By Wayne Erbsen

I’ve always been drawn to the charm of a good cowboy song. This isn’t because I grew up on a sprawling Texas ranch; my roots are actually in Southern California. During my childhood in the late 40s and early 50s, I was immersed in television westerns like Hopalong Cassidy, The Lone Ranger, Maverick, Rawhide, The Rifleman, Bonanza, and Have Gun – Will Travel. Even before TV, I was captivated by The Lone Ranger and Gunsmoke on the radio. Movies like Shane and High Noon were also among my favorites, shaping my early appreciation for the genre.

Gene Autry with an acoustic guitar

Gene Autry with an acoustic guitar

Of course, I also watched films starring Gene Autry, the iconic singing cowboy. While I enjoyed some of his songs, like Back in the Saddle Again, I found him a bit too polished for my taste. His pristine white hat and impeccably starched shirts never seemed to gather any trail dust. I don’t recall any gritty gunfights in his shows, and predictably, he always won the heart of the pretty girl at the end. That last part always bothered me. I preferred my western heroes a little rougher around the edges, unlike Gene Autry, who always appeared perfectly groomed.

Discovering “Diamond Joe” Through Ramblin’ Jack Elliott

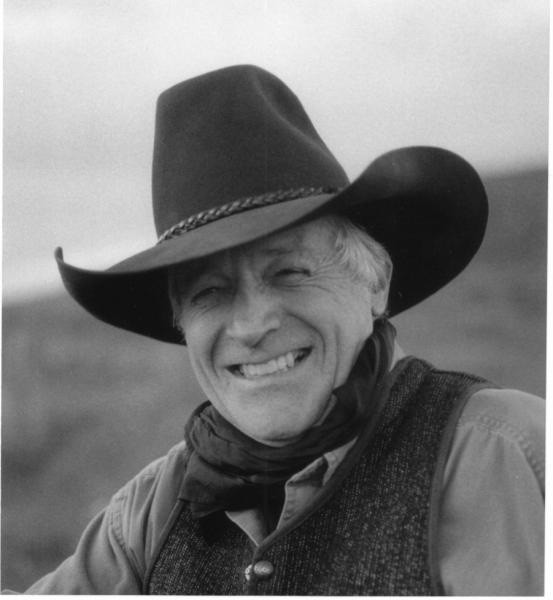

In the early 1960s, the folk music wave swept me away, and I was thoroughly captivated. One of my favorite artists from that era was Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. To me, he embodied the perfect blend of cowboy and folksinger. Among his repertoire, Diamond Joe stood out. I quickly learned it and have been performing it ever since. Years later, I stumbled upon an LP by the old-time group, the Georgia Crackers, featuring a completely different song also titled Diamond Joe. Jack Elliott’s version lacked a chorus, so I decided to merge the chorus of the Georgia Crackers’ song with Elliott’s Diamond Joe. This is how I perform it today, a blend of two distinct traditions.

Ramblin

Ramblin

Recently, while singing Diamond Joe around the house, my wife Barbara overheard the chorus (“Diamond Joe come and get me, my wife now done quit me”). She inquired, “Why did his wife quit him?” The song offers no clear explanation, so I speculated that perhaps Joe was an idle, unkempt, and unreliable cowboy, prompting his wife to seek a better life elsewhere.

Tracing the Origins of Jack Elliott’s “Diamond Joe”

This conversation about Diamond Joe reminded me of research I had conducted years ago into the origins of Jack Elliott’s version. With the help of Nick Hawes, I traced the song back to his father, Baldwin ‘Butch’ Hawes, husband of Bess Lomax Hawes, sister of Alan Lomax and daughter of John Lomax. Nick revealed that Butch wrote the song in 1944 in New York City for a BBC radio program called The Chisholm Trail.

Alan’s wife, Elizabeth, penned the script, drawing inspiration from songs in the Lomax collections. The central character was a tough figure named “Diamond Joe Chisholm.” Elizabeth, not musically trained, inadvertently selected a stately melody in 3/2 meter transcribed by Ruth Crawford Seeger, Pete Seeger’s stepmother. Realizing the tune was unsuitable, it was too late to revise the script.

This led her to Bess Lomax Hawes, the program’s music director. Bess then commissioned her husband, Butch, to compose a new Diamond Joe song that better fit the narrative. Hawes based the melody on State of Arkansas, a song he knew Lee Hays of the Almanac Singers, who was to perform it, had been singing for years.

Cisco Houston, also in The Chisholm Trail cast, was unaware of Butch’s composition and assumed Diamond Joe was an authentic old cowboy song. In 1952, Cisco recorded it for Folkways Records on Cowboy Ballads (FA 2022). In 1954, the lyrics Cisco sang were published in Sing Out! magazine, further cementing its perceived authenticity.

Later, rodeo cowboy George Williams reportedly heard Diamond Joe from Cisco’s record and taught it to Jack Elliott at a rodeo in Brussels, Belgium, in 1958. It became a signature song for Jack Elliott, and that’s how I came to learn it.

Cisco Houston’s Lyrics of “Diamond Joe”

Here are the lyrics Cisco Houston sang, which capture the essence of the hardworking cowboy’s lament:

There is a man you’ll hear about most every place you go.

And his holdings are in Texas, and his name was Diamond Joe

Well he carried all his money in a diamond-studded jaw

And he never was much bothered by the process of the law.

Well I hired out to Diamond Joe, boys, I did offer him my hand

And he gave me a string of horse so old they could not stand

Well I liked to died of hunger, he did mistreat me so.

I never earned a dollar in the pay of Diamond Joe.

Well his bread it was corn dodger and his meat I could not chaw,

And he drove me near distracted with the wagging of his jaw

And the telling of his stories, I’d like to let you know.

There never was a rounder that lied like Diamond Joe.

Well I tried three times to quit him, boys, but he did argue so,

That I’m still punching cattle in the pay of Diamond Joe.

And when I’m called to Heaven, and it comes my time to go

Give my blankets to my buddy, and give the fleas to Diamond Joe.

The Georgia Crackers’ “Diamond Joe” and its Deeper Roots

The other Diamond Joe song, performed by the Georgia Crackers, has its own fascinating history. First recorded for Okeh Records on March 21, 1927, by Paul and Leon Cofer, billed as the Georgia Crackers, it presents a different narrative. I had always sung the chorus of this Diamond Joe as:

Diamond Joe, come and get me

My wife she done quit me.

However, after closer listening to their recording, I realized I had misheard it for years. The actual lyrics are:

Diamond Joe, come and get me,

My wife died and quit me.

This revelation answered my wife’s initial question – the wife didn’t leave, she passed away.

But what does “Diamond Joe, come and get me” truly mean? There’s conflicting evidence. Fragments of lyrics from this original Diamond Joe were published in the Journal of American Folklore, collected from African-American sources in Mississippi in 1909 by Professor E.C. Parrow from a Mister Turner. The chorus in this version is:

Diamond Joe, Diamond Joe

Run get me Diamond Joe.

Several verses from Turner’s version are nearly identical to those sung by the Georgia Crackers in 1927. Here are examples from Mister Turner’s version, with the Georgia Crackers’ verses in parentheses:

Then I’ll buy me a bar ‘el of flour

Cook and eat it every hour.

(Gonna buy me a sack of flour,

Cook me a hoecake every hour).

Yes, an’ buy me a middlin’ o’ meat,

Cook and eat it twick a week.

(I’m gonna buy me a piece of meat,

Cook me a slice once a week).

In 1911, Professor Howard W. Odum published an article in the Journal of American Folklore featuring a version of Diamond Joe from a woman’s perspective:

Diamon’ Joe, you better come an’ git me’

Don’t you see my man done quit,

Diamon’ Joe you better come git me.

Diamon’ Joe he had a wife, they parted every night;

When the weather it got cool,

Old Joe he come back to that black gal.

But time come to pass,

When old Joe quit his last,

An’ he never went to see her any mo’.

“Diamond Joe” the Steamboat?

Finally, we arrive at another potential origin of “Diamond Joe.” Old-time music researchers Gus Meade and Lyle Lofgren uncovered evidence suggesting “Diamond Joe” wasn’t a person at all. Instead, “Diamond Joe” was a steamboat line operating from 1862-1910. According to this interpretation, the weary cowboy in the song is longing for the steamboat to come and take him away from his troubles.

Digging deeper, I found that Joseph Reynolds (1819-1891), a Chicago grain dealer, used a logo of JO inside a diamond. He eventually built a steamboat, named the Diamond Jo, to transport freight on the upper Mississippi River from St. Paul to St. Louis. This could very well be the Diamond Jo the cowboy in the song implores to “come get him.”

It’s interesting to note that Bob Dylan recorded the Georgia Crackers’ version of Diamond Joe, while musicians Laurie Lewis and Joe Val both learned it from Ramblin’ Jack Elliott’s recording, showcasing the song’s diverse journey through musical traditions.

********

Wayne Erbsen has authored over thirty bluegrass music instruction books and songbooks for banjo, mandolin, fiddle, and guitar, along with historical and folklore books and songbooks.

Share this:

No related posts.