“Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” is a song instantly recognizable for its cheerful melody and uplifting lyrics. Many know it from Disney parks or classic sing-alongs, but the story behind this seemingly simple tune is far more complex and rooted in a controversial past. Understanding this background enriches our appreciation – and perhaps complicates it – of this Oscar-winning song.

The Oscar-Winning Song from a Controversial Film

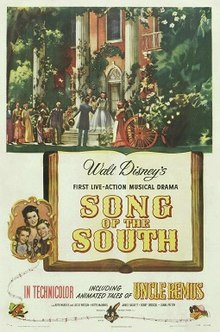

In 1947, “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” won the Academy Award for Best Original Song. It was featured in the 1946 Disney film Song of the South, performed by James Baskett, a Black actor playing the character Uncle Remus. This film is notable for its blend of live-action and animation, but even more so for Disney’s long-standing reluctance to release the complete movie in the United States on home video or digital platforms. While segments can be found online, the full film remains largely inaccessible, shrouded in controversy.

Song of the South movie poster featuring Uncle Remus and animated characters, highlighting the film's connection to the song Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.

Song of the South movie poster featuring Uncle Remus and animated characters, highlighting the film's connection to the song Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.

The reason for Disney’s vaulting of Song of the South lies in its depiction of the American South and race relations. As the NAACP stated upon the film’s release, while acknowledging its artistic merit, the movie presented “a dangerously glorified picture of slavery… [the film] unfortunately gives the impression of an idyllic master-slave relationship which is a distortion of the facts.” This criticism highlights the film’s setting, which appears to be a post-Civil War plantation where Black workers, including Uncle Remus, seem content and subservient, with no acknowledgement of the brutal realities of slavery and racial inequality.

Interestingly, at the time, some voices defended the film. Hattie McDaniel, the acclaimed actress, stated, “If I had for one moment considered any part of the picture degrading or harmful to my people I would not have appeared therein.” James Baskett himself echoed this sentiment, believing that “certain groups are doing my race more harm in seeking to create dissension than can ever possibly come out of the Song of the South.” Despite these defenses, the prevailing view today recognizes the film’s problematic portrayal of history.

“Song of the South” and its Contentious Legacy

The film employs a framing device: a young white boy visiting his grandmother in the South is comforted by Uncle Remus, who tells him animated stories featuring Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox, and other animal characters derived from the Uncle Remus stories by Joel Chandler Harris. These animated segments, introduced and concluded by “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” are interspersed with the live-action narrative. The ambiguity surrounding the timeline, whether pre- or post-Civil War, further complicates the film’s representation of race and the plantation setting. The cheerful song, therefore, is inextricably linked to this complex and debated cinematic work.

From Minstrel Shows to Disney: The Song’s Surprising Origins

Beyond the immediate context of Song of the South, “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” has even deeper roots in the history of American popular music, specifically in minstrel shows. Minstrelsy, popular in the 18th and 19th centuries, involved white performers in blackface makeup exaggerating racial stereotypes of African Americans, particularly enslaved people. These shows often featured recurring characters, including “Jim Crow” and “Zip Coon”.

“Zip Coon” and the Minstrel Tradition

“Zip Coon” was a stock character representing a Black dandy, often portrayed as foolish and attempting to imitate white upper-class society. A popular minstrel song associated with this character was “Ole Zip Coon,” which contained a chorus with striking similarities to the Disney song:

O Zip a duden duden duden zip a duden day. O Zip a duden duden duden duden duden day. O Zip a duden duden duden zip a duden day. Zip a duden duden duden zip a duden day.

This “Ole Zip Coon” tune was even sung to the melody of “Turkey in the Straw,” revealing its minstrel show origins.

Echoes in “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah”

While the exact connection is debated, the resemblance between “Ole Zip Coon” and “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” both in the “Zip” sound and the rhythm, is undeniable. It raises questions about whether the Disney songwriters were consciously or unconsciously drawing from this minstrel tradition. Regardless of direct intent, the historical echo is present, adding another layer to the song’s complicated backstory.

The Bluebird of Happiness: A Universal Symbol

Interestingly, the lyrics of “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” also reference a “bluebird on my shoulder,” a symbol of happiness found across various cultures. The bluebird as a harbinger of joy dates back to ancient China and appears in Native American and Russian folklore. In modern times, the symbol gained prominence through Maurice Maeterlinck’s symbolist play The Blue Bird. Program notes from a 1912 London performance describe the bluebird as “an ancient symbol in the folk-lore of Lorraine, and stands for happiness.” Maeterlinck’s play, like The Wizard of Oz, tells a story where the protagonists search for happiness only to realize it was with them all along, a theme resonating with the optimistic tone of “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah.”

Conclusion: Appreciating the Song with Context

“Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” is more than just a catchy, feel-good song. Its history encompasses an Oscar win, a controversial film, and surprising origins in minstrelsy. While the song itself has, for many, become detached from its problematic roots and is enjoyed for its simple message of happiness, understanding its full context provides a richer, and perhaps more nuanced, appreciation. By acknowledging this complex background, we can engage with “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” in a more informed and thoughtful way.