Pink Floyd stands as a monumental force in rock history, renowned for their innovative soundscapes, philosophical lyrics, and groundbreaking album concepts. Emerging from the vibrant UK underground scene of the late 1960s, their early work, spearheaded by the enigmatic Syd Barrett, laid the foundation for psychedelic rock and beyond. This article delves into the formative years of Pink Floyd’s songbook, exploring the tracks that defined their initial psychedelic phase and the genius, and eventual tragedy, of their founding member.

A jukebox, with the words Payoff Song, A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

A jukebox, with the words Payoff Song, A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Episode 157 of the celebrated podcast A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs meticulously examines “See Emily Play,” a quintessential track from Pink Floyd’s early catalog. This song not only encapsulates the spirit of the burgeoning UK underground but also highlights the pivotal role of Roger “Syd” Barrett in shaping the band’s initial artistic direction. Barrett’s unique approach to songwriting, heavily influenced by children’s literature, avant-garde art, and the burgeoning psychedelic culture, set Pink Floyd apart from their contemporaries.

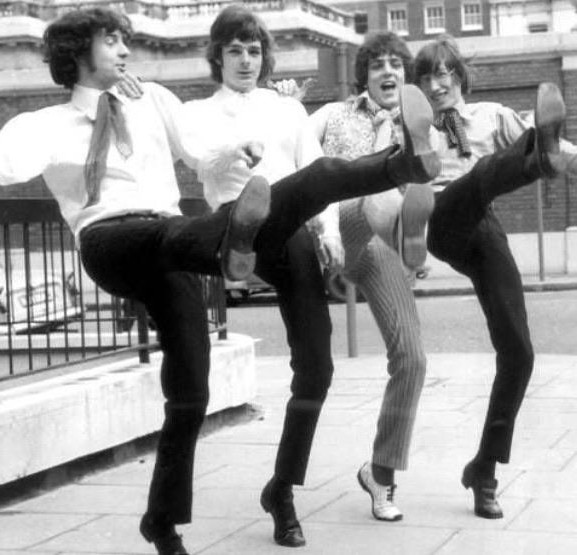

Pink Floyd performing in 1967, known for their energetic stage presence with synchronized high kicks

Pink Floyd performing in 1967, known for their energetic stage presence with synchronized high kicks

The Cambridge Roots and Syd Barrett’s Artistic Genesis

Roger Barrett, born in Cambridge in 1946, was the creative nucleus around which the early Pink Floyd sound coalesced. Cambridge, a city steeped in intellectual tradition, fostered a unique environment for artistic eccentricity. Barrett’s upbringing, within a family that valued both intellectual pursuits and artistic expression, played a crucial role in shaping his creative sensibilities. His father, a pathologist with a passion for watercolor painting and music, and his community-active mother, provided a stimulating backdrop for young Roger’s burgeoning interests in art and music.

His childhood passions were nurtured by the whimsical world of children’s literature. Books like The Wind in the Willows, particularly the chapter “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn,” Alice in Wonderland, and The Little Grey Men deeply resonated with him, sparking his imagination and later influencing his songwriting. These pastoral and fantastical narratives would become recurring motifs in his lyrics, lending Pink Floyd’s early songs a distinctive fairytale-like quality.

Barrett’s musical journey began with a ukulele at age eleven, progressing to guitar by his teenage years. Initially drawn to popular music of the time, including artists like Chubby Checker and Joe Brown, Barrett’s tastes evolved, leaning towards the more unconventional and quirky aspects of the music scene.

[Excerpt: Joe Brown, “I’m Henry VIII I Am”]

Cambridge’s distinctive atmosphere, characterized by a blend of intellectualism and eccentricity, further molded Barrett’s artistic persona. The city’s university environment attracted individuals who thrived in unconventional settings, often fostering a spirit of intellectual rebellion and unconventional thinking. This backdrop likely contributed to Barrett’s unique artistic vision and his simultaneous desire to both embrace and subvert societal expectations.

Initially, art seemed to be Barrett’s primary creative outlet. His talent as a painter, particularly his mastery of color, was widely recognized. However, his growing fascination with R&B music, especially the raw energy of Bo Diddley, began to shift his focus.

[Excerpt: Bo Diddley, “Who Do You Love?”]

He spent countless hours with his friend David Gilmour, a more experienced guitarist, immersing himself in blues riffs and honing his musical skills. It was during this period that Roger Barrett became known as “Syd,” a nickname with origins shrouded in local Cambridge lore, adding to his mystique.

From The Tea Set to The Pink Floyd Sound: Forging a Band

In 1962, Syd Barrett joined Geoff Mott and the Mottoes, his first foray into band life. While short-lived, this experience provided early stage experience. Later, connections with musicians like Tony Sainty and Clive Welham, who formed Jokers Wild with Dave Gilmour, kept Barrett connected to the evolving Cambridge music scene. Though some accounts suggest Roger Waters’ involvement with the Mottoes, it’s more definitively documented that Barrett knew Waters, and their paths converged when Barrett moved to London to attend Camberwell Art College in 1964, sharing a house with Waters.

This London house became a hub for musical experimentation. Previous tenants, Nick Mason and Richard Wright, along with Waters, had already formed a band with rotating names like Sigma 6, The Megadeaths, and The Tea Set. When Barrett joined, the “Tea Set” name was prevalent, and the lineup included Waters, Mason, Wright, singer Chris Dennis, and guitarist Rado Klose. Klose, a skilled jazz guitarist, was the most musically proficient member, while the others were still developing their instrumental skills.

By this time, Barrett’s musical horizons were expanding, encompassing folk music and artists like Bob Dylan. However, the blues remained a central influence. As The Tea Set gravitated towards a blues-oriented sound, Barrett’s arrival marked a turning point. He proposed a new name, inspired by two obscure blues musicians he’d seen listed on a record cover – Pink Anderson and Floyd Council.

[Excerpt: Pink Anderson, “Boll Weevil”]

[Excerpt: Floyd Council, “Runaway Man Blues”]

Combining these names, “The Pink Floyd Sound” was born, though they occasionally still performed as The Tea Set. This new moniker, a nod to American blues roots, ironically heralded a band that would soon pioneer a distinctly British psychedelic sound.

Early performances included auditions for shows like Ready Steady Go! and support slots for bands like The Tridents.

[Excerpt: The Tridents, “Tiger in Your Tank”]

The Tridents’ guitarist, Jeff Beck, particularly impressed Barrett with his innovative use of feedback, a technique that would later become a hallmark of Pink Floyd’s sound. Initially, The Pink Floyd Sound primarily performed covers, but they were also developing original material, showcased in early demo sessions. These demos included Roger Waters’ humorous track “Walk With Me Sydney” and four songs penned by Barrett, including the Bo Diddley-esque “Double-O Bo” and the more nuanced “Butterfly”.

[Excerpt: The Tea Set, “Walk With Me Sydney”]

[Excerpt: The Tea Set, “Butterfly”]

Barrett’s early vocal performances were marked by insecurity, as evidenced in letters to his girlfriend. However, his distinctive songwriting was already emerging as the band’s defining characteristic.

Psychedelic Explorations and the Birth of a Unique Sound

The summer of 1965 brought two pivotal events for Barrett and Pink Floyd. Barrett’s experimentation with LSD marked a profound shift in his creative perspective. While the other band members were less inclined to regular drug use, Barrett’s consistent psychedelic experiences deeply influenced his songwriting and artistic direction, pushing Pink Floyd towards uncharted sonic territories.

The departure of Rado Klose, the band’s most technically proficient musician, was the second significant event. Klose’s jazz-oriented preferences differed from the band’s evolving direction, and his departure forced Pink Floyd to rethink their musical approach. Instrumental proficiency was no longer the primary focus; instead, they began to prioritize sonic experimentation and innovative ideas.

Echo became a central element in their sound. Primitive echo devices were used to process Barrett’s guitar and Wright’s keyboards, creating novel sonic textures and spatial effects previously unheard in live performances. While their setlists still included blues covers, the band was actively seeking a unique musical identity.

An unexpected source of inspiration came from the London Free School, an organization promoting counter-cultural ideas and community education. Associated with the Free School was the avant-garde improvisational music group AMM.

[Excerpt: AMM, “What Is There In Uselesness To Cause You Distress?”]

AMM’s guitarist, Keith Rowe’s technique-free approach, focused on pure sound and texture rather than conventional melody and harmony, deeply resonated with Barrett’s painterly sensibilities and encouraged him to explore similar sonic landscapes with his guitar.

AMM’s 1966 debut album on DNA Records, a label founded by London Free School members, further solidified this avant-garde influence. Peter Jenner, one of the DNA founders, recognized the label’s financial limitations with purely experimental music and realized the need for a “pop band” to achieve sustainability. This led Jenner and Andrew King to become pop managers, discovering The Pink Floyd Sound at a Spontaneous Underground event.

Impressed by their unique sound and stage presence, Jenner and King signed Pink Floyd, recognizing Barrett as the band’s creative core. Jenner later described the band’s early dynamic: “Four not terribly competent musicians who managed between them to create something that was extraordinary. Syd was the main creative drive behind the band.”

During the summer break of 1966, Jenner encouraged Barrett to focus on original songwriting, urging the band to move beyond blues covers. Barrett embraced this challenge, and upon reconvening after the summer, Pink Floyd began to solidify their original psychedelic direction.

UFO Club and the Dawn of the Underground

Pink Floyd’s association with the London Free School led to benefit performances and, ultimately, the birth of the UFO Club, a pivotal venue for the UK underground scene. Jenner and King developed innovative light shows that became integral to Pink Floyd’s performances. Working in shadows, with kaleidoscopic projections, they created a detached, immersive experience for the audience, distinguishing themselves from conventional spotlight-focused bands.

“Interstellar Overdrive” became a centerpiece of their sets, a lengthy instrumental piece that showcased their psychedelic explorations. This track was among their first professional recordings, captured for the soundtrack of the film Tonite Let’s All Make Love in London.

The inspiration for “Interstellar Overdrive”‘s iconic riff is debated. Possible sources include Love’s version of “My Little Red Book” and Ron Grainer’s theme for the sitcom Steptoe and Son.

[Excerpt: Love, “My Little Red Book”]

[Excerpt: Ron Grainer, “Old Ned”]

Regardless of the precise inspiration, the riff embodies the eclectic influences shaping Pink Floyd’s sound – blending pop sensibilities with experimental and distinctly British undertones.

[Excerpt: The Pink Floyd, “Interstellar Overdrive”]

Alongside extended instrumental pieces like “Interstellar Overdrive,” Pink Floyd also developed whimsical, story-based songs, drawing inspiration from everyday life and children’s literature. “Candy and a Currant Bun,” the B-side to their first single, was built upon the riff of Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightnin’”.

[Excerpt: Howlin’ Wolf, “Smokestack Lightnin'”]

Originally titled “Let’s Roll Another One,” with lyrics referencing cannabis, the song was hastily rewritten to remove drug references, though subtle suggestive elements remained.

[Excerpt: The Pink Floyd, “Candy and a Currant Bun”]

The A-side, “Arnold Layne,” was inspired by a real-life character – a thief who stole women’s underwear from washing lines, imagined by Barrett as a cross-dresser.

[Excerpt: The Pink Floyd, “Arnold Layne”]

Chart Success and the Transition to Professionalism

After recording “Arnold Layne” and “Candy and a Currant Bun” with Joe Boyd, a bidding war ensued for their release. EMI ultimately signed Pink Floyd, just as the News of the World published articles linking pop stars to drug use, including Pink Floyd. EMI downplayed the psychedelic association in a press release, emphasizing that “The Pink Floyd are not trying to create hallucinatory effects in their audience.”

Signing with EMI marked Pink Floyd’s transition to full-time professionals. “Arnold Layne” reached the UK Top 20 despite a ban from pirate radio station Radio London due to its suggestive themes. However, EMI replaced Joe Boyd with in-house producer Norman Smith, known for his work with The Beatles.

Norman Smith’s production approach aimed for a more structured and commercially viable sound, sometimes curtailing Pink Floyd’s experimental tendencies. This approach proved controversial among some fans but was seen by others, like Peter Jenner, as beneficial for the band’s development.

Pink Floyd began recording their debut album, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn, in studio three at Abbey Road, while The Beatles were completing Sgt Pepper in studio two. The album title, taken from The Wind in the Willows, reflected the whimsical and literary influences on Barrett’s songwriting. Apart from instrumental pieces, the album consisted of short, whimsical songs infused with imagery from Victorian and Edwardian children’s books, a defining characteristic of the British psychedelic scene.

Piper at the Gates of Dawn: A Psychedelic Fairytale

The British psychedelic scene, while sharing counter-cultural roots with its American counterpart, differed significantly in its musical and lyrical themes. While American psychedelic music often reflected anti-war sentiments and blues influences, British psychedelia frequently drew inspiration from pre-war popular song, experimental art music, and children’s literature, evoking a nostalgic, idealized past.

The Beatles’ contemporary work, including “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane,” exemplified this trend, drawing on childhood memories and Victorian imagery. Barrett’s songwriting for Piper at the Gates of Dawn similarly tapped into this vein.

“The Gnome” was inspired by The Little Grey Men by BB (Denys Watkins-Pitchford), capturing the book’s whimsical reverence for nature and fantastical creatures.

[Excerpt: The Pink Floyd, “The Gnome”]

Hilaire Belloc, a prominent early 20th-century writer of children’s cautionary tales, was another significant influence. “Matilda Mother” initially used lyrics directly from Belloc’s Cautionary Tales for Children.

[Excerpt: The Pink Floyd, “Matilda Mother (early version)”]

However, Belloc’s estate denied permission to use his poems, forcing Barrett to rewrite the lyrics for the final version, retaining the fairytale essence but crafting original verses. Other lyrical inspirations included the I Ching, used for “Chapter 24,” mirroring John Lennon’s use of mystical texts.

During the recording of Piper at the Gates of Dawn, Pink Floyd continued to perform live, often to unenthusiastic mainstream audiences at venues like Top Rank Ballrooms. However, they also made significant appearances at events like the 14-Hour Technicolor Dream, a pivotal moment for the UK counterculture, and “Games for May,” where they premiered “See Emily Play.”

“See Emily Play”: Childhood Whimsy and Darker Undertones

“See Emily Play,” Pink Floyd’s second single, was inspired by Emily Young, a young attendee of the London Free School, and Anjelica Huston. Emily’s youthful naiveté and tendency to adopt traits from others inspired the song’s opening lines: “Emily tries, but misunderstands/She’s often inclined to borrow somebody’s dream til tomorrow.”

[Excerpt: The Pink Floyd, “See Emily Play”]

The song evokes a sense of childhood whimsy, but also carries darker undertones, particularly in the final verse, where Emily “floats down a river forever,” conjuring images of Ophelia and the Lady of Shalott, figures of tragic beauty and premature demise. The woods mentioned in the lyrics are said to be woods near Cambridge where Barrett and Roger Waters played as children, adding a personal, nostalgic layer to the song.

“See Emily Play,” initially seven minutes long, was edited down to single length and became Pink Floyd’s biggest hit, reaching the Top 10. This success, however, coincided with the beginning of Syd Barrett’s increasingly erratic behavior and mental decline.

The Fragile Genius: Syd Barrett’s Descent

The period following “See Emily Play”‘s success marked a turning point for Syd Barrett. Two contrasting narratives exist regarding his subsequent decline. One portrays a complete mental breakdown exacerbated by drug use, rendering him unable to function normally. The other suggests a more nuanced picture: Barrett as neurodivergent, overwhelmed by fame and commercial pressures, intentionally sabotaging his pop star persona to reclaim a private life.

Regardless of the specific cause, a profound change in Barrett was evident by the summer of 1967. Joe Boyd noted a stark absence of light in Barrett’s eyes during a meeting after a few weeks apart. During Top of the Pops performances for “See Emily Play,” Barrett became increasingly detached, eventually ceasing to mime altogether. A scheduled BBC Saturday Club session was abandoned when Barrett walked out.

Interestingly, Barrett’s ability to perform seemed context-dependent. He struggled with mainstream pop shows but delivered coherent performances for John Peel’s Perfumed Garden, aimed at Pink Floyd’s underground audience. In late July 1967, Pink Floyd cancelled performances citing Barrett’s “nervous exhaustion.”

Despite these challenges, the band returned to the studio in August, recording Barrett’s “Scream Thy Last Scream,” with Nick Mason on vocals.

[Excerpt: Pink Floyd, “Scream Thy Last Scream”]

This track, deemed too unconventional, was shelved for decades. Instead, they released “Apples and Oranges,” their last single with Barrett.

[Excerpt: Pink Floyd, “Apples and Oranges”]

Pink Floyd’s US tour in November 1967 further highlighted Barrett’s deteriorating state. Legends of catatonic performances on shows like American Bandstand and The Pat Boone Show circulated, though footage reveals a less extreme picture, with Barrett appearing relatively composed, if somewhat detached. However, during live gigs, Barrett’s increasingly erratic behavior, such as detuning his guitar or playing a single note throughout entire songs, became more pronounced.

These actions can be interpreted both as symptoms of mental distress and as deliberate artistic sabotage – a rejection of pop stardom in favor of avant-garde expression. The rest of Pink Floyd, more commercially ambitious than Barrett, faced a growing conflict.

The US tour was cut short, followed by a UK tour with Jimi Hendrix Experience and others. Work on their second album, A Saucerful of Secrets, began, but Barrett’s contributions diminished. He wrote and sang only one song on the album and appeared on just two other tracks. His last song for the band, “Have You Got It Yet?”, was a practical joke, constantly changing to frustrate the other members’ attempts to learn it.

David Gilmour, Barrett’s Cambridge friend, was brought in as a fifth member to stabilize live performances. After a few five-man shows, Pink Floyd simply stopped picking up Barrett for gigs, effectively excluding him from the band without formal announcement. Eventually, Barrett’s departure was officially declared. Managers Jenner and King stayed with Barrett, believing in his solo potential, while Pink Floyd continued with new management, embarking on their own legendary trajectory.

Solo Ventures and a Life Apart

Jenner initially produced Barrett’s early solo recordings in mid-1968, but progress was slow and fragmented. Tracks from these sessions, including an early version of “Golden Hair,” were eventually released.

[Excerpt: Syd Barrett, “Golden Hair (first version)”]

Eleven months later, Barrett resumed solo work with producer Malcolm Jones, starting sessions for his debut solo album, The Madcap Laughs. Jones’ production approach, focusing on polished recordings, was later abandoned in favor of a more raw, “audio verite” style when Gilmour and Waters took over production duties.

This change in production, including studio chatter and false starts, is debated. Jones felt it presented Barrett negatively, while Gilmour and Waters aimed to provide context for the album’s unconventional nature. The Madcap Laughs became a patchwork of sessions, ranging from solo acoustic tracks to fully backed songs featuring Soft Machine.

Despite the production controversies, The Madcap Laughs contains moments of brilliance, albeit intertwined with a palpable sense of fragility and mental distress. Tracks like “Dark Globe” exemplify this duality, showcasing Barrett’s unique artistic vision alongside a haunting vulnerability.

[Excerpt: Syd Barrett, “Dark Globe”]

The Madcap Laughs was successful enough to warrant a follow-up, Barrett, produced by Gilmour and Wright. Recorded more quickly, Barrett is considered more consistent but less compelling than its predecessor, lacking some of the raw, intriguing material of The Madcap Laughs.

[Excerpt: Syd Barrett, “Effervescing Elephant”]

Barrett’s solo career was short-lived. His only solo concert, with the band from Barrett, lasted just four songs. He briefly formed a band “Stars” in Cambridge in the early 1970s but quickly lost interest. A final recording attempt in 1974 with Peter Jenner yielded unreleased tracks, suggesting a further decline in creative output.

A resurgence of interest in Barrett emerged in the mid-1970s, spurred by David Bowie’s cover of “See Emily Play” on Pin-Ups and Nick Kent’s profile, “The Cracked Ballad of Syd Barrett.”

[Excerpt: David Bowie, “See Emily Play”]

Barrett briefly visited Pink Floyd in studio in 1975 during the recording of Wish You Were Here, a poignant, almost mythical encounter where his bandmates initially failed to recognize the changed Barrett. This was their last encounter, except for a chance meeting between Barrett and Roger Waters in Harrods years later, which ended with Barrett fleeing.

For the next three decades, Syd Barrett retreated from public life. His family maintained that while he was private and preferred solitude, he was not a recluse, engaging in daily routines and local interactions. He reportedly disliked the “Syd” persona and preferred to be called Roger. Financially secure due to royalties from Pink Floyd compilations, Barrett spent his time painting, destroying the originals after photographing them.

Roger Keith Barrett died in 2006. His funeral featured classical music by Handel, Haydn, and Bach, reflecting his later musical preferences, and readings from The Little Grey Men. His life, though marked by creative brilliance and personal tragedy, left an indelible mark on music history, forever shaping the psychedelic soundscape and the legacy of Songs By Pink Floyd.

[Excerpt: Glenn Gould, “Allemande from the Partita No. IV in D major”]

Discover more from A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.