Once upon a time, in the era of jukebox rentals and weekend-long music fests at home, a particular song held an unusual power for a young listener. That song was “Seasons in the Sun,” by Terry Jacks. More than just a catchy tune, this song, sung from the perspective of a man on the verge of death, became an unexpectedly profound experience. While upbeat tracks like “Band on the Run” and “Waterloo” were fun for a spin or two, “Seasons In The Sun Song” demanded repeated listens, a full immersion into its melancholic soundscape via the family jukebox’s massive speaker. And invariably, it brought tears.

This wasn’t just teenage angst; it was something deeper. Crying to “Seasons in the Sun” was a strangely joyful act, as fulfilling as dancing in socks across a polished wooden floor to Wings or ABBA. Growing up in a stoic environment where emotions were muted, this song unlocked a powerful feeling, something exciting and worth revisiting. Yearly, for three days, a child would sincerely mourn a fictional stranger, lamenting the loss of nonexistent loved ones. It wasn’t perceived as odd then, just the impact of a truly compelling song.

Except, “Seasons in the Sun” isn’t objectively a “good” song in a critical sense. Yet, Terry Jacks sold millions of copies, resonating far beyond a niche audience. There must be a reason why this particular version of “Seasons in the Sun song” struck such a chord, especially considering it was a remake. Numerous artists had recorded similar versions in the decade prior, all commercially unsuccessful. The magic ingredient wasn’t Terry Jacks’ vocal delivery, which, while distinctive, is remarkably unemotional for a dying man. Nor was it solely the music, though the bassline is indeed hypnotic and the intro’s “sproings” are rumored to be courtesy of guitar legend Link Wray.

Terry Jacks’ genius with “Seasons in the Sun song” lies in subtraction, not addition. The journey of this song to global success is a story of stripping away sophistication from a sardonic Jacques Brel ballad, revealing a raw, intensely emotional core. While the result might be considered saccharine by some, it was a courageous act, one that allowed millions to confront the existential dread most people actively avoid. This exploration of “seasons in the sun song” delves into its surprising history and the elements that made Terry Jacks’ rendition a phenomenon.

The history of “Seasons in the Sun song” extends back to the 1960s, long before Terry Jacks’ 1974 hit. The realization that earlier versions existed came much later, in the mid-80s, with the discovery of a used Rod McKuen LP from 1964 titled “Seasons in the Sun.”

Rod McKuen LP Cover

Rod McKuen LP Cover

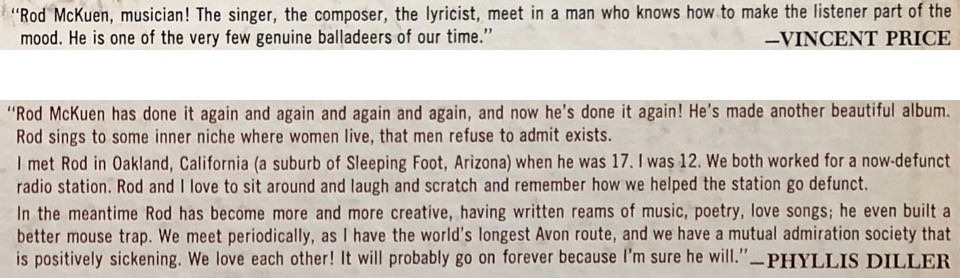

Rod McKuen was known as a commercially successful poet with titles like Listen to the Warm, but his singing career was less known. The LP back cover, featuring endorsements from Vincent Price and Phyllis Diller, offered a humorous assurance of its musical merit.

Quotes from Vincent Price and Phyllis Diller on Rod McKuen LP

Quotes from Vincent Price and Phyllis Diller on Rod McKuen LP

Rod McKuen LP Back Cover

Rod McKuen LP Back Cover

The liner notes revealed McKuen’s role in translating “Seasons in the Sun” from Jacques Brel’s “Le Moribond,” meaning “The Dying Man.” McKuen claimed to have aimed for a close translation, acknowledging the challenge of adapting French sensibilities to American tastes, where certain themes might be deemed too “rough” or sentimental. To truly understand the evolution of “seasons in the sun song,” it’s crucial to begin with Brel’s original French version.

Jacques Brel’s “Le Moribond” presents a starkly different tone than Terry Jacks’ hit. The French lyrics, while not perfectly captured by all English subtitles, reveal a cynical detachment. The dying man bids farewell to four individuals, entrusting them with the care of his wife. First, Emile, his best friend and partner in revelry; then, the priest, respected despite differing beliefs; third, Antoine, his wife’s lover, viewed with more disdain for his dullness than for the affair itself; and finally, his unfaithful wife. He loves her, but accepts his fate, acknowledging his own blindness to their relationship.

The chorus, repeated after each goodbye, is not mournful but a wish for celebration: he wants laughter, dancing, and revelry at his burial. This original “seasons in the sun song” is distinctly French in its sensibility. While Terry Jacks later claimed Brel wrote it in a Tangiers brothel (a dubious claim), the overall mood is far from maudlin. It’s cynical, detached. Death is universal; the singer is simply departing prematurely. His farewells, particularly to the priest and Antoine, are blunt, lacking conventional politeness, yet remain dignified and reasonable.

It’s difficult to pinpoint what McKuen considered “rough” for 1963 American audiences, as his translation not only retains the adultery but elevates it to the song’s central conflict. Initially, McKuen’s liner notes suggested a close adherence to Brel, with deviations only for perceived sensitivities. However, McKuen’s version of “seasons in the sun song” isn’t a direct translation. He repurposed the melody and the dying man concept, crafting a new narrative with a twist. Antoine disappears, Emile becomes both friend and betrayer, the priest transforms into a father figure, and the wife, Francoise, receives a name and a posthumous threat: the singer will haunt her for her infidelity with his friend.

Lyrically, McKuen retains only “adieu,” Emile’s name, wine, song, and the difficulty of dying in spring. But where Brel’s spring sentiment was a prelude to acceptance (“I’m going to the flowers with peace in my heart”), McKuen amplifies the pathos, making “die” the rhyme and spring, with its singing birds, the contrasting element. The most significant change is in the chorus. Brel’s future-oriented wish for a lively funeral is replaced with nostalgic recollections of shared past joys: “we had joy, we had fun, we had seasons in the sun.” McKuen shifts the focus to loss, dwelling on the past rather than the future.

While significantly altered, McKuen’s “seasons in the sun song” retains a cynical edge with the third verse’s twist. Initial loving farewells to his friend and father transform into a bitter curse for his wife. “Think of me” evolves into a veiled threat: “just be careful.” Brel’s narrator critiques his own naivete more than his wife’s betrayal, but both versions engage with death’s allure and fear without truly delving into its meaning. Death remains a given.

Before Terry Jacks, at least three other artists attempted McKuen’s version of “seasons in the sun song,” without substantial alterations to arrangement or lyrics. The Kingston Trio, who had connections with McKuen, released it as a single in 1964, mirroring McKuen’s arrangement but emphasizing the chorus harmonies. They, too, perpetuate the haunting of Francoise.

Four years later, British harmony group, The Fortunes, released their version as a single and album title track in 1969. They also highlighted Francoise’s infidelity, even adding a “heh” to underscore the irony. Despite these attempts, none achieved significant commercial success. This is surprising, considering they utilized the same melody and emotionally charged chorus that Terry Jacks would later transform into a global phenomenon. What did Terry Jacks understand about “seasons in the sun song” that others missed?

Terry Jacks possessed a pop sensibility honed by his previous success with The Poppy Family, fronted by his then-wife Susan Pesklevits. Their hit “Which Way You Goin’ Billy,” composed by Jacks, reached number one in Canada and number two in the US. Jacks admired The Kingston Trio’s “seasons in the sun song” and believed in its potential, even persuading The Beach Boys to record a version in the early 70s. Carl Wilson sang the verses, Mike Love the choruses, and Al Jardine and Jacks provided harmonies. However, The Beach Boys’ rendition remained unfinished, deemed too cheesy by some members. Crucially, they retained McKuen’s third verse about infidelity.

Four attempts to popularize the English “seasons in the sun song” failed commercially, one even unreleased. The infidelity element in McKuen’s third verse acted as a “lead weight,” hindering the song’s ascent to its melodic potential. McKuen’s interpretation, with its adultery gag, felt worldly and cynical, preventing a deeper exploration of the existential themes the song hinted at.

Terry Jacks eventually recorded his own version of “seasons in the sun song,” the one etched in global memory, selling millions of copies. Jacks claimed to have rewritten the song after a friend’s death, focusing on themes of goodbye to friends, father, and girlfriend. He mistakenly attributed the father substitution to himself, when it was McKuen who made that change. He also inaccurately recalled taking his “rewritten” version to The Beach Boys, as they recorded McKuen’s lyrics.

Jacks’ pivotal change to “seasons in the sun song” came in eliminating Francoise’s infidelity. She becomes Michelle, and crucially, she is faithful. The cynical third verse vanishes, replaced by insipid lines: “You gave me love and helped me find the sun,” and “You would always come around and get my feet back on the ground.” These lyrics are vapid, yet they align perfectly with the saccharine “joy/fun/seasons/sun” chorus, creating a cohesive, if shallow, emotional landscape.

Terry Jacks took McKuen’s emotional manipulation a step further. Death in his “seasons in the sun song” no longer unveils hidden truths; it simply amplifies the tragedy of leaving behind loved ones and good times. No bitter lessons are learned, only pure, unadulterated remorse. This naive remorse proved commercially potent. Jacks’ version became a global phenomenon, overshadowing his previous work and defining his career. He achieved financial security but became somewhat of a musical punchline.

Even listeners who loved “seasons in the sun song” as children might later view it as a joke. Upon discovering McKuen’s version, the perceived “bowdlerization” by Jacks could be appalling. Cover bands might “restore” the cynical third verse, believing it to be the song’s true intention. However, perhaps the uncritical childhood appreciation for Jacks’ version was closer to the song’s core emotional power. As a child grappling with mortality, the idea of saying goodbye forever was indeed the “worst thing in the world.”

Brel and McKuen approached this terribleness but retreated, masking it with adult cynicism and wife-ridicule. Terry Jacks, by contrast, erased the cynicism, focusing on the positive impact of his loved ones, particularly Michelle, who “made life less dark.” He shifted the song’s focus to the joy of living and the underlying terror of dying. In this sense, Terry Jacks’ “Seasons in the Sun song” mirrors a less refined version of Edvard Munch’s “The Scream.”

Edvard Munch's The Scream painting

Edvard Munch's The Scream painting

“The Scream,” despite its pop culture ubiquity, retains its power to distill a suppressed existential dread. Its satirical repurposing as refrigerator magnets might be a societal attempt to further suppress this dread even after Munch’s primal scream.

The Scream refrigerator magnets

The Scream refrigerator magnets

Terry Jacks’ “seasons in the sun song” offers a melodic scream, wallowing in the unpleasant reality of nonexistence, yet finding a strange satisfaction in it. This willingness to wallow distinguishes Jacks’ version. It’s not manipulative; it’s an honest portrayal of the human condition, acknowledging that death offers no upside beyond the bittersweet thought of being missed. This is the core irony the song reveals. Terry Jacks, through his naive approach, stumbled upon a profound truth. No cleverness can diminish the terror of nonexistence. Jokes fall flat, and aloofness is unconvincing. Most people avoid this thought entirely.

But when a catchy melody combines with lyrics confronting this very terror, people pay attention. Millions, however briefly, connect with this raw emotion, and a significant number will invest in a permanent sonic reminder of this uncomfortable truth. Terry Jacks’ “Seasons in the Sun song,” in its unexpected depth, provides just that: a melodic confrontation with mortality.