The lines are instantly recognizable, a raw expression of weekday dread amplified to an anthem: “Tell me why! I don’t like Mondays! Tell me why! I don’t like Mondays! Tell me why! I don’t like Mondays! I want to shoot the whole day down.” This potent chorus, punctuated with the stark question, “Which side are you on?”, catapulted the Irish band The Boomtown Rats and their frontman Bob Geldof into global consciousness with their 1979 hit, “I Don’t Like Mondays.” While seemingly a straightforward teenage lament against the start of the work week, the song delves into far darker and more complex territory, inspired by a chilling act of senseless violence. For those familiar with deeper cuts of musical storytelling, perhaps through explorations like Pat’s analyses of “Little Sadie” and “Cocaine Blues,” “I Don’t Like Mondays” offers a starkly modern murder ballad, trading traditional narrative for a thematic exploration of societal unease and the disturbing banality of violence in the late 20th century and, tragically, continuing into our present day.

It’s tempting to assume the song’s selection is merely a Monday morning whim, a relatable groan echoing the collective sentiment of countless individuals facing the weekly grind. And indeed, the simple, surface-level interpretation of “I don’t like Mondays” as a universal dislike for the beginning of the week is undoubtedly a key component of its widespread appeal. This accessibility, this immediate resonance with a shared feeling, however trivial, opens a door to understanding the song’s deeper, more unsettling layers.

“I Don’t Like Mondays” serves as a portal, not just into a more abrasive, punk-infused style of songwriting, marked by a certain youthful defiance, but also into the uncomfortable space where art attempts to grapple with incomprehensible violence. The real-life events that underpin this song are not rooted in motives of passion, revenge, or material gain; they are chillingly random, connecting perpetrator and victims through nothing more than proximity and circumstance. This departure from traditional crime narratives, centered on discernible motivations, pushes “I Don’t Like Mondays” into a realm of profound and disturbing questions about the nature of violence itself.

While this website generally refrains from directly addressing breaking news, particularly the agonizingly frequent occurrence of school shootings, to maintain focus on music rather than fleeting headlines and their associated political maelstrom, the story behind “I Don’t Like Mondays” compels consideration. This reluctance stems partly from a desire to avoid sensationalism and a recognition of the potential for unintended consequences when discussing such tragedies.

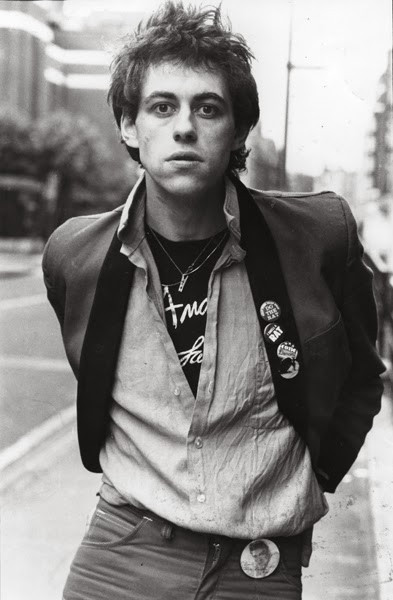

Bob Geldof

Bob Geldof

The concern, particularly with school shootings, revolves around the disturbing notion that some perpetrators may be driven, in part, by a twisted desire for notoriety, a desperate attempt to achieve a perverse form of significance through horrific acts. While this platform operates far outside the sphere of mainstream fame-making machinery, the ethical tightrope of discussing such events in any public forum remains. The necessity of processing trauma through artistic expression must be carefully balanced against the potential, however remote, of contributing to the very cycle of violence it seeks to understand. “I Don’t Like Mondays” itself grapples with this very dilemma, a point not lost on Bob Geldof in crafting the song.

“I Don’t Like Mondays” provides a crucial lens through which to examine these complex issues. Its selection for discussion here is driven by this critical relevance, and also by a personal connection to the song’s impact on musical development. For an adolescent navigating the turbulent waters of musical boundaries and rebellious expression, The Boomtown Rats, largely due to the controversy surrounding “Mondays,” were a band of significant interest. Recapturing the precise emotional landscape of youth is a challenge, yet “I Don’t Like Mondays” retains the power to evoke that unfocused, potent adolescent discontent. It offers a kind of cathartic “escape” into senselessness, mirroring the very feelings of being surrounded by the inexplicable that often characterize adolescence itself.

While not a constant presence in the soundtrack of life, “I Don’t Like Mondays” resurfaced with renewed resonance during the preparation for this analysis. Deeper layers within the song emerged, prompting a re-evaluation of its meaning, particularly the dynamic between the questioner and the answerer in the iconic refrain. Does one identify with both? Or is the power in the tension between them?

Fine Arts: The Album and the Anthem

“I Don’t Like Mondays” first appeared on The Boomtown Rats’ third studio album, aptly titled The Fine Art of Surfacing, released in October 1979.

Listen to this recording on YouTube here.

Stylistically, the song stands apart from the rest of the album’s tracks. Its punk ethos is more attitudinal than sonic. Geldof initially envisioned it as a B-side, yet its live performances in the United States garnered unexpected enthusiasm. This positive reception led to a more prominent release, ultimately propelling it to become the band’s most commercially successful hit. Similar to Bruce Springsteen’s “41 Shots (American Skin),” which also sparked immediate reactions, it raises the question of whether initial audiences truly grasped the song’s depth beyond its emotionally charged chorus. Intriguingly, Geldof himself has noted that it took six weeks after the song’s initial release for newspapers to connect it to the real-life event that served as its grim inspiration.

Monday Morning in San Carlos: The Real Story Unfolds

The catalyst for “I Don’t Like Mondays” was a news report detailing a school shooting in San Carlos, a neighborhood in San Diego. In January 1979, while at a university radio station in Atlanta, Geldof encountered the story via the station’s telex machine. Sixteen-year-old Brenda Ann Spencer had opened fire on students at Cleveland Elementary School from her house across the street. Her actions resulted in the wounding of eight children and a police officer, and the tragic deaths of the school’s principal, Burton Wragg, who was attempting to protect the children, and the school’s janitor, Michael Suchar, who in turn was trying to aid Wragg. Remarkably, no children succumbed to their injuries, a fact attributed to sheer fortune amidst the chaos.

Spencer surrendering to police

Spencer surrendering to police

In the aftermath of the shooting, before surrendering to police, Spencer was contacted by a local reporter via phone. When asked to explain her motive, her reported response was chillingly flippant: “I don’t like Mondays. This livens up the day.” Accounts of the event, such as those published by the New York Daily News and Mental Floss, provide further details of the tragic incident. Spencer ultimately pleaded guilty to two counts of first-degree murder and assault with a deadly weapon, receiving a sentence of 25 years to life. Despite multiple parole hearings, she remains incarcerated, with her next hearing scheduled for 2019, marking forty years since the devastating crime.

Geldof recounts the song’s creation, stating: “Not liking Mondays for a reason for doing somebody in is a bit strange. I was thinking about it on the way back to the hotel [after the radio interview], and I just said ‘Silicone chip inside her head had switched to overload [and] wrote that down. And the journalists interviewing her said. Tell me why?’ It was such a senseless act. It was the perfect senseless act and this was the perfect senseless reason for doing it. So perhaps I wrote the perfect senseless song to illustrate it. It wasn’t an attempt to exploit tragedy.”

Brenda Ann Spencer

Brenda Ann Spencer

Over the years, Brenda Ann Spencer’s narrative surrounding the shooting has proven inconsistent. However, examining available sources paints a bleak picture of her adolescence. Raised in a broken home, she reportedly lived with her father in a house filled with liquor bottles, sleeping on a shared mattress on the floor. Disturbingly, the .22 caliber rifle used in the shooting was a Christmas gift from her father, which Spencer later claimed she interpreted as encouragement to commit suicide.

Whether “I Don’t Like Mondays” itself is a “senseless song,” as Geldof muses, is debatable. The very act of grappling with the event through songwriting, of seeking to find artistic expression within such bleakness, suggests otherwise. The song powerfully captures a disturbing confluence of nihilism, adolescent alienation, and random violence. It echoes themes explored by Shaleane in her 2012 analysis of Bruce Springsteen’s “Nebraska,” particularly the exploration of a pervasive “meanness in this world.”

Youthful Transgressions and Lingering Controversy

“I Don’t Like Mondays” gained traction through live performances before audiences fully grasped the gravity of its subject matter. When Spencer’s family became aware of the song, they reportedly threatened legal action and attempted to block its release in the United States. Radio stations in San Diego, understandably sensitive to the community’s trauma, refused to play the song. Airplay was limited in other US markets due to the ongoing controversy. However, for some, including the author of the original article, this very controversy added to The Boomtown Rats’ rebellious appeal.

In a 1981 interview on The Merv Griffin Show, Geldof addressed the controversy and the challenges the band faced in securing radio airplay. The band performed the song prior to the interview, an appearance worth watching not only for the performance itself but also for Griffin’s genuinely bewildered, yet good-natured, disbelief that Geldof and his band were not clad in traditional Irish sweaters singing “Danny Boy.”

Geldof wryly introduces the performance by lamenting the “burden” of having to perform the song repeatedly, already hinting at the weariness that would later become associated with its massive success. With a touch of irony, he positions it as a protest song, performed on the show “against the current gun laws in America,” a statement that, while capturing the general sentiment, lacks precise political focus.

The performance itself, viewed through a contemporary lens, possesses a certain youthful earnestness that borders on unintentional comedy. Geldof himself has acknowledged his youthful abrasiveness, admitting to being argumentative for the sake of argument, a self-described “complete pain.” The interview with Griffin touches upon the impact of restricted airplay, yet notably avoids any in-depth discussion of the song’s disturbing subject matter.

Towards the interview’s conclusion, Geldof anticipates the growing influence of music videos as a promotional medium. The Boomtown Rats’ music video for “Mondays” is a quintessential example of early 80s music video aesthetics, a blend of theatrical amateur acting and then-cutting-edge production values. In a subsequent interview with the video’s producer, Geldof reveals a chilling detail:

“She [Spencer] wrote to me, saying she was glad she’d done it, because I’d made her famous; which is not a good thing to live with.”

This revelation brings the discussion full circle, returning to the uncomfortable issue of fame and infamy. Previous discussions have explored the “there are no words” rationale for why certain horrific events resist musical interpretation. Conversations with artists have also touched upon the artistic, moral, and emotional complexities of embodying the perspectives of both real and fictional killers in song. However, the added layer of a perpetrator seemingly reveling in the notoriety derived from the song is a particularly disturbing and perhaps unprecedented element. The song undeniably amplified the story’s reach far beyond its initial news cycle. While the burden of Spencer’s actions rests solely with her, not with Geldof, the uncomfortable reality persists that such publicity could, however unintentionally, become a perverse draw for other troubled individuals. Geldof, as an artist, responded to a shocking event, giving voice to his own reaction and, perhaps, to the inarticulate anxieties of listeners. This function, however, is not without inherent risks.

Conversely, Geldof strategically downplays the graphic details of the tragedy from the song’s outset. Despite the starkness of certain lines, “I Don’t Like Mondays” avoids becoming a purely narrative ballad detailing the event. This artistic choice likely served a dual purpose: mitigating potential legal repercussions and broadening the song’s accessibility. This thematic approach, rather than explicit storytelling, arguably contributed to the song’s wider appeal and radio-friendliness. The “Mondays” refrain, catchy and relatable, allowed listeners, from disgruntled office workers to angsty teenagers, to connect with the song’s sentiment without necessarily confronting the horrific specifics of its origin.

The song’s sing-along quality stems from multiple sources. Firstly, it taps into the universal stress associated with the start of a new week, aligning it with anthems of escapism like Todd Rundgren’s “Bang the Drum All Day” or Richard Thompson’s “I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight.”

Secondly, it resonates deeply with adolescent angst, that tumultuous period of life characterized by upheaval and uncertainty, where emotions are intense and the world often feels profoundly unjust. Regardless of the senseless act that inspired it, the feelings of senselessness, rage, and frustration are intensely relatable to a specific age group. It becomes an adolescent cri de coeur.

Yet, the song’s appeal extends beyond adolescence. Ultimately, “I Don’t Like Mondays” resonates with wider audiences precisely because it allows both singer and listener to inhabit both sides of the central refrain: “Tell me why!” and “I don’t like Mondays!” It acknowledges the simultaneous yearning for meaning and the frustrating experience of meaninglessness.

“Our generation has failed so utterly. So spectacularly.”

Bob Geldof

Bob Geldof

In a 2013 interview with Bob Harris on BBC Radio 2, Geldof reflected on his songs from that era, stating, “Tragically, what’s changed? I could have written those things, that way, yesterday. That’s terrible. Our generation has failed so utterly. So spectacularly.” While the societal issues Geldof addressed in his 70s and 80s songs may or may not have been resolvable, and while the tragic recurrence of mass violence is undeniably heartbreaking, “I Don’t Like Mondays” occupies a unique space.

The song’s enduring power lies in its acknowledgment of our shared capacity for irrational rage and feelings of meaninglessness, coupled with the unsettling recognition of our vulnerability to random acts of violence. While definitive answers or comforting resolutions may remain elusive, confronting this reality, this inherent senselessness, through art like “I Don’t Like Mondays,” becomes a meaningful act in itself. The questions raised by the song, unfortunately, are not bound by time; they remain part of the human condition, every day of the week.

Later Performances: The Song’s Evolving Life

“I Don’t Like Mondays” has become a staple in Bob Geldof’s performances with The Boomtown Rats. They performed it at The Secret Policeman’s Other Ball in 1981. The initial weariness Geldof expressed on The Merv Griffin Show just months earlier transforms into a more celebratory acknowledgment of the song’s impact. In this performance, he recognizes its significance to their career, yet the performance itself remains as much theatrical as purely musical.

The Boomtown Rats notably featured “I Don’t Like Mondays” as the opening song of their set at Live Aid in 1985, the monumental concert spearheaded by Geldof for famine relief in Africa. In the context of such earnest humanitarianism, a murder ballad might seem an incongruous choice, yet it was undeniably their most globally recognized song, ensuring immediate audience engagement.

Two decades later, at the Brit Music Awards, Geldof received a lifetime achievement award, with The Boomtown Rats performing “I Don’t Like Mondays” with symphonic accompaniment. While Geldof’s performance remains expressive, a discernible mellowing, a shift in tone, is evident.

Finally, a recent audience recording from the Isle of Wight Festival captures a contemporary iteration of the song. While audio quality is variable, it reveals the song’s continued power as a sing-along anthem for a new generation of listeners.