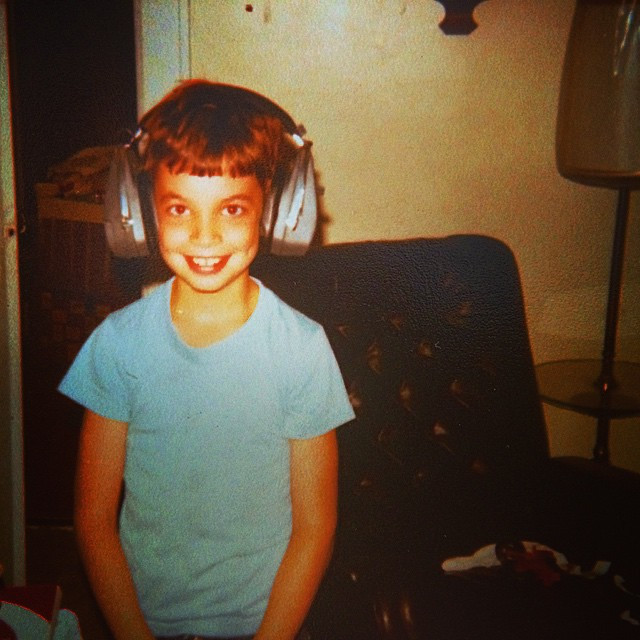

In 1979, for a nine-year-old tuning into the radio waves, Charlie Daniels’ “The Devil Went Down To Georgia” was inescapable. It wasn’t confined to country stations; this “Georgia Devil Song” dominated rock, top-40, even college radio. This proto-culture war anthem, nodding to the classic Faustian bargain, became a ubiquitous soundscape of the late 70s. Even if your mom, like mine, wasn’t a fan, going so far as to “ban” the “devil song” from our household, its infectious energy and narrative pull were undeniable. My youthful rebellion questioned her concerns – was she genuinely worried about soul-selling pacts? Surely, if the devil was in the soul-trading business, he’d be more sophisticated, and probably a better musician than us kids.

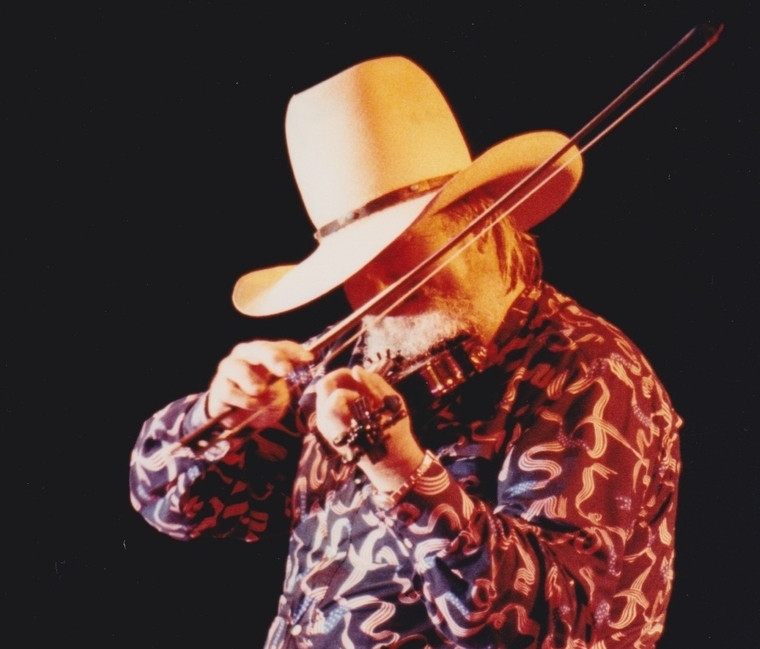

Charlie Daniels at Cornerstone Festival '94 (Photo by Bill Latocki)

Charlie Daniels at Cornerstone Festival '94 (Photo by Bill Latocki)

My mom’s real issue wasn’t metaphysical deals with the devil; it was the “sonofabitch” line. She knew, and we knew, that despite the radio edits, those were the words echoing in our young minds and hearts every time the “georgia devil song” blasted from the speakers. And, of course, she was right to be aware of the song’s impact.

The music world mourned a significant loss with Charlie Daniels’ passing on July 6, 2020. His influence spanned decades and genres. From writing an Elvis tune in 1964 to playing on Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline and collaborating with Leonard Cohen, George Harrison, and Emmylou Harris, Daniels’ musical footprint was vast and varied. His band’s festival in the early 70s was a melting pot of genres, featuring Lynyrd Skynyrd, James Brown, John Prine, and Stevie Ray Vaughn. Yet, like many artists, one song often eclipses a diverse career, and for Daniels, it’s undoubtedly “The Devil Went Down To Georgia.” This “georgia devil song” earned him a Grammy and cemented his place in the cultural lexicon, further boosted by its inclusion in the Urban Cowboy soundtrack in 1980. His public persona also evolved, transitioning from a counter-culture figure who once supported Jimmy Carter to a staunch Republican and NRA advocate.

In 1994, I had the opportunity to interview Charlie Daniels backstage at the Cornerstone Festival before his mainstage performance. By then, he had embraced Christianity and sobriety, a stark contrast to his 70s rebel image. He was touring with The Door, a gospel country album, aiming to connect with a Christian audience. His Cornerstone set was a masterclass in Southern-fried country-rock, showcasing a level of musical polish rarely seen in Christian music circles. The crowd enthusiastically received his classics like “The Legend of Wooly Swamp” and even a Rolling Stones cover of “Satisfaction.” However, the atmosphere shifted when Daniels segued into political commentary, advocating harsh, simplistic solutions to violent crime, blaming it on drugs, and mocking then Surgeon General Jocelyn Elders’ more nuanced approach to drug policy. Elders, the first African American woman Surgeon General, faced backlash and resignation for suggesting decriminalization and medicinal marijuana studies – ideas now widely discussed and even implemented.

While some locals in the Cornerstone audience applauded Daniels’ pronouncements, many regular festival-goers headed for the exits. His simplistic, politically charged views clashed sharply with Cornerstone’s ethos of grace and thoughtful engagement with complex social issues. (The presence of a scantily clad female backing vocalist also raised eyebrows within the more conservative segments of the audience.) In retrospect, this performance became a microcosm of the burgeoning Red State/Blue State divide in America and the evangelical community’s growing attraction to simplistic political power over nuanced, compassionate solutions. For me, at 24, it was a pivotal moment. I had been drawn to Daniels’ rebellious spirit and his “kick the devil’s ass” attitude, epitomized in the “georgia devil song”. But that night, I began to understand that the devil’s bargains are far more subtle than grand Faustian deals. The golden fiddle is not always so obvious.

JJT in 1979, Radio Headphones Attached To Head

JJT in 1979, Radio Headphones Attached To Head

Now, decades later, I recognize the devil’s modern tactics. He doesn’t offer golden fiddles; he offers something far more insidious: victory through social media battles, comfort in material possessions, the illusion of earned entitlement, and the seductive power of self-righteousness. He whispers that our conflicts are righteous wars against inherently evil enemies, twisting scripture to justify aggression. He plants seeds of resentment and cultivates a hunger for vengeance, eroding empathy and dehumanizing those we perceive as opponents. He encourages echo chambers, dismissing any information that challenges pre-conceived biases. The call to turn the other cheek or embrace sacrifice fades into abstract philosophy, while self-preservation and self-promotion become “practical” necessities, even political virtues. The golden fiddle of temptation is offered not in one grand gesture, but in a million tiny, seductive pieces.

The real danger of epic narratives like the Faustian legend, and even the narrative of the “georgia devil song”, lies in their capacity to distract us from the mundane, everyday soul-selling compromises we make.

When Charlie Daniels introduced “The Devil Went Down To Georgia” as his Cornerstone finale, he declared, “You can’t beat the devil without the Lord. So let’s get together and give him a fit right now.” While an energetic setup for his most famous “georgia devil song”, it still misses the deeper point. Beyond the urban vs. rural, disco vs. country culture war undertones, Johnny’s fatal flaw is hubris. He loses the moment he accepts the devil’s challenge, believing he can win on his own merit. In this, Daniels unwittingly captures a key aspect of the American character, and perhaps, the contemporary church. Like Johnny, we often believe we can defeat the devil by engaging in his games, on his terms.

Even as a child, listening to that “georgia devil song”, I envisioned the devil slinking away at the song’s climax, defeated when Johnny boasts, “I told you once, you sonofabitch, I’m the best there’s ever been!” But perhaps, the devil’s retreat was not one of defeat, but a knowing smile. He understood that Johnny’s pride, his very declaration of being “the best,” was the real victory for the forces of darkness.