Many find themselves drawn to Japanese culture through various avenues – be it exploring intricate Japanese recipes or immersing in the melodies of Japanese music. For some, this appreciation deepens over time, much like a fine wine maturing in its cellar. There’s a growing recognition of the importance of representation, especially for hyphenated identities, and a hope for genuine storytelling that illuminates history. Think of moments in shows like “Never Have I Ever” that touch upon the complexities of internment – these are vital steps in cultural understanding.

While Japanese culture enjoys considerable visibility, a particular song within popular culture remains shrouded in misunderstanding: “Ue o Muite Arukō,” globally recognized as “Sukiyaki.”

Kyu Sakamoto’s rendition of “Ue o Muite Arukō,” penned by Rokusuke Ei and Hachidai Nakamura, resonated deeply with audiences, achieving instant hit status in Japan before captivating Europe and North America. However, the contexts surrounding the song’s ascent to the top of global charts varied significantly across these regions.

In 1960s Japan, the ratification of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty ignited widespread discontent among Japanese citizens advocating for the removal of American military presence. This treaty sparked the massive Anpo protests. It was in the aftermath of these demonstrations that Ei, witnessing the potential disillusionment of young people facing governmental resistance, crafted the song.

The lyrics, when detached from Sakamoto’s upbeat vocal delivery, reveal a poignant melancholy. He may have been smiling for the cameras, but beneath the surface lay a profound sadness.

Consider this translation from Kansai Culture:

| Japanese | English |

|---|---|

| Ue o muite arukouNamida ga koborenai you niOmoidasu haru no hiHitoribotchi no yoruUe o muite arukouNijinda hoshi o kazoeteOmoidasu natsu no hiHitoribotchi no yoru Shiawase wa kumo no ue niShiawase wa sora no ue ni Ue o muite arukouNamida ga koborenai you niNakinagara arukuHitoribotchi no yoru [Whistling] Omoidasu aki no hiHitoribotchi no yoru Kanashimi wa hoshi no kage niKanashimi wa tsuki no kage ni Ue o muite arukouNamida ga koborenai you niNakinagara arukuHitoribochi no yoruHitoribochi no yoru | I look up as I walkSo the tear won’t fallRemembering those spring daysBut I am all alone tonightI look up as I walkCounting the stars with tearful eyesRemembering those summer daysBut I am all alone tonight Happiness lies up above the cloudsHappiness lies up in the sky I look up as I walkSo that the tears won’t fallThough the tears well up as I walkFor tonight I am all alone [Whistling] Remembering those autumn daysBut I am all alone tonight Sadness lies in the shadow of the starsSadness lurks in the shadow of the moon I look up as I walkSo that the tears won’t fallThough the tears well up as I walkBut I am all alone tonight.But I am all alone tonight. |

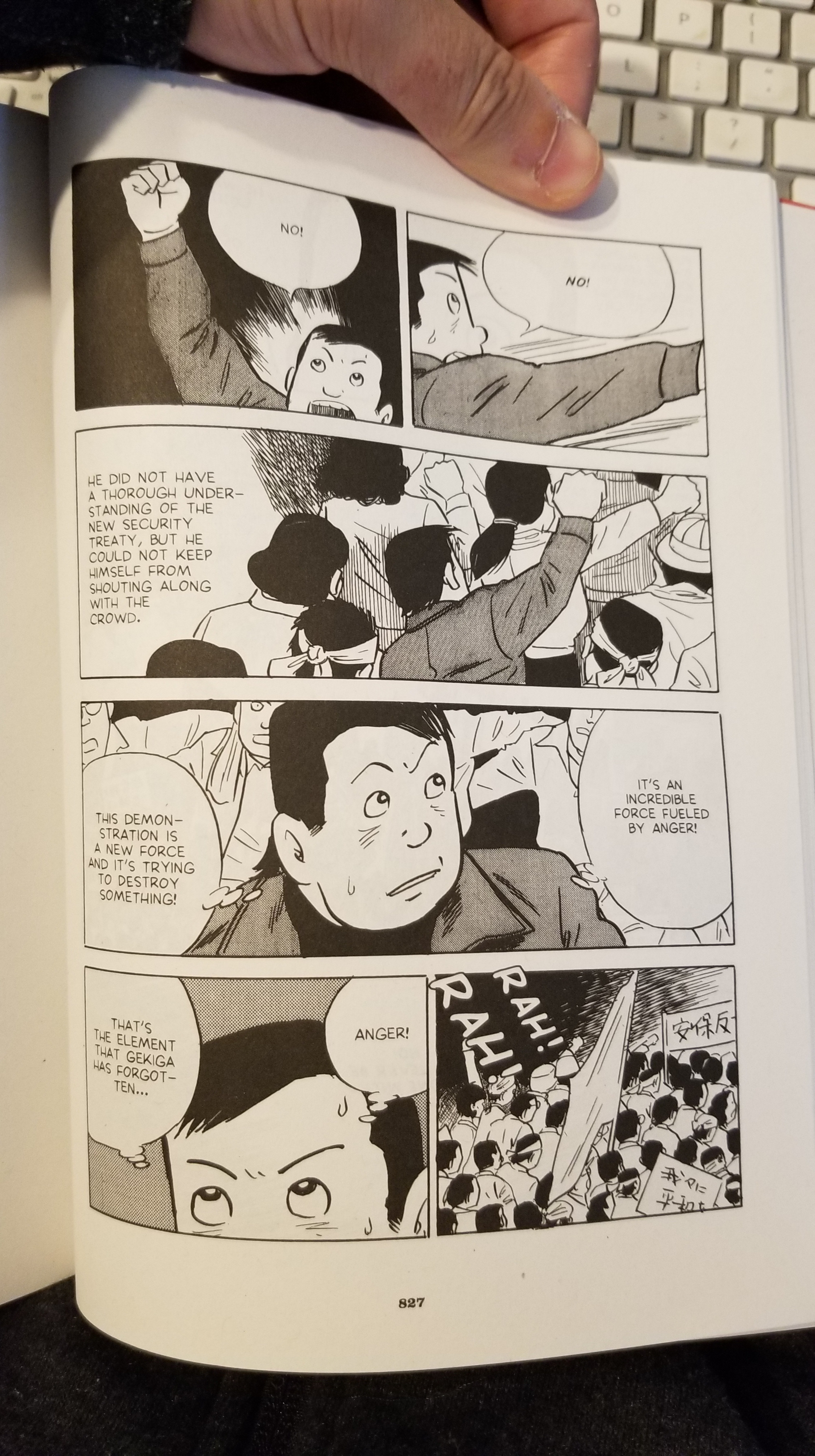

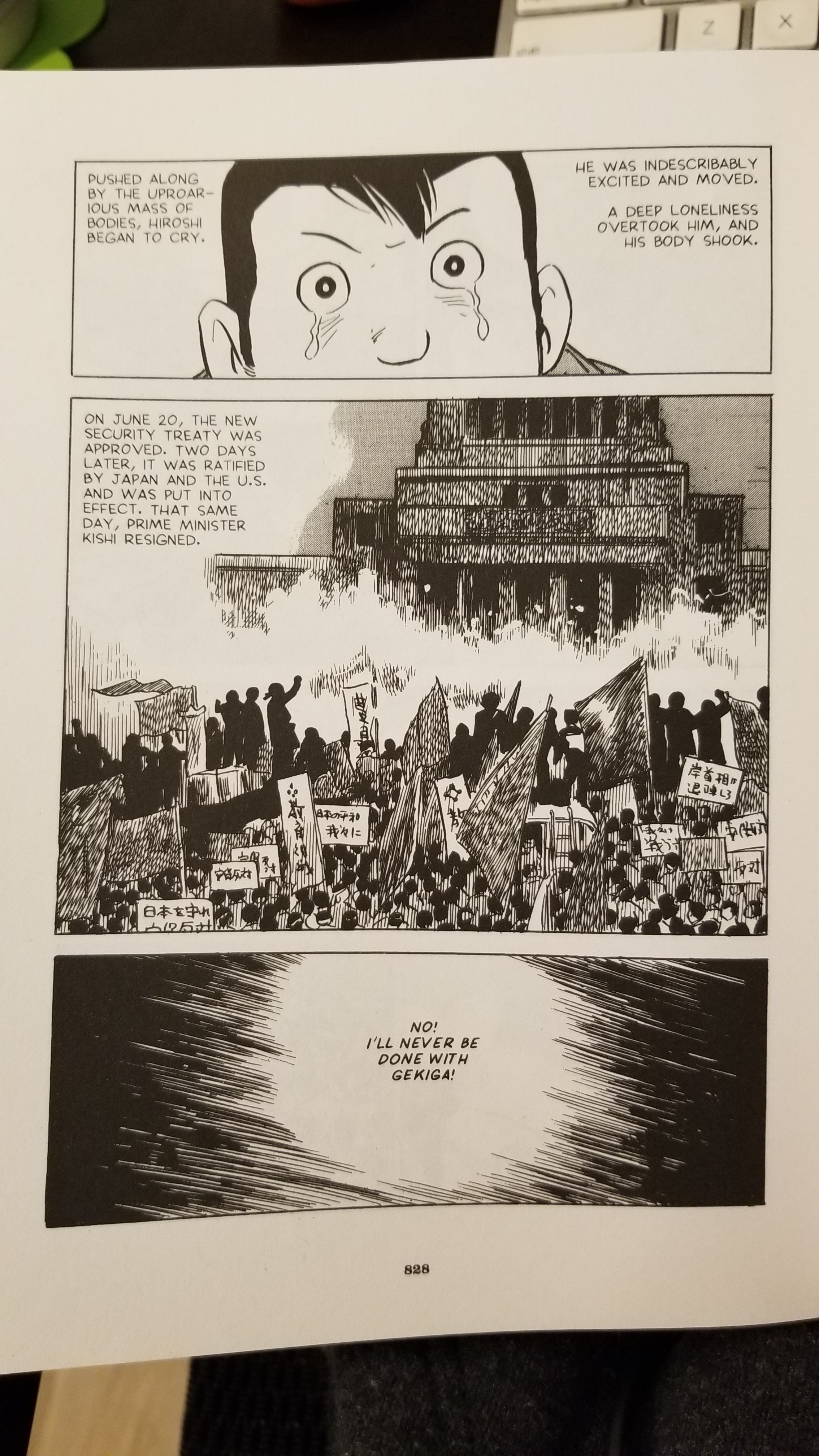

Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s autobiographical manga “A Drifting Life” offers a compelling visual representation of the Anpo protests. In one sequence, Tatsumi finds himself amidst the throng of protestors.

Anpo Protests Depicted in Yoshihiro Tatsumi's "A Drifting Life"

Anpo Protests Depicted in Yoshihiro Tatsumi's "A Drifting Life"

Manga panel showing crowds during Anpo Protests

Manga panel showing crowds during Anpo Protests

Manga close up of a character looking up with tears in his eyes during a protest

Manga close up of a character looking up with tears in his eyes during a protest

Surrounded by a sea of people, he reflects on the emotional depth of his Gekiga style of manga, then gazes skyward, tears brimming – an unmistakable echo of the song’s sentiment. He is profoundly moved by the collective action yet feels acutely isolated.

It’s this intricate tapestry of emotions that the song endeavors to convey through its lyrics, subtly masked as a ballad of lost love. “Ue o Muite Arukō” is, at its core, a protest song, a dimension often overlooked in its popular culture portrayals.

Overseas Popularity and the “Sukiyaki” Misnomer

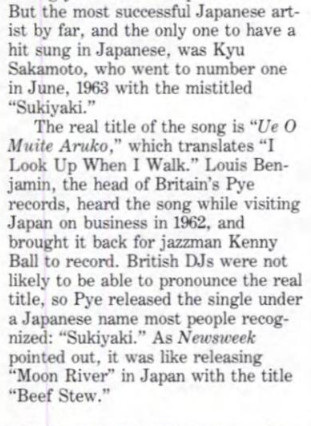

In 1962, Louis Benjamin of U.K.-based Pye Records made the decision to reissue the song under the title “Sukiyaki.” The rationale? Simplicity for English speakers. Believe it or not, the change was attributed to the perceived difficulty in pronouncing the original Japanese title.

While the pronunciation argument holds a degree of validity – even Google Translate stumbles over “Ue o Muite Arukō” – the chosen title remains, to put it mildly, peculiar.

Google Search Result Mockup Highlighting the Absurdity of Renaming "Ue o Muite Arukō" to "Sukiyaki"

Google Search Result Mockup Highlighting the Absurdity of Renaming "Ue o Muite Arukō" to "Sukiyaki"

Fred Bronson’s “The Billboard Book of Number One Hits” recounts a Newsweek analogy that likened the renaming to rebranding “Moon River” as “Beef Stew” in Japan.

Despite the arguably nonsensical title, the song achieved widespread release in the United States in 1963, achieving remarkable success. Numerous artists, including A Taste of Honey, created their own renditions, further cementing the song’s popularity, yet often straying from its original intent.

A Taste of Honey’s version, for instance, leaned heavily into love-song themes. But back in the 1980s, outside of Japanese American communities, familiarity with the Japanese language and culture was limited. Consequently, many interpretations opted for readily accessible love-song narratives, overshadowing the haunting essence of the original.

“Sukiyaki Song” in Popular Culture Today: Lost in Translation

One recent example of the song’s use appears in the 2020 series “Dash & Lily.” In a scene, Dash is shown preparing Daifuku Mochi alongside a group of older Japanese women. “Sukiyaki” plays softly in the background as he discusses his burgeoning connection with the enigmatic Lily through their shared red notebook.

Again, the song’s context is romantic – love and connection – diverging from its themes of melancholy and reflection on the past. It’s noteworthy that in the source book, Lily’s character was not Japanese American. While the show deserves credit for casting Japanese actors in family roles, the song choice still reinforces the diluted, romanticized interpretation.

Then there’s the “Mad Men” example. Some suggest the song’s inclusion is linked to a character’s father dying in a plane crash, drawing a parallel to Kyu Sakamoto’s tragic death in the Japan Air Lines Flight 123 crash.

However, it’s more likely the writers simply sought a recognizable Japanese song for a Japanese restaurant scene. The episode is set in 1962, yet the song’s US breakthrough was a year later – a minor anachronism. While Don Draper embodies a certain forlornness, the scene is marred by the stereotypical, sexualized portrayal of an Asian waitress, dressed in a pastiche of Asian fashion clichés. This reinforces a reductive, Orientalist view rather than adding meaningful cultural context.

Rediscovering the Protest Heart of “Sukiyaki”

Perhaps this exploration has wandered somewhat, but the core message remains: “Sukiyaki” is profoundly disconnected from the savory Japanese dish of the same name. It is fundamentally a protest song, born from the anguish and frustration of witnessing societal disappointment and governmental actions perceived as unjust. Understanding this original intent allows for a richer, more nuanced appreciation of this globally beloved song.