In the annals of American history, certain symbols resonate deeply, evoking powerful emotions and shared experiences. Among these, the yellow ribbon tied around an oak tree stands out as a potent emblem of hope, homecoming, and national unity. This symbol gained prominence during the Iran hostage crisis of 1979-1981, when 52 Americans were held captive in Tehran for 444 long days. But the story of the yellow ribbon’s symbolism extends beyond this crisis, intertwining with a popular song and the unwavering spirit of a diplomat’s wife.

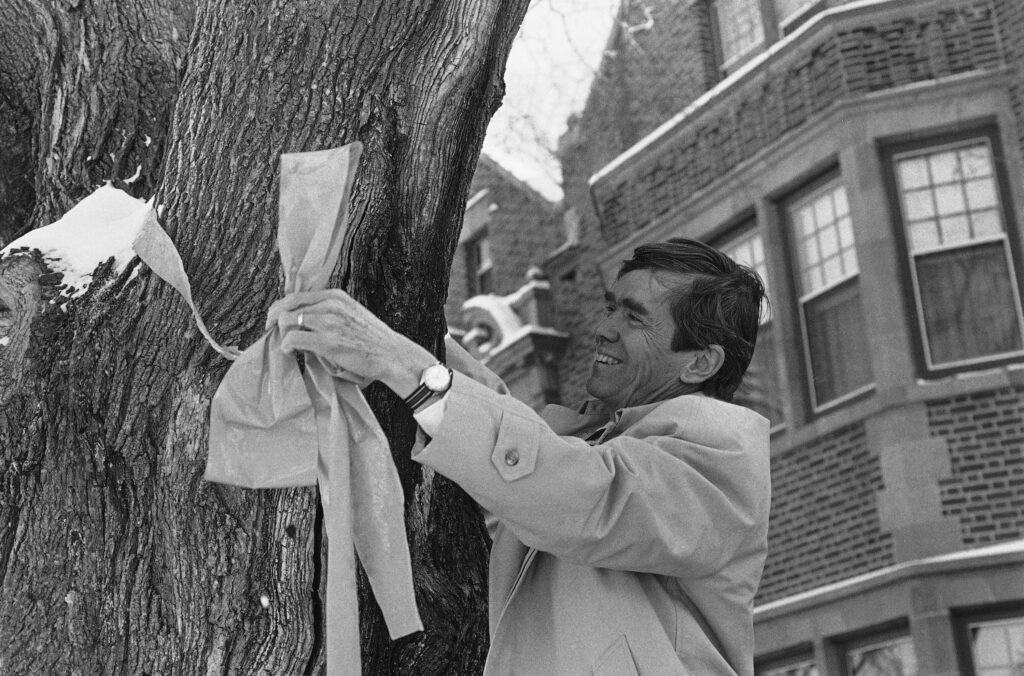

Bruce Laingen Yellow Ribbon

Bruce Laingen Yellow Ribbon

Penne Laingen and the Call for Yellow Ribbons

At the heart of this story is Penne Laingen, the wife of Bruce Laingen, the U.S. Chargé d’Affaires in Tehran and, in essence, the highest-ranking diplomat at the embassy during the hostage crisis. As the public grappled with the unfolding events, Penne Laingen emerged as a steadfast voice for the hostages and their families. While the nation seethed with frustration and anger, Penne advocated for a different approach – one of patient hope and constructive action.

In an interview that would prove pivotal, a reporter, expecting displays of outrage, was struck by Penne’s composure. When asked what Americans could do to support the hostages, Penne Laingen offered a suggestion that would capture the nation’s imagination:

“Tell them to do something constructive, because we need a great deal of patience. Just tell them to tie a yellow ribbon around the old oak tree.”

– Penne Laingen

This simple yet profound suggestion resonated deeply. But where did this idea of a yellow ribbon and an oak tree originate? The answer lies in a popular song that had captured hearts just a few years prior.

“Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree”: The Song’s Influence

Penne Laingen’s reference to tying a yellow ribbon was not arbitrary. It was a direct nod to the chart-topping song, “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree,” released in 1973 by Tony Orlando and Dawn. This song, penned by Irwin Levine and L. Russell Brown, tells the story of a man returning home from prison, uncertain if he would be welcomed back. He instructs his loved ones to tie a yellow ribbon around the old oak tree in town if they wanted him back; if there were no ribbon, he would stay on the bus.

The song became an instant sensation, topping charts worldwide and becoming an anthem of hope and homecoming. Its simple melody and poignant lyrics resonated with a public yearning for connection and reunion. The song’s popularity was so immense that it was covered by numerous artists across genres, including Frank Sinatra and Dolly Parton, further cementing its place in American popular culture.

While the song itself had no direct connection to hostage situations or international crises, its themes of waiting, hoping, and welcoming loved ones home perfectly mirrored the sentiments of Americans during the Iran hostage crisis. The yellow ribbon in the song became a powerful metaphor for the nation’s longing for the safe return of the hostages.

From Song Lyric to National Symbol: The Yellow Ribbon Takes Hold

Following Penne Laingen’s heartfelt suggestion, the yellow ribbon quickly transcended its origins in a song lyric to become a tangible symbol of national support. Families of the hostages were among the first to embrace the idea, tying yellow ribbons in their communities as a visual representation of their hope and solidarity.

The symbol spread rapidly across the nation. Yellow ribbons appeared on trees, front porches, car antennas, and lapels. It became a ubiquitous expression of support for the hostages and their families, a silent yet powerful message of “we remember, we care, and we wait for your return.”

The symbolism reached the highest levels of national visibility when Penne Laingen herself was asked to tie a yellow ribbon around the National Christmas Tree at the White House. This act solidified the yellow ribbon’s status as a national emblem of the hostage crisis and a symbol of collective hope.

Recognizing the burgeoning cultural significance of the yellow ribbon, the Library of Congress’s American Folklife Center undertook research in 1981 to document its history and cultural context. This further validated the yellow ribbon’s importance as a spontaneous and powerful expression of public sentiment.

Crowds in Frankfurt, Germany, greeted the released American hostages with yellow ribbons and signs, demonstrating the global reach of the symbol of hope and homecoming.

Homecoming and a Nation Adorned in Yellow

After 444 days of agonizing uncertainty, the Iran hostage crisis finally came to an end on January 20, 1981. The released hostages’ first stop was Wiesbaden, West Germany, before their return to the United States. Even in Germany, crowds gathered, waving yellow ribbons and homemade signs to welcome the weary travelers. The symbol had traveled with them, a testament to its global recognition.

Upon their arrival in the United States, the outpouring of emotion was overwhelming. At Stewart Airport in New York, a literal yellow carpet was rolled out, a poignant echo of the yellow ribbon tied to the oak tree. Ann Swift, one of the hostages, received a certificate commemorating her return, which included a piece of this yellow carpet – a tangible piece of history now preserved in the National Museum of American Diplomacy (NMAD).

The journey from the airport to their hotel, normally a short drive, stretched into over an hour as massive crowds thronged the streets, eager to catch a glimpse of the returning heroes. The Washington Post described the scene: “People abandoned their cars by the hundreds and flocked to glimpse buses as they passed… near the end of the route, bells rang and a packed crowd of several thousand went wild as the motorcade rumbled into view…”

Even the Super Bowl, coinciding with the hostages’ return, embraced the yellow ribbon. A giant yellow ribbon adorned the Superdome, cheerleaders waved yellow streamers, and players sported yellow stripes on their helmets. The “unofficial hostage theme song,” “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree,” played throughout the celebrations, solidifying the inextricable link between the song, the symbol, and the homecoming.

Penne and Bruce Laingen wave to cheering crowds lining the streets, a powerful image of homecoming and the nation’s collective relief and joy.

A Lasting Legacy: The Enduring Power of Symbolism

The Iran hostage crisis and the yellow ribbon became deeply intertwined in the American consciousness. As a Washington Post article noted, the crisis became a “national preoccupation,” and the yellow ribbon served as a unifying symbol during a period of national anxiety and hope. A telegram in the NMAD collection from employees of the Sun Valley Company in Idaho, who skied down Mount Baldy with torches forming a “flaming yellow ribbon,” further illustrates the nationwide embrace of the symbol.

A motorcade carrying the former hostages travels through Washington D.C., greeted by a sea of yellow ribbons, marking the culmination of a long-awaited homecoming.

The story of the yellow ribbon, the oak tree, and the song serves as a powerful reminder of the unifying potential of symbols during times of national significance. It highlights the ability of popular culture, in this case, a simple song, to intersect with real-world events and provide a framework for collective expression and emotional connection. It also underscores the quiet strength and impactful actions of individuals like Penne Laingen, who, in a moment of crisis, offered a symbol of hope that resonated across a nation and beyond.

The yellow ribbon around the oak tree, born from a song and embraced during a time of national crisis, remains a potent symbol of homecoming, hope, and the enduring human spirit. It reminds us of the challenging work of diplomacy and the unwavering support for those who serve on the frontlines.

References

Original article links and references would be listed here as in the original article.

Related Iran Hostage Crisis Content

Links to related content would be listed here as in the original article.