The first time I encountered Mary Oliver’s collection of poems, Dog Songs, it was serendipitously placed on a coffee table during a visit to the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Despite my immediate recognition that this book, with its evocative title, seemed tailor-made for my interests, the leisurely pace of a weekend getaway filled with coastal walks, art gallery visits at Seagreen Gallery, and relaxed moments, left little time for a proper reading. I departed with a firm intention to purchase my own copy and delve into its pages at my earliest convenience.

That initial discovery occurred in the early months of the year.

Then, as March unfolded, the global pandemic dramatically reshaped our daily lives, delaying our return to the Outer Banks until July. During that summer visit, I managed to read a few poems from the collection, but the ever-present hum of the television and the lively family conversations in the room made it challenging to fully immerse myself in the verses.

Once again, I left with the resolve to acquire my own copy and truly explore its depths.

Mary Oliver's Dog Songs book cover

Mary Oliver's Dog Songs book cover

“There is not a dog that romps and runs but we learn from him…Only unleashed dogs can do that.” — Mary Oliver

August arrived, and I found myself seated on the floor, my knees tucked under my mother-in-law’s coffee table. Dog Songs remained atop the small stack of books, exactly where I had left it the previous month. The family room was peaceful. My dogs, Nacho and Soda, were quietly occupied, gnawing on antlers nearby. I picked up the book and, this time, read through almost the entire collection in one sitting. Compelled by the poems’ resonance, I immediately went online and finally purchased my own copy to properly explore.

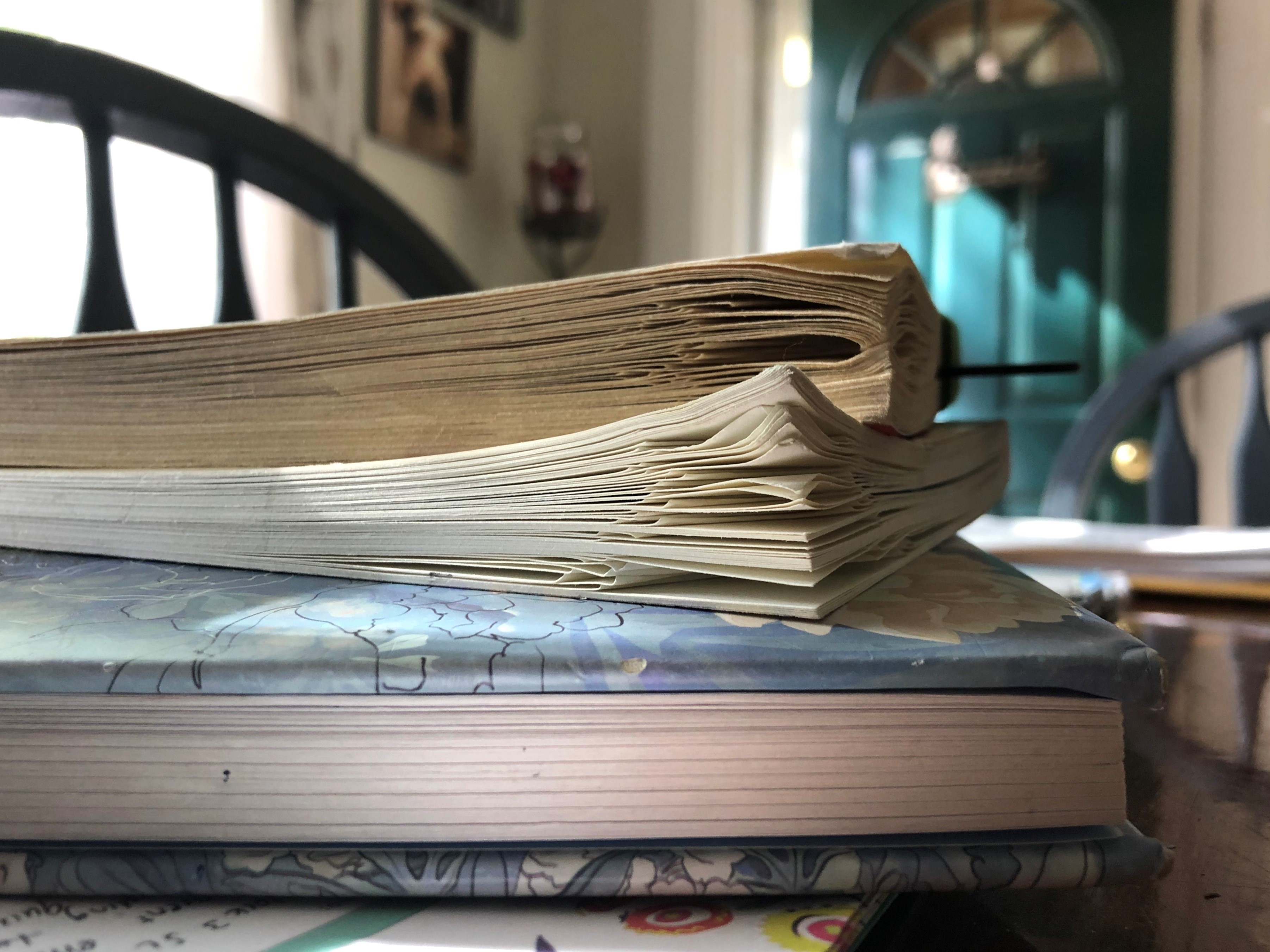

It arrived at my doorstep just three days later. Since then, nearly every page of Dog Songs has been lovingly dog-eared – a fitting fate for a book dedicated to canine companions. I’ve filled the margins with notes, personal memories, ideas, and sparks of inspiration.

This morning, as my husband enjoyed his pancakes, he noticed the book beside my plate on the kitchen table.

“Look at all the pages you’ve dog-eared in Dog Songs,” he remarked. “You must really love that book.”

And indeed, I do. Beyond feeling a sense of kinship with Mary Oliver in our shared affection and understanding of dogs, her poetry collection has evoked a spectrum of emotions within me – laughter, tears, reflection, and remembrance. Here, I found a kindred spirit, someone who perceives and cherishes dogs in the same profound way that I do.

A dog-eared copy of Mary Oliver's Dog Songs book

A dog-eared copy of Mary Oliver's Dog Songs book

Top: My dog-eared copy of Mary Karr’s The Art of Memoir; Middle: My dog-eared copy of Mary Oliver’s Dog Songs; Bottom: my current journal

On a deeper, literary level, I was profoundly impressed by the book’s insightful depth, masked by its seemingly simple language. Oliver’s poem, “For I Will Consider My Dog Percy,” perfectly exemplifies this quality. She describes Percy as “a mixture of gravity and waggery” – an apt description for the book itself, which navigates a range of human and canine emotions, encompassing sorrow, philosophical contemplation, unbridled joy, poignant grief, and simple pleasures. Poems like “The Wicked Smile” and “A Bad Day” inject humor into the collection, while others, such as “Dog Talk,” adopt a more contemplative and sobering tone.

Through her verses, Oliver masterfully articulates the inherent disconnect that can arise between our human-centric expectations of dogs and the very essence of a dog’s true nature. The book’s opening poem, aptly titled “How It Begins,” serves as a foundational piece, setting the stage for the themes explored throughout the collection. It begins with the simple yet profound statement: “A puppy is a puppy is a puppy.” Many poems that follow resonate with this message, emphasizing that a dog remains fundamentally a dog, regardless of our attempts to mold them through selective breeding or rigorous training. In “Her Grave,” Oliver poignantly reminds us, “A dog comes to you and lives with you in your own house,/but you/do not therefore own her, as you do not own the rain, or the/trees or the laws which pertain to them.” Similarly, “Dog Talk” gently admonishes readers, “Dog promises and then forgets, blame him not. He understands what is wanted; and tries, and tries again, and is good for a long time, and then forgets.”

Mary Oliver's Dog Songs book cover displayed on a table

Mary Oliver's Dog Songs book cover displayed on a table

But then one day after I have left this world of particulars, you will look at the face of a little, brown dog and her brother, and you will know– I didn’t take up all the room in your heart; I just made it bigger. –from “This is Love Eternal”

In “A Bad Day,” Oliver playfully imagines a conversation with her dog Ricky, where Ricky retorts, “‘Honestly, what do you expect? Like/you, I’m not perfect, I’m only human.’” This poem, and indeed the entire collection, serves as a gentle reminder that both dogs and humans should be allowed to live authentically, embracing their inherent imperfections. Her poem “School” portrays a dog that might be conventionally labeled as “bad” or “dumb.” The poem’s initial lines depict the speaker’s struggle to command obedience from the dog, who seemingly ignores or misunderstands every instruction, acting “like a little wild thing/that was never sent to school.” However, the poem culminates in an insightful epiphany: “It is summer,” the speaker realizes. “How many summers does a little dog have?/Run, run, Percy. This is our school.” In “Dog Talk,” Oliver powerfully asserts that a dog “that all its life walks leashed and obedient down the sidewalk–is what a chair is to a tree. It is a possession only, the ornament of a human life,” contrasting this with the profound learning available from a dog allowed to explore freely: “There is not a dog that romps and runs but we learn from him…Only unleashed dogs can do that.”

Among the many poems in Dog Songs that resonated deeply with me, as evidenced by the numerous dog-eared pages, “The First Time Percy Came Back” holds a particularly special place. This poem, found on page 77, evokes a powerful emotional response – a blend of tears, smiles, aches, and sighs. It mirrors my own experiences with my dog Jack and his repeated returns, echoing a recent memory of finding a sock on the trail to Fossil Beach in Westmoreland State Park with Matty and the Littles.

Finally, I must comment on the unique layout of the book. Each two-page spread features a blank left-hand page. My initial, pragmatic reaction was to view this as an unnecessary use of paper. However, as I immersed myself in the poems, I discovered the purpose of these blank pages. They became an inviting space for my own creative responses, prompting me to pen my own poems, nestled alongside Oliver’s verses. These empty pages were not wasteful at all; they were an invitation, waiting to be filled with my own inspiration sparked by Oliver’s work. And I have, and undoubtedly will continue to, fill them for a long time to come.

Inspired by Dog Songs, I’ve begun to develop my own poetic works, a few of which are shared below. By now, it should be clear that I wholeheartedly recommend Dog Songs. While I could delve further into the rich symbolism of the unleashed dog, the potent metaphors Oliver employs to convey the lessons dogs impart, and the overarching theme of dogs connecting us to our primal roots, this is, after all, a blog post, not a book-length analysis. Therefore, I encourage you to discover the profound beauty and wisdom of Dog Songs for yourself.

<em><strong>The Adoption</strong></em>

One day, you were hungry and alone--

only you did not know what hunger was,

or what aloneness was--

only that you needed.

Until one day--!

And you never went hungry again,

nor were you alone.

<em><strong>This is Love Eternal</strong></em>

No matter how many years we share,

it will not seem like enough.

And no matter how aware you are

that some day will be our last day,

you will not be ready.

You will not be ready to say goodbye

when I am ready to go.

And yet this does not stop us from starting.

And this is love eternal, though time is limited.

But it was never about how you would feel losing me--

only about you what you could give me.

I know that.

You will feel like you let me down

and wonder why you didn't do better;

you will feel like there's a hole in your heart,

an emptiness in your day.

It is an end you know will bring sorrow,

but it is unselfish and glorious and beautiful,

and no sorrow is deep enough to steal this love.

For this is love eternal, though time is limited.

And sometimes you will look at me and,

thinking it impossible, you will wonder

how you will ever love another dog

this much or this way again.

But then one day after I have left this world of particulars,

you will look at the face of a little, brown dog and her brother,

and you will know--

I didn't take up all the room in your heart;

I just made it bigger.

<em><strong>Roommates with God</strong></em>

My husband said living with Jack was like being roommates with God.

And in the way that God is unconditional, ever-present love--

that is true.Sumo Says Goodbye

There’s not a clear cell signal here, but there’s a clear view of the milky way.

And here it is that Saturday morning, we laid Sumo to rest beside Smokey and Baxter, under trees, where crickets chirp all day long in the perpetual twilight of the shade.

He died Friday afternoon, outside in front of the house on Goddin Street.

That very day I’d been thinking Sumo probably had several more years left, just plugging along like he had been.

On Wednesday, Matty’s birthday, we saw him for the last time. He’d become so low-maintenance, he was almost a non-entity. He would greet us and was then happy just to sleep on the floor in the room where everyone was, sometimes staying there long after we’d switched locations, maybe not knowing we’d moved, maybe his near-blindness and near-deafness hiding our departure from him.

And now he has departed from us, as quietly and invisibly as we had from him a hundred times before, not saying goodbye, not wanting to stir him from his slumber.

And now we are as surprised at his departure–taken so as not to disturb us–as he, waking up to find himself alone, must’ve been at ours a hundred times before.

© Amanda Sue Creasey