Blink-182, the kings of pop punk irreverence, once penned a song that dared to be deeply, unironically sad. In a genre known for its upbeat tempos and lyrical winks, “Adam’s Song” emerged as a starkly honest exploration of teenage depression and suicidal ideation. This track, far from being a deviation, became a defining moment for the band and for pop punk itself, proving the genre’s capacity for emotional depth.

From Ironic Detachment to Millennial Sincerity: The Pop Punk Evolution

Early pop punk, exemplified by Green Day, often navigated serious themes with a layer of irony. “Basket Case,” while addressing disorientation and Gen X angst, does so with a self-deprecating humor characteristic of the era. This ironic stance was partly inherent to pop punk’s juxtaposition of upbeat music and melancholic lyrics, and partly a reflection of the prevailing Gen X cynicism seen in figures like Kurt Cobain and shows like Seinfeld.

However, as the torch passed to bands like My Chemical Romance, Paramore, and Fall Out Boy in the 2000s, a shift towards sincerity took hold. These bands, largely resonating with millennial audiences, spearheaded a reaction against Gen X irony. Even Green Day themselves evolved, embracing sincerity with their politically charged album American Idiot (2004). Key singles like Jimmy Eat World’s “The Middle” and Simple Plan’s “Perfect” paved the way, but it was Blink-182’s “Adam’s Song” that delivered the most profound and impactful statement of this evolving emotional landscape.

“Adam’s Song” and Enema of the State: A Rock Music Paradigm Shift

Released as the final single from their landmark 1999 album Enema of the State, “Adam’s Song” stands as a testament to the album’s seismic impact on rock music. Enema of the State wasn’t just an album; it was a cultural reset. It’s not hyperbole to suggest that Enema of the State single-handedly revitalized mainstream rock. As Ian Cohen of Pitchfork noted, alongside albums like The Offspring’s Smash and Green Day’s Dookie, it served as a “beginner’s manual” for aspiring guitarists and bands, igniting a new wave of rock musicians.

blink2

blink2

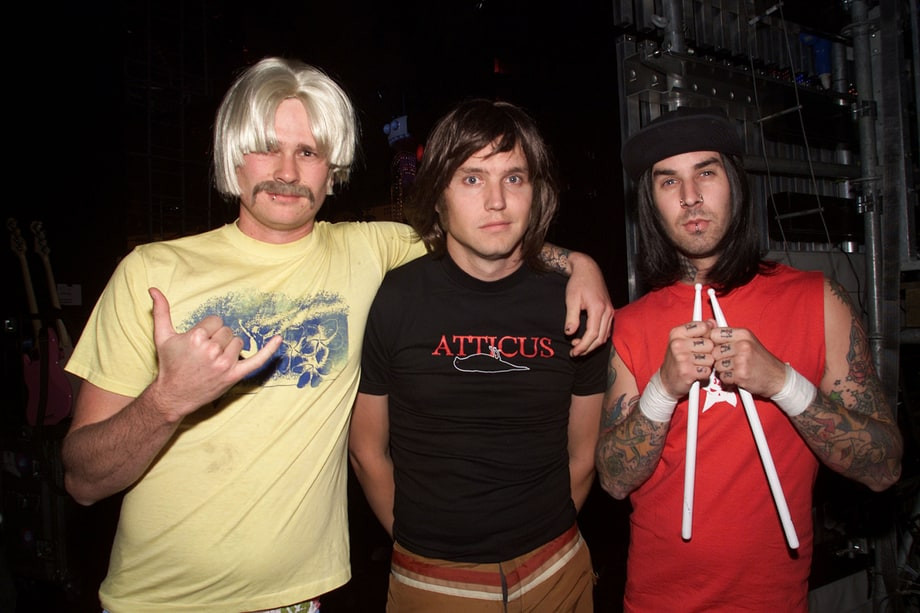

Image alt text: Blink-182 band members Mark Hoppus, Tom DeLonge, and Travis Barker in a promotional shot for Enema of the State, the album featuring Adam’s Song.

The album resonated deeply because it spoke directly to the anxieties and experiences of teenagers and young adults. From the fear of losing youthful joy in “What’s My Age Again?” to the post-high school relationship anxieties in “Going Away to College,” and the overarching dread of a broken world in “Anthem,” Enema of the State validated the profound feelings of young people. It declared that youth emotions were just as valid and musically compelling as adult concerns, even when packaged with the band’s signature juvenile humor. The album, encapsulated by the lyric “bouquet of clumsy words, a simple melody” from “Going Away to College,” remains a timeless and essential pop culture artifact.

While “What’s My Age Again?” and “All the Small Things” achieved greater commercial success, “Adam’s Song” arguably surpasses them as the album’s most impactful track and perhaps Blink-182’s greatest song.

The Nuance of Darkness: “Adam’s Song” in Blink-182’s Discography

Appreciating Blink-182 means embracing their joyful immaturity. Therefore, it might seem paradoxical to consider “Adam’s Song,” their most serious and somber work, as their pinnacle. Often, within artists known for levity, their serious pieces are automatically elevated as their “most artistic.” Think of Jim Carrey in comedic roles versus dramatic ones, or Charlie Brooker’s comedy versus Black Mirror. However, reducing “Adam’s Song” to simply being “serious Blink-182” misses the point.

“Adam’s Song” is a dark and serious exploration of suicide and depression, presented as a suicide note. Lyrics like “I’m too depressed to go on / you’ll be sorry when I’m gone” and “please tell Mom this is not her fault” are undeniably stark. Yet, the song is interwoven with typically immature Blink-182 elements, like the opening masturbation joke in the chorus (“I never conquered / rarely came”) and the quirky memory of spilled apple juice. This blend isn’t a departure but an extension of their core themes, delving into the darkest corners of teenage experience. “Adam’s Song” directly addresses youth suicide and mental illness, mirroring the broader societal issue. Even a band known for its lightheartedness, to authentically explore teenage themes, inevitably had to confront this darkness, as Bowling for Soup also did with “When We Die.” Enema of the State‘s brilliance lies partly in its willingness to explore this darkness, especially placing “Adam’s Song” between the comedic “Dysentery Gary” and the saccharine “All the Small Things,” highlighting the emotional range within teenage life.

Deconstructing Hope: Lyrics, Drums, and Piano in the Final Chorus

“Adam’s Song”‘s genius lies in its ability to evoke hope not through grand pronouncements, but through subtle musical and lyrical shifts, particularly in the final chorus. This section transcends typical pop punk, achieving a moment of musical transcendence. Let’s examine the layers of this transformation: lyrics, drums, and piano.

Lyrical Transformation: From Despair to Anticipation

The initial choruses paint a picture of despair and longing for a better past:

I never conquered, rarely came

sixteen just held such better days

days when I still felt alive

we couldn’t wait to get outside

the world was wide, too late to try

the tour was over, we’d survived

I couldn’t wait til I got home

to pass the time in my room alone

This chorus is steeped in nostalgia and present-day stagnation. Lines like “days when I still felt alive” and “the world was wide, too late to try” powerfully convey feelings of hopelessness and confinement. The “tour” metaphor works on both personal and relatable levels, representing life’s struggles as a constant, exhausting journey. Had the song ended here, it would be crushingly bleak. However, the final chorus offers a crucial, transformative shift:

I never conquered, rarely came

tomorrow holds such better days

days when I can still feel alive

when I can’t wait to get outside

the world is wide, the time goes by

the tour is over, I’ve survived

I can’t wait til I get home

to pass the time in my room alone

The changes are subtle yet profound. “Sixteen just held such better days” becomes “tomorrow holds such better days,” shifting the focus from a glorified past to a potentially brighter future. “Days when I still felt alive” transforms into “days when I can still feel alive,” injecting a possibility of renewed vitality. The shift from “I couldn’t wait til I got home” to “I can’t wait til I get home” is also crucial. The first implies a desire to escape and isolate, while the latter suggests anticipation, perhaps for solace or simply a change of scenery.

Crucially, the recovery depicted isn’t presented as sudden ecstasy. Modern pop songs about mental health often err by portraying recovery as an immediate, euphoric flip, a point Bo Burnham satirized. Recovery from depression is gradual, not a confetti explosion. “Adam’s Song” avoids this trap. The lyrical shift is modest, mirroring the reality of recovery as a slow, incremental process. Yet, for someone in despair, this subtle shift is monumental, representing the crucial difference between hopelessness and a glimmer of possibility. By not overstating the feeling of recovery, “Adam’s Song” achieves a rare authenticity in songs about mental illness, avoiding the false promises of purely affirmative pop music while offering more hope than purely cynical alternative music.

blink3

blink3

Image alt text: Travis Barker intensely drumming on stage, highlighting his crucial role in Adam’s Song’s emotional impact through rhythmic shifts.

Drumming Dynamics: Building and Releasing Tension

The drums in “Adam’s Song,” masterfully played by Travis Barker, are not just accompaniment; they are the driving emotional force. The guitar and bass provide a deliberately monotonous backdrop, reflecting the cyclical nature of depression. The variations and emotional texture come primarily from Barker’s drumming, specifically his cymbal work, alternating between china, ride, hi-hat, and splash cymbals.

Throughout the song, the drumming builds a subtle tension. In the initial choruses, especially the second half, Barker employs a frustrating drum roll on the last upbeat of every second measure, creating an anticipation that never fully resolves. This rhythmic frustration mirrors the feeling of being trapped in despair, constantly building towards a release that doesn’t come.

In the final chorus, however, this tension is masterfully released. The drum roll shifts to the first three-quarters of the phrase, and then, in the final quarter, Barker unleashes doubled drum rolls on the downbeat. This rhythmic shift provides the cathartic release the song has been subtly promising. The drums finally deliver the “climax” previously withheld, punctuating the hopeful lines “I can’t WAIT til I get HOME / to pass the TIME in my room ALONE.” This rhythmic resolution, combined with the melodic change from “I couldn’t wait” to “I can’t wait,” creates a sense of joyous release, even within the context of a still somewhat mundane ending.

The Piano’s Arrival: An Unforeseen Catalyst for Change

Pop punk and piano have an interesting relationship. The sudden appearance of piano in a pop punk song often signals a moment of seriousness and emotional vulnerability. Blink-182 utilizes it in “Adam’s Song” and “I Miss You,” Fall Out Boy in “Golden,” and My Chemical Romance in “Cancer” and “Welcome to the Black Parade.” The plaintive piano interlude in “Adam’s Song” is a genre highlight.

blink4

blink4

Image alt text: Close up of piano keys, symbolizing the unexpected piano interlude in Adam’s Song and its transformative effect on the song’s emotional trajectory.

Many poorly written songs about mental health offer simplistic, often harmful, advice. They suggest recovery is purely a matter of willpower, ignoring the complexities of mental illness. They perpetuate the damaging myth that mental illness is a personal failing, rather than a complex health issue. “Adam’s Song” avoids this trap.

The piano interlude acts as an unforeseen element, entering the song and initiating a shift. As the piano plays its riff, the guitars, bass, and drums subtly change, building in new ways not heard earlier. When the piano fades, the familiar musical patterns return, but now imbued with a newfound hopefulness, mirroring the lyrical shift. The piano interlude becomes the catalyst, representing an inexplicable turning point between despair and hope. It offers hope without making false promises of a guaranteed cure or instant happiness.

The brilliance of “Adam’s Song” lies in this understated approach to hope and recovery. It doesn’t promise a euphoric future, but simply suggests the possibility of something better. This is crucial because when specific solutions fail, as they often do in mental health treatment, it can deepen despair and self-blame. “Adam’s Song,” by presenting a non-specific, unforeseen element of change, avoids setting up such potential self-attacks.

“Adam’s Song” isn’t a song about guaranteed recovery, but about the potential for recovery, however uncertain. It acknowledges the mundane reality of recovery – not a dramatic transformation, but a gradual process of becoming “just about okay.” And in that honest portrayal of fragile hope, “Adam’s Song” finds its enduring power and continues to resonate deeply with listeners navigating their own journeys through darkness towards a brighter, if still uncertain, horizon. It’s a testament to the song’s genius that even in the “future now,” the hope it offers, however subtle, remains profoundly relevant and comforting.