David Bowie’s “Fantastic Voyage” might be a lesser-known track from his extensive catalog, but it holds a significant place, potentially marking his last ever stage performance. This song, the opening track of the album Lodger, surprisingly works as both a beginning and an end, encapsulating a poignant and somewhat cynical outlook on the world. It serves as a powerful statement from Bowie, a cranky yet humanist perspective delivered through an unconventional pop song.

A Shift in Tone: From Detachment to Grounded Observation

“Fantastic Voyage” marks a notable departure in tone from Bowie’s earlier Berlin Trilogy and Station to Station era. Gone is the detached observer; Bowie now positions himself firmly on the ground, a part of humanity, acknowledging his own limitations. He transforms into an observer, making wry comments on the state of the world, sounding simultaneously warmer and less calculated. The song allows raw, volatile emotions to surface, creating a sense of immediacy and vulnerability rarely found in his previous work.

Where Bowie once seemed to embrace the potential for transformation within an apocalypse, “Fantastic Voyage” reveals a more mature, perhaps disillusioned, perspective. He appears older, more world-weary, and openly frustrated. Lines like “think of us as fatherless scum” express a stark realism, acknowledging the precariousness of human existence under the rule of “killers and fools.” This peasant realism underscores the arbitrary nature of power and the fragility of peace.

Cold War Angst: The Song’s Context and Influence

The catalyst for this shift seems to be the resurgence of Cold War tensions in 1979, the year of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. This period marked the beginning of the final, intensified phase of Cold War anxieties – the era of MX missiles, Reagan’s alarming jokes, and tragic incidents like the downing of Korean Air Lines Flight 007. “Fantastic Voyage” emerges as a harbinger of the wave of early 80s Cold War protest songs, anthems of youth rising against bellicose politicians. It foreshadows tracks like Young Marble Giants’ “Final Day,” XTC’s “Living Through Another Cuba,” Prince’s “1999,” The Fixx’s “Stand or Fall,” and Alphaville’s “Forever Young,” even resonating with the German protest song “99 Luftballoons.”

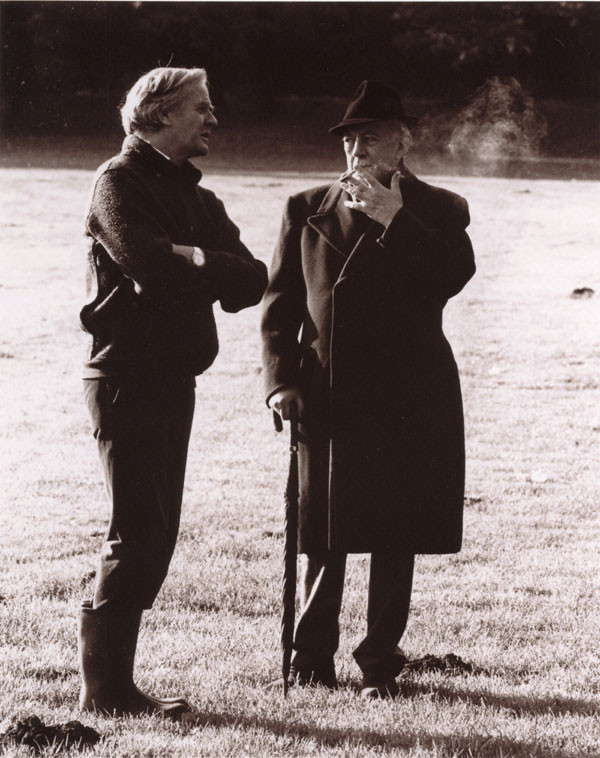

John le Carré and Alec Guinness on the set of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, 1979, reflecting the Cold War atmosphere of the era that influenced David Bowie's Fantastic Voyage song.

John le Carré and Alec Guinness on the set of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, 1979, reflecting the Cold War atmosphere of the era that influenced David Bowie's Fantastic Voyage song.

Bowie’s lyrics are laced with irony from the outset. The opening line, “We never get old,” typically a romantic sentiment in love songs, is twisted into a grim observation of potential mass destruction. The formal, almost stilted delivery of lines like “dig-ni-ty is val-u-a-ble” further emphasizes this unsettling irony. The song’s emotional landscape shifts from resignation to anger and back, maintaining a sense of underlying absurdity. The line “It’s a criminal world, it’s a very modern world” encapsulates this bleak yet realistic view. The backing vocals, provided by Bowie and Tony Visconti, try to inject urgency, with lines like “They wipe out an entire race! It won’t be forgotten!” Yet, the singer’s response is muted, limited to writing lyrics, turning his anxieties into a pop song – a perhaps futile, but ultimately human, act.

Musical Innovation and Structure: Deconstructing “Fantastic Voyage”

“Fantastic Voyage” is an unconventional pop song. While sharing the same key and a similar chord sequence with “Boys Keep Swinging,” it feels far less conventional. The song structure is built around two verses and two choruses, but even these familiar elements are fractured. The verses are loosely structured, with fragmented rhymes, and the chorus initially offers a bouncy refrain—”We’re—/learning to live with somebody’s depression“—before dissolving into repetition and a dry, almost sarcastic joke. The melody fragments, the song seemingly stalls on an A major chord, and Bowie’s vocals intertwine with the backing vocals, creating tension that ultimately resolves with a musical release. The piano, bass, and drums accelerate, while Bowie’s vocals ascend nearly an octave, holding the final note for two bars.

The song’s cohesion relies heavily on Sean Mayes’ piano and George Murray’s bass lines, while Carlos Alomar and Dennis Davis’ drums act as supporting elements. A distinctive feature is the three-mandolin arrangement, a result of Tony Visconti’s late-night inspiration fueled by tequila. Bowie reportedly had to dispatch his driver to find mandolins in Montreux. These mandolins, played by Visconti, House, and Adrian Belew, were triple-tracked, resulting in a total of nine mandolin parts. However, in a deliberate act of sonic perversity, this intricate arrangement is almost buried in the mix, its complexities only truly revealed through headphones.

Legacy and Last Performances

Recorded in September 1978 in Montreux and March 1979 in New York City, “Fantastic Voyage” was released as the B-side to “Boys Keep Swinging” in April 1979. Despite its B-side status, it gained renewed prominence in Bowie’s later years, becoming a staple of his tours in 2003-2004. Significantly, it was the last song David Bowie performed live at the Black Ball in NYC on November 9, 2006, preceding a duet with Alicia Keys on “Changes.” This final performance underscores the song’s powerful and perhaps unintended role as a concluding statement in Bowie’s live career.

“Fantastic Voyage” remains a compelling and complex work, reflecting the anxieties of the Cold War era while offering a timeless meditation on human vulnerability and resilience. Its unconventional structure and layered instrumentation, combined with Bowie’s evocative lyrics and performance, solidify its place as a unique and important song in his vast and influential body of work.