Updated on August 17th, 2024

Estimated reading time is 11 minutes.

“A FINE LITTLE GIRL, SHE WAITS FOR ME” These iconic words mark the beginning of the first verse of “Louie Louie,” a song that has resonated through generations. However, the song doesn’t actually start with this verse; it bursts into life with the unforgettable chorus: “Louie Louie, me gotta go.” From this point on, the track etches itself into the annals of rock & roll history.

The title itself, “Louie Louie,” deliberately omits a comma. This intriguing detail suggests that the singer may be directly addressing someone named Louie Louie. While one might initially assume Louie Louie is a shipmate, given the line “I sail the ship all alone,” it becomes clear the singer is traveling solo.

This article has been updated to include a section in brown print, providing further insights into the song’s fascinating story.

Some interpretations suggest the singer is speaking to a bartender on a Caribbean island. Regardless of the specific scenario, the core message is clear: the singer yearns to return home from the Caribbean Sea to his beloved, promising, “I’ll never leave again.”

Initially released in 1957 as the B-side to You Are My Sunshine, “Louie Louie” didn’t initially climb the national pop or R&B charts. Despite this slow start, it quickly gained traction among young bands, particularly in the Pacific Northwest, becoming a staple in their repertoire.

By 1961, Rockin’ Robin Roberts and the Wailers released a raw, garage-infused version of Louie Louie that became a regional hit, stretching from Oregon to British Columbia. It seemed every band in the area adopted it as their own. Then, in 1963, both Paul Revere & the Raiders and the Kingsmen released their versions almost simultaneously, further fueling the song’s growing momentum.

However, it was the Kingsmen’s rendition – heavily inspired by Roberts’ record – that propelled “Louie Louie” into a realm of legendary status. Critics and rock historians have spent decades searching for superlatives to adequately capture the visceral impact of hearing and feeling this version.

RichardBerry photo 1950s 800 crop copy

RichardBerry photo 1950s 800 crop copy

Richard Berry, in a publicity shot from the late 1950s, showcases the cool demeanor of an R&B star. The photo’s vintage aesthetic captures the era when “Louie Louie” was born.

The Enigmatic Vocals: Decoding the “Dirty” Lyrics of Louie Louie

The Kingsmen’s recording of “Louie Louie” is characterized by its raw, almost rudimentary production. Lead singer Jack Ely’s vocals, in particular, emerged as somewhat muffled and indistinct. This sonic ambiguity inadvertently sparked a nationwide phenomenon: millions of young listeners began to interpret “dirty” or suggestive lyrics within the seemingly incomprehensible vocal delivery.

Decades later, the esteemed New Yorker magazine delved into this intriguing aspect of the song’s history with an article provocatively titled, “Is This The Dirtiest Song Of The Sixties?“

The article reveals the technical limitations of the recording session: “On that April day in 1963, the only microphone available to Ely was located several feet above him, hanging from the ceiling. Ely was wearing dental braces, and his bandmates, who were gathered around Ely in a circle, played their instruments loudly. The result was an incomprehensible vocal that, in time, would make Ely the most celebrated interpreter of a song which is close to being pop Esperanto.”

Louie Louie endures as a quintessential rock & roll recording and stands as one of the most frequently recorded songs in the last sixty years of popular music. Its simple chord progression and adaptable lyrics contribute to its enduring appeal.

The chord progression, a straightforward A, D, E minor sequence, is remarkably accessible. As for the lyrics, the article humorously suggests, “it doesn’t matter how you sing them, or even really what you sing, though you might consider beginning with the words ‘Louie Louie / Oh no / Me gotta go.’ Really, though, the floor is yours. Sing your grocery list. Pull random words from a hat.”

The widespread belief in the early to mid-1960s that the Kingsmen had surreptitiously inserted obscene content into a song broadcast on public radio, accessible to young audiences, led to an official FBI investigation! This investigation persisted throughout 1965. However, unable to decipher Ely’s actual lyrics, even with expert analysis, the agency was ultimately forced to drop the case, leaving the mystery of the “dirty lyrics” unresolved.

While the complete history of Louie Louie is rich and multifaceted, this article focuses on providing readers with the original lyrics from Richard Berry’s 1956 recording alongside the more widely debated “dirty” lyrics attributed to the Kingsmen’s 1963 version.

Before proceeding further, it’s recommended to open a separate browser tab, access YouTube, and listen to both versions of the song while reviewing the lyrics presented below. This immersive experience will enhance your understanding of the nuances and evolution of Louie Louie.

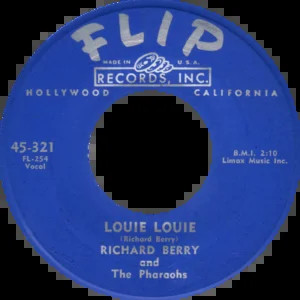

RichardBerry LouieLouie Flip 78 800

RichardBerry LouieLouie Flip 78 800

RichardBerry LouieLouie Flip 800

RichardBerry LouieLouie Flip 800

These vintage record labels from Flip Records highlight the original release of Richard Berry & The Pharaohs’ “Louie Louie” on both 78 rpm and 45 rpm formats, common for singles before 1958.

Richard Berry’s Original “Louie Louie” Lyrics

Here are the lyrics to “Louie Louie” as Richard Berry originally recorded them in 1956. Both sides of the record (Flip 254 and 321) are credited to Richard Berry and The Pharaohs. At the time of recording, The Pharaohs were one of several vocal groups Berry collaborated with.

The group members for this recording, listed alphabetically, were:

Godoy Colbert, first tenor

Noël Collins, baritone

Stanley Henderson, second tenor

Berry’s intention was to create a song that nodded to the then-popular calypso music, popularized in the US by Harry Belafonte. However, the song opens with a signature repetitive, doo-woppy bassline (“Duh duh duh—duh duh—duh duh duh”) that becomes a defining characteristic throughout the track.

Below are Berry’s lyrics, with punctuation added for clarity:

Louie Louie, me gotta go. Louie Louie, me gotta go.

Fine little girl, she wait for me. Me catch the ship across the sea. I sail the ship all alone. I never think I’ll make it home.

Louie Louie, I said me gotta go. Louie Louie, me gotta go.

Three nights and days, me sailed the sea. Me think of girl constantly. On the ship, I dream she there. I smell the rose in her hair.

Louie Louie, me gotta go. Well, Louie Louie, me gotta go.

Me see Jamaica Moon above. It won’t be long, me see me love. Me take her in my arms and then, I tell her I’ll never leave again.

Louie Louie, me gotta go. Louie Louie, me gotta go. I said me gotta go. I said me gotta go. Well, me gotta go.

Notably, Berry’s lyrics predominantly use “me” instead of “my,” a stylistic choice that contributes to the song’s unique character. The repetition of “Louie Louie, me gotta go” emphasizes the singer’s urgency and longing to return home.

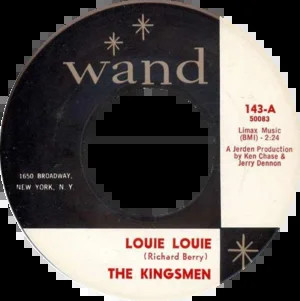

Kingsmen LouieLouie Jerden 800

Kingsmen LouieLouie Jerden 800

Kingsmen LouieLouie Wand 800

Kingsmen LouieLouie Wand 800

These record labels illustrate the Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” journey, initially released on Jerden Records before being picked up by Wand Records for nationwide distribution, signifying its growing popularity.

The Kingsmen’s Rendition: “Loowee Loowie” and Garage Rock Innovation

While Jack Ely’s distinctive, almost frantic vocal delivery commands most of the attention, it’s crucial to remember that The Kingsmen were a self-contained band who played their own instruments and sang. The lineup at the time of the recording included:

Lynn Easton, drums

Jack Ely, rhythm guitar

Don Gallucci, keyboards

Mike Mitchell, lead guitar

Bob Nordby, bass guitar

Here are the Kingsmen’s lyrics, again with punctuation added for clarity:

Louie Louie (oh, no), said me gotta go (yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah).

I said, Louie Louie (oh, baby), I said baby, we gotta go.

A fine little girl, she waits for me. Me catch the ship across the sea. Me sailed that ship all alone. Me never think how I’ll make it home

Louie Louie (yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah) I said we gotta go (oh, no). Said Louie Louie (oh, baby), said we gotta go.

Three nights and days I sailed the sea. Me think of girl (oh) constantly. On that ship, I dream she there. I smell the rose in her hair.

Louie Louie (oh, no) said we gotta go (yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah). Louie Louie (oh, baby) said we gotta go.

(Okay, let’s give it to them right now!)

Me see Jamaica, the moon above. It won’t be long me see me love. Me take her in my arms and then, I tell her I’ll never leave again.

Louie Louie (oh, no), said we gotta go (yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah). Said Louie Louie (oh, baby), said we gotta go. I said we gotta go now. Let’s hustle on out of here. Let’s go!

A close examination of Jack Ely’s vocals on the Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” from 1963 reveals that the lyrics are remarkably similar to Berry’s original. The primary lyrical differences are Ely’s pronunciation of the title as “Loowee Loowie” and his addition of interjections like oh-no, oh-baby, and numerous yeah’s throughout the song. These additions, while seemingly minor, contribute significantly to the Kingsmen’s energetic and raw interpretation.

Musically, the Kingsmen replaced the bass singer’s part with a prominent organ and substituted the instrumental bridge with a raucous guitar solo. Beyond these changes, the fundamental structure of the song remained intact.

The Kingsmen’s version abandoned the calypso feel of the original, instead embracing a raw, unrefined energy. Ely’s vocal performance sounds almost unhinged, while the band’s playing embodies an energetic sloppiness and crudeness (“Rehearse? Nah—we got this!”) that has led many rock historians to identify this recording as proto-garage, if not the definitive first successful example of garage rock’s raw sound.

* An infamous anecdote associated with the recording involves drummer Lynn Easton dropping his drumstick right after the second chorus, resulting in an audible exclamation, “Fuck!” inadvertently captured on the final take.

** Another notable imperfection occurs after the instrumental bridge and guitar solo. Ely misjudges the timing and comes in early with “Me see,” then has to pause and wait for the band to complete the bridge, further adding to the song’s raw and unrehearsed feel.

DaveMarsh LouieLouie later edition 600

DaveMarsh LouieLouie later edition 600

Dave Marsh’s comprehensive book dedicated to “Louie Louie” explores the song’s profound impact on rock and roll history and mythology. This later edition highlights its enduring legacy.

The Second Verse Controversy: Decoding the Misheard Lyrics

Reader Jim Miller highlighted in a comment that many listeners interpreted a portion of the second verse as containing sexually suggestive lyrics, specifically, “Every night at ten, I laid her again. I fucked that girl all kinds of ways.”

Adding to the lyrical ambiguity, the New Yorker article mentioned earlier noted that others misheard the same lines as, “At night at ten, I lay her again. Fuck you girl, oh, all the way.”

These misinterpretations, fueled by Ely’s garbled delivery and the song’s raw energy, contributed significantly to the “Louie Louie” lyrical controversy and its reputation as a potentially “dirty” song.

Kingsmen LouieLouie Wand Ely dj 800

Kingsmen LouieLouie Wand Ely dj 800

Post-legal settlement in 1966, Wand Records pressings of “Louie Louie” were updated to credit “Lead vocal by Jack Ely,” distinguishing them from earlier pressings and becoming more sought-after by collectors.

Chart Performance and Cultural Impact of Louie Louie

While Richard Berry’s original version reportedly received some airplay and sold over 100,000 copies, it did not break into the national best-selling charts. In contrast, despite the swirling controversy, the Kingsmen’s Louie Louie became a massive hit. It reached #1 on the Cash Box chart for two weeks in January 1964.

Louie Louie held the top spot on Cash Box until the arrival of The Beatles in May, marking a significant shift in the musical landscape. On the Billboard charts, it peaked at #2 and #3 for six weeks between December 1963 and January 1964, narrowly missing the coveted #1 position.

The song’s controversial reputation led to de facto bans on some radio stations. In Indiana, Governor Matthew Welsh, believing the lyrics to be obscene, purportedly banned the record from airplay across the state, though the legal basis for such a ban remains unclear. This piecemeal censorship likely impacted the song’s potential chart ascent on Billboard.

Interestingly, in May 1966, Louie Louie experienced a resurgence, re-entering the Cash Box Top 100 for five weeks and peaking at #65, demonstrating its enduring appeal.

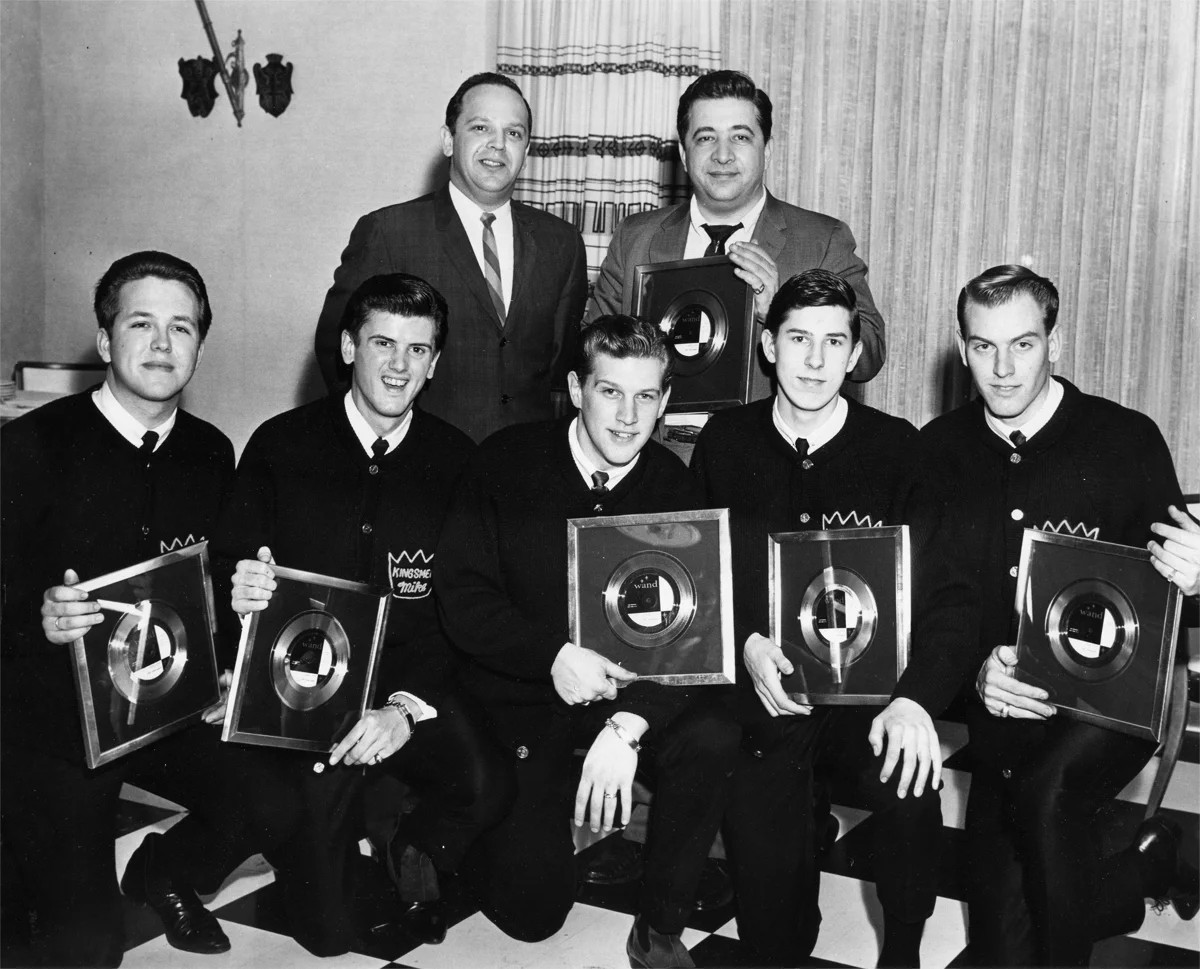

Kingsmen LouieLouie GoldRecord 1200

Kingsmen LouieLouie GoldRecord 1200

The Kingsmen received an in-house gold record award from Wand Records for “Louie Louie,” although personnel changes had already occurred within the band by this time.

Louie Louie Sales and Enduring Legacy

Estimates for the Kingsmen’s Louie Louie single sales range from 10 million to over 12 million copies, with cover versions potentially adding another 300 million to the overall figure, according to Wikipedia contributors, citing liner notes from the Rhino Records compilation The Best Of Louie Louie.

However, music industry historian Joseph Murrells, in Million Selling Records From The 1900s To The 1980s, lists the record simply as a million-seller. Notably, despite its widespread popularity and sales, Louie Louie has never been officially certified Gold by the RIAA.

An article from The Los Angeles Daily News in 1986, “After 23 years, ‘Louie Louie’ Cooler Than Ever,” makes the astonishing claim that cover versions of Louie Louie may have sold as many as 300 million records. This figure, while impressive, would require each of the estimated thousand cover versions to average 300,000 copies sold, a highly improbable scenario.

Regardless of the precise sales figures, Louie Louie remains a cornerstone of rock & roll history. Its simple structure, infectious energy, and lyrical ambiguity have cemented its place as a timeless anthem and one of the most recorded songs of the past sixty years.

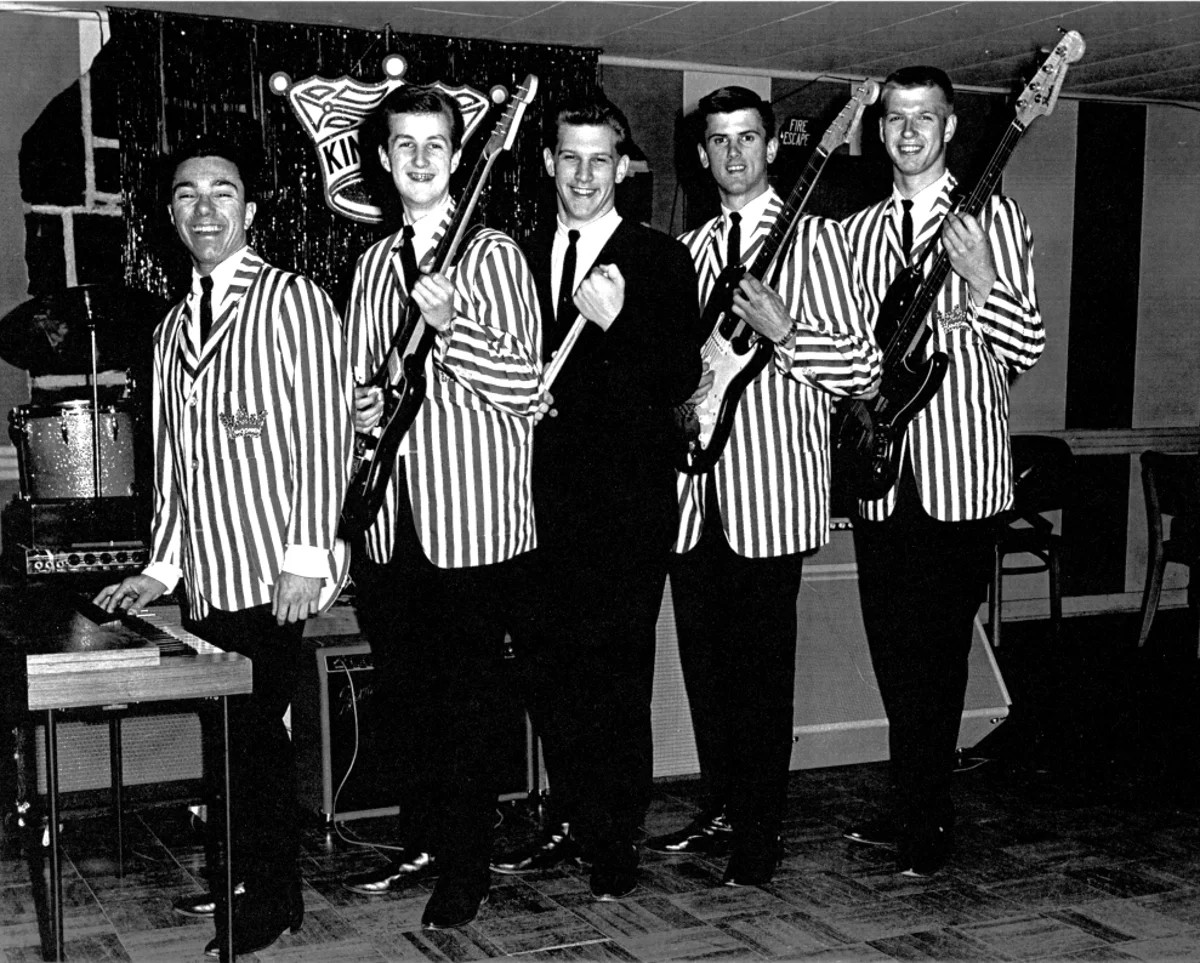

TheKingsmen 1963 1200

TheKingsmen 1963 1200

The Kingsmen in their early days, circa 1963, captured in a photo that embodies the youthful energy and raw spirit of garage rock that “Louie Louie” helped define.

FEATURED IMAGE: The lead image of this article is a cropped section from this full band photo of the Kingsmen from the early 1960s. The lineup pictured from left to right includes Don Gallucci, Jack Ely, Lynn Easton, Mike Mitchell, and Bob Nordby. Photos featuring Ely during his time with the band are relatively rare, making this image historically significant.

For those seeking deeper exploration, numerous websites are dedicated to the Kingsmen and the phenomenon of “Louie Louie.” One recommended resource is The Louie Report (“The blog for all things LOUIE LOUIE”), accessible here.

Further reading is available in Dave Marsh’s definitive book, Louie Louie: The History and Mythology of the World’s Most Famous Rock ‘N’ Roll Song.

Neal Umphred

A mystically liberal Virgo who finds solace in solitary city walks on rainy nights, accompanied by an umbrella and a flask of aged Laphroaig.

Living by the maxims: “I always tell the truth—that way I don’t have to remember what I said” and “It ain’t what you know that gets you into trouble—it’s what you know that just ain’t so.”

Past lives include roles as a puppet, pauper, pirate, poet, pawn, and college dropout (twice). Occupational experiences range from bartender and jewelry engraver to landscape artist and FEMA crew chief following the Great Flood of ’72—a job never to be regretted leaving.

Author of the final record collector’s price guides for O’Sullivan Woodside (1985-1986) and the original author of the Goldmine price guides for record collectors (1986-1996), often known as the “Price Guide Guru.”

Remember the guru’s words…

Related Reads: