In 1894, James Mooney, a dedicated scholar of American Indian culture and language, embarked on a significant project: recording the songs of the Ghost Dance in various Native American languages. These invaluable recordings, known as the James Mooney Recordings of American Indian Ghost Dance Songs, have been recently revitalized and are now featured in the presentation, Emile Berliner and the Birth of the Recording Industry. Interestingly, it is believed that Mooney himself may have sung these recordings, a common practice at the time for ethnographers. Lacking widespread recording technology, they relied on memorization to preserve and accurately represent the songs and stories of the cultures they studied. This meticulous approach ensured the preservation of cultural heritage through human memory, a testament to the dedication of early ethnographers. Even today, learning and reproducing songs and stories remains a vital part of ethnographic fieldwork, offering deep insights through participant observation and the act of memorization and repetition.

This particular recording showcases a Caddo Ghost Dance song. The Caddo Nation, a confederation of Southeastern Indian peoples, resided on a reservation in Oklahoma during this period.

{mediaObjectId:'517518FC117F012AE0538C93F116012A',metadata:["James Moody. 'Caddo Ghost Dance Song no. 2'"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

The Ghost Dance emerged as a profound spiritual movement among Western American Indians, originating around 1869 with the Paiute elder Wodziwob. His visions spoke of a revitalized Earth and ancestral aid for the Paiute people, a message of hope following devastating European disease outbreaks, possibly including a typhoid epidemic in 1867. Wodziwob’s initial prophecies described a cataclysm that would remove Europeans, leaving only Indians, but evolved to envision a universal event removing all people, followed by the miraculous return of those who upheld ancestral spiritual practices. His later visions shifted again, predicting a peaceful, immortal life for followers, without the destruction of Europeans. Central to this spiritual practice was a communal circle dance ceremony, guided by Wodziwob’s visions. He passed away in 1872, but his spiritual seeds had been sown.

A Northern Paiute named Wovoka, also known as Jack Wilson, experienced a pivotal dream during the solar eclipse on January 1, 1889, echoing Wodziwob’s prophecies. Wovoka envisioned the departure or disappearance of European settlers, the return of buffalo herds, and the restoration of land to Indian peoples across the continent. Ancestors would return to life, ushering in an era of peace. Raised by the European American family of David Wilson after his father’s death, Wovoka’s teachings emphasized peaceful coexistence with white Americans. Having some exposure to Christianity, his teachings incorporated elements of Christian thought, including references to Jesus or a messianic figure. Wovoka taught that the circle dance ceremony would actualize his vision of a peaceful world.

News of Wovoka, the new prophet, spread rapidly, drawing representatives from diverse tribes to seek his wisdom. Letters disseminated the vision and ceremony details to other Indian nations, while movement leaders traveled to various communities to educate them about the prophecy and the dance.

A group of dancers in Native American dress form a circle around an American Flag.

A group of dancers in Native American dress form a circle around an American Flag.

Dancing holds a significant place in many Indian spiritual traditions. The Ghost Dance drew upon the round dance, a common practice among numerous Indian peoples, serving both social and healing purposes. Participants joined hands, moving in a circle with a shuffling side-to-side step, swaying to the rhythm of their songs. Traditional round dances often feature a central drum, but the Ghost Dance ceremony typically omitted drums, sometimes featuring a central pole or tree, or simply an open space. Specifics of the dance varied among different groups.

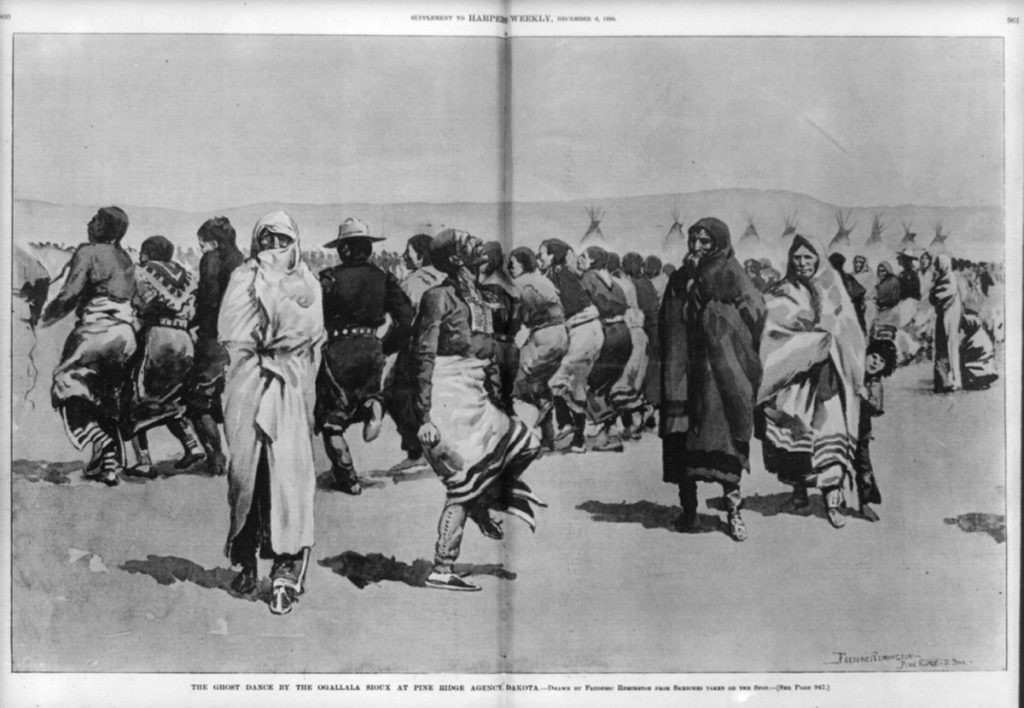

Mooney noted that the dance could induce a trance state in participants, with some actively seeking this altered consciousness. To facilitate trance, objects like feathers or cloths were waved within the circle as focal points. Faster-paced songs aided dancers aiming for trance and visions. Those experiencing trance might leave the dance circle to dance individually or lie on the ground. As depicted in Frederic Remington’s print, the dancers form a background circle, while foreground figures represent individuals who have entered trance states, aligning with Mooney’s descriptions.

Ghost Dance songs followed a distinct pattern: a line repeated twice, followed by another line repeated twice, and so on. Judith Gray, an expert on American Indian music and song at the American Folklife Center, identifies this pattern as common among the Paiute and other Northwest Plateau peoples, but not among Plains Indians or many other groups adopting the Ghost Dance. Nonetheless, this song structure was embraced and adapted as various groups created Ghost Dance songs in their own languages, showcasing cultural exchange and adaptation in musical expression.

This recording presents two Arapaho Ghost Dance Songs, the first being slower in tempo than the second.

{mediaObjectId:'517518D47350014AE0538C93F116014A',metadata:["James Moody. 'Arapaho Ghost Dance Songs no. 44 and 45'"],mediaType:'A',playerSize:'mediumStandard'}

The Ghost Dance ceremony rapidly spread across numerous Indian communities, primarily in Western states. This intertribal interaction and the dance’s rapid dissemination alarmed European Americans, becoming a concern for the U.S. Army.

While many European Americans perceived the Ghost Dance as a militant and aggressive movement, it was fundamentally a peaceful resistance rooted in Indian beliefs. It was also an expression of desperation amidst treaty violations and forced relocation to reservations. For Plains Indians, the era was marked by starvation due to the buffalo slaughter, which decimated their way of life and primary food source. From the Indian perspective, Europeans were not only destroying their culture but also devastating the plains’ natural resources, rendering them uninhabitable. European American anxieties often dismissed the Ghost Dance as irrational, but from the Indian viewpoint, the actions taken against them and their way of life were profoundly irrational.

James Mooney authored a book on the Ghost Dance, aiming to counteract prejudiced and inaccurate newspaper portrayals. His research initially appeared in an 1890 report, later expanded into a book in 1896. The press fueled public fear, portraying the dance as dangerous and potentially leading to an Indian uprising. Mooney emphatically clarified its peaceful nature. His introduction details fieldwork from 1890-1894, involving extensive travel and engagement with approximately twenty tribes. As a participant observer, he danced and sang with the Arapaho and Cheyenne, consulted with adherents, and took photographs. The emergence of a new religion rapidly spreading across cultural and linguistic boundaries fascinated ethnographers, making the Ghost Dance a subject of intense scholarly interest as a remarkably rare phenomenon.

Mooney traced the Ghost Dance movement’s beliefs to earlier spiritual prophecies within various Indian groups, foretelling land restoration and a return to pre-European life. These prophecies arose soon after initial settlements and conflicts began. Therefore, while the Ghost Dance seemed sudden, its underlying ideas had deep roots within diverse Indian cultures, reflecting long-held hopes for renewal and justice.

An elderly man lies in the snow.

An elderly man lies in the snow.

The Ghost Dance became tragically linked to the Wounded Knee Massacre. On December 15, 1890, during a dispute over a Ghost Dance ceremony, police killed Chief Sitting Bull at Standing Rock Reservation. Subsequently, over 300 Miniconjou Lakota, led by Chief Spotted Elk (Big Foot), sought refuge at Pine Ridge Reservation. They were intercepted by the U.S. Army at Wounded Knee Creek and held under armed guard, including Hotchkiss guns. Men were separated from women and children, and as soldiers disarmed the men, gunfire erupted. Accounts vary, but one suggests a deaf man refused to relinquish his rifle. The death toll remains disputed, but estimates range from 150 to 300 Indians killed, many unarmed women and children. Higher figures include those who died from exposure and wounds post-massacre. Spotted Elk, unarmed and ill with pneumonia, was killed on the ground. The Army lost 25 soldiers.

Mooney provides a detailed account of the events leading to, during, and after Wounded Knee, incorporating firsthand testimonies and accounts from Indians who arrived soon after to aid survivors. He attributes differing death toll figures to the exclusion of those who died later from wounds or exposure, estimating around 300 total deaths.

Amidst Ghost Dance anxieties, the event was termed a “battle,” soldiers were hailed as heroes and awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Today, it is recognized as the Wounded Knee Massacre. This shift in perspective gained momentum with Dee Brown’s 1971 book, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West, and the rise of the Indian civil rights movement, finally amplifying the Indian perspective on history. This period marked a turning point in understanding American Indian history.

Two years after Wounded Knee, Mooney published his research, intending to quell fears and prevent further violence. He became a leading expert on the Ghost Dance through newspaper interviews. His recordings of Ghost Dance songs aimed to preserve the reality of the Ghost Dance. However, popular perception at the time viewed the Ghost Dance as a threat, ending with the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890. Some historical narratives still perpetuate this view. The Bureau of Indian Affairs attempted to ban the Ghost Dance, reinforcing the idea of its termination. Yet, the Ghost Dance ceremony persisted into the early 20th century, and some songs endure in Indian traditions today. The American Folklife Center collections contain examples of Ghost Dance songs in various languages (available on site), sometimes cataloged as “new religion songs.”

In 1973, a Lakota Sioux protest at Wounded Knee, part of the Indian rights movement, underscored the enduring significance of these events for Native Americans. Elements of Ghost Dance spirituality, such as peaceful resistance to prejudice and oppression, resonate in contemporary Indian rights expressions. Listen to the recordings and consider its profound legacy.

Notes