The song “Kumbaya,” often associated with campfires and simple harmonies, carries a far more profound and complex history than many realize. Far from being a simple children’s song, “Kumbaya” is a deeply rooted African American spiritual with origins stretching back to the early 20th century and connections to the Gullah Geechee culture of the southeastern United States. This exploration delves into the fascinating journey of the “Kumbaya Kumbaya Song,” tracing its evolution from early recordings to its place in the folk revival movement and beyond.

Pictured at the Library of Congress on December 2, 2010, Freddie Palmer with the McIntosh County Shouters, a Gullah singing group known for spirituals including “Kumbaya.” Photo by Stephen Winick.

While “Kumbaya” has faced misinterpretations and even mockery in recent decades, often caricatured as a symbol of simplistic unity or ineffective consensus, its origins are anything but trivial. The song’s journey from a heartfelt spiritual plea to a globally recognized, yet sometimes misunderstood, folk song is a testament to the power of music and the complexities of cultural exchange.

Unearthing the Earliest Traces of “Kumbaya Kumbaya Song”

To understand the true history of the “kumbaya kumbaya song,” we turn to invaluable resources like the American Folklife Center Archive at the Library of Congress. This archive holds some of the earliest documented evidence of the song, including sound recordings and manuscripts that predate its popularization during the folk revival era. These primary sources help to dispel misconceptions surrounding the song’s origins and offer a more accurate account of its development.

One persistent myth is that “Kumbaya” originated in Africa, often attributed to missionary influence in Angola. Another theory credits Anglo-American composer Marvin Frey as the originator, pointing to his 1939 copyrighted song “Come by Here.” However, archival discoveries reveal a different narrative, one deeply intertwined with African American musical traditions in the American South.

The Boyd Manuscript: A 1926 Glimpse into “Come By Here”

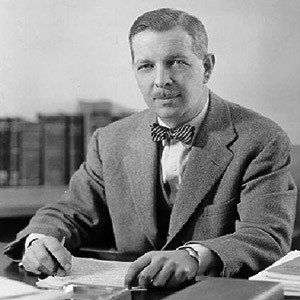

Julian Parks Boyd, a key figure in early “Kumbaya” song documentation. Photo from AFC Subject Files.

Among the earliest records in the AFC archive is a manuscript sent to Robert Winslow Gordon, the archive’s founder, in 1927. Collected by Julian Parks Boyd, then a high school principal, from his student Minnie Lee in North Carolina in 1926, this version is titled “Oh, Lord, Won’t You Come By Here.” The lyrics, featuring repeated lines like “Somebody’s sick, Lord, come by here,” “Somebody’s dying, Lord, come by here,” and “Somebody’s in trouble, Lord, come by here,” clearly mark it as a precursor to the “kumbaya kumbaya song” we know today.

Boyd’s story itself is a fascinating side note in the history of “kumbaya kumbaya song.” His brief foray into folklore collection was cut short by community disapproval, leading him away from folksong and towards a distinguished career as a historian and librarian. Despite this shift, his contribution to preserving early versions of spirituals like “Come By Here” remains significant. His manuscript provides crucial evidence that the song existed and was being sung in African American communities well before the commonly cited origins.

Cylinder Recordings: Hearing “Come By Here” in 1926

Robert Winslow Gordon, the pioneering archivist who captured early “Kumbaya” recordings on cylinder. Library of Congress photo, circa 1930.

Even more remarkable than the Boyd manuscript is the discovery of cylinder recordings from the same era within the AFC archive. Among Robert Winslow Gordon’s initial collections were cylinder recordings of spirituals with the refrain “come by here” or “come by yuh,” collected during his Georgia trips between 1926 and 1928. One surviving cylinder, after others were lost or broken, provides what is believed to be the earliest known sound recording of the “kumbaya kumbaya song.”

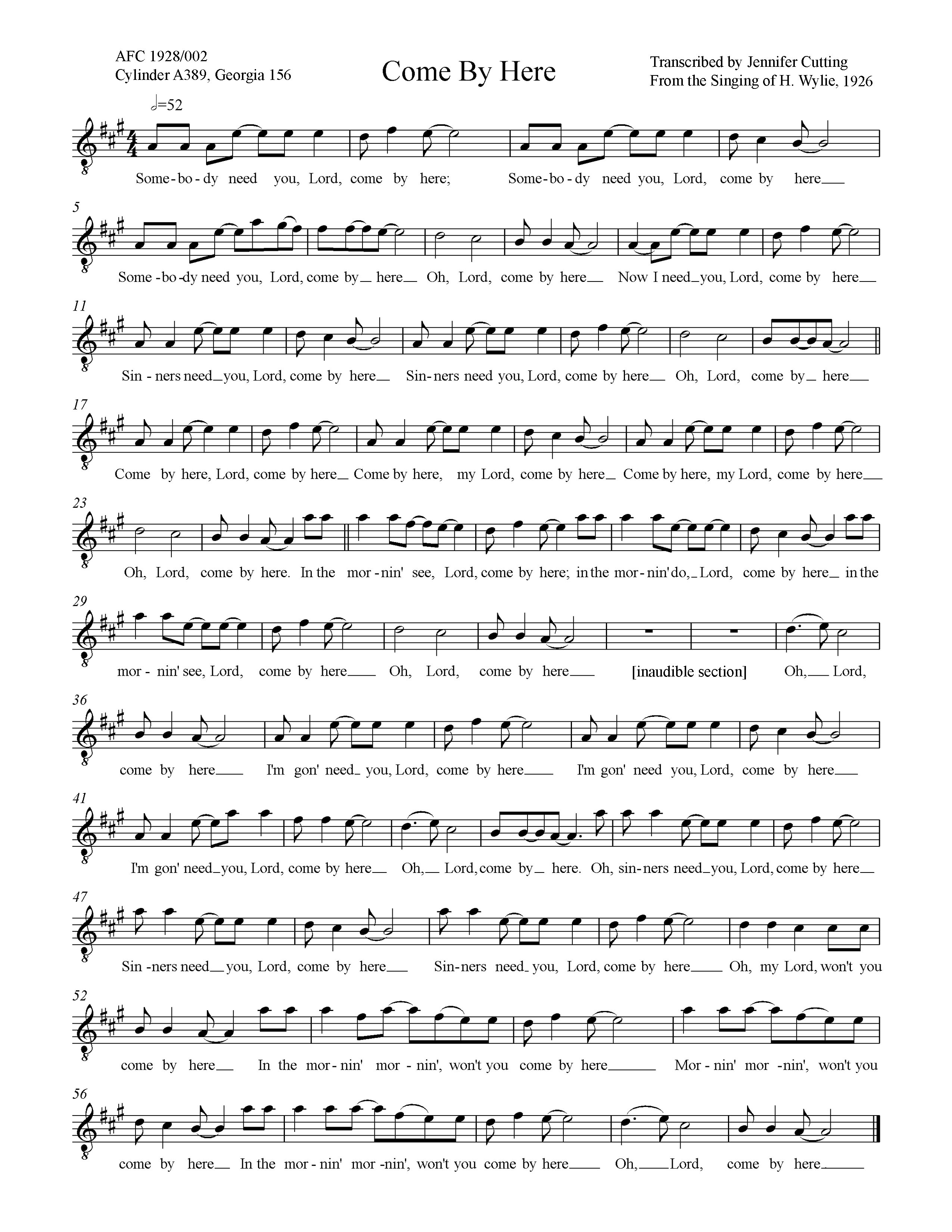

This cylinder features a recording of “Come by Here” sung by H. Wylie, recorded in Darien, Georgia, likely in April 1926. Gordon’s faint voice at the end of the cylinder confirms details: “Sung by Henry Wylie, Darien, Georgia, April the seventeenth….” The transcribed lyrics and musical notation reveal a song strikingly similar to later versions of “Kumbaya,” using phrases like “Need you Lord, come by here” and “Sinners need you, Lord, come by here,” punctuated by the refrain “Oh, Lord, come by here.”

Research into Henry Wylie suggests he was an African American man living in coastal Georgia, working as a boat hand. This context further strengthens the link between “kumbaya kumbaya song” and African American spiritual traditions in the region.

Early Publications and Broadening Reach

The 1920s and 1930s saw “Come by Here” or similar songs emerge in various forms, indicating its wider circulation within African American communities and beyond. In 1926, a song titled “Oh, Lordy Won’t You Come By Here” was published by Madelyn Sheppard, a white songwriter known for composing blues and spirituals in African American dialect. While not identical to “Kumbaya,” its appearance at this time underscores the song’s presence in the cultural landscape.

Musical transcription of “Come By Here” as sung by H. Wylie in 1926. Transcription by Jennifer Cutting. Click to enlarge.

Further evidence comes from the 1931 publication in The Carolina Low Country by the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, featuring a song called “Come by Yuh.” Collected sometime between 1922 and 1931, it shares the refrain “Come By Yuh, Lord, come by yuh” and the verse “somebody need you lord, come by yuh,” reinforcing the evolving form of the “kumbaya kumbaya song.”

In 1936, John Lomax, Gordon’s successor at the Archive, recorded Ethel Best in Florida singing another version of “Come by Here.” Her rendition, with verses like “Well we [down in?] trouble, Lord, come by here” and “Well, it’s somebody needs you lord, come by here,” further demonstrates the song’s variations and widespread presence in the American South.

Re-evaluating Theories of Origin: Gullah Geechee and Beyond

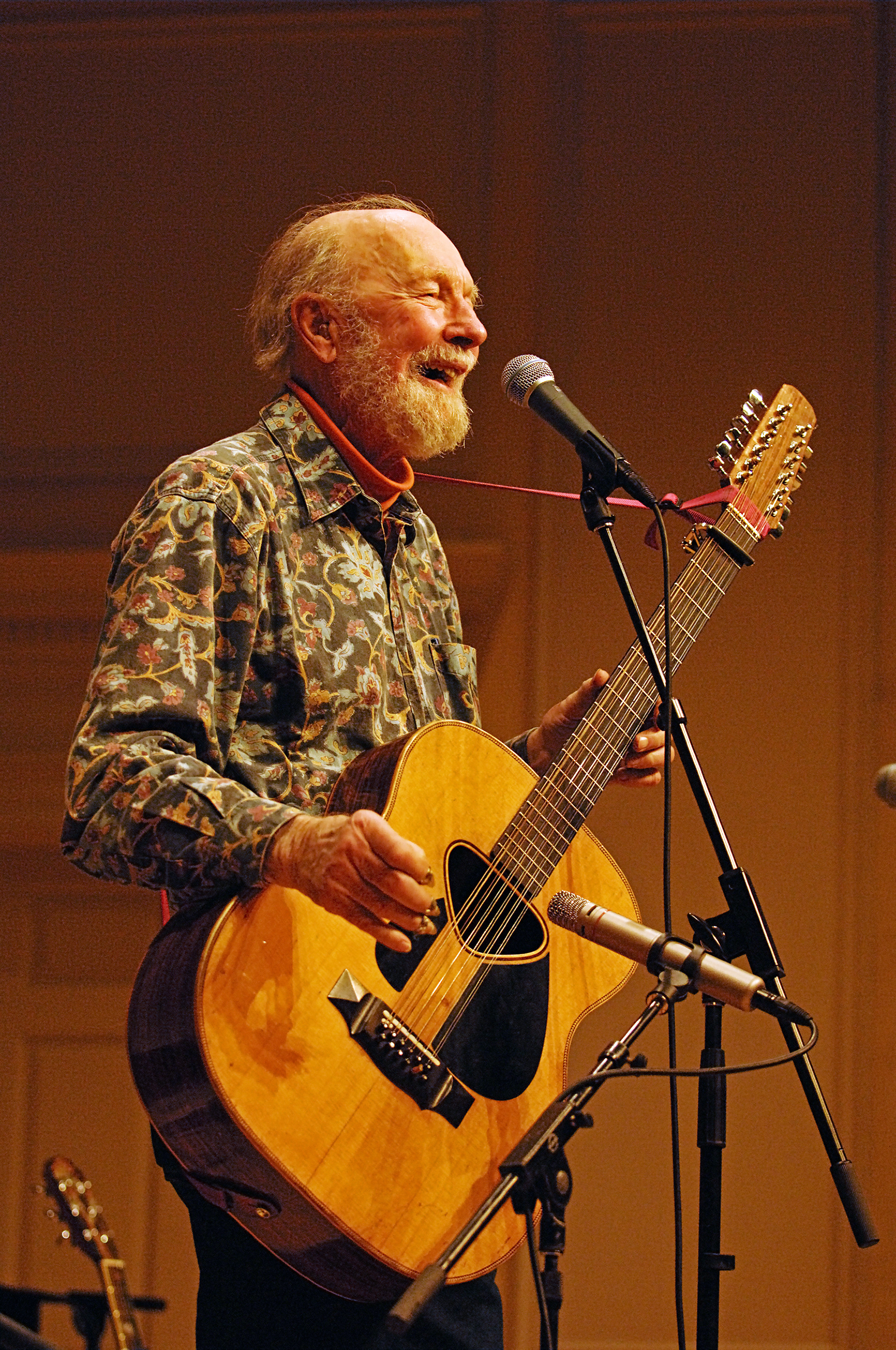

Pete Seeger, instrumental in popularizing “Kumbaya” during the folk revival. Photo by Robert Corwin, March 2007, Library of Congress.

The wealth of early evidence from the American Folklife Center Archive significantly impacts theories surrounding the origin of “kumbaya kumbaya song.” The claim that Marvin Frey composed the song in 1936 becomes increasingly unlikely given the documented versions predating his claim by a decade or more. Frey’s narrative of deriving “Come By Here” from a spoken prayer, not a song, is further weakened by the clear musical and lyrical connections to these earlier renditions.

Similarly, the notion of an African origin for “Kumbaya” is challenged by the archival findings. While the name “Kumbaya” might sound vaguely African, the linguistic analysis and early recordings point strongly towards an American origin within African American English dialects. H. Wylie’s pronunciation of “here” as “yah” in his 1926 recording provides a crucial link to the “Kum Ba Yah” pronunciation that became popularized later.

The theory of a Gullah Geechee origin remains plausible and is supported by the geographical concentration of early recordings in coastal Georgia and South Carolina. However, the 1926 Boyd manuscript from North Carolina suggests the song’s circulation extended beyond the Gullah Geechee region even in its early years. Therefore, while a Gullah Geechee influence is highly probable, “kumbaya kumbaya song” likely emerged from broader African American spiritual traditions in the American South.

“Kumbaya” and the Folk Revival: A Global Journey

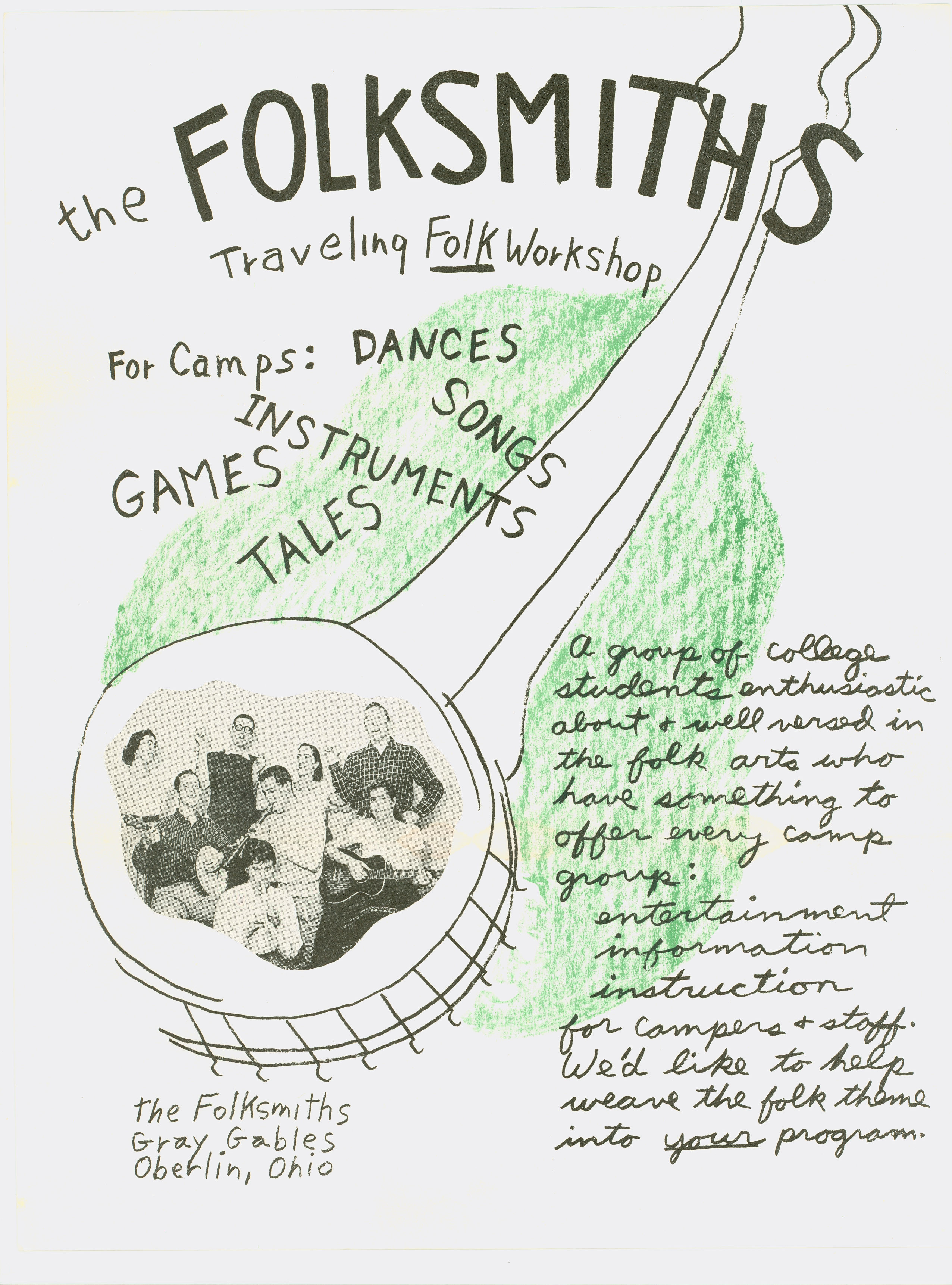

Poster for the Folksmiths, 1957, highlighting their role in popularizing “Kumbaya.” Courtesy of Joe Hickerson.

The journey of “kumbaya kumbaya song” took another significant turn with its adoption into the folk revival movement of the mid-20th century. Lynn and Katherine Rohrbough’s publications played a key role in introducing the song to a wider audience. In 1957, Tony Saletan learned the song from the Rohrboughs and shared it with The Folksmiths, a group from Oberlin College.

The Folksmiths’ tours of summer camps in 1957 proved pivotal in popularizing “Kumbaya” among American youth, solidifying its association with campfires and communal singing. Their 1957 recording, released in 1958, is considered the first published recording of the song in the folk revival style. Pete Seeger’s subsequent recordings in 1958 and 1959 further cemented “Kumbaya” in the folk repertoire and contributed to the standardization of the “Kumbaya” title.

Intriguingly, key figures in the folk revival’s embrace of “Kumbaya” had connections to the American Folklife Center Archive. Pete Seeger himself had been an intern at the Archive in the 1930s and recalled hearing Gordon’s cylinder recording. Joe Hickerson of the Folksmiths later became the Head of the Archive. This connection underscores the Archive’s role not only in preserving the early history of “kumbaya kumbaya song” but also in its later dissemination and transformation into a global folk song.

In conclusion, the history of the “kumbaya kumbaya song” is a rich tapestry woven from African American spiritual traditions, archival discoveries, and its journey through the folk revival. While often simplified and sometimes derided, the song’s origins reveal a profound plea for solace and connection, rooted in the cultural heritage of the American South and preserved for generations to come thanks to resources like the American Folklife Center Archive.