Freddie Palmer with the McIntosh County Shouters performing “Kumbaya” at the Library of Congress in 2010. Explore their full concert through the provided link. Photo credit: Stephen Winick.

In celebration of African American History Month, we delve into the captivating history of “Kumbaya,” a spiritual song also known under variations like “Kum Ba Yah,” “Come By Yuh,” and “Come By Here.” Since its initial scholarly exploration, new insights have emerged, notably Dr. Griffin Lotson’s successful endeavor to recognize the song as Georgia’s official State Historical Song. The historical context presented to the Georgia State Legislature, culminating in a Senate resolution in February 2017, drew significantly from earlier research into this deeply resonant song.

Publicity photograph of Odetta from 1958, John Ross photographer. Sourced from the Library of Congress, New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection. [hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3c15394]

“Kumbaya,” once a cornerstone of the folk revival movement, has experienced a complex journey in public perception. From the 1950s through the 1990s, it flourished, embraced by iconic artists such as Joan Baez, The Weavers, Odetta, Pete Seeger, Sweet Honey in the Rock, and international voices like Joan Orleans and The Seekers. However, from the 1980s into the 2000s, a shift occurred. Musically, it became relegated to children’s campfire sing-alongs, deemed too simplistic for adult engagement. Politically, it became a symbol of ineffective, superficial attempts at unity. Socially, it acquired connotations of being overly sentimental, naive, and lacking substance. These contemporary views unfortunately overshadow the song’s origins as a beautiful and authentic piece of traditional music, rich in dialect and creativity. Despite this shift, the song’s evolving image has contributed some vivid expressions to American political language, such as “joining hands and singing ‘Kumbaya'” to signify ignoring fundamental differences for superficial harmony, and “Kumbaya moment” to describe events characterized by such shallow unity. (Further reading on this semantic shift is available in this article.)

Regardless of its shifting cultural meanings, the fundamental question of “Kumbaya’s” origin remains a point of scholarly interest: Where and when did this song first emerge? The American Folklife Center Archive at the Library of Congress stands as the premier resource for answering this question. The Archive meticulously documents the song’s early history, housing the earliest known sound recordings and likely the oldest manuscript version. Furthermore, the Archive’s subject file dedicated to “Kum Ba Yah” contains invaluable historical documents. Researchers, notably Chee Hoo Lum, have utilized these resources to piece together the song’s narrative. (Lum’s research is published in Kodaly Envoy, 33(3): pp5-11.)

Recent discoveries within the AFC—a manuscript from 1926 and a cylinder recording from the same year—provide a more comprehensive understanding and challenge common misconceptions surrounding the song. One prevalent misconception, perpetuated by the song’s initial resurgence during the folk revival, claimed African origins. The first revival recording, “Kum Ba Yah” by The Folk-smiths in 1958, asserted African roots in its liner notes, citing unsubstantiated claims of missionary collection in Angola. Conversely, some scholars proposed Anglo-American evangelist Marvin Frey as the originator. Frey published and copyrighted sheet music for “Come by Here” in 1939, later claiming authorship, a view echoed by publications like the New York Times (see obituary). Thus, early folk revival discourse presented two dominant origin theories: African and white American authorship. Both theories, however, are challenged by the AFC’s newly examined early documents.

Currently, the most widespread theory attributes “Kumbaya” to the Gullah-Geechee people of coastal Georgia and South Carolina. (More exaggerated versions, as seen on a 2010 Wikipedia entry, even suggest Aramaic roots for “Yah,” despite “yah” simply meaning “here” in Gullah.) While a Gullah origin is plausible and closer to the truth than previous theories, the AFC’s archival findings introduce complexities to this claim as well.

The Boyd Manuscript: An Early Written Record of Kumbaya

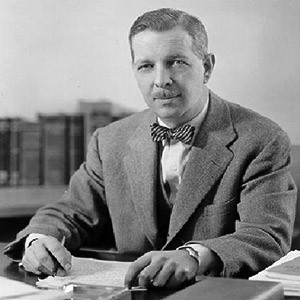

Portrait of Julian Parks Boyd. Image courtesy of AFC Subject Files.

Among the earliest documents in the AFC archive related to “Kumbaya” is a manuscript received by Robert Winslow Gordon, the archive’s founder, in 1927. Submitted by Julian Parks Boyd, then a high school principal in Alliance, North Carolina, this manuscript contains a version of the song collected from his student, Minnie Lee, in 1926. Titled “Oh, Lord, Won’t You Come By Here,” mirroring the song’s refrain, Lee’s version features single-line verses repeated thrice, followed by the refrain. Examples include: “Somebody’s sick, Lord, come by here,” “Somebody’s dying, Lord, come by here,” and “Somebody’s in trouble, Lord, come by here.” This structure firmly establishes Lee’s rendition as an early form of the now-famous “Kumbaya.”

Minnie Lee’s “Kumbaya” connects to the intriguing story of Julian Parks Boyd, a figure unearthed within the AFC archive. Boyd, holding a master’s degree from Duke University (1926), spent a brief year (1926-1927) teaching in Alliance, North Carolina. During this time, he displayed a remarkable passion for folksong. Letters to Gordon (also preserved in the AFC archive) reveal Boyd’s traditional folklore collection method: tasking students with gathering songs from their communities. Despite selective curation, Boyd amassed over a hundred songs, compiled into a typed manuscript. Learning of Gordon through his Adventure magazine columns, Boyd sought his guidance, sending the manuscript in February 1927.

However, by March, Boyd’s folksong collecting faced resistance, contributing to his decision to pursue graduate studies. “The school board and the community in general seem to think that [collecting folksongs] is an obnoxious practice, for some uncertain reason. The seniors were righteously indignant—it was the one thing that had thoroughly aroused their interest,” he wrote to Gordon on March 30th. He humorously described the school board as “long, wooden, and narrow,” explaining his move to the University of Pennsylvania for doctoral studies.

Boyd’s transition to the University of Pennsylvania marked the end of his active folksong collecting but launched a distinguished career in history and librarianship. He served as Head Librarian and History Professor at Princeton University, founding treasurer of the Society of American Archivists, and president of both the American Historical Association (1964) (Presidential Address Link) and the American Philosophical Society (1973-1976). His historical legacy is primarily as the editor of the definitive edition of Thomas Jefferson’s papers (Project History Link). (Read more in his ANB biography.)

Before fully embracing history, Boyd briefly returned to folklore. In his March 30th letter, he mentioned summer fieldwork in the Outer Banks, sponsored by Professor Frank C. Brown of Duke University, then president of the North Carolina Folklore Society. While correspondence with Gordon ends before the trip, its likely execution is supported by Boyd’s contributions to the Society’s collection, later published as the seven-volume Frank C. Brown Collection of North Carolina Folklore (LCCN Link). This collection includes Boyd’s version of “Kumbaya,” titled “Oh, Lord, Won’t You Come By Here,” often overlooked by scholars due to its title variation.

Boyd sent his manuscript collection to Gordon in Georgia, before Gordon established the Archive of American Folk-Song in Washington, D.C., now the American Folklife Center archive. Gordon brought the manuscript to Washington, among the archive’s initial holdings in 1928. Thus, “Kumbaya” was present in the Archive from its very beginning.

Cylinder Recordings: Hearing “Kumbaya” in 1926

Robert Winslow Gordon, the pioneering head of the Archive of American Folk-Song, pictured around 1930 with cylinder recordings and recording equipment at the Library of Congress.

Beyond the Boyd manuscript, the AFC Archive’s initial materials surprisingly included a sound recording of “Kumbaya,” a fact only recently确证. Among these original materials were four cylinder recordings of spirituals with the “come by here” or “come by yuh” refrain, collected by Gordon in Georgia between 1926 and 1928. Gordon recognized their connection, cross-referencing them in his manuscript and cylinder card catalog. Though two cylinders were subsequently lost or broken, two remained. However, the content of these cylinders needed verification to confirm if they were versions of “Kumbaya.”

One cylinder, transcribed by AFC staff member Todd Harvey and featured in Chee Hoo Lum’s 2007 article, is clearly not “Kumbaya.” Titled “Daniel in the Lion’s Den,” it’s a narrative spiritual with the “Come by Here” refrain, interesting for “Kumbaya” research but not a direct version of the song. Its verses are:

(1) Daniel in the lion’s den (2) Daniel [went to?] God in prayer (3) The Angel locked the lion’s jaw (4) Daniel [took a deep night’s rest?] (5) Lord, I am worthy now (6) Lordy won’t you come by here

Lum included “Daniel in the Lion’s Den” as the earliest recording Gordon linked to “Come by Here,” but surprisingly omitted analysis of the second surviving cylinder, instead using a 1936 John Lomax transcription. This omission is unfortunate, as the second cylinder, despite an inaudible section, contains audible verses at the beginning and end, definitively identifying it as “Kumbaya.”

This cylinder is, to our knowledge, the earliest sound recording of “Kumbaya,” making it crucial evidence in understanding the song’s early history. Listen to and download it here or via the player below!

{mediaObjectId:'CEA2B42FACA40108E0438C93F0280108',metadata:["Come by Here | Sung by H. Wylie. Recorded by Robert Winslow Gordon in 1926This is the first known recording of 'Come by Here,' a song that came to be known as 'Kumbaya.'Sung in ‘Gullah,’ or Sea Islands Creole Dialect."],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

Information about this cylinder is limited, but we know:

Robert W. Gordon’s catalog card for H. Wylie’s “Come By Here” recording.

- The song is “Come By Here.”

- The singer is H. Wylie.

- The location is unspecified, but likely near Darien, Georgia, where Gordon resided and primarily collected.

- Cylinder number A389, “Georgia 156.”

- Undated, but within Gordon’s system, items A290-A434 are from April 1926, suggesting a recording date within April 15th – May 3rd.

- The cylinder itself confirms this, with Gordon faintly stating at the end: “Sung by Henry Wylie, Darien, Georgia, April the seventeenth….”

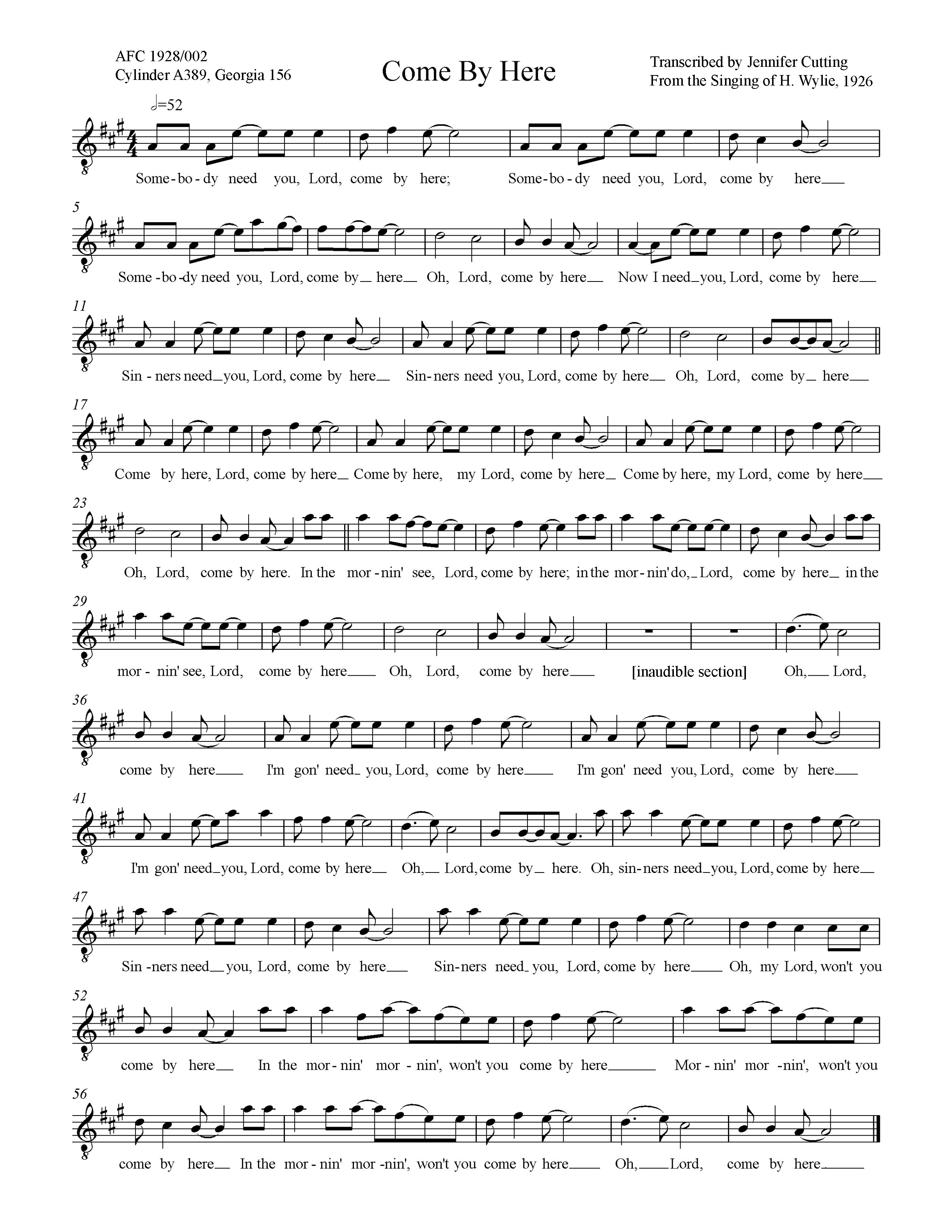

The lyrics and music are transcribed below (lyrics transcribed by the author, music by Jennifer Cutting):

Music transcription of “Come By Here” by Jennifer Cutting. Click to enlarge.

. . need you Lord, come by here,

Somebody need you, Lord, come by here,

Somebody need you, Lord, come by here,

|Oh, Lord, come by here.Now I need you, Lord , come by here

Sinners need you, Lord, come by here

Sinners need you, Lord, come by here

Oh, Lord, come by here.Come by here, Lord, come by here

Come by here, my Lord, come by here

Come by here, my Lord, come by here

Oh, Lord, come by here.In the morning see Lord, come by here

In the morning do Lord, come by here

In the morning see Lord, come by here

Oh, Lord, come by here.[inaudible section]

Oh, Lord , come by here.

I’m gon’ need you, Lord, come by here

I’m gon’ need you , Lord, come by here

I’m gon’ need you, Lord, come by here

Oh, Lord , come by here.Oh , sinners need you, Lord, come by here

Sinners need you, Lord, come by here

Sinners need you, Lord, come by here

Oh, my Lord, won’t you come by hereIn the mornin’ mornin’, won’t you come by here

Mornin’ mornin’, won’t you come by here

In the mornin’ mornin’, won’t you come by here

Oh, Lord, come by here.

AFC researcher Chris Smith uncovered more about H. Wylie. Wylie’s recordings appear alongside those of Jeff Union, recorded on April 17, 1926, at W.T. Marlow’s camp in Darien, suggesting Wylie was recorded at the same location.

Henry Wylly’s draft card, discovered by Chris Smith, potentially identifies the singer of “Come By Here” for Robert W. Gordon in 1926.

Smith’s research into draft and census records revealed details about Wylie:

Henry Wylly, born September 26, 1899, registered for the draft September 12, 1918, identified as ‘negro,’ and marked rather than signed. He was a boat hand in Crescent, McIntosh County, married to Felia Wylly, living in Eulonia, McIntosh County. The 1920 census lists a ‘mulatto,’ widowed, 20-year-old Henry Wylly as a convict in Darien county jail. Darien is McIntosh County’s seat. It’s unclear if this is the same Henry A. Wiley sentenced to life for murder in McIntosh County, incarcerated July 22, 1919, escaped July 26, 1926, with a ticked ‘Recaptured’ column entry, undated.

Publications from Wylie’s era highlight the song’s reach. In 1926, Madelyn Sheppard published “Oh, Lordy Won’t You Come By Here.” Sheppard, later of the Sheppard and Burns songwriting duo, was notable for being a white woman from Selma, Alabama, who composed blues and spirituals in African American dialect for African American publishers like W.C. Handy. Sheppard’s song isn’t “Kumbaya,” but its emergence alongside early “Kumbaya” versions indicates familiarity with the traditional song.

In 1931, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals published “Come by Yuh” in The Carolina Low Country (HathiTrust Link). Collected between 1922 and 1931, its exact collection date is unknown, making it difficult to definitively place it chronologically against Gordon’s materials. This version has the refrain “Come By Yuh, Lord, come by yuh,” and the verse “somebody need you lord, come by yuh,” echoing Gordon’s cylinder titles and the song we know as “Kumbaya.” By 1931, the song was documented from at least five singers, with related songs also emerging.

In 1936, John Lomax recorded another “Come by Here” version, sung by Ethel Best of Raiford, Florida. Verses were single lines repeated thrice, followed by “oh, Lord, come by here.”

(1) Come by here, my lord, come by here (2) Well we [down in?] trouble, Lord, come by here (3) Well, it’s somebody needs you lord, come by here (4) Come by here, my lord, come by here (5) Well it’s somebody sick Lord come by here (6) Well, we need you Jesus Lord to come by here (7) Come by here, my lord, come by here (8) Somebody moanin’, Lord, come by here

Listen to and download Ethel Best’s version here, or via the player below!

{mediaObjectId:'CEA2B42FACA60108E0438C93F0280108',metadata:["Come by Here | Sung by Ethel Best in Raiford, Florida, 1936. Recorded by John A. LomaxThis song came to be known as 'Kumbaya.'The chorus singing with Best is unidentified."],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

The Archive recorded more versions in Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas in the late 1930s and early 1940s.

Reassessing the Origins of Kumbaya: New Evidence and Old Theories

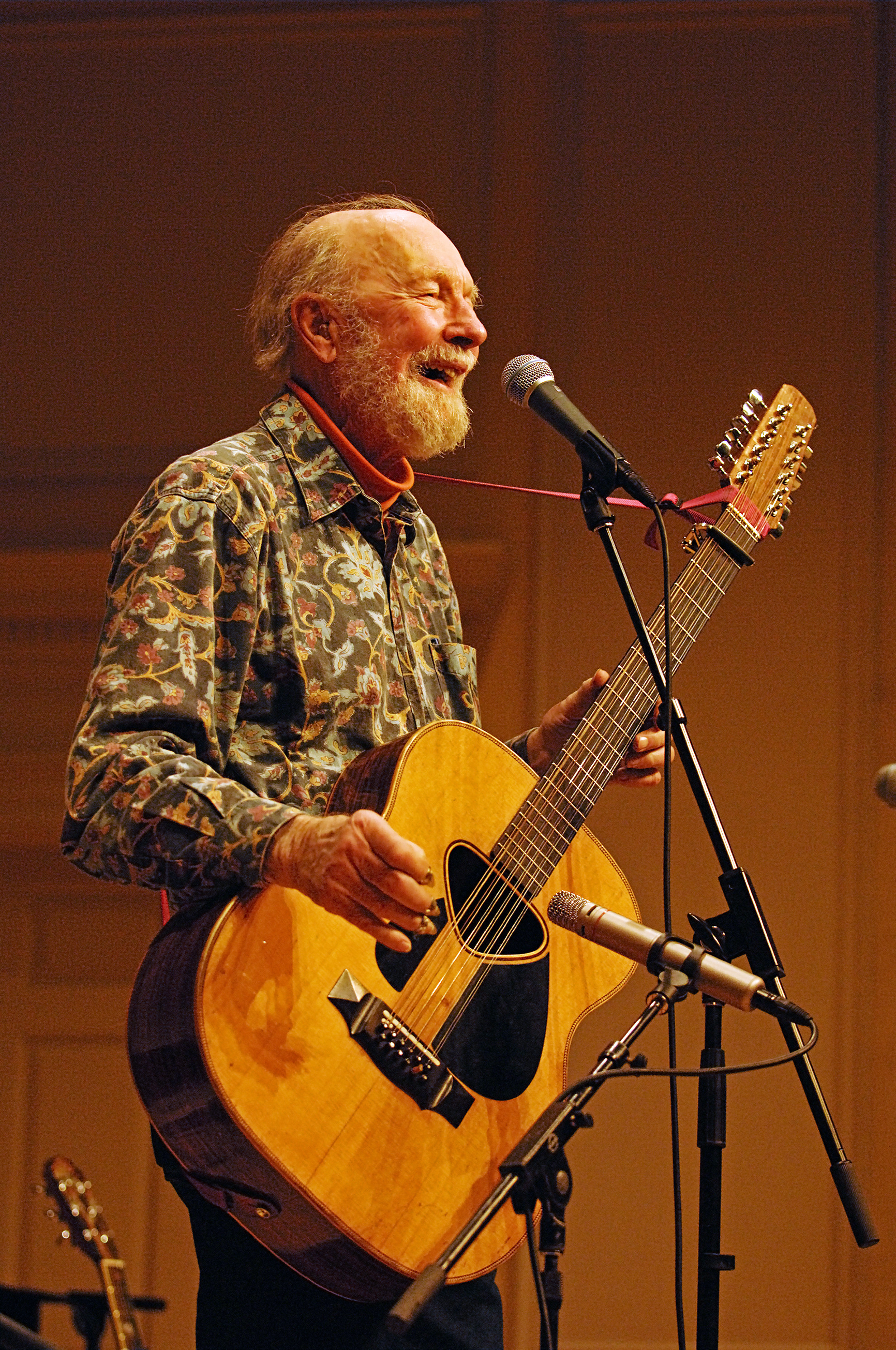

Pete Seeger, a key figure in popularizing “Kumbaya,” photographed at the Library of Congress in 2007. Photo by Robert Corwin, AFC Robert Corwin Collection.

By the 1940s, “Come By Here” was demonstrably a widespread spiritual among African Americans in the South. Yet, as mentioned, Marvin V. Frey (1918-1992), a New York City songwriter and evangelist, has often been credited with its 1936 composition, primarily due to his own claims. Frey copyrighted and published “Come By Here” in 1939, asserting authorship, stating he wrote the words in 1936 based on an Oregon evangelist’s prayer. This evangelist might have been adapting a pre-existing, widely known song. The question remains: how original was Frey’s “Come By Here”?

Chee-Hoo Lum’s research attempted to address this, but by focusing on the 1936 Lomax recording and overlooking the 1926 Wylie cylinder, Lum missed comparing Frey’s song with an earlier, more relevant version. Lum found the 1931 Carolina Low Country publication insufficiently similar to Frey’s version to confirm Frey’s reliance on tradition, thus considering Frey’s claim the “first possible ‘origin’ theory.” However, Wylie’s 1926 version, predating Frey’s by a decade and preserved in the AFC archive, is remarkably closer to Frey’s in both lyrics and melody. Wylie’s recording significantly weakens Frey’s claim of original composition based solely on a spoken prayer, rather than an existing song.

Further undermining Frey’s claim is the question of linguistic transformation. How did a Standard English song, “Come By Here,” become “Kum Ba Yah” or “Kumbaya” in oral tradition? Frey attempted to explain this through a story shared with Peter Blood-Patterson (archived at AFC in the “Kum Ba Yah” subject file, 1993):

While leading children’s meetings at a camp meeting in Centralia, Washington (1938), a young convert, Robert Cunningham, enthusiastically sang “Come by Here.” Cunningham’s missionary family later sang it in Detroit (1948), first in English, then in an “African dialect,” with “KUM BA YAH,” African drums, and bongos. Frey later claimed this dialect was Luvale, spoken in Angola and Zaire, suggesting “Kum Ba Yah” originated from a Luvale translation.

This explanation is problematic. “Come by Here” wouldn’t naturally translate to “Kum Ba Yah” in Luvale. “Kum Ba Yah” suggests a creole language with English influence, uncommon in 1930s Angola (Portuguese colony) or Zaire (Belgian colony, French-dominant). Crucially, the AFC’s Wylie cylinder provides a simpler explanation. Wylie’s dialect, likely Gullah, pronounces “here” as “yah,” making “come by here” sound like “come by yah,” phonetically close to “Kum Ba Yah” or “Kumbaya.”

A marker near Marvin V. Frey’s grave in West Barre Cemetery, New York, perpetuates his authorship claim to “Kum Ba Yah.” Photo by Michael Reese, used with permission.

If Frey’s authorship claim is weakened by the cylinder recording, so is the African origin theory. This theory stemmed from Lynn and Katherine Rohrbough, songbook publishers through the Cooperative Recreation Service of Ohio (AFC Rohrbough Collection Link).

The Folksmiths’ liner notes state the Rohrboughs learned the song from an Ohio professor who heard it from an African missionary. No date is provided, and the African origin claim seems based on “Kum Ba Yah” sounding “vaguely African” and the Rohrboughs’ unawareness of earlier American versions. Frey’s interview with Blood-Patterson suggests the Rohrboughs later conceded Frey’s authorship, indicating their limited confidence in the African origin theory. The AFC cylinder, with its “Kum Ba Yah”-like pronunciation, further diminishes evidence for an African origin.

The Folksmiths, circa 1957, made the first folk revival recording of “Kumbaya.” Photo courtesy of Joe Hickerson.

Finally, the Gullah Geechee origin theory remains plausible but is complicated by the Boyd manuscript. Without Boyd’s manuscript, AFC recordings suggested “Come by Here” was known early in the South, including Georgia and South Carolina, areas with Gullah presence. The Carolina Low Country transcription further reinforced this. This led scholars to favor a Gullah Geechee origin. However, Boyd’s manuscript from Alliance, North Carolina, outside Gullah territory, suggests the song circulated beyond Gullah regions from its earliest documentation. While a Gullah Geechee origin remains possible, it’s less certain the song originated specifically in Gullah, rather than broader African American English dialects. Gullah Geechee versions likely contributed to its later popularity.

In conclusion, the American Folklife Center Archive’s evidence doesn’t fully support any single dominant “Kumbaya” origin theory. Instead, it suggests “Kumbaya” is an African American spiritual, originating somewhere in the American South, spreading globally: to Africa via missionaries, to the Northwestern US where Frey adapted it, and within the Gullah Geechee coast. Gullah Geechee versions likely facilitated its entry into the Northeast, influencing singers like Pete Seeger and Joan Baez, and its subsequent global dissemination through folk revival recordings. While now a global folksong, its earliest forms are uniquely preserved in the AFC Archive.

Coda: Kumbaya’s Journey Through the Archive and into the Folk Revival

Poster for The Folksmiths, 1957. Courtesy of Joe Hickerson.

“Kumbaya’s” adoption into the folk revival also connects to the American Folklife Center Archive. Its popularization followed publication by the Rohrboughs. In 1957, Tony Saletan learned it from them and taught it to The Folksmiths, an Oberlin College group. The Folksmiths toured summer camps in 1957, teaching “Kumbaya” (as “Kum Ba Yah”) to thousands of campers, solidifying its association with children and campfires. They recorded it in August 1957 on We’ve Got Some Singing to Do (Folkways, 1958), the first published recording. Pete Seeger released his version later in 1958, titled “Kum Ba Ya.” In 1959, The Weavers (Seeger’s group) recorded it as “Kumbaya.” The title transformation from “Come by Here/Come by Yah” to “Kumbaya” was complete.

Later folk revival versions largely stem from these influential recordings, all linked to the AFC Archive. Seeger interned at the Archive in the 1930s and revisited many times, recalling hearing Gordon’s “Come by Here” cylinder there. Joe Hickerson of The Folksmiths became a folklorist and archivist, eventually heading the AFC Archive until 1998. The story of “Kumbaya” demonstrates a powerful link: while “Kumbaya” spread from the AFC Archive, the Archive remains deeply embedded within “Kumbaya’s” story.