Episode 136 of A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs delves into the iconic “My Generation” by The Who, a track that resonated with a generation and solidified the band’s place in rock history. This in-depth exploration examines the song’s creation, its cultural impact, and the fascinating story behind the band itself.

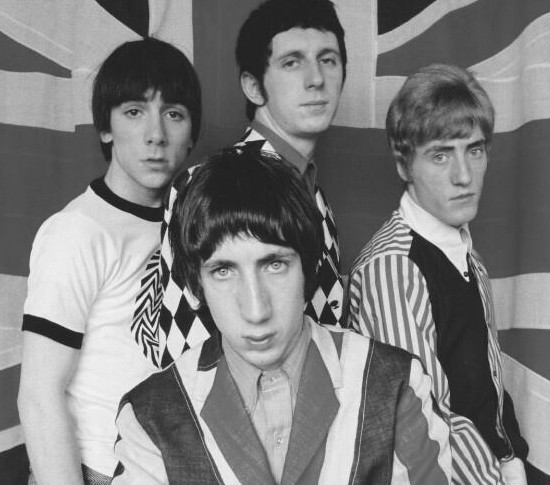

The Who, in front of a Union flag, in 1965

The Who, in front of a Union flag, in 1965

Generational Theory and the Sound of Youth

In 1991, William Strauss and Neil Howe introduced their generational theory in Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. Their work, though debated for its broad strokes, posited that generations share personality types shaped by formative events. This concept, while focused on America, has permeated Western thought, influencing how we perceive generational shifts and identities. While their predictions may not always be accurate, the framework of understanding history through generational lenses has become ingrained in popular culture.

Strauss and Howe identified several generational cohorts, including the “Greatest Generation,” “Silent Generation,” “Baby Boomers,” and “Millennials.” Notably, the generation born between the Boomers and Millennials, initially dubbed “Thirteeners,” became known as “Generation X,” a name borrowed from a late-1970s punk band fronted by Billy Idol.

Generation X, the band, directly engaged with the cultural landscape of their predecessors. Their song “Your Generation” was a clear nod to The Who’s anthem, highlighting the cyclical nature of generational dialogue in music. This dialogue is evident in their covers of songs by John Lennon and Johnny Kidd, and their original track “Ready Steady Go,” referencing the Mod-era TV show. Even their band name itself, Generation X, came from a 1964 book initially about the burgeoning Baby Boomer generation and the Mod vs. Rocker clashes in England.

Mods vs. Rockers: A Cultural Clash

The 1960s in Britain witnessed a vibrant youth culture clash between two distinct groups: the Rockers and the Mods. Rockers, reminiscent of American “greasers,” embraced a 1950s aesthetic influenced by figures like Marlon Brando and musicians like Gene Vincent. They represented a fading past. In contrast, the Mods were the embodiment of modernity, embracing sharp fashion, scooters, and a forward-looking attitude. This cultural battleground set the stage for the emergence of bands like The Who, who would become intrinsically linked with the Mod identity.

It was within this environment of generational and subcultural tension that “My Generation” was born, capturing the restless energy and defiant spirit of a new wave of youth.

Jim Marshall: From Performer to Amplifier Pioneer

The story of “My Generation” is intertwined with the story of Jim Marshall, whose amplifiers became crucial to The Who’s powerful sound. Marshall’s early life was marked by adversity. Diagnosed with skeletal tuberculosis at age five, he spent seven years in a full-body cast. This experience, paradoxically, fueled a passion for movement and music. He transitioned from tap-dancing to singing, eventually becoming a drummer out of necessity when his band’s drummer was drafted during World War II.

A crucial turning point came when Marshall, as a singing drummer, couldn’t hear the band over the PA system. This necessity drove him to build his own, louder amplification system. This DIY approach laid the foundation for Marshall Amplification, which would revolutionize rock music by providing the volume and power that bands like The Who needed to define their sound.

After a brief stint running a music shop, Marshall’s legacy was cemented when he began building and selling amplifiers. His shop became a hub for musicians, including Pete Townshend and John Entwistle, who sought out his equipment to achieve louder, more powerful sounds.

The Townshend Family: Musical Roots and Turbulent Upbringing

Pete Townshend’s musical journey began within a musical family. His father, Cliff Townshend, was a clarinetist and saxophonist who played with the Squadronaires. His mother was a singer. However, music was more of a profession than a passion in his household, and records were scarce. His early musical experiences were less about rock and roll and more about the sounds around him, including learning harmonica and the theme to “Dixon of Dock Green.”

His first exposure to rock and roll came through Ray Ellington, a British jazz singer influenced by Louis Jordan, who appeared on the Goon Show. While initially perceiving Ellington’s music as “hybrid jazz,” Townshend recognized a youthful rebelliousness in it, similar to the Goon Show itself.

A pivotal moment arrived when his father took him to see the film Rock Around the Clock. The energy of Bill Haley’s music ignited a passion in young Pete, marking a turning point in his musical trajectory. Despite his father’s initial acceptance of rock and roll due to its “swing,” the rise of the genre ultimately diminished the demand for his clarinet playing.

Townshend initially gravitated towards the saxophone, like his father, before switching to guitar and banjo. His early musical collaborations included joining a trad jazz band with John Entwistle, a friendship forged over a shared love of humor and Mad magazine.

John Entwistle: The Bass Pioneer

John Entwistle, later known as “The Ox,” became a crucial element of The Who’s sound with his innovative bass playing. Initially a trumpet player in trad jazz bands, Entwistle was captivated by Duane Eddy’s “twangy” guitar sound. Eddy’s use of the baritone guitar, or Danelectro bass, to create deep, resonant tones fascinated Entwistle.

Inspired by Eddy, Entwistle switched to bass, aiming to emulate Eddy’s style on his new instrument. He built his own bass guitar due to the prohibitive cost of electric basses in the UK at the time. His ambition was to make the bass a lead instrument, influenced by Eddy’s melodic approach.

Entwistle’s quest for a louder sound led him to Jim Marshall’s shop, where he purchased a cabinet with four 12-inch speakers. This pursuit of volume, mirroring Townshend’s, became a defining characteristic of The Who’s sonic identity.

The Detours and the Formation of The Who

Roger Daltrey, initially a guitarist leading the band Del Angelo and his Detours, recruited Entwistle after hearing he played bass. Entwistle, in turn, brought Pete Townshend into the fold, attracted by the promise of using a powerful amplifier owned by the band.

The early Detours were a cover band, playing Shadows hits and dabbling in trad jazz. However, a stylistic clash emerged between Daltrey, with his working-class background and conservative tastes, and Townshend, the art-school student with burgeoning intellectual and artistic ambitions.

Townshend’s exposure to art school and figures like Gustav Metzger, who championed auto-destructive art, began to influence his artistic vision. He also discovered jazz double-bass player Malcolm Cecil, who experimented with unconventional playing techniques, including instrument destruction. These influences, while initially subtle, would later manifest in The Who’s performances.

Volume and Power: Defining The Who’s Sound

The Detours, evolving into The Who, sought to increase their volume, partly to overpower hecklers in rowdy audiences. Townshend and Entwistle both acquired Marshall amplifiers, escalating a “volume war” that resulted in Townshend stacking two speaker cabinets – the birth of the Marshall stack.

This extreme amplification influenced Townshend’s guitar playing. He moved towards power chords, utilizing distortion and feedback to create a raw, powerful sound. Power chords, consisting of only the root and fifth notes, became a cornerstone of his style, contributing to the band’s signature sonic aggression.

Image and Identity: From Detours to The Who

Two key events shaped The Who’s early image. Supporting the Rolling Stones exposed Townshend to Keith Richards’ stage presence, inspiring the iconic “windmill” guitar move. Simultaneously, another band called Johnny Devlin and the Detours gained national attention, forcing Daltrey, Townshend, and Entwistle to rename their group. They settled on “The Who,” a name that resonated with a sense of questioning and identity.

Management and Mod Culture: Pete Meaden and The High Numbers

The Who’s early management by Helmut Gorden, a doorknob factory owner, was unconventional. Gorden lacked music industry experience but provided a salary and equipment funding. However, his contract was ultimately deemed invalid.

Pete Meaden, initially Gorden’s assistant, became a crucial figure in shaping The Who’s image and direction. Meaden, a Mod himself, steered the band towards a Mod aesthetic and rebranded them as The High Numbers, aligning them with Mod subculture terminology.

Meaden secured a single deal for The High Numbers, releasing “Zoot Suit” and “I’m the Face,” songs directly targeting the Mod audience. These songs, while drawing heavily from existing R&B tracks, failed to achieve commercial success. However, The High Numbers cultivated a strong live following within the Mod scene.

Townshend observed the dynamic of Mod culture, noting how trends and dance moves spread organically within the subculture. The band adapted, mirroring the audience’s evolving tastes and solidifying their connection with the Mod movement.

Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp: A Fortuitous Encounter

A pivotal moment arrived with the entrance of Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp. Lambert, son of composer Constant Lambert, and Stamp, brother of actor Terence Stamp, were aspiring filmmakers inspired by A Hard Day’s Night. They sought a band to document, aiming to capture a pop group’s rise to stardom in a nouvelle vague-style film.

They discovered The High Numbers at the Railway Hotel. While their film project, High Numbers, remained unfinished, Lambert and Stamp recognized the band’s potential and transitioned into management. They replaced Gorden and Meaden, taking over The Who’s trajectory.

Lambert and Stamp’s management was transformative. They encouraged the band’s explosive stage presence, including Townshend’s guitar smashing and Moon’s drum kit destruction, recognizing its performance value despite the financial cost.

Original Material and Musical Expansion

Early on, Decca Records rejected The Who due to a lack of original material. This prompted Townshend to focus on songwriting. His musical horizons broadened, encompassing influences beyond R&B, including Bob Dylan, John Lee Hooker, Charles Mingus, baroque music, and a range of jazz and soul artists.

Despite Daltrey’s initial resistance to straying from R&B, Townshend incorporated these diverse influences into his songwriting. The Who’s first single, “I Can’t Explain,” showcased a Kinks-inspired riff blended with Beach Boys-esque vocal harmonies, achieving top ten success.

Daltrey, however, remained committed to a harder R&B sound. The Who’s first album project leaned heavily into soul and R&B covers. For the second single, “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere,” Daltrey was given songwriting input, marking his only A-side writing credit with the band.

“My Generation”: From Demo to Anthem

Internal tensions within The Who escalated. Daltrey’s dissatisfaction with pop music and the other members’ drug use led to a confrontation and his temporary expulsion from the band. However, the rising chart success of their latest single, “My Generation,” compelled the band to reinstate him.

“My Generation” had a long and complex evolution. Initially inspired by Mose Allison’s “Young Man’s Blues,” Townshend’s demo was more blues-oriented. Lambert and Stamp encouraged a heavier guitar riff and key changes. Stamp also suggested accentuating a stuttering vocal delivery that Daltrey had adopted, inspired by Sonny Boy Williamson II.

The stutter became a defining feature of “My Generation,” operating on multiple levels. It reflected the theme of youthful inarticulacy, resonated with the Mod subculture’s amphetamine use (which could induce stuttering), and hinted at rebellious sentiments that couldn’t be explicitly stated on the radio.

Innovations in “My Generation”: Bass Solo and Cacophony

“My Generation” broke ground with its prominent bass solo by John Entwistle. While not the first bass solo in rock, it was unusually featured and showcased Entwistle’s virtuosity. Recorded on a Fender Jazz bass after Danelectro string breakages, the solo became a landmark moment for the instrument in rock music.

The song’s outro was equally revolutionary, culminating in a chaotic explosion of feedback and drums, a sound previously confined to live performances. This cacophony captured the raw energy and rebellious spirit of the song.

Legacy of a Generational Anthem

“My Generation” became The Who’s biggest hit to date in the UK, reaching number two. Although less successful in the US initially, the song’s impact resonated across generations. It cemented The Who’s status as a defining band of the 1960s and established Pete Townshend as the band’s primary creative force.

“My Generation” remains a powerful anthem, capturing the frustrations, aspirations, and defiant energy of youth. Its innovative musical elements and culturally resonant lyrics ensured its place as a timeless rock classic and a defining “My Generation Song.”

Discover more from A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.