Learning a new language, especially one as intricate as Japanese, can feel like an uphill battle if you’re solely relying on textbooks and rote memorization. Vocabulary lists and grammar rules are essential, but they often lack the spark to truly ignite your passion and keep you motivated in the long run. If your goal is to learn Japanese, tapping into your interests is key. Perhaps it’s the captivating world of anime, the storytelling in manga and novels, or the desire to connect with Japanese speakers in real conversations. Whatever your motivation, finding that “something you give a damn about” is crucial for sustained language learning. Many of us have experienced the frustration of language classes in school, where the lack of personal connection to the language often leads to losing momentum and eventually giving up before reaching fluency. Sometimes, language choices are driven by convenience rather than genuine interest, like fitting a class into a busy schedule. It’s a common experience, but not the most effective path to language mastery.

Even when we start with strong initial motivation, another hurdle often arises: delaying immersion in authentic language content. We often believe we need to grind through countless textbook chapters before we’re “ready” to engage with “real” Japanese. However, the problem is that textbook material can be incredibly dry, making it difficult to maintain enthusiasm and persistence. Even if that magical “ready” moment existed, the journey to get there through dull material might be too arduous for many.

The sooner you immerse yourself in the Japanese content you genuinely love, the more rewarding your learning journey will become. Yes, grappling with authentic Japanese can feel challenging, like hitting a wall. But let’s be honest, textbooks can feel just as frustrating, and the reward for pushing through textbook exercises rarely matches the thrill of real-world comprehension. No textbook could ever replicate the excitement I felt when I finally understood a pun in the Japanese manga I was reading.

This realization led me to explore Japanese pop music. I discovered a growing interest in J-pop, but felt frustrated by my inability to understand the lyrics. This frustration sparked an idea: why not use this passion as a learning opportunity? Especially since I enjoy singing and wanted to sing along to my favorite Japanese Songs.

My current Japanese level, after years of on-and-off study through classes and self-learning, is somewhere between beginner and intermediate, with noticeable gaps in my knowledge. While translating entire songs myself is still beyond my reach, the internet offers a wealth of resources to bridge that gap. Using these resources has proven to be an incredibly effective and motivating way to learn Japanese. If you’re intrigued to try this method, I’ve compiled some helpful tips and warnings based on my experience, which I believe will be valuable regardless of your current Japanese proficiency.

Picking the Right Japanese Song for Learning

When selecting a japanese song for language study, three key factors come into play. Firstly, and most importantly, you must genuinely love the song. This method involves repeated listening and in-depth study, which can become tedious if you don’t connect with the music. The goal is to still enjoy the song even after countless repetitions as you dissect and learn from it.

Secondly, readily available online translations and romaji transliterations are essential. While fan translations may vary in quality, having multiple versions can be beneficial, offering diverse interpretations and learning opportunities, as we’ll discuss later.

It’s important to acknowledge that many fan translation sites operate in a legal gray area, so I won’t directly link to specific sites here. However, a simple Google search will lead you to numerous resources. You might also find fan-subbed videos, some of which are excellent, while others can be less reliable.

Ideally, focus on artists with international aspirations who provide official English subtitles on their music videos. For example, I’ll be using “RPG” by Sekai no Owari as a case study, a band known for providing English subtitles on their official videos. By clicking the “CC” button in the video’s lower right corner, you can access these subtitles. Unfortunately, directly copying these subtitles isn’t always straightforward, often requiring manual typing as you listen. If you opt for lyrics sites, copy-pasting is generally possible, simplifying the process.

Thirdly, before diving deep, perform a preliminary sing-along using only the romaji transliteration. This initial step helps avoid investing significant effort into a song only to discover it’s pitched too high or low for your vocal range. It also helps gauge the song’s tempo and rhythmic complexity, preventing you from choosing a song that’s too fast or rhythmically challenging for comfortable learning. (For instance, this song turned out to be too ambitious for a beginner).

Simple folk songs or older japanese songs can be a gentler starting point, often avoiding these issues. This folk song is a personal favorite, and you might find this modern rendition, created to support victims of the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami, even more appealing (though be warned, it’s emotionally moving). Ultimately, you’ll likely find the most success and enjoyment studying japanese songs you already know and love.

Structuring Your Japanese Song Study

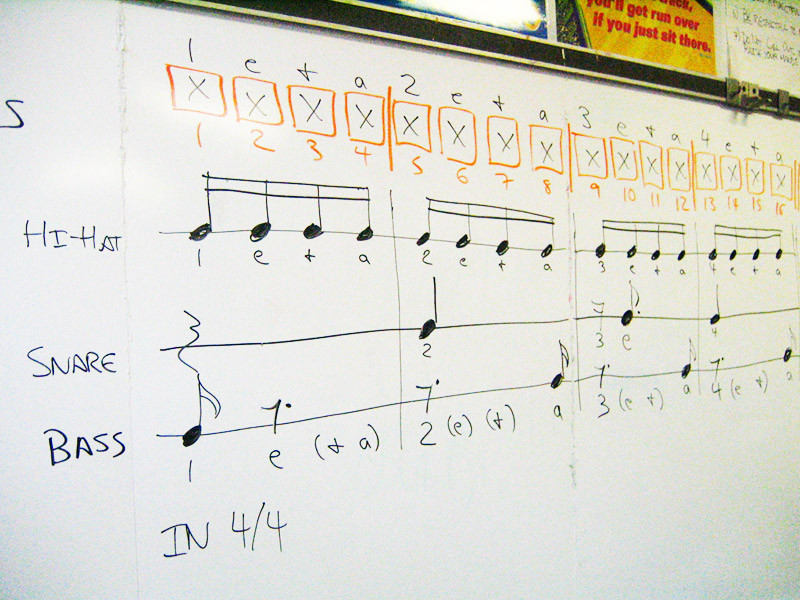

music theory on a white board drums

music theory on a white board drums

Source: Warren B

Following my method involves copying and pasting online resources into a file. It’s crucial to save anything interesting you find, as unofficial translations can disappear unexpectedly due to copyright concerns.

My first step is to save the complete translation. Then, separately, I begin structuring the romaji lyrics alongside the original Japanese lyrics. Here’s the first line of the Sekai no Owari song, “RPG”:

空(そら)は 青(あお)く 澄(す)み 渡(わた)り 海(うみ)を 目指(めざ)して 歩(ある)く

Sora wa aoku sumi watari umi wo mezashite aruku

Now, before proceeding, it’s worth addressing the romaji debate. Many language learners strongly advise against using romaji when studying Japanese. Ideally, if I could easily obtain lyrics with furigana (hiragana readings above kanji) in a copy-pasteable format, I would prefer that. However, this has proven difficult to find. For my purposes, this isn’t primarily a reading exercise, so I’m comfortable using romaji. My kana reading is already fluent, and romaji doesn’t hinder it. It’s also important to remember that native speakers naturally learn words verbally before learning to write them – children speak their language before learning to read and write.

So, while offers to furigana-ize my lyrics are welcome, let’s set aside the romaji debate for now and continue.

Next, I align the kanji roughly with the romaji words in a table format:

空(そら)は 青(あお)く 澄(す)み 渡(わた)り 海(うみ)を 目指(めざ)して 歩(ある)く Sora wa aoku sumiwatari umi wo mezashite aruku

Then, I look up unfamiliar vocabulary and grammar points, ensuring I understand the rationale behind the translations. I avoid attempting to directly line up entire lines of English translation with the Japanese text, as word order differs significantly between the languages. My goal is to think in Japanese as much as possible. Therefore, I insert the definitions of only the words I don’t know directly above the kanji in my table.

For “RPG,” I found three translations online, which we’ll compare later. For now, let’s use the translation: “Under the clear blue sky, we are walking to the sea.” Looking up the new words gives me:

be perfectly clear aim at 空(そら)は 青(あお)く 澄(す)み 渡(わた)り 海(うみ)を 目指(めざ)して 歩(ある)く Sora wa aoku sumiwatari umi wo mezashite aruku

“Sumi watari” seems like a more poetic way of expressing “clear blue sky.” I make a mental note and move on. As the wise Koichi-sensei of Tofugu has said, “Most people spend way too much time obsessing over the things they can’t figure out.” I grasp the general meaning of the line, so I’m ready to proceed.

After completing this process for the entire song, I annotate lines as needed to aid with singing. One annotation I’ve already made in the example above is removing the “w” from the particle を (wo) in the romaji. In singing, the “w” in を is sometimes pronounced, but this singer doesn’t, and I prefer to mimic their pronunciation.

Singing often involves unique pronunciations that differ from spoken Japanese, and some affect how words align with the musical notes. I use specific annotations to address these. For example, syllable-final ん (n) is sometimes sung as a separate syllable to fit the rhythm. In “RPG,” the word “自分” (jibun – myself) is sung across three notes. So I bold the “n” in the romaji: Jibun.

Long vowels and vowel sequences, like “ou” in もう (mou – already) or “ai” in ない (nai – not), might be sung as distinct separate vowels. I use a period to mark syllable breaks in such cases. For example, “sekai” (world) might be annotated as seka.i if sung across three notes.

I also use annotations to highlight unexpected rhythms. I bold a vowel or syllable when the downbeat syllable is rhythmically surprising:

大切(たいせつ)な 何(なに)か が 壊(こわ)れた あの 夜(よる)に Taisetsuna nani ka ga kowareta ano yoru ni

And I italicize syllables that are unstressed or barely pronounced, important for rhythm awareness:

「目的」 という 大事なもの を 思い出して “Moku tek_i_” to iu daijina mono o omoidashite

For particularly challenging rhythms, if you read music, you can even add musical notation. However, if you feel the need to do this immediately, the song might be too difficult to start with.

Once you’ve annotated the entire song and still enjoy it, play the music video and sing along!

Basic Japanese Language Skills Learned Through Songs

vintage tub of tinkertoys

vintage tub of tinkertoys

Source: Mike Mozart

I recently read a fascinating book about polyglots. One recurring theme was the importance of consistent, daily interaction with the language, described by one polyglot as “Spend time tinkering with the language every day.” This perfectly describes my song-based learning approach. If someone who has mastered seventeen languages recommends it, it’s worth taking seriously.

While this method isn’t a structured curriculum, it yields tangible learning benefits. Vocabulary acquisition is a significant one. Learning a song line embeds those words in your memory, and artists, especially within their discography, often reuse vocabulary. While song lyrics might not always prioritize the most practical everyday vocabulary – how often do you discuss celestial bodies or sleepless nights outside of Sekai no Owari songs? – the same can be said for many textbook introductory words. Words learned in a meaningful, personally relevant context are far more memorable.

This principle extends to grammar. Which of these is more memorable? This line from another Sekai no Owari song:

幻(まぼろし)に 夢(ゆめ)で 逢(あ)えたら それは 幻(まぼろし)じゃない

Maboroshi ni yume de aetara sore wa maboroshi janai

If you meet a phantom in a dream, then it’s not a phantom

Or this line from a nameless grammar website:

暇(ひま)だったら、 遊(あそ)びに 行(い)くよ。

Hima dattara, asobi ni iku yo.

If I am free, I will go play.

Despite not explicitly focusing on reading skills through song study, vocabulary gains indirectly benefit reading comprehension. As mentioned earlier, native speakers learn to speak before reading. When encountering kanji for words learned through songs in my formal studies, recognition is significantly faster and easier. When 星(ほし) (hoshi – star) appeared on WaniKani, instead of feeling overwhelmed, I felt a surge of recognition because I already knew “hoshi” meant “star” from songs. It was like greeting an old friend in a new setting, rather than meeting a stranger.

Regarding reading practice specifically, while I can already sing parts of “RPG” from memory, my next step is to remove the romaji and rely solely on Japanese lyrics. I experimented with karaoke versions that provide furigana, and I could mostly keep up, but the jarringly bad musical arrangements were a deal-breaker. I prefer singing along with the original artists, not generic elevator music versions.

Another crucial benefit is pronunciation fluency. Studying independently offers limited speaking opportunities. Singing forces you to keep pace with the music, training you to articulate syllables smoothly and naturally, improving overall pronunciation and rhythm.

Deeper Linguistic Insights from Japanese Songs

mother and son on a beach in deep water

mother and son on a beach in deep water

Source: Aaron Moraes

An intriguing aspect of learning with japanese songs is delving into the multiple interpretations of even simple lines. Songs highlight translation nuances because Japanese grammar differs significantly from English, and song lyrics often lean towards poetic expression, not simple textbook phrases like “My name is Linda, pleased to meet you.”

For “RPG,” besides the official translation, I found two fan translations: [Translation 1](example.com – hypothetical link) and [Translation 2](another-example.com – hypothetical link), the latter from a consistently reliable site. Even a simple line like the first line of “RPG” varies across translations:

空(そら)は 青(あお)く 澄(す)み 渡(わた)り 海(うみ)を 目指(めざ)して 歩(ある)く

Sora wa aoku sumi watari umi wo mezashite aruku

Official: Under the clear blue sky, we are walking to the sea

Fan Translation 1: The sky was a clear blue as we each walked toward the beach

Fan Translation 2: And the sky is full of a beautiful blue, to the sea we walk confidently

If a simple phrase about walking to the beach under a blue sky can be interpreted in three ways, imagine the variations in more metaphorical lines:

「 方法(Houhou)」という 悪魔(あくま)にとり 憑(つ)かれないで

“Houhou” to iu akuma ni tori tsukare naide

Official: Don’t be possessed by the demon called “The method”

Fan Translation 1: Don’t get possessed by the evils of wondering “how”

Fan Translation 2: Don’t get carried away trying to find “the way”

The poetic nature of lyrics means that non-native translators might sometimes miss nuances. In one instance, fan translations seemed to misinterpret the intended meaning. Consider these translations of:

” 煌(き)めき”のような 人生(じんせい)の 中(なか)で

“Kirameki” no youna jinsei no naka de

Fan Translation 1: In the midst of my “bright and shining” life,

Fan Translation 2: In my “glittering” life

Official: In a life that’s like a flash that ends so fast

The official translation reveals a different, darker tone, consistent with Sekai no Owari’s style of upbeat melodies often paired with melancholic lyrics about mortality. (Their debut hit was, surprisingly, a song about a deceased infant).

Ultimately, songwriting is art, and non-native translators might miss cultural references or metaphorical layers. Conversely, official translations can be deliberately non-literal. As discussed elsewhere on Tofugu, media localization involves more than just direct translation, considering marketing and cultural adaptation. This is evident in movie and book titles adapted for different markets. In another Sekai no Owari song, the title honou 炎(ほのう)とmori 森(もり)のカーニバル, literally “carnival of flame and forest” (even using the English word “carnival” in katakana), is officially translated as “Tokyo Fantasy” in the video subtitles here. This likely ties into a movie of the same name, aiming for cross-promotion. While fan translations might lack linguistic polish, official translations might prioritize broader marketing goals over linguistic accuracy for language learners.

Cautions When Learning Japanese from Songs

visual description of the image

visual description of the image

Source: Elliott Brown

Learning Japanese through songs has potential drawbacks to be mindful of. The most immediate is earworms – having the same song stuck in your head on repeat. While you need to genuinely enjoy the song for this method, overexposure can lead to fatigue or even disliking the song, which is unfortunate.

More importantly, similar to the need for caution when learning from anime to avoid adopting unnatural speech patterns, be aware of song lyrics that are inappropriate for everyday conversation. Songs, across all languages, differ from spoken language in grammar, pronunciation, and word choice.

Regarding vocabulary, as mentioned, song lyrics might overemphasize certain themes like stars and love compared to everyday conversations. The use of “I love you” in songs across cultures far exceeds its frequency in real-life spoken interactions. Searching for ありがちな 歌詞(かし) (arigachi na kashi – common lyrics) online reveals numerous blogs listing J-pop clichés.

One specific vocabulary caution is the pronoun boku (僕). Textbooks correctly state that women generally don’t use boku. This holds truer in real life than song lyrics suggest. Female singers commonly adopt a “male perspective” in songs, using pronouns and vocabulary they wouldn’t use in everyday speech. The same applies to male singers. Crucially: just because it’s sung doesn’t mean it’s commonly said.

Pronoun usage highlights a broader grammatical point: songs tend to overuse personal pronouns, especially first and second person pronouns. This is a significant point of divergence between Japanese and English grammar and a common challenge for English speakers. Japanese often omits the subject if it’s clear from context. The natural way to say “I went” is 行きました (ikimashita). Using 私はいきました (watashi wa ikimashita) adds emphasis, closer to “Me? I went.” This nuance is easily missed due to the frequent use of watashi, boku, and kimi (you) in song lyrics.

Pronunciation in singing also deviates from standard spoken Japanese. Syllable-final ん (n) might be pronounced as a separate syllable, as mentioned earlier. The particle を (o/wo) is sometimes pronounced “wo,” represented in some romaji systems. You can hear this in this song in the first verse’s last line: Karappo no kaban wo kyutto kakaete.

Another interesting phenomenon is the imitation of American English pronunciation in Japanese songs. Similar to British rock singers adopting American accents, there’s a perception that American English is the “authentic” language of rock music. While less pervasive in Japanese, subtle American English pronunciation influences exist. One example is the American “R” sound. Sekai no Owari’s lead singer notably doesn’t use this, his “R” is distinctly Japanese, highlighting how unusual the Americanized “R” can sound in J-pop when absent.

Linguists have identified other potential American English pronunciation influences in J-pop singing:

- The consonant /sh/ (as in し): Japanese /sh/ is heavily palatalized, while American English /sh/ is post-alveolar. Some singers imitate the American sound.

- Vowel sequences (/ai/, /ae/ etc.) may be pronounced almost like diphthongs, more gliding sounds than distinct vowels.

- The /u/ sound, especially in /ou/, is sometimes pronounced with stronger lip rounding and emphasis.

- Heavier aspiration on /t/ sounds.

Finally, be wary of becoming too comfortable singing along without understanding the lyrics’ meaning. Years of choral singing in languages I didn’t understand made me susceptible to this. If I find myself singing mindlessly in the car, I make sure to revisit the translations. The goal is comprehension, even if song lyrics aren’t the most practical everyday Japanese. Ultimately, the aim is to have meaningful conversations about love and stars in the sky, and genuinely understand each other. And that will be a beautiful outcome of learning japanese songs.