As a passionate advocate for World Literature and foreign cinema, I was immediately captivated by the Irish animated film, “Song Of The Sea.” This award-winning movie is not just visually stunning; it’s a rich tapestry of Celtic mythology that has resonated deeply with audiences and my students alike year after year.

Today, I want to share why “Song of the Sea” is a must-watch and an exceptional resource for enriching your classroom’s literary analysis. If you’re looking to introduce captivating Celtic mythology into your curriculum, explore this ready-to-go mini unit to get started today!

In my previous discussions on diversifying classroom mythology, I’ve highlighted the often-overlooked beauty of Celtic traditions. While Greek and Roman mythology rightly hold a significant place in education, Celtic mythology offers equally compelling narratives and cultural insights. “Song of the Sea” provides a perfect entry point to this fascinating world, especially for students who may only associate Celtic culture with St. Patrick’s Day leprechauns.

Centering a unit around “Song of the Sea” elevates the study of Celtic mythology by seamlessly integrating literary elements such as parallel plotlines, rich symbolism, and effective use of flashbacks. To fully appreciate the film’s depth, it’s essential to understand the mythological figures that inspire its narrative. Let’s delve into some key Celtic deities featured in the movie:

Exploring Mac Lir: God of the Sea

Manannán mac Lir, meaning “son of the sea,” is a prominent deity in “Song of the Sea.” A central figure in Celtic mythology, he belongs to the Tuatha Dé Danann, a mystical Irish race. Often depicted as the protector of the island, Manannán mac Lir wields magic to create mists, warding off invaders and safeguarding his realm.

The film “Song of the Sea” mirrors elements of Manannán mac Lir’s mythology, particularly his experience with profound loss. Both the deity and the human character Connor grapple with immense grief after losing loved ones. This parallel storyline allows viewers to explore the consuming nature of grief and the journey towards finding peace and healing, themes powerfully portrayed through the lens of Celtic myth.

Understanding Macha: A Powerful Mother Figure

Macha presents a complex figure within Celtic mythology, often understood as part of a triad of female deities representing different aspects of womanhood. In the context of “Song of the Sea,” we focus on Macha as the mother, drawing from “The Curse of Macha.”

This tale recounts Macha’s tragic race while pregnant with twins, forced to demonstrate her incredible speed. Her subsequent curse upon the men present, inflicting them with labor pains, reflects her endured suffering. In “Song of the Sea,” Macha embodies a mother overwhelmed by the desire to shield her son, Mac Lir, from pain. However, her attempt to remove pain inadvertently turns people to stone, highlighting the nuanced consequences of even well-intentioned actions.

Discovering Selkies: Mythical Seal People

Selkies, enchanting creatures from Scottish and Irish folklore, are central to the narrative of “Song of the Sea.” Predominantly female, though male selkie tales exist, they are beings capable of transforming between seal and human forms. By shedding their seal skin on land, they become human; to return to the sea, they must reclaim their skin.

Selkie stories often carry a melancholic undertone, particularly those involving women. Some are tricked by men who steal their seal skins, forcing them into unwanted marriages. Others fall in love with mortals, yet their dual nature creates inherent sadness, as they are beings divided between two worlds. Folklore sometimes suggests a selkie woman will have children, one destined for the sea and one for land.

In “Song of the Sea,” Bronagh, the mother, is a selkie and mother to Ben and Saoirse. Ben, the elder child, is young when Bronagh vanishes into the sea one night, pregnant with Saoirse. Saoirse, growing up nonverbal, discovers a white coat – a seal skin – in a trunk. Drawn to it, she transforms into a seal upon entering the sea. Without her coat, Saoirse weakens. Ben’s journey reveals that Saoirse and their mother are both selkies, embarking them on a quest intertwined with magic and familial love.

Yeats and the Echoes of Irish Tradition in “Song of the Sea”

“Song of the Sea” beautifully connects to the works of William Butler Yeats, the renowned Irish poet. The film’s opening lines are directly inspired by Yeats’ poem, “The Stolen Child.”

Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.

Yeats, a figurehead of Irish Nationalism, sought to revive Ireland’s cultural roots, deeply embedding Celtic mythology and lore into his poetry. Exploring Yeats alongside “Song of the Sea” provides a rich context for understanding the film’s themes and its connection to broader Irish cultural identity.

Director Tomm Moore’s inspiration for “Song of the Sea” arose from a personal experience. Witnessing the tragic sight of dead seals on a beach, a local woman lamented the loss of reverence for seals in modern times, contrasting it with older days when they were respected. This poignant moment underscores the film’s subtle commentary on the fading of traditional beliefs and the importance of reconnecting with nature and folklore, reflected in the fae’s departure from the human world depicted in the film’s opening.

Symbolism and Rich Celtic Traditions Woven Throughout

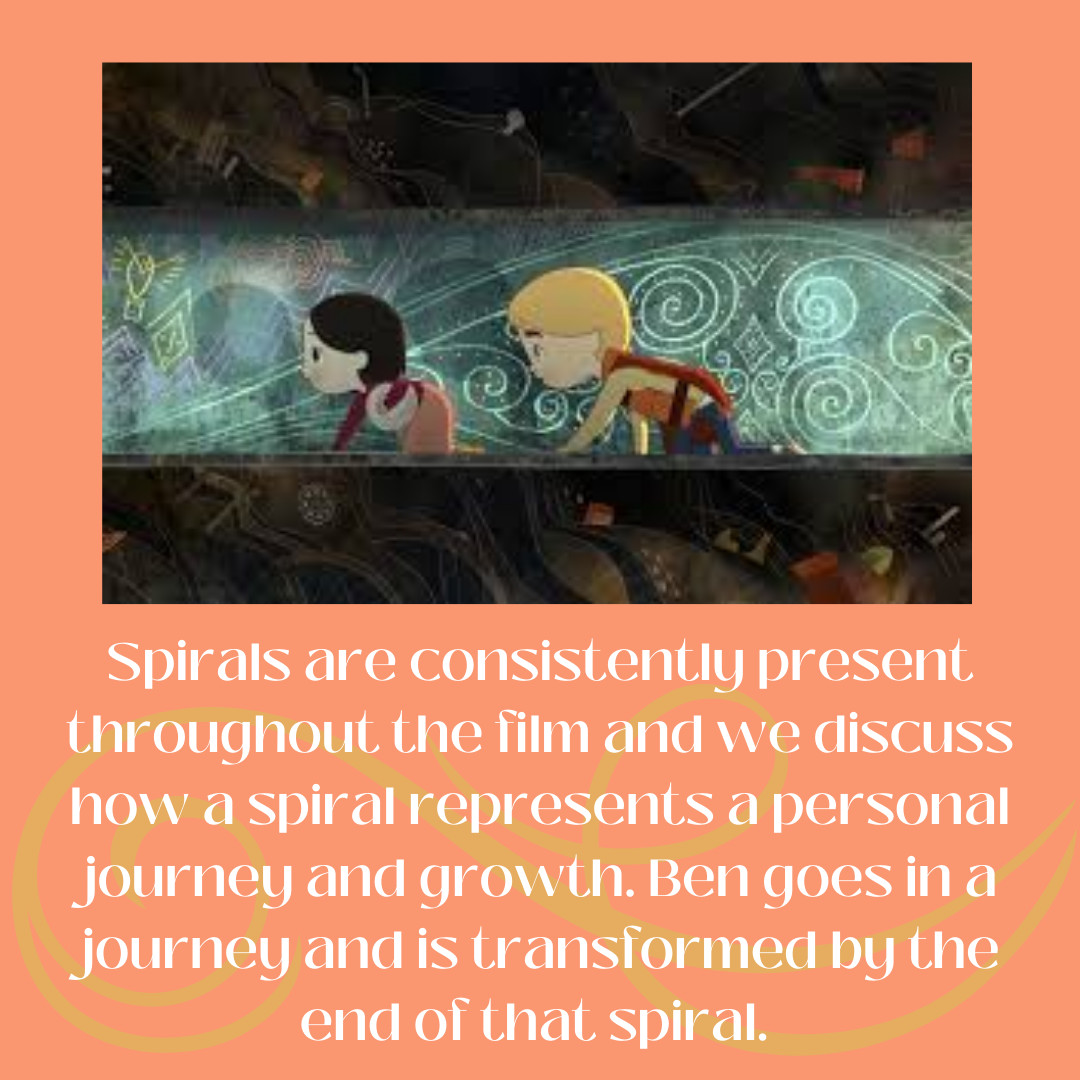

“Song of the Sea” is deeply symbolic, drawing from rich layers of Fae lore and Celtic traditions. My students and I spend considerable time unraveling the symbolism within the film and how it reinforces its central themes.

Spirals, a recurring motif, represent journeys of personal growth and transformation in ancient Celtic symbolism. Ben’s journey throughout the film embodies this spiral, showcasing his evolution. Circles and fairy mounds, also prevalent, further root the film in Celtic visual language. The three fairies act as guides for Ben and Saoirse, embodying archetypal figures in folklore.

Even character names carry symbolic weight. Saoirse, meaning “freedom,” reflects her role in liberating the fairy world from threats. Bronagh, meaning “sadness,” poignantly captures the mother’s heartbreaking departure in the film. As a mother myself, Bronagh’s farewell resonates deeply, adding emotional depth to the narrative.

The symbolic depth of “Song of the Sea” is vast, offering endless avenues for analysis. This exploration merely scratches the surface. Introducing students to this often-unfamiliar world of Celtic mythology through such a beautiful film is incredibly rewarding.

Integrating “Song of the Sea” into a Celtic Mythology mini-unit is consistently a highlight for my students. Our discussions delve into parallel plots, Irish traditions, mythology, and symbolism, creating a comprehensive and engaging learning experience.

Ready to bring this captivating study to your classroom? Visit my store to purchase this ready-to-go mini unit today and embark on a magical journey into Celtic mythology with your students!

Join My Newsletter!

Want weekly tips and resources for teaching secondary English delivered straight to your inbox? Click here to join!