heaven,” explores themes of loss, grief, and faith. The protagonist endures the deaths of both his grandmother and his young wife, who tragically passes away after childbirth. To find solace, he is told that rain signifies “holes in the floor of heaven and her tears are pouring down. That’s how you know she’s watching, wishing she could be here now.” The song culminates with their daughter’s wedding day, marked by rain. Wariner clarified that the lyrics, while emotionally resonant, weren’t entirely autobiographical. “I had just lost my grandmother not long before that,” Wariner shared with CMT. “Billy [Kirsch, co-songwriter] and I were both drawing on the perspective of our grandparents for the first verse. And then just kind of used our creative liberty to paint the picture.”

Red Sovine, “Teddy Bear”

Red Sovine is known for “Phantom 309,” a song about a hitchhiker’s supernatural encounter with a trucker named Big Joe. In “Teddy Bear,” arguably his saddest song, Sovine portrays a CB radio conversation with a lonely, “crippled and can’t walk” boy. Eventually, he gives the boy a ride in his truck. The boy’s mother calls to express her gratitude, and Sovine concludes the song with a tearful sign-off: “I’ll sign off now, before I start to cry/May God ride with ya’, 10-4 goodbye.” “My ol’ friend Teddy Bear” later reappears in Sovine’s “Little Joe,” about a loyal dog who helps the same narrator after a storm-induced accident leaves him blind.

Dwight Yoakam, “I Sang Dixie”

Though Dwight Yoakam emerged as a West Coast cowpunk artist, his Kentucky roots remain deeply embedded in his music. “I Sang Dixie,” with its mournful fiddle and somber tone, evokes the sorrow of a Civil War lament. It recounts the lonely death of a vagrant on a “damned old L.A. street,” concluding with the solace, “No more pain, and now he’s safe back home in Dixie.” This is one of several homesick songs Yoakam penned after inspiring visits to his home state, keeping it in his repertoire for nearly a decade before its release. Pete Anderson, Yoakam’s producer and guitarist, considered it a sure hit. “I thought it was his best song… a Number One record,” Anderson stated in Don McCleese’s 2012 Yoakam biography A Thousand Miles From Nowhere. He was proven right. Released as a single from 1988’s dark Buenos Noches From a Lonely Room, “Dixie” became Yoakam’s second Number One hit.

Doug Supernaw, “I Don’t Call Him Daddy”

“I Don’t Call Him Daddy” narrates the story of a divorced couple and their young son caught in the middle. In the father’s absence, the mother’s new live-in boyfriend “takes care of things.” Despite this, the little boy refuses to call him “Daddy,” loyally insisting, “he can never be like you.” Written by Reed Nielsen, Kenny Rogers first recorded “I Don’t Call Him Daddy” and released it as a single in 1987, but it didn’t reach the country Top 40. Doug Supernaw’s version, however, topped the charts for two weeks in December 1993. In a sad irony, Supernaw later faced legal issues for failure to pay child support.

Ray Charles & Willie Nelson, “Seven Spanish Angels”

During a career slump in the late Seventies, Ray Charles found unexpected appreciation in Nashville. A duet with Clint Eastwood, “Beers to You,” reached the country Top 50, a performance at the Loretta Lynn Opry was a hit, and his 1980 Hee Haw appearance was so successful that Buck Owens joked about him becoming a regular. This prediction came true. In 1983 and ’84, Charles recorded his first two country albums since Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music, and in March 1985, his duet with Willie Nelson, “Seven Spanish Angels,” became his first Number One hit since 1966. “Seven Spanish Angels,” a gunfighter ballad reminiscent of Marty Robbins, tells the tale of Mexican bandits killed by bounty hunters pursuing them to Texas. After the man is shot attempting to escape, the woman aims his empty gun at their attackers, ensuring she shares his fate.

Rascal Flatts, “Skin (Sara Beth)”

Rascal Flatts tackle a deeply sensitive topic in “Skin (Sara Beth),” addressing a pain that surpasses even “What Hurts the Most.” For a Kentucky teenager, the challenges of cancer and chemotherapy disrupt normalcy in this ballad (originally a hidden track on 2005’s Feels Like Today) which reached Number Two on the Billboard Hot Country Songs chart. Strings, piano, light pedal steel, and Gary LeVox’s earnest vocals convey her fear of attending prom without hair. Her date thoughtfully alleviates her anxiety by shaving his own head, creating a touching resolution.

Lucinda Williams, “Sweet Old World”

“Sweet Old World,” written as a tribute to a friend who committed suicide, is a standout track from Lucinda Williams’ 1992 album of the same name. The album explores themes of life, death, and legacy. Williams began writing the song in 1979 after poet Frank Stanford’s suicide, but it remained unreleased for over 13 years. Williams told the New Yorker she withheld the ballad “because my career has been distinguished by other people, who have always been men, telling me what I should sound like.” Sonically simple, Williams’ vocals resonate in an empty space, filled with both sadness and anger.

Vern Gosdin, “Chiseled in Stone”

Vern “The Voice” Gosdin’s tearful ballad, “Chiseled in Stone,” directly targets the heartstrings. Characterized by gospel harmonies and somewhat elaborate production, this 1989 Country Music Association Song of the Year details the aftermath of a lovers’ quarrel, described as “another piece of heaven gone to hell.” As the heartbroken man seeks solace in alcohol, an older figure reminds him of deeper sorrows: “You don’t know about sadness, ’til you face life alone/You don’t know about lonely ’til it’s chiseled in stone.” The message is a stark reminder to appreciate what remains, as loss can be far more profound.

Dolly Parton, “I Will Forever Hate Roses”

UNITED KINGDOM – JULY 05: O2 ARENA Photo of Dolly PARTON, Dolly Parton performing on stage (Photo by Harry Scott/Redferns)

UNITED KINGDOM – JULY 05: O2 ARENA Photo of Dolly PARTON, Dolly Parton performing on stage (Photo by Harry Scott/Redferns)

The red rose, a pervasive symbol of romance, often verging on cliché, is given a fresh, sorrowful perspective by Dolly Parton in “I Will Forever Hate Roses.” In this song, roses accompany a curt goodbye note from a departing lover, leading Parton to discover the inherent pain beneath the surface of romantic symbols: every rose has its thorn, much like every cowboy sings a sad song.

Mel Tillis, “Life Turned Her That Way”

Songwriting luminary Harlan Howard, who famously defined country music as “three chords and the truth,” masterfully balances sympathy and subtle condescension in “Life Turned Her That Way.” This song offers a keen observation of how heartbreak can transform a woman into someone “cold and bitter.” Little Jimmy Dickens first recorded it, and Ricky Shelton had a Number One hit with it. However, Mel Tillis’ 1967 version, marked by his restrained delivery and stately piano accompaniment, mines the lyric for its maximum emotional impact.

Ray Price, “For the Good Times”

Ray Price’s introduction to Kris Kristofferson occurred when Kristofferson was a janitor at Columbia Studios. Price didn’t recall the songwriter’s name until hearing the demo for “For the Good Times” during a 1969 tour. Beginning with the line “Don’t be so sad,” the song evolves into a poignant depiction of a relationship’s final moments, culminating in the chorus, “Hear the whisper of the raindrops blowing soft against the window/And make believe you love me one more time/For the good times.” Price was immediately captivated, though Columbia initially released his version as a B-side. Nevertheless, by 1970, “For the Good Times” became the biggest country hit of the year, later becoming a pop standard covered by artists including Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra, Johnny Cash, and Michael Jackson.

Vince Gill, “Go Rest High on That Mountain”

Though evocative of a timeless standard, Vince Gill wrote “Go Rest High on That Mountain” in 1994, inspired by Keith Whitley’s death from alcoholism in 1989. Gill began writing it after Whitley’s passing but completed it after his own brother’s death in 1993. Despite its somber origins and themes of loss, the song is noted for its spiritually uplifting tone. It resonated widely, winning two Grammys and the BMI award for “Most Performed Song” in 1997.

Willie Nelson, “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain”

Willie Nelson had long been a successful songwriter for others, including Patsy Cline and Frank Sinatra. However, it was a cover song that established him as a leading singer: “Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain,” written by Fred Rose in 1945 and previously recorded by Roy Acuff, Hank Williams, and Conway Twitty, among others. Nelson’s rendition is perhaps the most minimalist, featuring only guitar, accordion, and his distinctive, wounded vocal style, creating a sepia-toned portrait of farewell.

“Blue Eyes Crying in the Rain” was central to Nelson’s 1975 concept album Red Headed Stranger, and quickly topped charts, becoming the definitive version. Even artists like The Reivers and UB40 have since covered it. Legend has it that it was the last song Elvis Presley played on his piano at Graceland before his death in 1977.

Dixie Chicks, “Travelin’ Soldier”

Austin-based singer-songwriter Bruce Robison wrote “Travelin’ Soldier” after a friend was deployed in the first Iraq War. Robison released his initial version of this tragic love story—about two teenagers whose budding romance is overshadowed by the Vietnam War—in the mid-Nineties. It became a chart-topping hit in 2003 when the Dixie Chicks re-recorded it, its themes resonating anew. The song’s climax occurs at a Friday night football game, where the young man’s name is read aloud as part of a prayer for local Vietnam War casualties. The young waitress, his love interest, is found “crying all alone under the stands,” grieving not only her lost love but also the shattered dream of “never more to be alone, when the letter said, the soldier’s coming home.” Shortly after its chart success, controversy arose when Natalie Maines expressed shame that President Bush was from Texas. In the following two weeks, “Travelin’ Soldier” rapidly fell from the charts.

Merle Haggard, “If We Make It Through December”

Released in October 1973, “If We Make It Through December” tells the story of a factory worker laid off before Christmas, burdened by the inability to provide holiday cheer for his daughter. Amidst high unemployment and inflation in 1973, and shortages of oil and steel, America was in a significant recession. Haggard’s song transcended headlines about economic woes, focusing on the human impact. It also conveyed a sense of resilience: “If we make it through December, we’ll be fine.” This resonated deeply, making the song a Number One country hit that December, and ensuring its enduring appeal beyond the holiday season.

Lee Brice, “I Drive Your Truck”

Image Credit: Lisa Lake/Getty Images

In the 21st century, country ballads often blend with power ballad conventions, distinguished by rural signifiers—in this case, a Braves hat, a field, a truck, and attention to gas mileage. Inspired by a father who kept his son’s Dodge truck after his son was killed in Afghanistan, “I Drive Your Truck” explores how we maintain connection to lost loved ones through their possessions, and particularly how men process grief. “You’d probably punch my arm right now if you saw this tear rollin’ down on my face,” Brice sings. “Hey, man I’m tryin’ to be tough.” Given the option to visit his son’s grave, the father chooses to drive the truck instead. The song serves as an emotional outlet in ways he feels unable to express directly.

Shelby Lynne, “Heaven’s Only Days Down the Road”

Shelby Lynne Saddest Country Songs

Shelby Lynne Saddest Country Songs

“Heavy” is an understatement for Shelby Lynne’s acoustic rendition of her traumatic family history in “Heaven’s Only Days Down the Road,” from her 2011 album Revelation Road. The song revisits 1986, when Lynne was 17 and her estranged, alcoholic father murdered her mother before taking his own life. This gripping murder ballad delves into her father’s psyche (“Load up the gun full of regret/I ain’t even pulled the trigger yet”) and ultimately suggests that Lynne and her younger sister, fellow country artist Allison Moorer, are better off in the aftermath. Two gunshots punctuate the song’s devastating conclusion.

Alan Jackson, “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)”

Written in response to the September 11th, 2001 terrorist attacks, “Where Were You (When the World Stopped Turning)” stands as a profoundly relatable song of national mourning. Alan Jackson began writing it as a way to process the events, and initially hesitated to release it publicly, fearing exploitation of tragedy and feeling it was too personal. However, encouraged by family and record label colleagues, Jackson debuted it at the 35th Annual CMA Awards in November 2001, receiving an emotional standing ovation. Jackson’s expression of collective helplessness resonated deeply, keeping the song atop the charts for five weeks. Its significance was further recognized on November 16th, 2001, when Georgia Congressman Mac Collins honored the song on the U.S. House floor, placing it in the Congressional Record.

Red Foley, “Old Shep”

Red Foley Saddest Country Songs

Red Foley Saddest Country Songs

Chekhov’s gun principle applies to dogs in country songs: a dog introduced in the first verse is likely to die by the end. “Old Shep,” written and first recorded by Red Foley in 1931 (and performed by a young Elvis Presley in 1945), is based on Foley’s childhood dog. As Shep ages and weakens, the vet advises putting him down. The narrator considers shooting him, like Old Yeller, but “just couldn’t do it, I wanted to run/And I wished that they’d shoot me instead.” Instead, Old Shep rests his head on the boy’s knee, looks at him knowingly, and peacefully passes away. The final verse offers solace, depicting Doggie Heaven where “Old Shep has a wonderful home.”

Lefty Frizzell, “Long Black Veil”

Recorded during the rise of the Nashville Sound, “Long Black Veil” was a stylistic departure for honky-tonk singer Lefty Frizzell. Amidst weeping steel guitar and gentle rhythms, Frizzell narrates the tale of a man wrongly accused of murder. He cannot provide an alibi without revealing his affair with his best friend’s wife, leading to his execution and the secret buried with him. The most heart-wrenching moment belongs to his lover, grieving in the night. “Nobody knows but me,” Frizzell sings with his gentle twang. Danny Dill and Marijohn Wilkin, the songwriters, drew inspiration partly from a veiled woman who frequently visited Rudolph Valentino’s grave.

Reba McEntire, “She Thinks His Name Was John”

Similar to the somber second verse of TLC’s “Waterfalls,” Reba McEntire’s 1994 tearjerker, “She Thinks His Name Was John,” directly addresses the AIDS/HIV crisis. A casual encounter results in a young woman’s tragic fate: “She let a stranger kill her hopes and her dreams.” Written by Steve Rosen and Sandy Knox, whose brother died of AIDS after a 1979 blood transfusion, this powerful ballad reached Number 15 on Billboard‘s Hot Country Songs chart, becoming country music’s most prominent response to the AIDS crisis.

Faron Young, “Hello Walls”

Honky-tonk star Faron Young encountered “Hello Walls” at Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge near the Grand Ole Opry. A struggling songwriter with rejected demos played him the song. Its melody conveyed loneliness even without understanding the lyrics. “Hello Walls” became a major crossover hit for Young and launched the career of the young songwriter, Willie Nelson.

Johnny Cash, “Sunday Morning Coming Down”

No song captures the feeling of waking up hungover and alone quite like “Sunday Morning Coming Down.” Kris Kristofferson wrote it in a condemned Music Row tenement after his wife left, taking their daughter. “Sunday was the worst day of the week if you didn’t have a family,” Kristofferson told biographer John Morthland. “The bars were closed until 1 in the afternoon… so there was nothing to do all morning.” Ray Stevens first recorded “Sunday,” but Johnny Cash’s version, imbued with pathos appropriate for lines like “nothin’ short of dyin’ that’s half as lonesome as the sound,” reached Number One. “Actually,” Kristofferson told NPR, “it was the song that allowed me to quit working for a living.”

John Michael Montgomery, “The Little Girl”

John Michael Montgomery’s “The Little Girl” narrates a devastating family tragedy. This last Number One Billboard Hot Country Song of his career depicts a young girl hiding from her parents’ violent argument, fueled by drug abuse and alcoholism, with fatal consequences. Backed by harmonies from bluegrass stars Alison Krauss and Dan Tyminski and an emotionally charged arrangement, Montgomery maintains a steady delivery as the story reaches its spiritual conclusion.

George Jones, “He Stopped Loving Her Today”

Written by the same team behind Tammy Wynette’s “D-I-V-O-R-C-E,” “He Stopped Loving Her Today” is arguably country music’s most impactful punchline song. With vivid detail, it describes a man whose enduring love is finally reciprocated—at his funeral. The song perfectly suits George Jones’ anguished voice, making it hard to imagine anyone else singing it. Yet, it almost didn’t happen.

In Bob Allen’s 1996 Jones biography The Life and Times of a Honky Tonk Legend, producer Billy Sherrill recounted that Jones “hated the melody and wouldn’t learn it” deeming it “too long, too sad, too depressing.” Even after relenting, Jones grumbled that, “Nobody’ll buy that morbid son of a bitch.” Instead, “He Stopped Loving Her Today” became Jones’ first chart-topper since 1974, revitalizing his career.

Brad Paisley and Alison Krauss, “Whiskey Lullaby”

Brad Paisley and Alison Krauss, known for their comedic talents, deliver profound sadness in “Whiskey Lullaby,” a duet from Paisley’s 2003 Mud on the Tires. This tragic love song depicts two individuals drinking themselves to death, verse by verse. Written by Bill Anderson and Jon Randall, it reached the country Top Five and won the ACM Award for Vocal Event of the Year. The music video intensifies the pathos, packing a Lifetime movie’s worth of emotion into its opening minutes.

Hank Williams, “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry”

Hank Williams’ “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry” is not only one of country music’s most evocative lyrics but also a poignant portrayal of clinical depression. Everything the singer observes—from a robin’s cry to a train’s whistle, to the silent fall of a star—mirrors his despondent state. Williams initially considered it a poem for his alter ego “Luke the Drifter.” Fortunately, he reconsidered. Without the gentle melody softening its tone, what Elvis Presley introduced as “probably the saddest song I’ve ever heard” at his 1973 Hawaii concert might have been too overwhelmingly bleak.

Martina McBride, “Concrete Angel”

Martina McBride has been a prominent voice against abuse in country music. While “Independence Day” addresses spousal abuse, “Concrete Angel” (from her Greatest Hits album) focuses on child abuse: “She hides the bruises with linen and lace.” The song describes a child suffering abuse at her mother’s hands, with neighbors passively ignoring her cries. While the song ends tragically with the child’s death (the “concrete angel” is a gravestone), its impact is positive. “[S]aid co-writer Rob Crosby](https://web.archive.org/web/20080412081132/https://www.storybehindthesong.net/read/story/86). “The fact that a few kids have seen the music video, which flashes the number for Child Help USA, and have been able to escape a bad situation is a gratifying thing.”