Colson Whitehead’s novel John Henry Days is not just a story; it’s a symphony of voices, each echoing and reinterpreting the quintessential American folk ballad, the John Henry Song. The novel itself functions as a continuous “re-singing” of this iconic tune, delving into its depths and revealing its multifaceted nature. By examining how John Henry Days constantly revisits and reimagines the song of the steel-driving man, we uncover the song’s vastness and how each rendition reflects a different facet of the American experience itself.

One way to understand the novel’s approach to the John Henry song is to consider the image of “The Lone Songwriter,” or “The Guy on the Hill.” This figure, introduced early in the original lecture, embodies the genesis of folk music—an individual, musing and singing aloud, absorbing the world around them. He’s told, “there’s a whole country of songs out there,” realizing the fluid, ever-changing nature of musical tradition, how “like a dollar bill, a song changes hands.” This solitary singer, almost “stealing the song today,” becomes a hidden presence throughout John Henry Days, his voice fracturing and multiplying into the diverse characters and narratives that populate the novel.

In John Henry Days, the John Henry song is not static; it’s a living, breathing entity, constantly being reshaped and reinterpreted by various “singers.” Jake Rose, a song plugger in 1905 New York City, exemplifies one such voice. Recruited from a synagogue choir, Rose dreams of writing songs, working in a bustling, competitive environment where “newspapers in pianos” are used to muffle sound and prevent song theft. We encounter him in a vulnerable state, “lying in the snow after having been beaten and robbed,” a stark image of the often harsh realities of the music industry even in its nascent stages.

[Read pp. 204-05 from the original text, which details Jake Rose’s song writing process and the competitive environment.]

This scene showcases one “singing” of the John Henry song: the act of writing it down, adapting it to sheet music, making it commercially viable. Rose’s version is then further re-sung when performed by a nightclub singer. Whitehead draws a literal parallel to John Henry here: “Some places got music machines, player pianos that play songs that are already set, and there’s no use for a plugger when they got a machine to do it.” (203). This highlights the tension between human creativity and mechanical reproduction, a theme central to the John Henry legend itself. But Whitehead’s narrative goes beyond a simple retelling. Constructed from “bits and pieces of New York Public Library research,” the story of Jake Rose and the song takes on its own vibrant, independent existence, mirroring the organic growth of folklore.

The remarkable ten-page, single-paragraph chapter dedicated to Jake Rose raises a crucial question about the act of capturing the John Henry song on paper: “Is getting the song down on paper a race against time, against death, against memory, against forgetting?” This frantic, unbroken prose style itself embodies the urgency of preserving a fleeting cultural artifact. The piece of sheet music bearing Rose’s name becomes a recurring motif throughout the novel, a tangible symbol of the song’s enduring presence and its journey through different hands and times.

Moving forward in time and place, we encounter Moses, a Mississippi blues singer in 1930s Chicago. Moses is another voice “singing” the John Henry song, albeit indirectly. He’s accompanied by a young white man, a record producer figure, who attempts to dictate Moses’s music, embodying the commercial pressures and cultural appropriation prevalent in the music industry of that era. However, the “Lone Songmaker” spirit intervenes, urging Moses to “find his own song,” to tap into his authentic voice. As Moses begins to play, the lyrics “nothing but a man” spark a profound connection to the essence of the John Henry story.

“The words ‘nothing but a man’ set him thinking on it: Moses felt the natural thing–” and it’s interesting, Whitehead’s choice of “natural” for Moses—the song moves toward inevitabilities, commonplaces, what anyone would feel, what everyone would feel—

“–the natural thing would be to sing about what the man felt waking up in his bed the day of the race. Knowing what he had to do and knowing that it was his last sunrise… Moses could relate to that, he figured most everyone could feel what that was like. Moses certainly understood: that little terror on waking, for half a second, am I going to die today. Am I already dead?” (260)

Moses’s interpretation of the John Henry song emphasizes the universal human experience of facing mortality and daunting challenges. The record man, a figure who represents the commercialization of blues music and perhaps even a kind of cultural vampirism (as he is metaphorically “already dead”), adds another layer of complexity to this “singing.” His presence and his interest in recording Moses place the John Henry song within the context of the burgeoning recording industry and its impact on folk traditions. The mention of 78s by Skip James and Blind Lemon Jefferson grounds the narrative in a specific historical moment – around 1931 – and highlights the real blues artists whose music was being commodified and disseminated at that time.

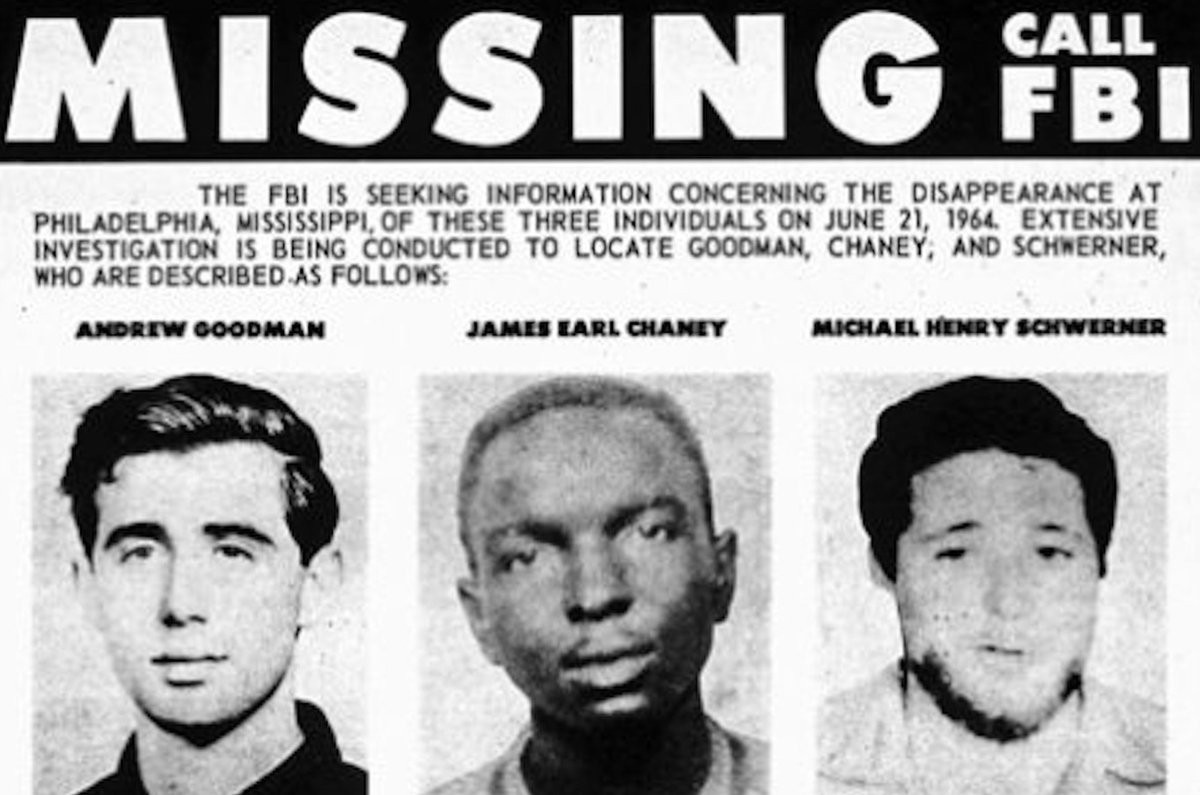

Whitehead subtly weaves in historical references throughout the novel, often with a layer of obscurity. The name “Andrew Goodman” is one such reference, echoing the tragic story of the Civil Rights worker murdered in Mississippi in 1964. Andrew Goodman, along with James Chaney and Michael Schwerner, became symbols of the struggle for voting rights and the violent racism of the Jim Crow South.

The search for the missing Civil Rights workers in Mississippi, a haunting echo in the narrative of “John Henry Days.”

The search for the missing Civil Rights workers in Mississippi, a haunting echo in the narrative of “John Henry Days.”

The bodies of the three Civil Rights workers uncovered, a stark reminder of the era’s brutal realities.

The bodies of the three Civil Rights workers uncovered, a stark reminder of the era’s brutal realities.

Alt text: FBI photo from 1964 showing the bodies of civil rights workers Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner being uncovered from an earthen dam in Mississippi, evidence in the Edgar Ray Killen trial.

The dialogue in the novel, “‘It’s not Mississippi in the fifties,’ one of J’s friends says about J’s nervousness about being in the south, in West Virgina. ‘It’s always Mississippi in the fifties,’ J. says,” underscores the enduring legacy of racism and injustice. Just as the historical Andrew Goodman, a young white man from New York, traveled to Mississippi to fight for Black voting rights, the Andrew Goodman in John Henry Days, a white record store owner in Black Chicago, operates in a space where racial lines are both blurred and sharply defined. Whitehead connects the historical struggle for voting rights directly to the narrative, reminding us that the John Henry song exists within a context of ongoing social and political battles. The overturning of the Voting Rights Act by the Supreme Court, mentioned in the original lecture, further emphasizes the contemporary relevance of these historical struggles and the ever-present threat of regression. “It’s not Mississippi in 1964,” we might have said before the Supreme Court decision, but “It’s always Mississippi in 1964” resonates even more powerfully in its aftermath. The Andrew Goodman of 1964 and the Andrew Goodman in John Henry Days become intertwined, representing a continuous thread of American history.

Another “singer” of the John Henry song in the novel is the statue maker. This artist, tasked with creating a physical representation of John Henry, is “forced to rely on what the story worked on his brain.” He attempts to reconstruct John Henry “from the footprint left in his psyche by the steeldriver’s great strides.” This process of artistic interpretation, of translating a song and a legend into a tangible form, is yet another layer of “re-singing.”

The John Henry statue in Talcott, West Virginia, a physical manifestation of the enduring legend.

The John Henry statue in Talcott, West Virginia, a physical manifestation of the enduring legend.

Alt text: A full shot of the John Henry statue in Talcott, WV, depicting a muscular Black man wielding a hammer, standing on a pedestal.

When J. and Pamela Street visit the statue in Talcott, we encounter yet another perspective on the John Henry song. Pamela, the daughter of a John Henry obsessed collector, embodies a complex and ambivalent relationship with the legend. For her, the John Henry song and her father’s obsession with it are intertwined with a difficult childhood. She recounts the story of a “creepy man” selling her father drill bits purportedly used in the Big Bend Tunnel, relics that to Pamela become “five scary, threatening fingers—’a railroad hand.'” This unsettling image reveals the darker, more ominous side of the legend, the potential for obsession and the toll it can take on personal lives.

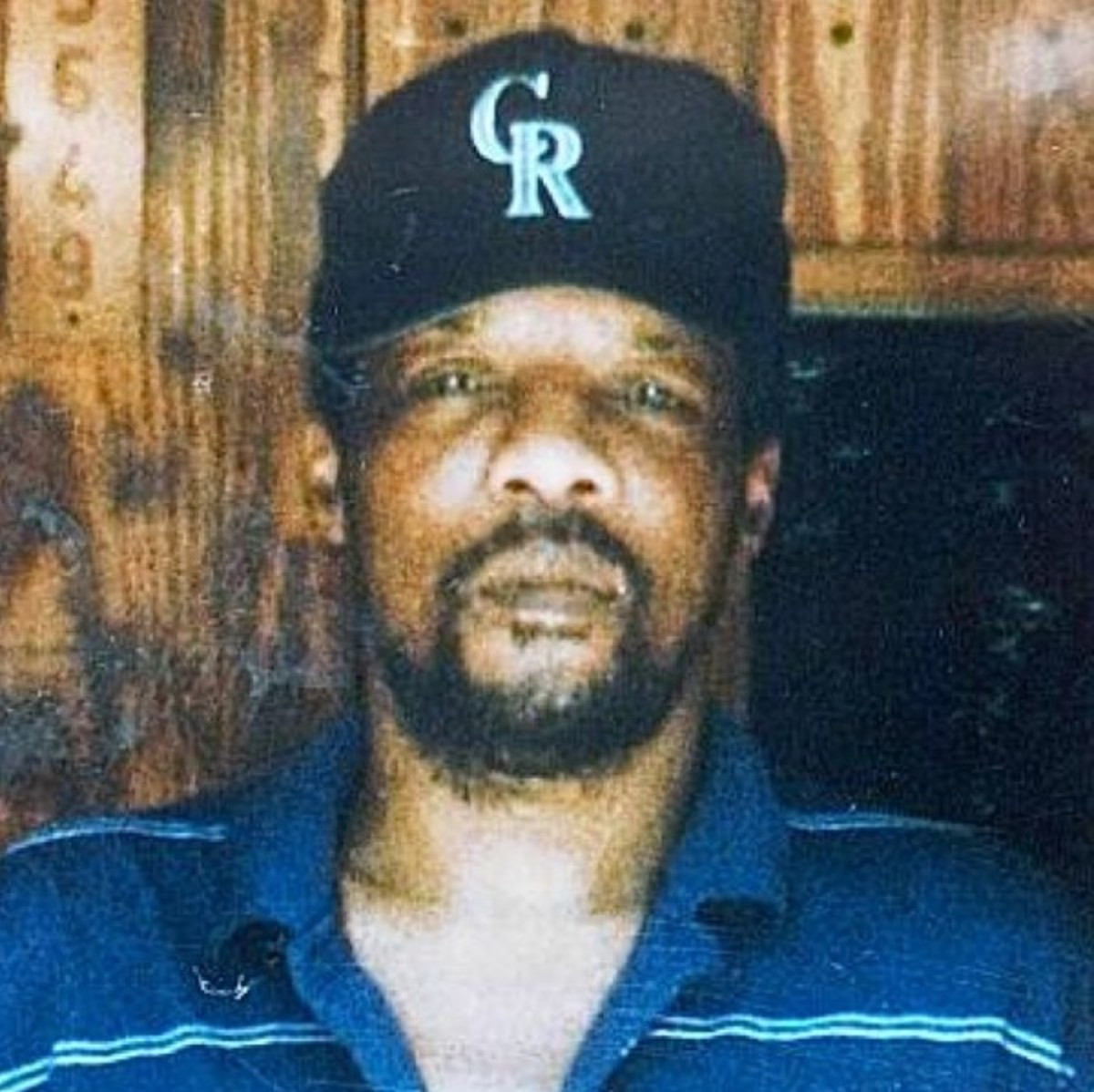

Pamela’s story about the statue being vandalized – “People come around and use it for target practice. One time they chained the statue to a pick-up and dragged it off the pedestal down the road there” – is, as the original lecture points out, deeply resonant. For a novel published in 2001, this act of dragging the statue becomes a chilling premonition of a real historical event: the murder of James Byrd, Jr. in Jasper, Texas in 1998. This act of vandalism, of physically desecrating the symbol of John Henry, foreshadows a far more brutal and racially motivated act of violence.

[PLAY “Two Towns of Jasper,” beginning at 00:45 and go to 03:07 of the provided link]

The sheriff in the film Two Towns of Jasper describes the horrific details of James Byrd, Jr.’s murder: three white men chaining Byrd to a pickup truck and dragging him to death.

James Byrd Jr., a victim of racial violence whose murder resonates with the themes of “John Henry Days.”

James Byrd Jr., a victim of racial violence whose murder resonates with the themes of “John Henry Days.”

Alt text: A portrait of James Byrd Jr., a Black man who was murdered in a racially motivated hate crime in Jasper, Texas.

This real-life atrocity, in the context of John Henry Days, becomes an “un-singing” of the John Henry song. It is an argument, as the lecture suggests, that “any lynching of a black person is an un-singing of the song—And that the song itself is a symbolic un-singing of any and every lynching of a black person, an affirmation of the power of a single African-American to deny and defeat the white power set against him, even if it costs him his life, but not his dignity.” The brutal reality of racial violence stands in stark opposition to the heroic narrative of John Henry, yet paradoxically, it also underscores the song’s enduring relevance as a symbol of Black resilience and dignity in the face of oppression.

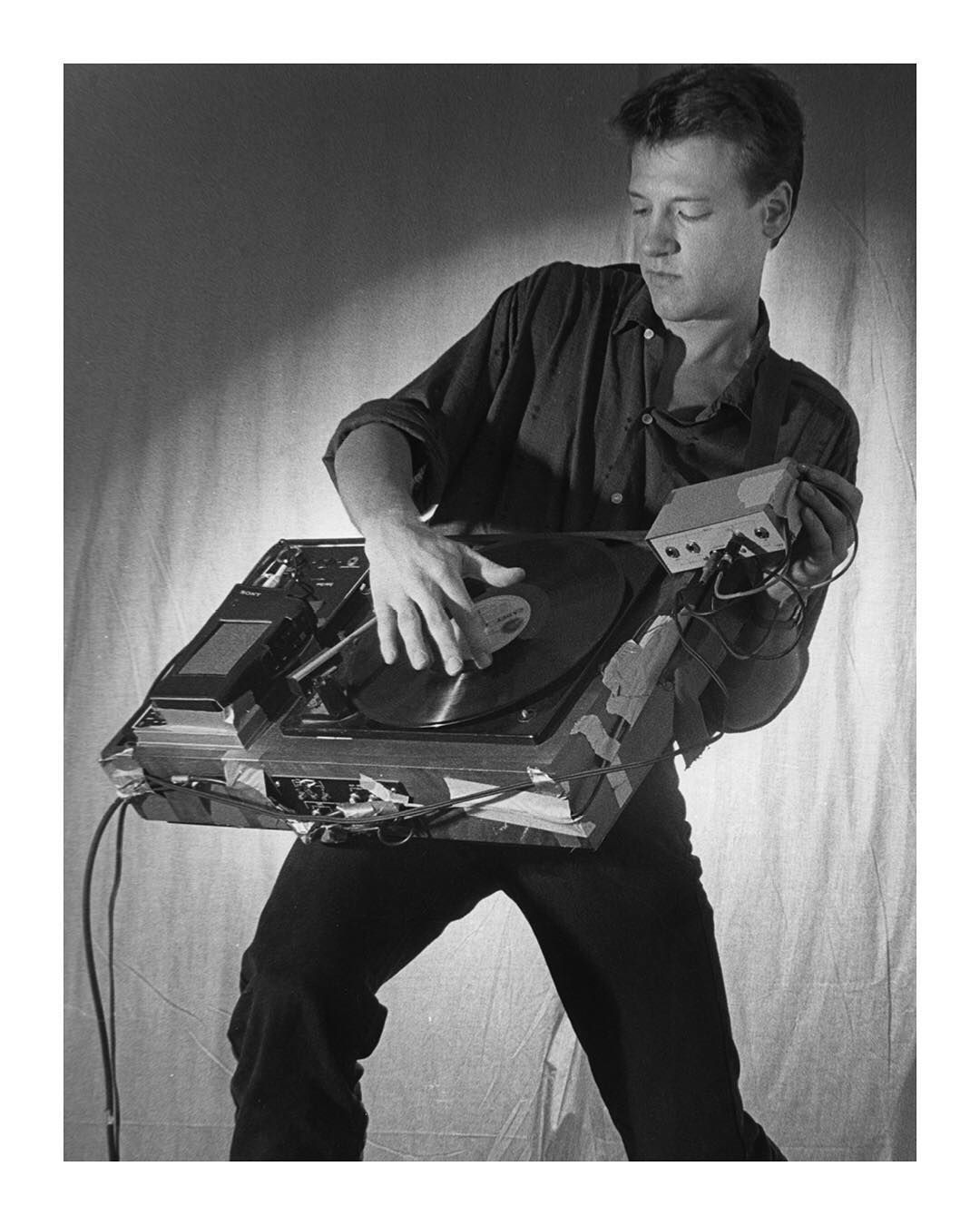

Christian Marclay’s “Guitar Drag” offers another powerful “version of this version of the song.” Marclay, known for his work The Clock, is an artist who recontextualizes existing media to create new meanings. His “Guitar Drag,” created in 2000, can be seen as a visceral and disturbing “re-singing” of the John Henry song through the lens of James Byrd Jr.’s murder.

Christian Marclay in his early performance days, exploring the intersection of sound and visual art.

Christian Marclay in his early performance days, exploring the intersection of sound and visual art.

Alt text: Christian Marclay performing with a phonoguitar, showcasing his early work with turntablism and sound manipulation.

A still from Christian Marclay’s “Guitar Drag,” a powerful and unsettling artwork.

A still from Christian Marclay’s “Guitar Drag,” a powerful and unsettling artwork.

Alt text: A still image from Christian Marclay’s “Guitar Drag” video, showing an electric guitar being dragged on a road, with sparks and debris flying.

Marclay’s description of “Guitar Drag” as “not supposed to be a comfortable experience” emphasizes its confrontational nature. It is a sonic and visual representation of violence and suffering, a deliberate “re-singing” of the murder of James Byrd, Jr., and, within the context of John Henry Days, a disturbing “re-singing” of an “un-singing” of “John Henry.”

Returning to the novel, Jennifer Sutter, J. Sutter’s aunt, represents yet another encounter with the John Henry song. In 1950s Harlem, Jennifer, a young girl taking piano lessons, discovers a piece of water-damaged sheet music in a forbidden music store. It is an old Jake Rose copyright, a relic from an earlier “singing” of the song. Despite her mother’s disapproval of the “filth,” Jennifer is captivated by the music. “She… propped up the sheet music on the music stand and played the song over and over, until it begins to talk to her.”

This scene echoes Constance Rourke’s theories in her 1931 book American Humor—A Study of the National Character. Rourke, considered a founder of American Studies, argued that American folklore and mythology stemmed from three archetypes: the Yankee, the Backwoodsman, and the Blackface Minstrel. She posited that even within the problematic minstrel tradition, “something real, some true speech, the straining voice of the back American speaking out of the mouth of the white American” could emerge. Similarly, in John Henry Days, the John Henry song, filtered through a Jewish songwriter (Jake Rose) and rediscovered by a Black girl in Harlem, transcends its origins and speaks directly to Jennifer: “There’s something sad about the song, but what she feels most is—pushed. The song pushes her… it quickens inside her.” The John Henry song possesses an inherent power, a force that resonates across generations and cultural contexts.

Alphonse Miggs, the stamp collector, offers a more twisted and unsettling “singing” of the John Henry song. Miggs, who saves J.’s life but also becomes a violent figure at the John Henry stamp unveiling, embodies the legend’s potential for distortion and misinterpretation. He becomes John Henry in a deeply disturbed way, forming the “Alphonse Miggs Liberation Front, of which he is the sole member.” Miggs’s violent outburst, triggered by the very celebration of John Henry, reveals the legend’s capacity to be co-opted and perverted.

In a starkly different context, a crackhead in a New York bodega accosts J., offering to “sing for my supper.” He then erupts into a raw, desperate rendition of the John Henry song: “‘This old hammer killed John Henry but it won’t kill me! This old hammer killed John Henry but it won’t kill me!'” In this encounter, the crackhead becomes a contemporary John Henry figure, battling against the overwhelming forces of poverty and addiction. J., in this scenario, represents the “steam drill,” the impersonal, powerful system that grinds individuals down. When J. gives the crackhead money, saying “You won,” it is a recognition of the human spirit’s resilience even in the face of defeat.

Mr. Street, Pamela’s father, dedicates his life to collecting John Henry memorabilia, creating his own personal John Henry Museum in his Harlem apartment. He embodies another form of “singing” the John Henry song: a solitary, obsessive devotion to preserving the legend. “In the morning he played the earliest versions of the song,” tracing its evolution through different recording technologies, “moving from cylinders to 78s to LPs to cassettes and eight-tracks and CDs, following the song as technology chases it.” Mr. Street’s museum, though largely unvisited, is his personal monument to John Henry, his way of keeping the song alive.

Finally, at the end of John Henry Days, we are given glimpses of John Henry himself. Throughout the novel, he has remained a spectral presence, appearing in fragments and allusions. We learn snippets of his life, such as being leased to the mines as a slave at the age of six. Even when we enter his consciousness, he remains largely silent, defined by his actions and his internal struggles. His nightmare, in which “rivers of blood” replace light and the mountain turns to “flesh,” is a powerful and disturbing image of the physical and psychological toll of his labor.

“He had traveled through a series of fever dreams all night. They were coupled together like train cars. He knew that the caboose contained morning and each time he fell asleep he hoped that this time he would step into it. But he opened the door to the next car and stepped again into nightmare . . . He had lost two days’ wages laid up in bed.” (239)

This passage, as the original lecture notes, is itself “a song.” It captures the rhythm and emotional weight of the John Henry song, translating it into prose. It speaks to the universal experience of relentless labor, the cyclical nature of hardship, and the yearning for respite.

In the concluding scenes, Pamela and J. search for a place to scatter Mr. Street’s ashes on the mountain. They stumble upon remnants of a cemetery, a possible resting place for John Henry himself. Pamela, in this moment of connection to her father and the legend, “sings the song under her breath, as the song’s Polly Ann singing to her father’s John Henry.” This intimate, personal “singing” underscores the song’s ability to connect individuals across generations and through personal grief.

As Pamela and J. walk to the mountain, Pamela reflects, “She says there are many versions of the song, as many versions as there are people who sing it.” This statement encapsulates the central theme of John Henry Days: the John Henry song is not a fixed text but a constantly evolving and reinterpreted narrative.

Ultimately, Mr. Street, in his solitary museum, becomes a John Henry figure himself. He prepares daily for crowds that never arrive, delivering his “guided tour, his speech about John Henry, to his countless invisible audiences.” In a poignant reversal, Mr. Street, the devoted keeper of the legend, is ultimately defeated by the very force John Henry defied: the steam drill. For Mr. Street, “John Henry has turned into the mountain he can’t beat. John Henry has turned into the steam drill.” The indifference and neglect he faces become his insurmountable obstacle, his personal steam drill.

The John Henry song, as explored through the multifaceted lens of John Henry Days, is far more than a simple ballad. It is a dynamic and evolving cultural artifact, constantly being re-sung and reinterpreted across time and contexts. Whitehead’s novel masterfully captures this enduring resonance, revealing how the John Henry song reflects and refracts the complexities of American identity, history, race, and the ongoing struggle between human spirit and relentless progress. It is a testament to the power of folk song to adapt, endure, and continue to speak to us across generations.

(Seminar Discussion – Optional)

To further appreciate the enduring power and diverse interpretations of the John Henry song, consider listening to Drive-By Truckers’ “The Day John Henry Died.” This modern rendition offers a contemporary perspective on the legend, highlighting themes of labor, obsolescence, and the changing landscape of work in America. It serves as a powerful reminder that the John Henry song continues to resonate and evolve, reflecting our ongoing dialogue with history and the enduring human spirit in the face of change.