Buddy Holly remains an iconic figure in the history of rock and roll music. Though his career was tragically cut short, the body of work he left behind continues to inspire and influence musicians and captivate audiences worldwide. This article delves into the world of Buddy Holly Songs, examining not just his hits but the context of his career, culminating in the fateful events surrounding his untimely death. We’ll explore the journey behind tracks like “It Doesn’t Matter Any More,” a poignant song that became a posthumous hit and a symbol of his lasting impact.

A jukebox, with the words

A jukebox, with the words

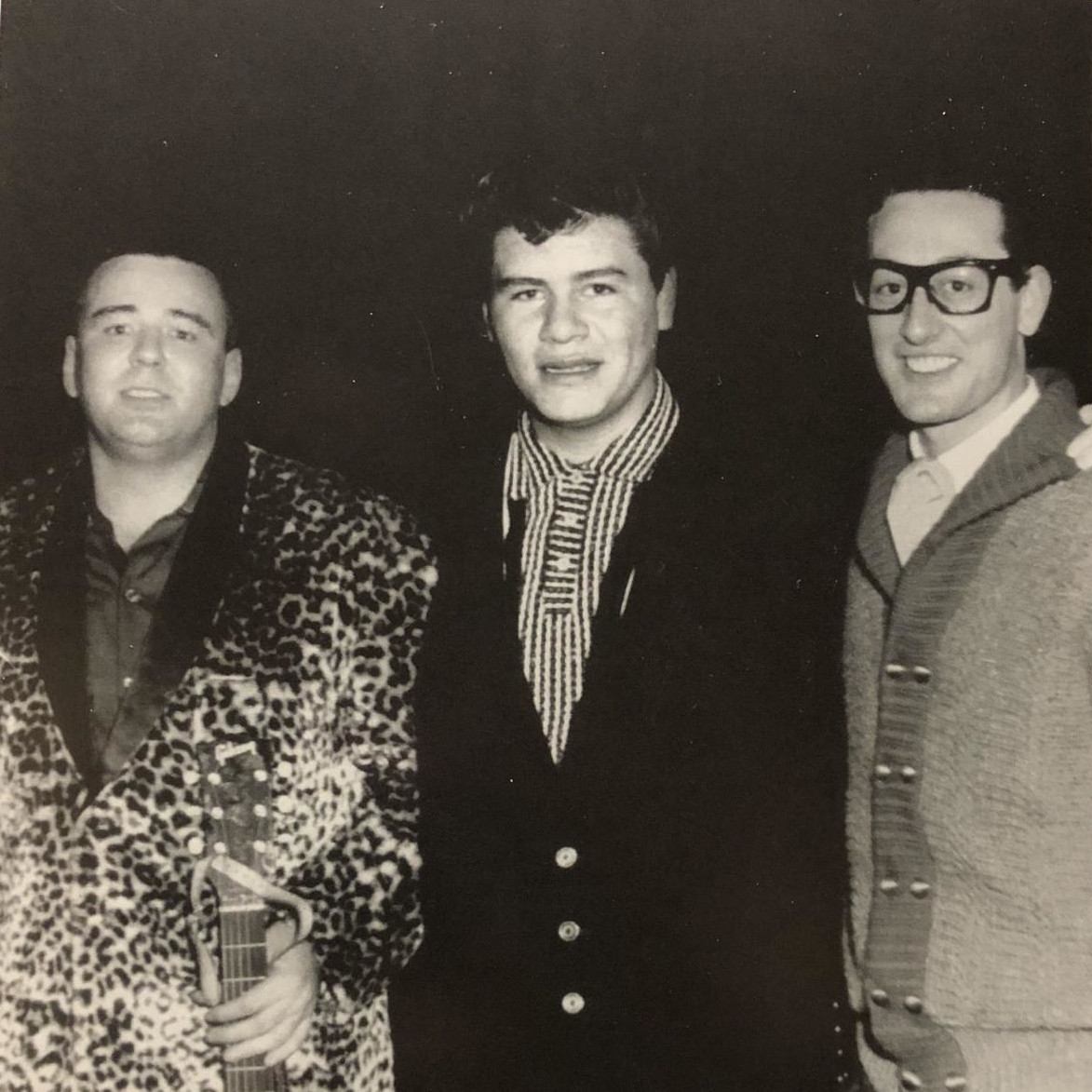

“It Doesn’t Matter Any More” is often labeled as rock and roll’s first posthumous hit, a somewhat inaccurate but deeply symbolic designation. While Johnny Ace’s “Pledging My Love” preceded it, Buddy Holly’s death, alongside Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper, resonated powerfully with the public, cementing “It Doesn’t Matter Any More” as a poignant marker in music history. The tragedy amplified the emotional weight of Buddy Holly songs, adding layers of meaning to his already evocative music.

Even those unfamiliar with the specifics of Buddy Holly songs often recognize two defining traits: his signature glasses and the plane crash that claimed his life. This event, often referred to as “The Day the Music Died,” overshadows his vibrant career, yet understanding the circumstances leading to that fateful flight reveals a darker side of the music industry in the late 1950s – one driven by exploitation and relentless pressure on young artists.

The Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens, and Buddy Holly

The Big Bopper, Ritchie Valens, and Buddy Holly

This exploration of Buddy Holly songs will trace the story of “It Doesn’t Matter Any More,” not just as a song but as a final chapter in a career brimming with creativity and potential, tragically curtailed by circumstances rooted in industry exploitation.

The Meteoric Rise of Buddy Holly and The Crickets

While Buddy Holly’s overall career was brief, his chart-topping success was even more concentrated. His first hit, “That’ll Be the Day,” arrived in May 1957, and within a year, his last top 30 single, “Think it Over,” was released in May 1958. By January 1959, as he embarked on the ill-fated Winter Dance Party tour, hits were no longer guaranteed. His recent release, “Heartbeat,” stalled at number 82. Professional relationships had fractured, and he had parted ways with The Crickets, the band instrumental in his initial fame. To grasp this turning point, we need to rewind to the initial success of Buddy Holly songs with The Crickets.

Initially, the lines between Buddy Holly’s solo work and The Crickets were blurred. The same musicians – Buddy Holly, Niki Sullivan, Jerry Allison, Joe Mauldin, and producer Norman Petty – recorded tracks regardless of the credited artist. Later, the distinction emerged: more straightforward rock and roll tunes with backing vocals (often by The Picks) were released as Crickets songs, while more experimental recordings, featuring primarily Holly’s vocals, appeared under his solo name. This strategy aimed to maximize airplay, presenting DJs with seemingly different artists.

The period was incredibly productive. In a flurry of creativity, they recorded a string of songs within a short timeframe, including “Everyday,” “Not Fade Away,” “Tell Me How,” “Oh Boy,” “Listen to Me,” “I’m Going to Love You Too,” and covers of “Valley of Tears” and “Ready Teddy,” all before “That’ll Be the Day” and “Words of Love” even charted.

“Peggy Sue”: A Defining Buddy Holly Song

The breakthrough arrived on July 2nd with a re-recording of “Peggy Sue,” originally titled “Cindy Lou.” Jerry Allison’s budding romance with Peggy Sue Gerrison inspired the lyrical shift. Initially a Latin-flavored tune, the song transformed when Allison’s snare drum paradiddle during a warm-up caught Holly’s ear. The tempo shifted, and Allison’s drumming became central, requiring him to play in the hallway due to the studio’s acoustics. Petty’s echo effect on the drums intro added another layer of sonic innovation.

[Excerpt: Buddy Holly, “Peggy Sue”]

“Peggy Sue” showcased the innovative spirit that defined Buddy Holly songs. Niki Sullivan’s role on “Peggy Sue” became unconventional, acting as a manual guitar switch during Holly’s solo, highlighting the band’s resourcefulness and Holly’s intense performance style. The stripped-down sound of “Peggy Sue,” driven by voice, drums, and guitar solo, revealed Holly’s unique musical vision.

Tensions and Triumph: The Crickets’ Journey

Despite the success, tensions simmered within The Crickets. Sullivan felt sidelined, and personal conflicts arose, including Holly’s affair, which strained his friendship with Allison. A fishing trip with his brother Larry offered a temporary escape, but even there, Holly’s anxieties about chart success and the rise of artists like Paul Anka were evident.

Then, unexpectedly, “That’ll Be the Day” gained traction on black radio stations. Mistakenly identified with a previous black doo-wop group also called The Crickets, the stations discovered the song’s appeal. This led to bookings on predominantly black tours, including a challenging performance at the Apollo Theater in Harlem, where they had to adapt their set, emphasizing R&B covers alongside “That’ll Be the Day” to win over the initially resistant audience.

Following this tour, a residency at the Brooklyn Paramount alongside Little Richard and Larry Williams further intensified band dynamics. Sullivan’s revelation about Holly’s affair to Allison sparked a physical altercation, reportedly resulting in Sullivan giving Allison a black eye, just before a photo shoot for their debut album, The “Chirping” Crickets.

Despite internal strife, their musical trajectory soared. “That’ll Be the Day” reached number one, “Peggy Sue” climbed to number three, and “Oh Boy!” another hit, written by Sonny West, followed.

[Excerpt: Sonny West, “All My Love”]

[Excerpt: The Crickets, “Oh Boy!”]

Eddie Cochran and The Everly Brothers joined them on tour, forging strong bonds. A performance on The Ed Sullivan Show further cemented their national recognition. However, Sullivan’s diminishing role and tour-related stress led to his departure from The Crickets.

Niki Sullivan’s Exit and Norman Petty’s Influence

Sullivan’s attempt at a solo career with “It’s All Over” proved unsuccessful.

[Excerpt: Niki Sullivan, “It’s All Over”]

He later entered the electronics field and eventually participated in the Buddy Holly nostalgia circuit. His tenure with The Crickets, though brief in touring days, was significant in studio contributions, playing on the majority of Buddy Holly songs released during Holly’s lifetime. Financial disputes with manager Norman Petty, who controlled the band’s finances and fostered divisions, further complicated Sullivan’s experience.

Petty’s manipulative tactics extended to restructuring The Crickets, positioning Buddy Holly as the frontman with a backing band, altering financial splits to Holly’s benefit but ultimately controlling the group’s earnings. Tommy Allsup joined as a guitarist, further shifting the band’s dynamics. While Buddy Holly songs like “It’s So Easy” were still being recorded, their chart performance began to wane.

[Excerpt: The Crickets, “It’s So Easy”]

Marriage and Shifting Priorities

A visit to New York brought a significant personal change for Holly. He met Maria Elena Santiago, a receptionist at their publisher’s office, and proposed on their first date. Maria Elena, with her music industry experience and maturity, encouraged Holly to scrutinize his financial arrangements with Petty. This advice strained Holly’s relationship with his manager, who resented Maria Elena’s involvement.

Relocating to Greenwich Village with Maria Elena, Holly remained contractually tied to Petty, despite the growing friction. Experimentation marked this period, with ventures like Jerry Allison’s lead vocal on “Real Wild Child” (released as “Ivan”) and collaborations with King Curtis on saxophone, exploring new sonic territories beyond typical Buddy Holly songs.

[Excerpt: Ivan, “Real Wild Child”]

[Excerpt: Buddy Holly, “Reminiscing”]

A Bobby Darin cover, “Early in the Morning,” further showcased his willingness to explore different musical avenues. However, these releases didn’t achieve significant chart success. Holly also produced Waylon Jennings’ first recording session, revealing his collaborative spirit and interest in diverse musical styles, blending Cajun and R&B influences in their version of “Jole Blon.”

[Excerpt: Waylon Jennings, “Jole Blon”]

“It Doesn’t Matter Any More”: A New Sound and Final Recording

Holly’s ambition led him to a groundbreaking session in October 1958, recording with the Dick Jacobs Orchestra – a first for a rock and roll artist at the time. He planned to record “True Love Ways,” “Moondreams,” and “Raining in My Heart.” At the last minute, he added “It Doesn’t Matter Any More,” a song penned by Paul Anka. Dick Jacobs quickly arranged the song, emphasizing pizzicato violins.

[Excerpt: Buddy Holly, “It Doesn’t Matter Any More”]

This session, which produced “It Doesn’t Matter Any More” and other tracks, marked a departure from the typical Buddy Holly songs sound, showcasing his evolving musicality and willingness to experiment with orchestral arrangements. The Crickets and Petty were present, seemingly supportive. The Crickets’ American Bandstand performance miming to “It’s So Easy” that night became their final performance together.

The Split, Financial Crisis, and Winter Dance Party

Holly’s dissatisfaction with Petty’s financial dealings reached a breaking point. He planned to confront Petty, reclaim owed royalties, and relocate to New York with The Crickets to launch their own label and publishing venture. This plan hinged on recovering the funds controlled by Petty.

However, Petty manipulated Mauldin and Allison, convincing them to remain in Texas, questioning their suitability for New York, downplaying Holly’s importance, and suggesting Maria Elena’s undue influence. He also hinted at the precariousness of the band’s finances if they sided with Holly, as he controlled their bank account.

Upon Holly’s return to Texas, The Crickets sided with Petty. Petty severed Holly’s financial access, demanding a full audit before releasing any funds. Holly returned to New York facing a financial crisis.

Despite the setback, Holly entered a period of intense creativity, writing numerous songs and recording acoustic demos, envisioning future projects, including Latin music, gospel duets with Mahalia Jackson, and soul collaborations with Ray Charles. He explored jazz clubs and even enrolled in Lee Strasberg’s Actors Studio, pursuing acting ambitions. Greenwich Village in 1958 became a fertile ground for his artistic exploration.

However, financial strain mounted, especially with Maria Elena’s pregnancy. Petty then revealed a devastating clause in Holly’s contract: he had been recording for Petty’s company, not Brunswick or Coral, meaning royalties were owed to Petty, and the Crickets’ bank account was virtually empty.

Touring became the only viable option. Holly joined the Winter Dance Party, a tour characterized by grueling conditions and logistical nightmares. Alongside Frankie Sardo, Dion and the Belmonts, the Big Bopper, and Ritchie Valens, the tour routed through the frigid Midwest in January and February 1959.

The tour conditions were appalling. Constant travel in poorly heated buses across vast distances in sub-zero temperatures, inadequate sleep, and widespread illness plagued the musicians. Carl Bunch, Holly’s drummer, was hospitalized with frostbite. Holly, Dion, and Valens rotated drumming duties to keep the shows going. A young Bob Dylan witnessed one of these drummerless performances in Duluth, Minnesota.

After a show in Clear Lake, Iowa, Holly chartered a plane to Fargo, North Dakota, seeking respite from the tour’s hardships – laundry, sleep in a bed, and a break from the freezing buses. Allsup and Jennings were initially meant to join him, but they gave their seats to the ailing Big Bopper and Valens. A fateful exchange occurred: Holly jokingly told Jennings, “I hope your old bus freezes,” and Jennings replied, “Yeah, well I hope your ol’ plane crashes.”

The Day the Music Died

In the early hours of February 3, 1959, the plane carrying Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper crashed shortly after takeoff in foggy, winter conditions, killing all aboard instantly. Pilot error, possibly exacerbated by a confusing altimeter in the plane, is considered the primary cause.

News of the tragedy spread rapidly, and “It Doesn’t Matter Any More” began its ascent on the charts, reaching number 13 in the US and number one in several other countries, becoming a poignant posthumous hit.

The aftermath of the crash highlighted the industry’s callousness. Maria Elena learned of Buddy’s death from a television report, not official notification, leading to changes in celebrity death announcements. Distraught, she miscarried two days later and has never visited his grave. The remaining tour members were forced to continue, receiving reduced pay.

Bobby Vee, a young Holly lookalike, was quickly recruited to fill the void.

[Excerpt: Bobby Vee, “Suzy Baby”]

Bobby Vee later hired a young Elston Gunn (Bob Dylan) as his piano player. Fabian, Frankie Avalon, and Jimmy Clanton replaced Holly, Valens, and the Bopper on the tour.

The Crickets continued, recruiting Sonny Curtis and various Holly-esque singers, remaining active until Joe Mauldin’s death in 2015. They achieved some success, notably with “I Fought the Law,” later a hit for others.

[Excerpt: The Crickets, “I Fought the Law”]

Norman Petty profited immensely from Holly’s death, exploiting unreleased recordings and demos, overdubbing them to create posthumous hits well into the 1960s, enriching himself and Holly’s estate. Petty’s last project involved synthesizer-heavy “updates” of Buddy Holly songs.

In a final, perhaps unsettling, chapter, Buddy Holly is now “touring” again as a hologram, a spectral image miming to his recordings, highlighting the enduring commercial exploitation of his legacy.

Discover more from A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.