Episode one hundred and fifty-eight of A History of Rock Music in Five Hundred Songs delves into “White Rabbit,” a defining track by Jefferson Airplane that encapsulated the San Francisco Sound and the psychedelic era of the 1960s. This exploration goes beyond the original episode, offering a richer understanding of the song’s origins, cultural impact, and enduring legacy within rock history.

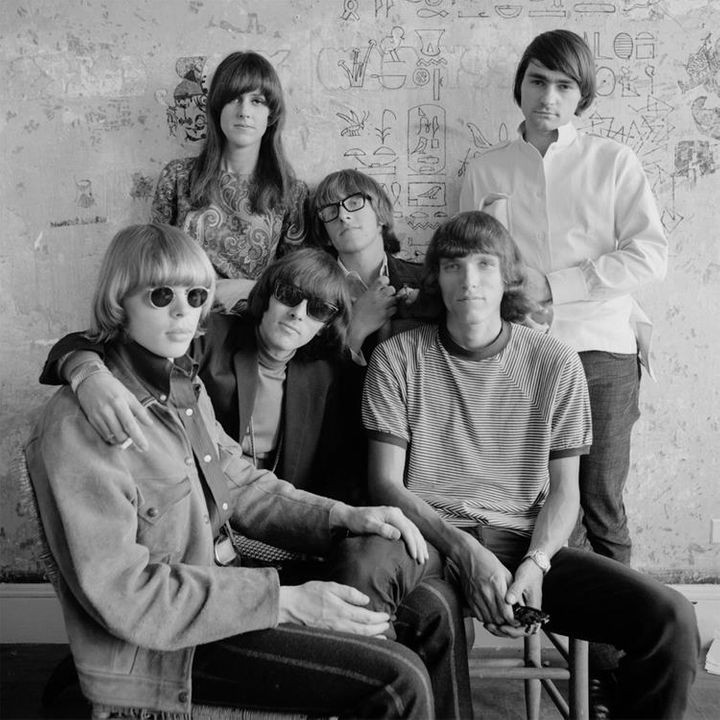

Jefferson Airplane band portrait for White Rabbit song analysis

Jefferson Airplane band portrait for White Rabbit song analysis

From Folk Roots to Psychedelic Flight: The Genesis of Jefferson Airplane

The narrative of Jefferson Airplane, a band synonymous with the San Francisco counterculture, begins with Marty Balin. Balin, seeking a musical path after a brief stint as a Ricky Nelson-esque hopeful, transitioned to folk music. Recognizing the seismic shift brought by the British Invasion, particularly The Beatles, Balin aimed to create a folk-rock ensemble. This ambition led him to Paul Kantner, a like-minded musician with a rebellious spirit, and together they laid the foundation for Jefferson Airplane.

Their initial lineup included bassist Bob Harvey, drummer Jerry Peloquin, and vocalist Signe Toley (later Anderson). Crucially, they sought a distinctive lead guitarist, leading them to Jorma Kaukonen, a blues purist with a deep appreciation for Americana. Kaukonen, initially hesitant about electric rock, was swayed by the sonic possibilities of an Echoplex and the encouragement of Ken Kesey, the famed author and Merry Prankster figurehead.

It was Kaukonen who inadvertently christened the band “Jefferson Airplane,” a name born from a bluesman pseudonym, solidifying their identity as a key player in the burgeoning San Francisco scene. To cultivate this scene, Balin spearheaded the opening of the Matrix Club, providing a vital venue for their rehearsals and early performances.

Marty Balin performing at The Matrix club, the birthplace of Jefferson Airplane

Marty Balin performing at The Matrix club, the birthplace of Jefferson Airplane

Early Days and Lineup Shifts

Managed initially by Matthew Katz, Jefferson Airplane quickly gained local traction, fueled by Katz’s promotional efforts and positive press from San Francisco Chronicle writers Ralph Gleason and John Wasserman. Record labels soon took notice, initiating a period of personnel changes before their major label debut.

Jerry Peloquin’s traditional drumming style clashed with the band’s evolving sound, leading to his replacement by Skip Spence, a guitarist surprisingly turned drummer. Bob Harvey’s double bass initially anchored their sound, but he was eventually replaced by Jack Casady, Kaukonen’s longtime friend, on electric bass. This evolving lineup, marked by internal friction, particularly between Kantner and Casady, journeyed to Los Angeles to audition for record labels.

Signing with RCA and the Departure of Signe Anderson

RCA Records, seeking to tap into the burgeoning rock market, signed Jefferson Airplane after an introduction by Rod McKuen. However, their initial contract with manager Matthew Katz and RCA was fraught with issues. Signe Anderson, displaying rare foresight, initially refused to sign due to concerns about the contract’s terms, though she eventually relented. Jack Casady also signed what he believed was the contract, later discovered to be a forgery.

Their debut album, Jefferson Airplane Takes Off, produced by Tommy Oliver, was commercially unsuccessful outside of San Francisco. Musically, it was a nascent effort, capturing their early sound but lacking the defining edge they would soon achieve. Before significant success arrived, Signe Anderson, pregnant and disillusioned, departed the band.

The Arrival of Grace Slick and the “Surrealistic Pillow” Era

The pivotal moment for Jefferson Airplane arrived with the addition of Grace Slick. Slick, previously the lead singer of The Great Society, was inspired by Jefferson Airplane’s local success and perceived a better path for her musical ambitions. Her joining marked a transformation in the band’s sound and trajectory.

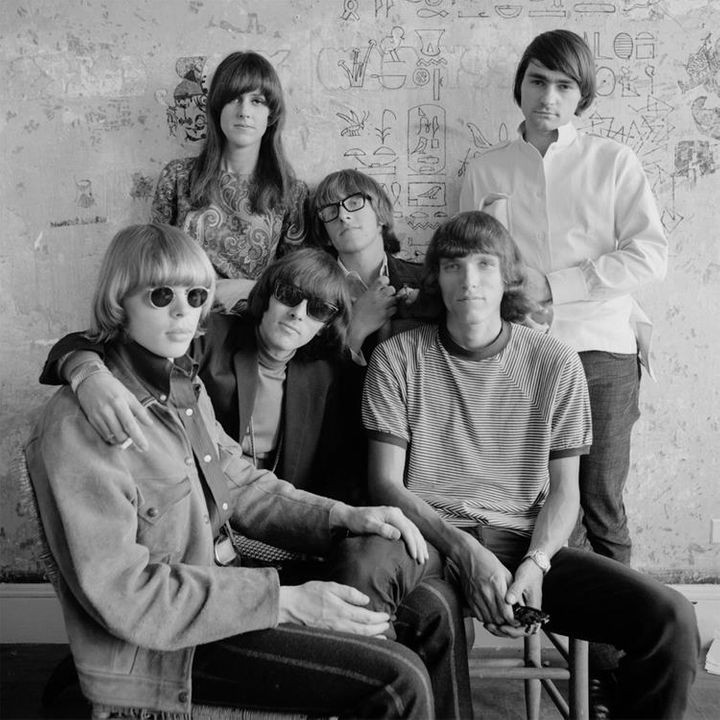

Jefferson Airplane band portrait for White Rabbit song analysis

Jefferson Airplane band portrait for White Rabbit song analysis

With Slick on board and Rick Jarrard as the new producer, alongside engineer Dave Hassinger, Jefferson Airplane recorded Surrealistic Pillow. This album, rumored to have benefited from uncredited contributions by Jerry Garcia, catapulted them to national fame. Crucially, it featured re-recordings of two songs from Grace Slick’s previous band, The Great Society: “Somebody to Love” and “White Rabbit.”

“Somebody to Love,” released as a single, became their breakthrough hit, reaching number five on the charts. This success paved the way for “White Rabbit” to become a cultural phenomenon.

“White Rabbit”: A Psychedelic Trip Through Wonderland

“White Rabbit” is arguably Jefferson Airplane’s most iconic song and a defining anthem of the psychedelic era. Written by Grace Slick, the song’s lyrical inspiration stems directly from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Slick herself explained the connection, highlighting how childhood exposure to fantasy literature, filled with imagery of altered states and fantastical transformations, resonated with the burgeoning psychedelic movement.

The lyrics directly reference characters and events from Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, such as the White Rabbit, the Caterpillar (“hookah-smoking Caterpillar”), the Dormouse, and the Red Queen. The song uses these images as metaphors for the psychedelic experience, inviting listeners to “feed your head” and question reality.

Musically, “White Rabbit” is distinctive for its dramatic crescendo, mirroring the intensifying effects of a psychedelic trip. Slick cited Miles Davis’ Sketches of Spain and, more explicitly, Ravel’s Bolero as musical inspirations, particularly for the song’s building intensity and modal melody reminiscent of Spanish music. The song avoids traditional verse-chorus structure, instead relying on a hypnotic, Spanish-flavored riff that repeats and intensifies throughout, driven by Jack Casady’s bassline and Spencer Dryden’s drumming.

Released as a single in June 1967, “White Rabbit” quickly climbed the charts, peaking at number eight. Despite its overt drug references – “pills,” “mushrooms” – RCA surprisingly allowed its release, perhaps recognizing its cultural resonance. The song’s success solidified Surrealistic Pillow‘s commercial triumph and cemented Jefferson Airplane’s place at the forefront of the San Francisco Sound.

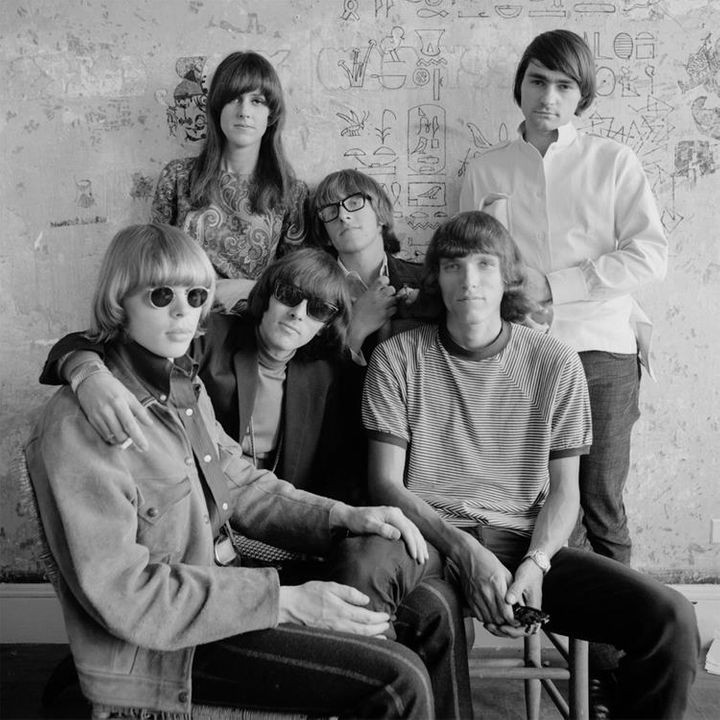

Jefferson Airplane band portrait for White Rabbit song analysis

Jefferson Airplane band portrait for White Rabbit song analysis

Cultural Impact and Enduring Legacy

“White Rabbit” transcended mere chart success, becoming a cultural touchstone for the 1960s counterculture. Its association with psychedelic experiences, coupled with its literary allusions, resonated deeply with a generation questioning societal norms and exploring altered states of consciousness. The song’s brevity, clocking in at under two and a half minutes, made it a concise and potent statement, perfectly suited for radio airplay and instant impact.

While Jefferson Airplane, as a band, may not have exerted a vast musical influence on subsequent artists in terms of direct imitation, their cultural influence is undeniable. They helped define the aesthetic, political, and behavioral norms of rock musicians for decades to come. The San Francisco scene they spearheaded, epitomized by songs like “White Rabbit,” laid the groundwork for Woodstock, Rolling Stone magazine, and the very concept of the rock star.

Grace Slick, with her powerful vocals and stage presence, became a feminist icon, inspiring a generation of women in rock music. “White Rabbit,” even decades later, remains evocative of the Summer of Love and the spirit of 1967, demonstrating the enduring power of a song that captured a specific moment in time and yet continues to resonate. Slick herself humorously noted that she still largely lives off the royalties from “White Rabbit,” a testament to its lasting commercial and cultural value.

Beyond “White Rabbit”: Jefferson Airplane’s Trajectory and Fragmentation

Following the success of Surrealistic Pillow and “White Rabbit,” Jefferson Airplane continued to navigate the complexities of fame and internal band dynamics. Albums like After Bathing at Baxter’s and Crown of Creation showcased their evolving psychedelic sound but achieved less commercial success than their breakthrough album.

Internal tensions, fueled by ego clashes, differing musical directions (instrumental jams vs. pop sensibilities), and substance abuse, began to fragment the band. Marty Balin, feeling increasingly marginalized, eventually left. Spencer Dryden also departed, further altering their lineup.

Despite these challenges, Jefferson Airplane persisted, morphing into different iterations, including Hot Tuna (Kaukonen and Casady’s blues-focused project) and Jefferson Starship (Kantner and Slick’s more commercially oriented venture). Jefferson Starship, ironically, achieved greater mainstream success in the 1970s and 80s with a pop-rock sound far removed from Jefferson Airplane’s psychedelic origins.

A Lasting Echo of the Summer of Love

Jefferson Airplane’s active period in the spotlight was relatively brief, primarily centered around the late 1960s. However, “White Rabbit” and their association with the Summer of Love ensured their place in rock history. The song remains a powerful symbol of a transformative era, forever linked to psychedelic exploration and the cultural shifts of the 1960s. While the band itself fractured and evolved, “White Rabbit” endures as a timeless anthem, capturing the spirit of a generation and the magic of a fleeting moment in music history.