Image credit: ajari – https://www.flickr.com/photos/ajari/2354169886/

Like many, my appreciation for Japanese culture, from its rich culinary traditions to its captivating music, deepens over time. It’s a journey of continuous discovery, peeling back layers of understanding. This growing appreciation extends to recognizing the nuances of Japanese representation in media, hoping for authentic portrayals that reflect the complexities of history. While Japanese culture enjoys considerable visibility, one iconic song, “Ue o Muite Arukō,” globally recognized as “Sukiyaki,” remains shrouded in misunderstanding.

Kyu Sakamoto’s rendition of “Ue o Muite Arukō,” penned by Rokusuke Ei and Hachidai Nakamura, resonated instantly in Japan before captivating audiences across Europe and North America. However, the contexts surrounding its ascent to the top of global charts were markedly different, masking the song’s true essence.

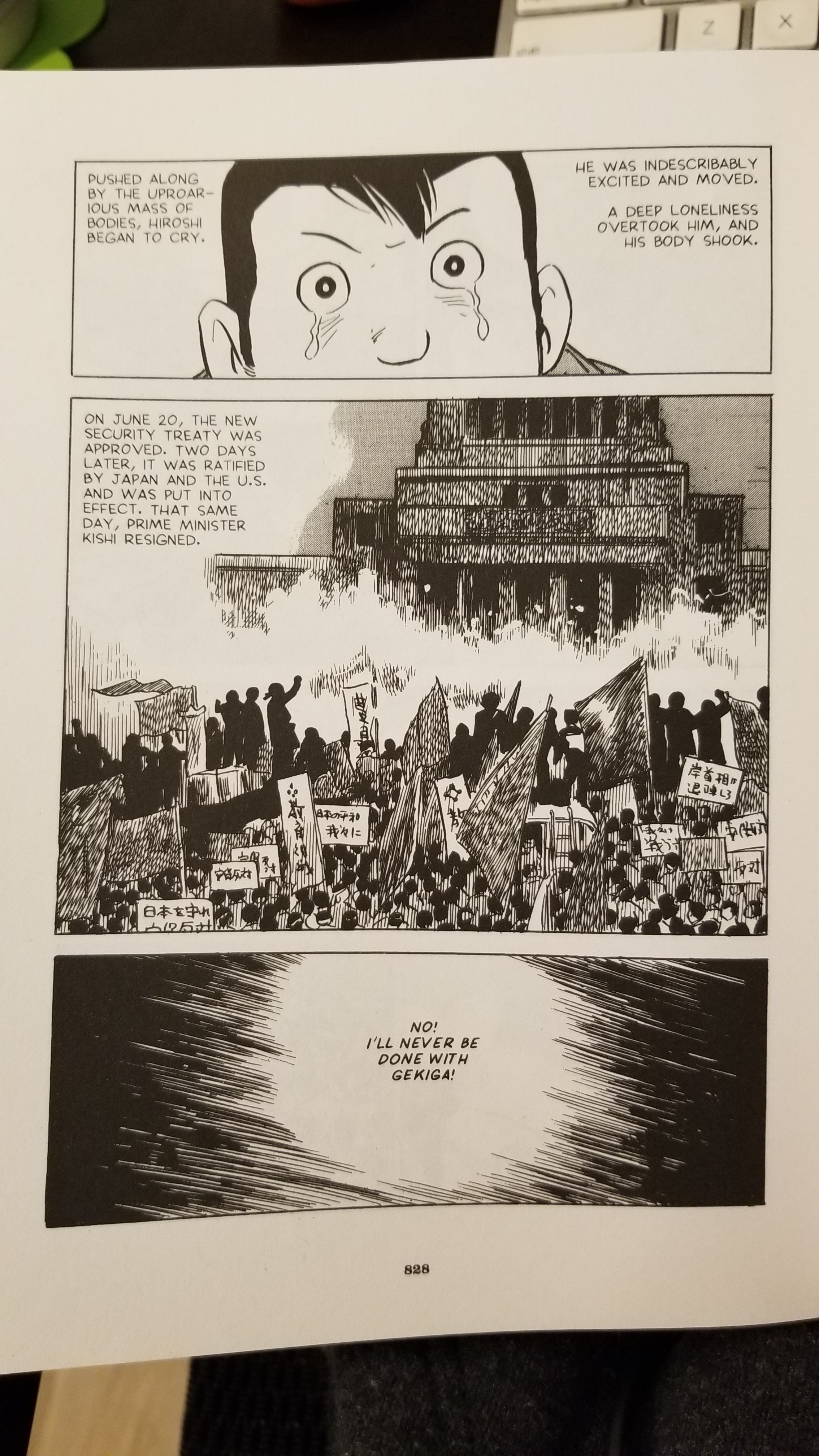

In 1960s Japan, the ratification of the U.S.-Japan Security Treaty ignited widespread public dissent. This treaty, aimed at solidifying the post-war alliance, was perceived by many Japanese citizens as an unwelcome extension of American military presence. The resulting Anpo protests became a massive outpouring of national sentiment. It was in the aftermath of these protests that Ei, witnessing the potential disillusionment of young activists facing governmental intransigence, composed the song.

The lyrics, especially when divorced from Sakamoto’s upbeat delivery, reveal a poignant melancholy. He sings with a smile, yet the underlying sentiment is one of sorrow and resilience in the face of disappointment.

Consider the translation, highlighting the emotional core of “Sukiyaki”:

| Japanese | English |

|---|---|

| Ue o muite arukouNamida ga koborenai you niOmoidasu haru no hiHitoribotchi no yoruUe o muite arukouNijinda hoshi o kazoeteOmoidasu natsu no hiHitoribotchi no yoru Shiawase wa kumo no ue niShiawase wa sora no ue ni Ue o muite arukouNamida ga koborenai you niNakinagara arukuHitoribotchi no yoru [Whistling] Omoidasu aki no hiHitoribotchi no yoru Kanashimi wa hoshi no kage niKanashimi wa tsuki no kage ni Ue o muite arukouNamida ga koborenai you niNakinagara arukuHitoribochi no yoruHitoribochi no yoru | I look up as I walkSo the tear won’t fallRemembering those spring daysBut I am all alone tonightI look up as I walkCounting the stars with tearful eyesRemembering those summer daysBut I am all alone tonight Happiness lies up above the cloudsHappiness lies up in the sky I look up as I walkSo that the tears won’t fallThough the tears well up as I walkFor tonight I am all alone [Whistling] Remembering those autumn daysBut I am all alone tonight Sadness lies in the shadow of the starsSadness lurks in the shadow of the moon I look up as I walkSo that the tears won’t fallThough the tears well up as I walkBut I am all alone tonight.But I am all alone tonight. |

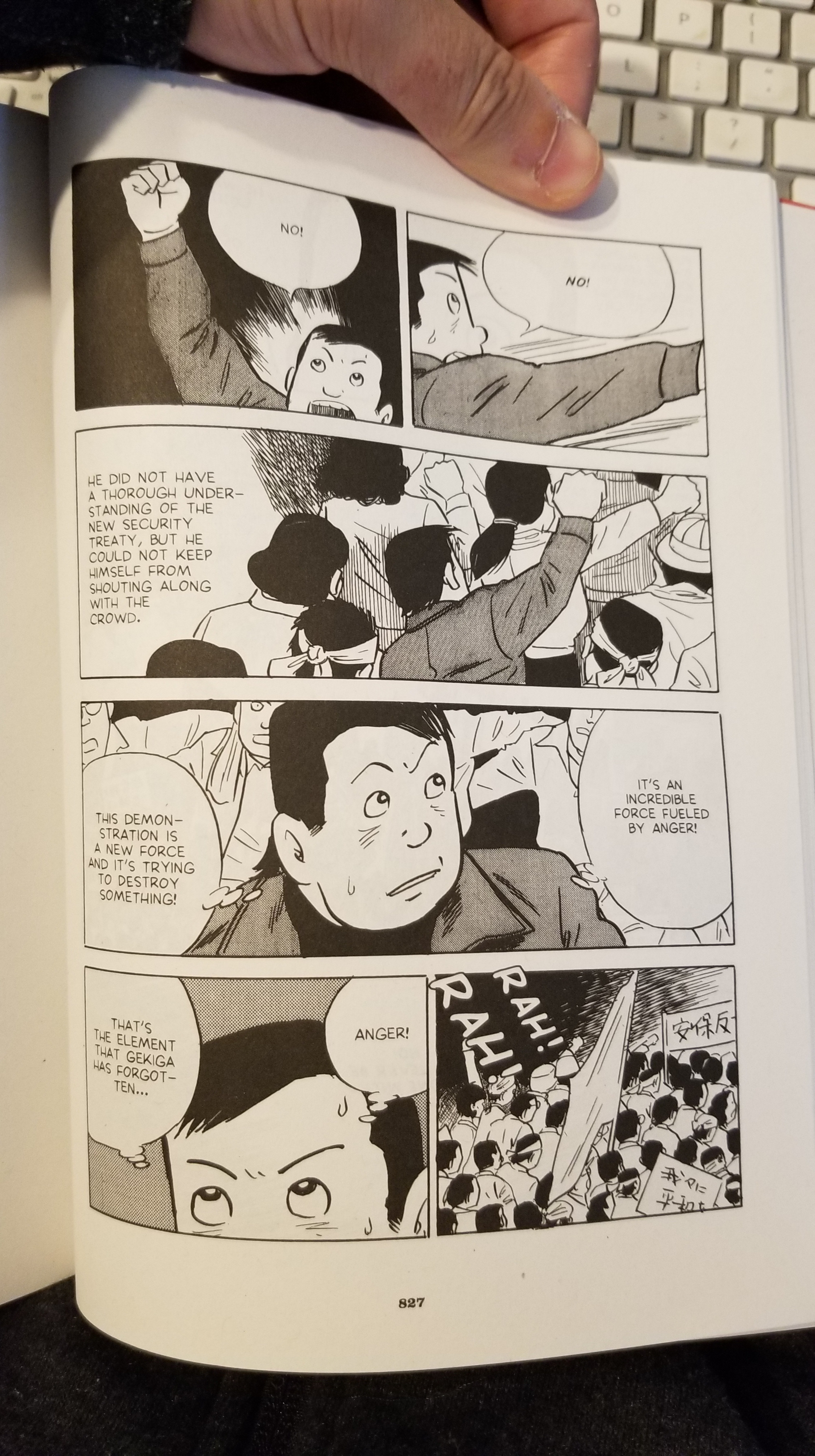

Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s graphic novel, “A Drifting Life,” vividly captures the Anpo protest atmosphere. In one scene, Tatsumi finds himself amidst the throng of demonstrators.

Amidst this “ocean of people,” as Tatsumi describes it, he reflects on his artistic journey, specifically his gekiga style, which aimed to inject greater emotional depth into manga. Looking skyward, tears welling, he mirrors the sentiment of “Sukiyaki.” He’s profoundly affected by the collective action yet feels intensely isolated within it – a complex interplay of emotions mirrored in the song.

These nuanced emotions, I believe, are precisely what “Ue o Muite Arukō” seeks to express. It’s a song that subtly encapsulates both personal sorrow and collective disappointment, cleverly disguised as a ballad of lost love. While superficially interpretable as a lament for romance, at its core, “Ue o Muite Arukō” functions as a protest song, a fact often overlooked in its popular representations.

The Global Journey of “Sukiyaki” and its Misinterpretation

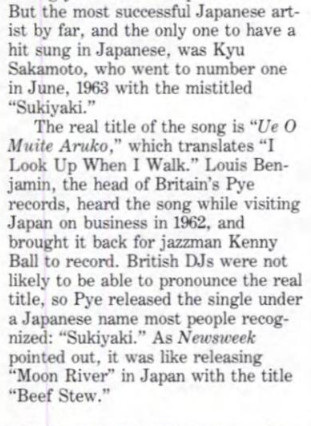

In 1962, Louis Benjamin of Pye Records in the UK rebranded “Ue o Muite Arukō” as “Sukiyaki” for its international release. The rationale was simple: “Sukiyaki” was deemed easier for English speakers to pronounce. This decision, while commercially successful, initiated a long-standing mischaracterization of the song.

The absurdity of renaming a song with such poignant lyrics after a popular Japanese hot-pot dish isn’t lost on anyone familiar with both. Imagine renaming a song like “Imagine” to “Pizza”—the disconnect is jarring. Fred Bronson’s “The Billboard Book of Number One Hits” recounts a Newsweek analogy, aptly comparing the name change to renaming “Moon River” to “Beef Stew” in Japan, highlighting the cultural dissonance.

Despite its nonsensical title in English, “Sukiyaki” achieved phenomenal success in the United States in 1963. This success, however, solidified the song’s detachment from its original meaning. Subsequent covers, such as A Taste of Honey’s 1980s rendition, further cemented this altered perception. These versions, often infused with lyrics about romantic longing, completely bypassed the song’s protest origins. In the 1980s, understanding of the Japanese language and culture outside of Japanese American communities was limited, contributing to this widespread misinterpretation. The haunting beauty of the original was largely replaced by conventional love song narratives.

“Sukiyaki” in Contemporary Popular Culture: Lost in Translation

More recently, the song appeared in the 2020 Netflix series “Dash & Lily.” In a heartwarming scene, Dash participates in making Daifuku Mochi with elderly Japanese women, with “Sukiyaki” playing softly in the background. The context, however, remains firmly within the realm of romance, soundtracking Dash’s reflections on his burgeoning relationship, not any sense of societal unease or historical reflection. Even with the commendable casting of Japanese American actors for Lily’s family (Lily herself was originally white in the book), the song’s usage reinforces its romantic, rather than protest, connotation.

Another notable instance is in “Mad Men.” Some interpretations suggest the song’s inclusion is a somber nod to Kyu Sakamoto’s tragic death in a plane crash, coinciding with a character’s father dying in a plane accident within the episode. However, it’s more likely that the song served as recognizable Japanese background music for a restaurant scene. The historical inaccuracy – the episode is set in 1962, before the song’s US breakthrough – further points to a superficial understanding of “Sukiyaki.” Adding to the problematic nature of the scene is the stereotypical portrayal of an Asian waitress, a pastiche of Asian fashion tropes, reinforcing outdated and reductive representations.

Perhaps the most crucial takeaway is to remember that “Sukiyaki The Song” is profoundly disconnected from sukiyaki the dish. It’s a song born from protest, encapsulating the melancholy and heartbreak of a generation witnessing political decisions clashing with their aspirations for their nation. Understanding this context enriches our appreciation of “Ue o Muite Arukō,” transforming it from a catchy tune into a poignant anthem of resilience and quiet defiance.