The other night, while randomly browsing, Death Race 2000 popped up, and I decided to give this 1975 cult classic a watch. Starring David Carradine as Frankenstein and a young Sylvester Stallone, it was a bizarrely enjoyable low-budget, post-apocalyptic satire centered around deadly car races. Carradine, excellent in his role, was actually cast because Peter Fonda wasn’t available. This movie was intended to elevate Carradine’s career beyond his then-famous role as Kwai Chang Caine, the Shaolin monk in ABC’s Kung Fu series. This series, starting in 1972, coincided perfectly with North America’s explosive fascination with kung fu, karate, judo, jiu-jitsu, and ninjas.

David Carradine as Kwai Chang Caine in Kung Fu TV series

David Carradine as Kwai Chang Caine in Kung Fu TV series

This martial arts craze can largely be attributed to Bruce Lee. While not initially through his movies, Lee first captured American attention as Kato in the 1966 Green Hornet TV series. Playing Britt Reid’s valet who was also a martial arts expert sidekick, Lee insisted on showcasing his authentic skills, which went beyond typical TV fight choreography. This marked the beginning of a cultural phenomenon.

Carradine’s Kung Fu series further fueled this fire from 1972 to 1975. By 1973, the craze was undeniable. The movie Five Fingers of Death, released in March 1973, surprisingly surpassed The Poseidon Adventure to become America’s top film. Over 30 kung fu genre movies flooded US theaters by the end of that year. Western audiences were drawn to these films for their themes of lone heroism and action-packed violence. However, there was also a novel appeal – the allure of ancient art forms, exotic cultures, intense discipline, rigorous training, and hierarchical structures.

Born in 1973 myself, kung fu movies, especially those featuring Bruce Lee and Shaw Brothers productions, were a significant part of my childhood. The advent of VCRs and movie rentals meant a constant stream of these films into our homes. Even Miss Piggy on The Muppet Show adopted a karate chop, replacing a slap as her signature reprimand, a change driven by Frank Oz finding chopping easier for the puppet.

Elvis Presley in his Karate era

Elvis Presley in his Karate era

Inevitably, the kung fu craze infiltrated popular music. Elvis Presley‘s introduction to karate dates back to his time in the U.S. Army in 1958, stationed in Germany. He earned a black belt by 1960, and by 1969, karate moves became integrated into his stage performances, and had been a staple in his movie fight scenes since 1961. While Peter Sellers’ Inspector Clouseau comically trained with his servant Kato in the 1964 film A Shot In The Dark, and humorously claimed his hands were “lethal weapons,” Elvis seems to be the first Western music icon to genuinely incorporate martial arts into his public persona and performance style.

Presley is just one of many musicians with a serious interest in martial arts. The roster includes Willie Nelson (Gong Kwon Yusul), Joan Baez (Aikido), Mick Jagger (Judo), Glenn Danzig and David Lee Roth (Jeet Kune Do), Dave Mustaine, Ice-T, and Tommy Lee (Brazilian Jiu Jitsu).

Despite his karate influence, Elvis never actually recorded a kung fu or karate-themed song, contrary to what some might think. The song they are likely misattributing to him is Carl Douglas’s massive 1974 disco hit, Kung Fu Fighting. Douglas, a Jamaican-born British singer and former engineering student, had been releasing R&B singles in the 60s. Kung Fu Fighting was initially conceived and recorded in a mere ten minutes as the B-side to “I Want To Give You Everything.” However, it quickly became apparent to the record label and the world that Kung Fu Fighting was the true hit.

The song, Kung Fu Fighting, became an instant earworm, achieving global recognition. It has been remixed, covered, re-recorded, and re-released countless times, yet none have surpassed the original’s phenomenal sales of 11 million copies. It’s undeniably one of the biggest hits of all time.

The song’s iconic opening “whoa ho ho ho!” and the stereotypical nine-note musical phrase, often used to denote Asian themes, are instantly recognizable. However, it’s impossible to ignore the song’s problematic elements, especially when viewed through a modern lens. Lyrics containing phrases like “funky Chinamen” are overtly racist by today’s standards.

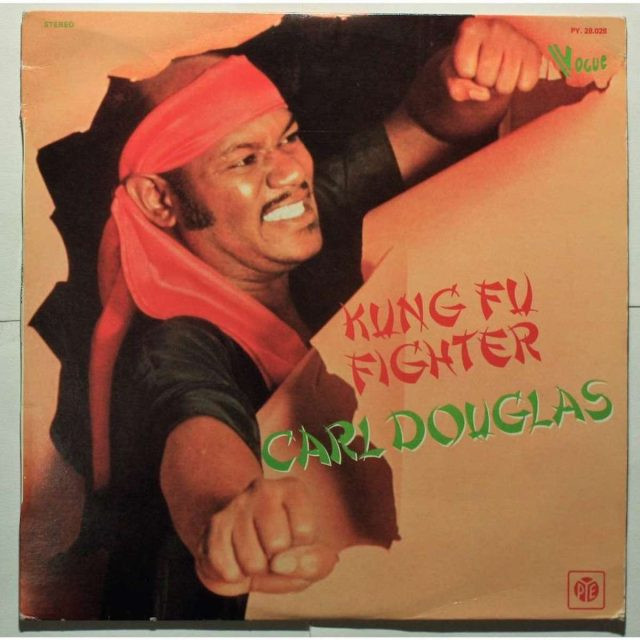

Following the single’s massive success, Douglas released the album Kung Fu Fighter in 1974. It featured the original intended A-side, alongside another kung fu-themed disco track, “Dance The Kung Fu.” It seemed Carl Douglas and producer Biddu were keen to capitalize on the kung fu craze as much as possible. Interestingly, it was Biddu himself who provided the fighting grunts featured in Kung Fu Fighting.

While perhaps not as commercially impactful as Kung Fu Fighting, Lalo Schifrin’s theme from the 1973 Bruce Lee blockbuster Enter The Dragon is another notable kung fu-inspired musical piece. This, Lee’s final film, is packed with classic kung fu movie elements: funky wah-wah guitar, Chinese musical motifs, and Lee’s signature fighting cries. Schifrin, renowned for his scores for Mannix, Mission: Impossible, Bullitt, Dirty Harry, and Starsky & Hutch, brought his signature funky style to the genre.

Another less commercially successful but noteworthy track is Blondie’s 1976 song “Kung Fu Girls” from their debut album. This song tells a story of a man outsmarted and robbed by a group of street-savvy, kung fu-skilled young women.

However, for true dedication to kung fu themes in music, hip-hop pioneers Wu-Tang Clan stand unmatched. Growing up on Staten Island immersed in 70s kung fu films, these founding members were deeply influenced by the genre. The group’s name itself originates from the 1983 movie Shaolin and Wu-Tang!, and they famously rebranded Staten Island as “Shaolin” in their lyrics. Their music is rich with samples and references from numerous Shaw Brothers films. RZA, a key member, is practically an expert on the intersection of kung fu cinema and hip-hop culture.

In conclusion, the “Kung Fu Fighting Song” by Carl Douglas became a defining sound of the 70s craze, but it is just one piece of a larger cultural phenomenon where martial arts and music intersected in fascinating and sometimes problematic ways. From Bruce Lee’s initial spark to the lasting impact on genres like hip-hop, the kung fu craze left an indelible mark on popular culture, and its echoes can still be heard today.