Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s most successful composition, “A Perfect Day,” stands as a testament to the unexpected power of music. Arguably one of the most significant overlooked songs of the 20th century, this gentle ballad, published in 1910, became an unlikely yet profound anthem during World War I. Years after its initial release, when its popularity might have been expected to wane, “A Perfect Day” resonated deeply with Allied troops and civilians alike, embedding itself into the cultural fabric of the United States and the British Empire. Outshining even patriotic tunes like George M. Cohan’s “Over There” and “It’s a Long, Long Way to Tipperary,” the poignant melody and heartfelt words of “The End of a Perfect Day,” as it was also known, offered solace and strength to soldiers on the front lines and their families back home.

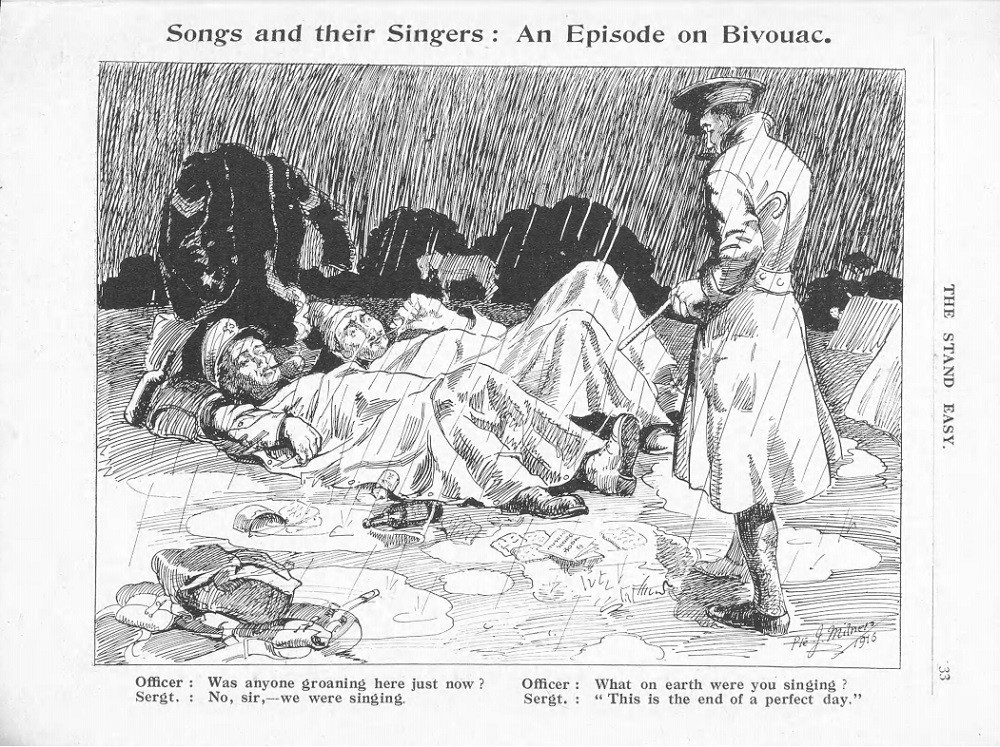

Cartoon depicting soldiers in a bivouac with the caption referencing "A Perfect Day".

Cartoon depicting soldiers in a bivouac with the caption referencing "A Perfect Day".

An Episode on the Bivouac, a 1916 cartoon by Private J. Milners, captures the song’s pervasive presence even in the harsh realities of war.

An Unlikely Wartime Hit

The surge in popularity of “A Perfect Day” is clearly reflected in its sheet music sales. Between February 1914 and January 1915, sales exceeded one million copies, demonstrating its rapid ascent. By the war’s end, over four million copies had been sold, further propelled by more than fifty recordings from renowned singers such as Frances Alda, Clara Butt, and Evan Williams. This phenomenal success far surpassed any other song of the era, solidifying its place as a cultural phenomenon.

Newspapers across the United States and Great Britain during the war years provide ample evidence of the song’s widespread appeal through reports of public performances. British press accounts from this period frequently mention “A Perfect Day” as a staple in concerts throughout the nation, often requested as a beloved encore. Remarkably, in November 1916 alone, newspapers documented 98 performances, followed by another 108 in December. These performances spanned diverse settings, from fundraising events and hospital concerts for wounded soldiers to church gatherings, particularly within Non-Conformist communities. During the summer months, a band arrangement featuring a solo trumpet became a popular fixture in park concerts, a tradition that continues in some places to this day.

The Emotional Resonance of a “Perfect Day” During Wartime

“A Perfect Day,” by Highley Colliery Brass Band, Bewdley, UK, 2015. Soloist Joe Hill.*

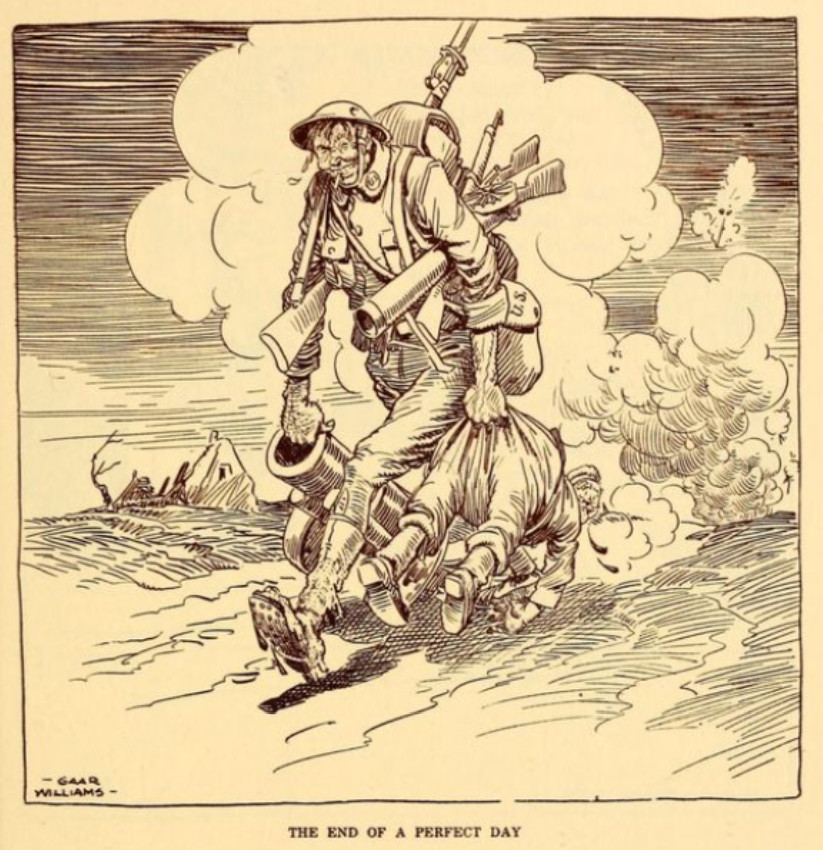

The song’s profound impact on soldiers stemmed from its ability to evoke powerful emotions and memories. For many, “A Perfect Day” served as a poignant reminder of home, a connection to loved ones, or a tribute to comrades lost in battle. It became a symbol of gratitude for survival amidst the daily dangers of war. In the post-war years, the song continued to resonate, serving as a somber reflection on fallen comrades buried in foreign cemeteries. The song’s title became deeply embedded in the cultural lexicon of the time, appearing as captions in numerous cartoons and inspiring artistic works, such as George Wotherspoon’s painting “The Close of a Perfect Day.” The nationally recognized cartoonist Gaar Williams also utilized the song’s title for his iconic image of a triumphant American soldier, which first appeared in the Indianapolis News on July 20, 1918, beneath the headline “Huns, Repulsed, Are Retiring Across the Marne.”

Cartoon of a triumphant doughboy with "The End of a Perfect Day" caption.

Cartoon of a triumphant doughboy with "The End of a Perfect Day" caption.

Left: George A. Wotherspoon’s painting, The Close of a Perfect Day, and Right: Gaar Williams’ cartoon, The End of a Perfect Day, exemplify the song’s cultural impact during and after WWI.

Understanding the Song’s Enduring Power

Contemporaries recognized and analyzed the sources of “A Perfect Day”‘s immense power even during the war. The song’s magic lay in the equal contribution of its melody and lyrics. The tune was easily hummed and whistled, while the words were frequently quoted and paraphrased in letters sent home. An article in the Australian newspaper The Adelaide Register in September 1918 eloquently captured these sentiments:

There are few concert programmes from which this song is absent, either at home or close to the front line. At one of the latter, during a pause in the sing-song, the leader … announces that he will sing a solo. “What do you want?” he asks. Some cry “The perfect day,” and others ask for another song. “Show hands,” he cries; there are a few dozen for one, and some hundreds for the other, so “The perfect day” is sung. It is always a prime favourite, and the psychology of the song is a study. It enables the man to think of home, but the spirit of the piece saves them from any dull feeling of loneliness; the heart is wreathed in good feeling, sober and subdued, and, as they think of the home folks, they have no dread; all is well there as with themselves. It is not a song they want to sing so much as listen to, and when it is sung to the piano, and the soft compelling notes of the violin, a hush falls, and they listen without moving a muscle.

The most meaningful responses for Carrie Jacobs-Bond were the numerous letters she received from soldiers expressing their heartfelt appreciation for “A Perfect Day.” One such letter from a soldier in England in July 1917 poignantly illustrates the song’s pervasive presence and profound impact:

In England, July 10, 1917 / Mrs. Carrie Jacobs-Bond: I have often thought of writing to you about the marvelous popularity of this particular song. I mean to be perfectly candid without the slightest intention of flattering you, when I say that ‘The End of a Perfect Day’ is the most popular ballad in the army of the Allies. I heard it last winter played upon a one-string violin accompanied by several quaky voices as it came from a quarantined hut; I heard a famous London singer at the Soldiers’ Recreation hut, where thousands were; I heard a cornetist, with a woefully bad band, puff and spout his way through it and receive a tremendous encore; I heard an entire battalion, coming in from the rifle ranges, sing this number as a marching song; I heard it as a duet Sunday night in a little old tent where divine services were held for such as might come. I have used the song dozens of times by request and have always found it to be enthusiastically received. / Very truly yours, Ed Chenette (Watt, 1917).

The song’s significance extended to groups like the “Shrapnel Quartet,” composed of four blind soldiers who had sustained injuries in battle. Touring the front lines to contribute to the war effort through music, they favored Carrie Jacobs-Bond’s songs in their repertoire. As one member wrote to Mrs. Bond, “‘Over here in the trenches and in the crowded hospital wards, we do not sing ‘There’ll Be a Hot Time in the Old Town Tonight,’ … we sing the song that has become the inspiration of the trenches: ‘The End of a Perfect Day’” (Anon., 1918). A 1914 recording by the Metropolitan Quartet offers a glimpse into the sound of soldier quartets performing the song.

A Lasting Legacy Beyond the Battlefield

Metropolitan Quartet, performing “A Perfect Day” in an Edison Blue Amberol recording from August 1914.

The phrase “the end of a perfect day,” popularized by the song, became synonymous with the conclusion of World War I celebrations. Eddie V. Rickenbacker, the renowned American fighter pilot, noted in his diary entry for November 10, 1918: “Report of Kaiser’s abdication and revolution in Germany. Indeed the end of a perfect day.” Carrie Jacobs-Bond recounted an anecdote shared by her son, Fred Smith, about witnessing an impromptu performance in Manhattan on Armistice Day, November 11, 1918:

On November 11th, 1918, the day the Armistice was signed, my son was in New York City, standing at the head of Central Park, when four men put their arms around each other’s waists and began marching and singing A Perfect Day. My son joined them and they gathered singing men until they landed down at Madison Square with over 5,000 in that serpentine line all singing my song. When my son telegraphed me this news I said, ‘This is the end of A Perfect Day for me’ (Bond, 584).

A postcard from summer 1918, visually representing the peaceful imagery associated with “A Perfect Day,” a stark contrast to the war context in which it gained immense popularity.

In conclusion, “A Perfect Day” transcended its origins as a simple ballad to become a powerful and enduring symbol of hope, memory, and shared humanity during and after World War I. Its unexpected journey to becoming a wartime anthem underscores the profound and often unforeseen ways in which music can deeply connect with human emotion and experience, offering solace in times of turmoil and lasting resonance across generations.

References

Anon., “Famous Woman Composer Sings at Syracuse,” Music Leader, vol. 36 no.16 (17 Oct. 1918), 381.

Carrie Jacobs-Bond, “Music Composition as a Field for Women. From an Interview Secured Expressly for The Etude, with the Most Successful Composer of Songs of the Present Day,” Etude Magazine (Sept. 1920), 583-84.

Charles Watt, “Carrie Jacobs-Bond: An Appreciation,” Music News, vol. 9 no. 4 (2 Nov. 1917), 20-21.

Australian War Memorial post on “A Perfect Day”.