As a passionate advocate for World Literature and foreign films, I was immediately captivated by the enchanting Irish animated movie, Song of the Sea. This award-winning film seamlessly blends stunning visuals with rich Celtic mythology, creating an unforgettable cinematic experience. Year after year, my students also fall under its spell, making it a valuable tool for literary analysis in the classroom.

This post will explore the captivating world of Song of the Sea movie and delve into why it’s an exceptional choice for enriching your curriculum with Celtic mythology.

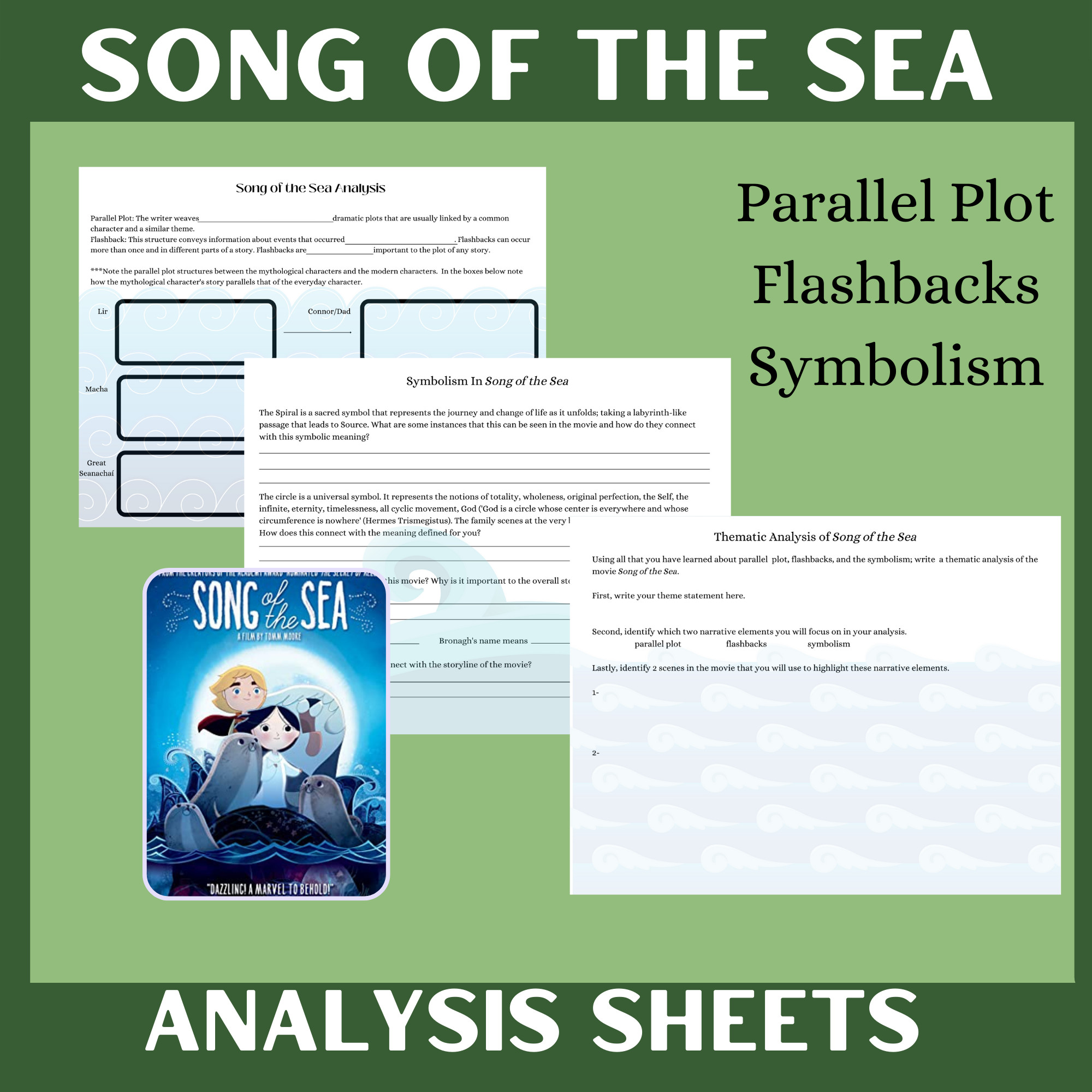

If you’re eager to incorporate this engaging approach to Celtic mythology into your lessons, you can discover a ready-to-use mini unit in my store today!

In my previous articles, I’ve emphasized the importance of diversifying mythology in education. Celtic mythology, often overshadowed by Greek and Roman narratives, offers a wealth of beautiful and intricate stories.

By the time students reach the 10th grade, they often possess a solid foundation in Greek and Roman mythology. However, their exposure to Celtic culture may be limited to stereotypical figures like leprechauns. Using the Song of the Sea movie as a central point of study elevates this exploration, seamlessly integrating literary elements such as parallel plotlines, symbolism, and flashbacks.

To begin, we can explore the fascinating mythology that underpins the film:

Unveiling Celtic Deities in Song of the Sea

Mac Lir: The God of the Sea

Manannán mac Lir, meaning “son of the sea,” is a prominent Celtic deity featured in the movie. A significant figure in Irish mythology, he belongs to the Tuatha Dé Danann, a mystical race in Irish lore. Often portrayed as the protector of the island, Manannán mac Lir wields magic, notably creating a mystical mist to disorient and deter invaders.

In the Song of the Sea movie, mirroring certain Celtic tales, Lir experiences profound loss and grief. This is reflected in the human character Connor, who tragically loses his wife in the film’s opening scenes. Both narratives poignantly illustrate the debilitating impact of grief and the eventual journey toward finding peace.

Macha: The Complex Mother Goddess

Macha presents a multifaceted deity, often understood as part of a triad of female figures representing the Maiden, Mother, and Crone archetypes. For our study focusing on the Song of the Sea movie, we concentrate on Macha as the mother figure, drawing from the myth “The Curse of Macha.”

In this tale, Macha, pregnant with twins, is known for her incredible speed. Against her will and knowing the risks to her pregnancy, she is forced to race. In retribution, she curses the men present with labor pains, making them experience her suffering.

In the Song of the Sea movie, Macha is also depicted as a mother, consumed by a desire to alleviate her son Mac Lir’s pain. However, her method—taking away pain—unintentionally turns people into stone, highlighting the complex and sometimes detrimental nature of even well-intentioned actions.

Selkies: Creatures Between Two Worlds

Selkies, enchanting mythological beings, are deeply rooted in Scottish and Irish folklore. While typically depicted as female, male selkies also appear in some stories.

Selkies are seals in the ocean who can shed their skin upon reaching land, revealing a human form. To return to the sea, they must reclaim their seal skins and re-enter the water.

Many selkie tales, particularly those involving women, carry a sense of melancholy. Some selkies are trapped by humans who discover and conceal their seal skins, forcing them into unwanted marriages. Others fall in love with mortals and choose to marry them.

Regardless of the circumstances, a selkie’s life in the human world is often incomplete, as they are beings meant to live in the sea. Some legends suggest that a selkie woman will have children, one destined for the human world and another for the sea.

In the Song of the Sea movie, Bronagh, the mother, has two children: Ben and Saoirse. Ben, the elder, is young when his pregnant mother vanishes into the sea one night, never to be seen again. Saoirse is born on the same night.

By age seven, Saoirse is still unable to speak. One night, she discovers a white coat in a chest and is drawn to it. Upon wearing it and entering the sea, she transforms into a beautiful white seal. Without her coat, Saoirse weakens, her life force diminishing. Ben embarks on a journey throughout the movie, eventually discovering that both Saoirse and their mother are selkies.

Yeats and the Echoes of Irish Tradition in Song of the Sea

The Song of the Sea movie provides a powerful link to the works of renowned Irish author William Butler Yeats. The film’s opening lines are directly taken from his poem, “The Stolen Child.**”

“Come away, O human child!

To the waters and the wild

With a faery, hand in hand,

For the world’s more full of weeping than you can understand.”

Yeats was deeply involved in Irish Nationalist movements. His desire to reconnect Ireland with its cultural roots led him to heavily incorporate Celtic mythology and folklore into his writing. Exploring “The Stolen Child” alongside the Song of the Sea movie offers a rich opportunity to discuss Yeats’s work and Celtic mythology in the classroom.

However, the film’s creator, Tomm Moore, has cited a different inspiration for the selkie narrative. During a family holiday, Moore witnessed the tragic sight of dead seals washed ashore. A local woman lamented that such disrespect for seals would not have occurred in earlier times when they were revered. This real-world event likely influenced the film’s poignant opening lines, suggesting the departure of the Fae from a world that no longer values them.

Symbolism and Celtic Traditions Woven into Song of the Sea

The Song of the Sea movie is incredibly layered with symbolism and Fae lore. My students and I dedicate significant time to analyzing the numerous symbols within the film and how they contribute to its overarching themes.

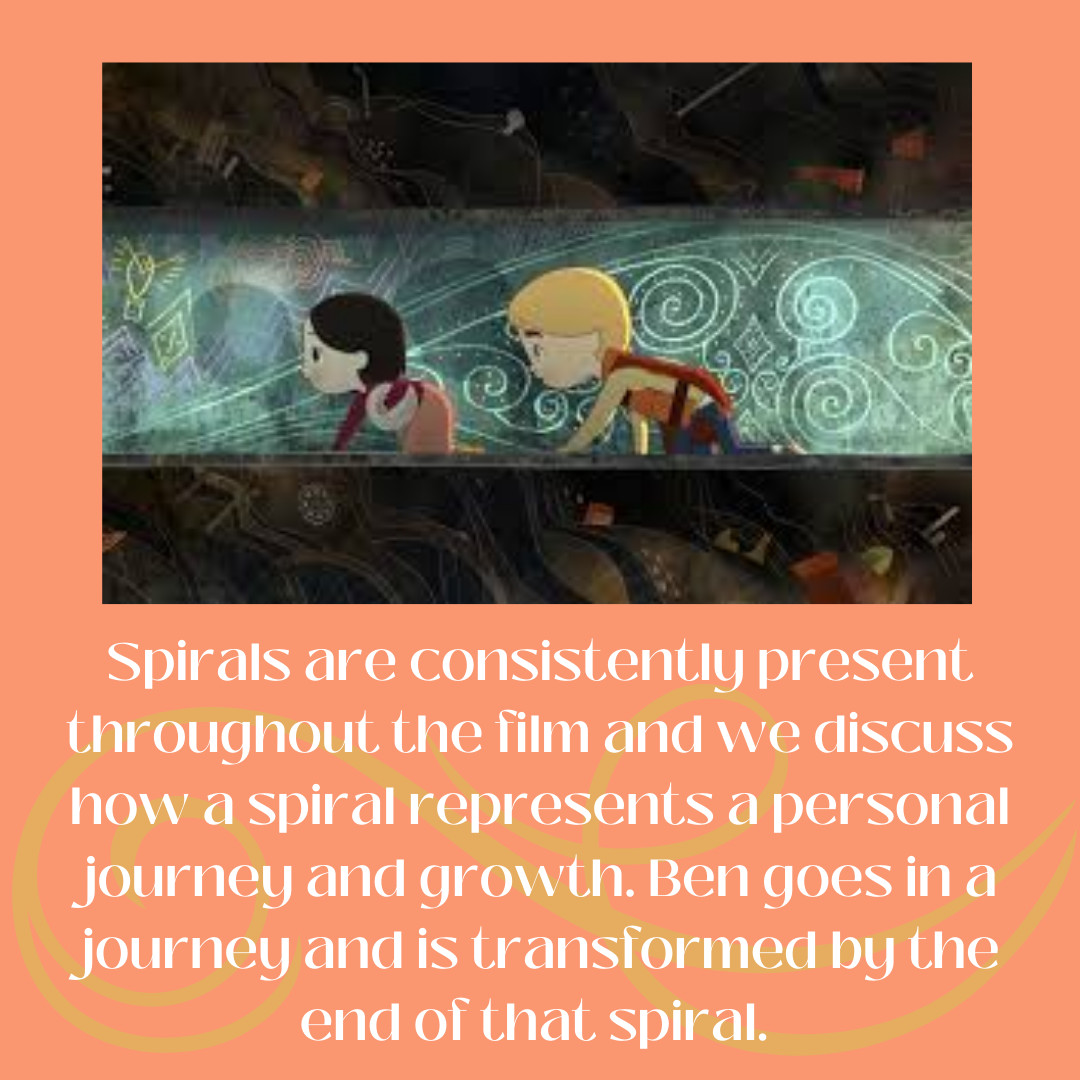

Spirals, for instance, appear repeatedly throughout the movie. We discuss how, in ancient Celtic tradition, spirals represented personal journeys and growth. Ben’s journey in the film and his transformation by its end perfectly embody this symbolism.

Circles and fairy mounds are also recurring visual motifs. Additionally, three fairies act as crucial guides for both Saoirse and Ben.

Even character names hold symbolic weight. Saoirse, meaning “freedom,” reflects her role in freeing the fairy creatures trapped in the human world. Bronagh, meaning “sadness,” poignantly foreshadows the heartbreaking nature of her departure in the film’s final scenes, a sentiment deeply felt by any parent.

I could easily dedicate numerous posts to the profound symbolism embedded within this film; here, I’ve only touched upon the surface. It’s truly remarkable to introduce students to a world they likely haven’t encountered before.

Exploring Celtic Mythology and the Song of the Sea movie is consistently a rewarding experience for my students. We engage in in-depth discussions about parallel plots, Irish traditions, mythology, and symbolism, fostering a deeper understanding and appreciation for storytelling.

If you’re ready to embark on this enriching journey with your class, explore my ready-to-go mini unit today!

Join my Newsletter!

Want weekly teaching tips and resources for secondary English delivered directly to your inbox? Click here to subscribe!

Share this:

Like Loading…