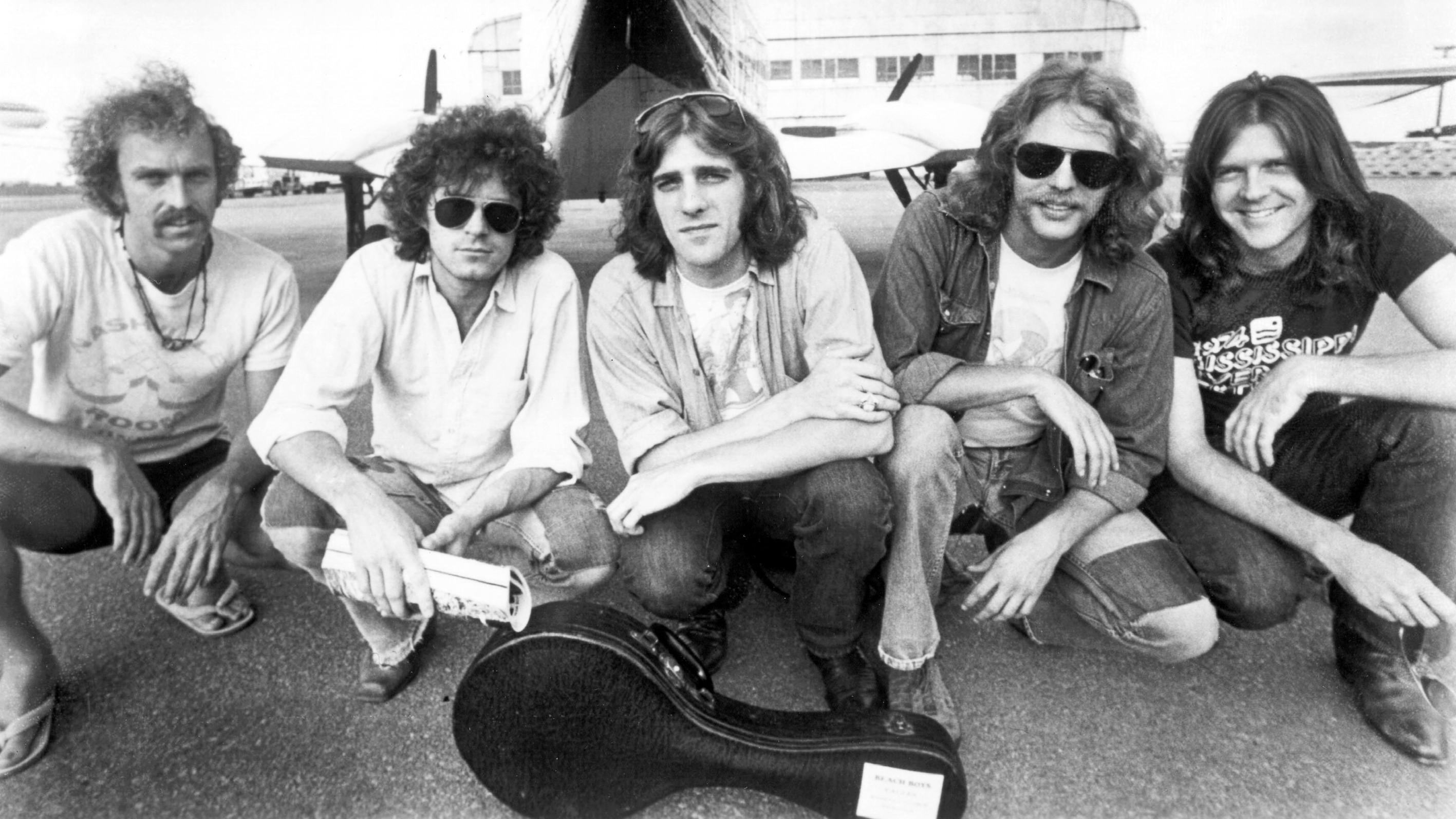

From their mellow beginnings to stadium rock icons, The Eagles have crafted a soundtrack for generations. Often labeled with the somewhat limiting “country rock” tag, their music transcends simple categorization. While known for their harmonies and laid-back vibes, a closer listen reveals a rich tapestry of rock & roll grit, soulful undertones, and nods to country, bluegrass, and even funk. As Don Henley himself stated, the band’s ambition was clear: “to write good, memorable songs, make albums that had little or no filler, that were consistent from beginning to end in terms of songwriting and production.”

This exploration delves into 40 of The Eagles’ most enduring songs, drawing upon insights from band members and collaborators like JD Souther and Bill Szymczyk. Discover the stories behind the music – the real-life inspirations, the romantic entanglements, and the studio magic that brought these tracks to life. These songs are more than just hits; they are a testament to the band’s lasting appeal and their commitment to musical excellence.

Hotel California (1976)

Eagles Hotel California song art

Eagles Hotel California song art

“Hotel California,” perhaps the Eagles’ most iconic track, is more than just a song; it’s a cultural touchstone. Don Henley described it as “our interpretation of the high life in Los Angeles,” born from the experiences of “middle-class kids from the Midwest” navigating the excesses of the West Coast. Beyond the glitz, the song paints a sweeping, almost cinematic portrait of the darker facets of the American Dream, hinting at themes of disillusionment and the seductive nature of fame and fortune.

The song’s genesis was humble, starting as a 4-track demo by guitarist Don Felder in his Malibu beach house. Henley and Glenn Frey then fleshed out the concept, with Frey’s lyrics conjuring “L.A.’s tarnished elegance” – a world imbued with both “mystery and possibility.” Originally considered as “Mexican Reggae,” the track evolved during recording sessions in Miami and Los Angeles. The legendary guitar duel between Felder and Joe Walsh, a three-day labor of sonic intensity, became the song’s dramatic climax. Released in December 1976, “Hotel California” dominated charts for 19 weeks, anchoring a monumental album and sparking countless interpretations, from satanism to drug addiction. Glenn Frey aptly described it as “just like a little movie,” where “a lot of it doesn’t have to make sense.”

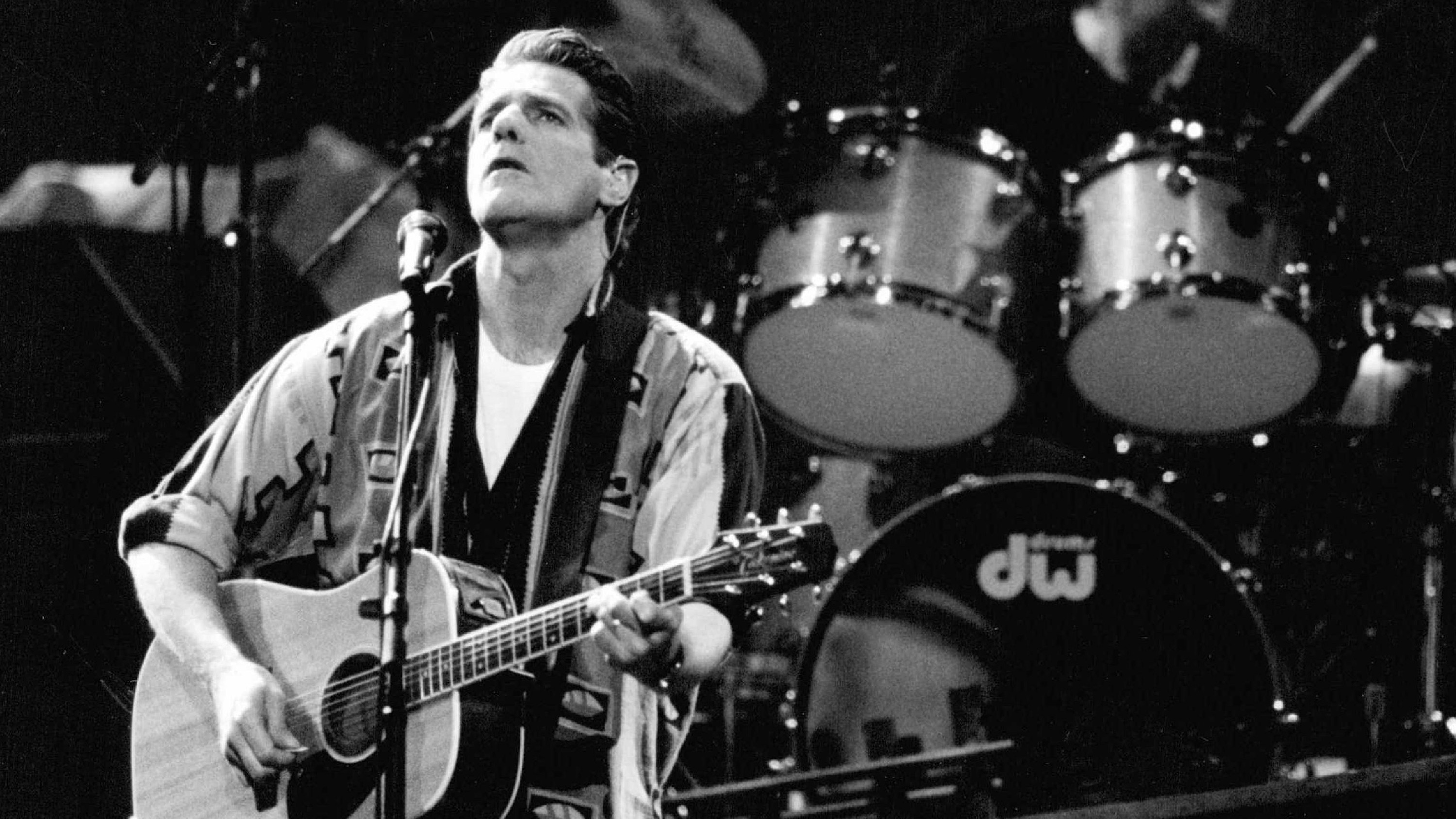

Take It Easy (1972)

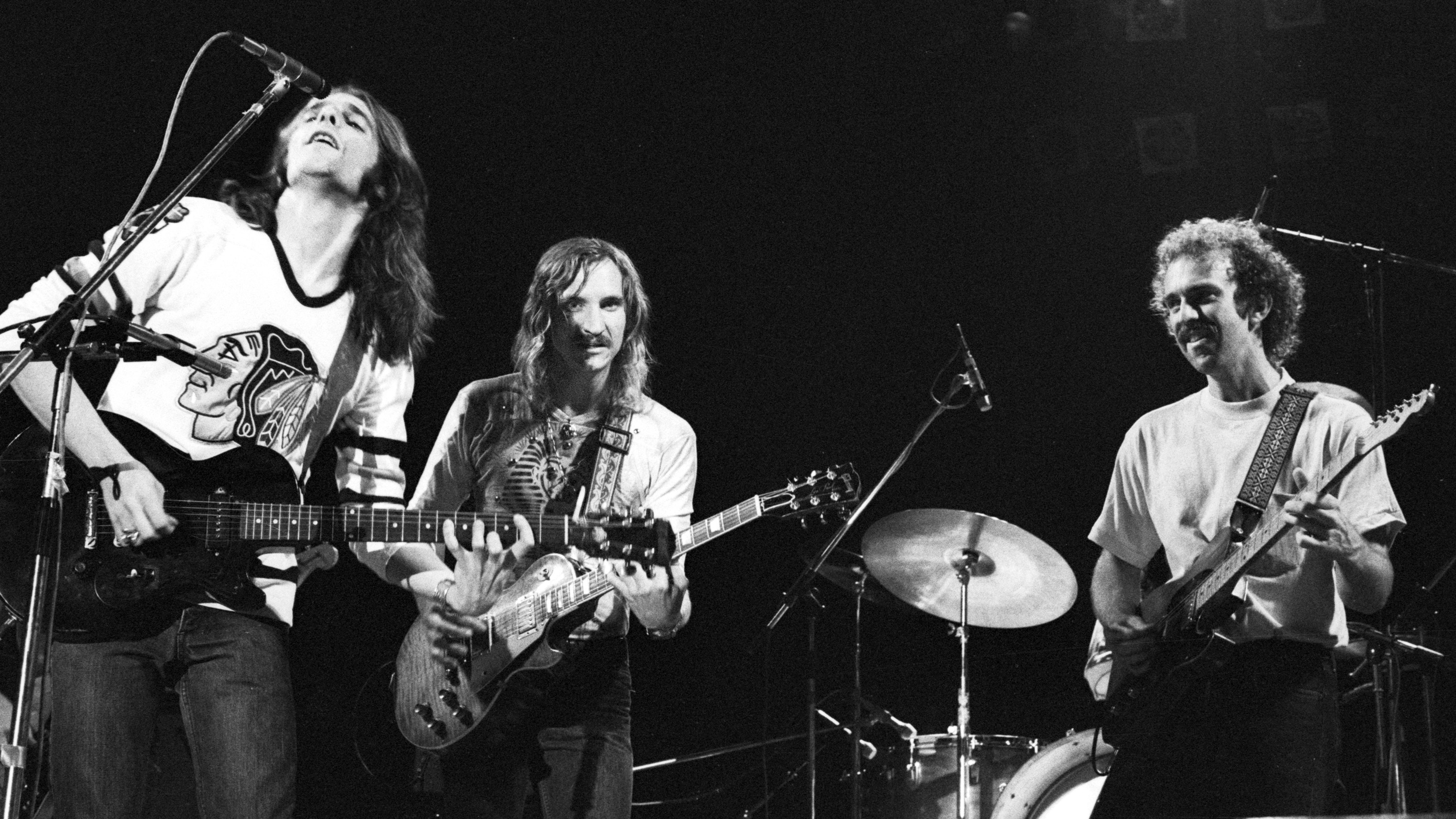

Eagles Take It Easy performance

Eagles Take It Easy performance

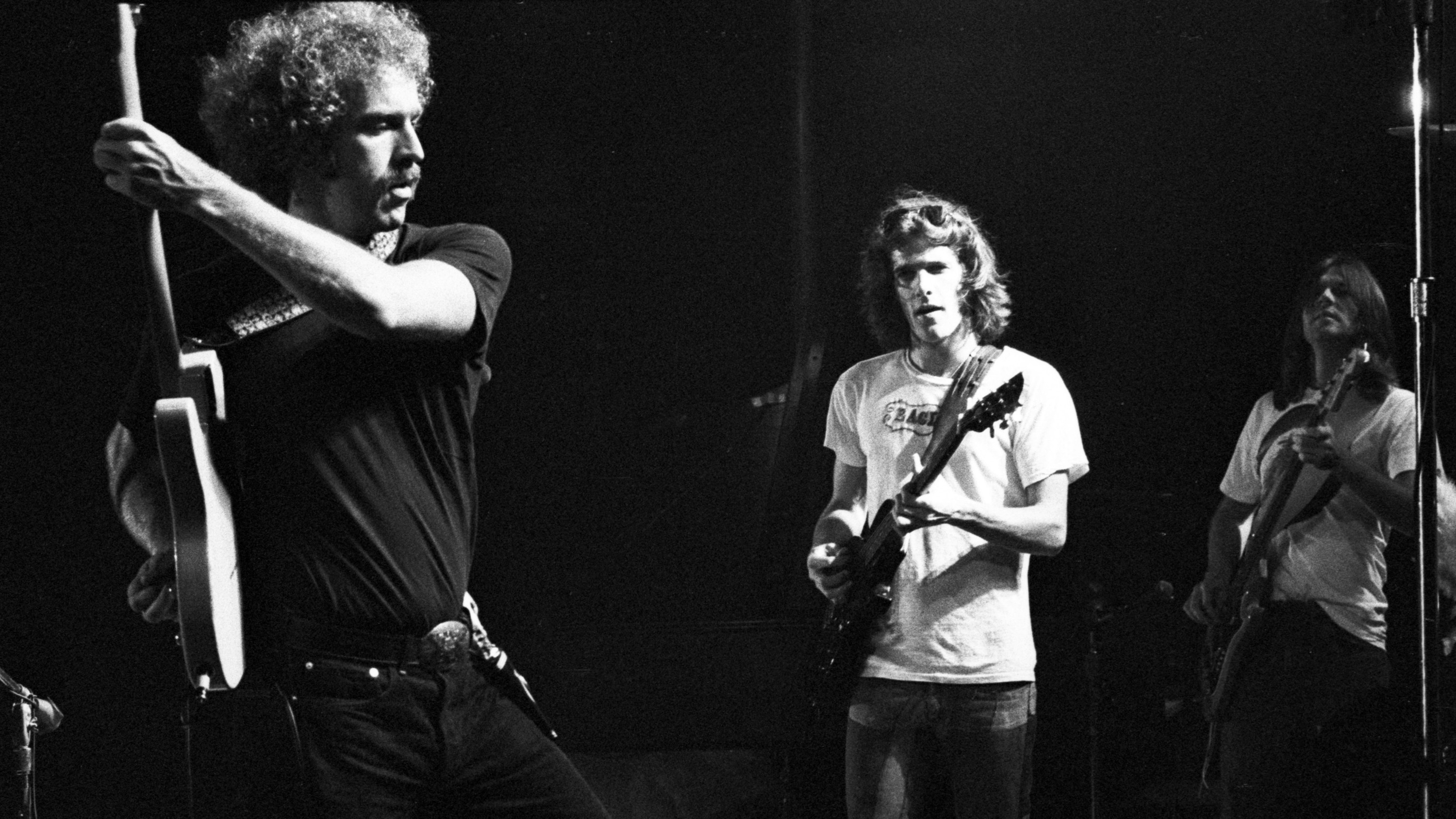

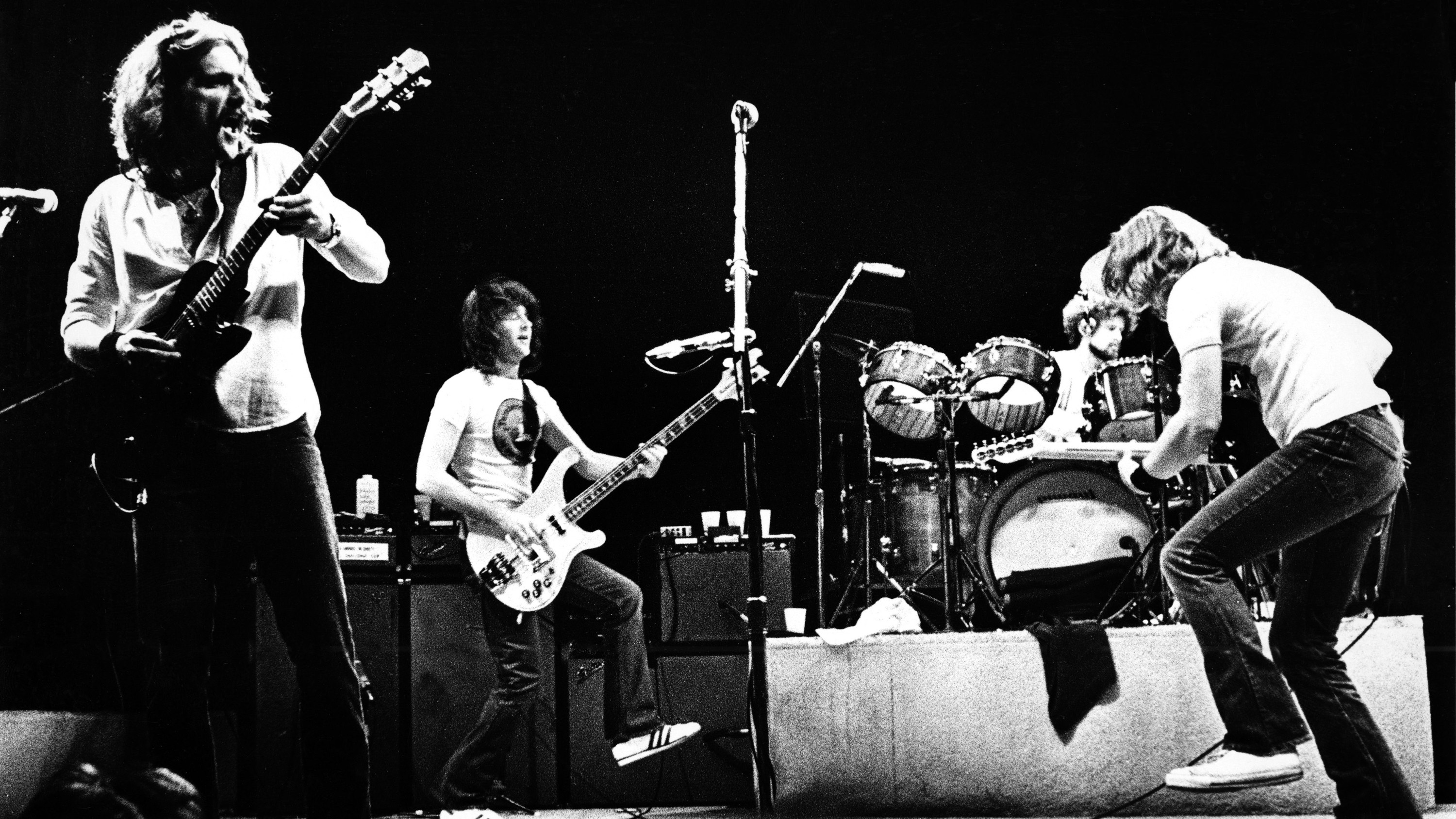

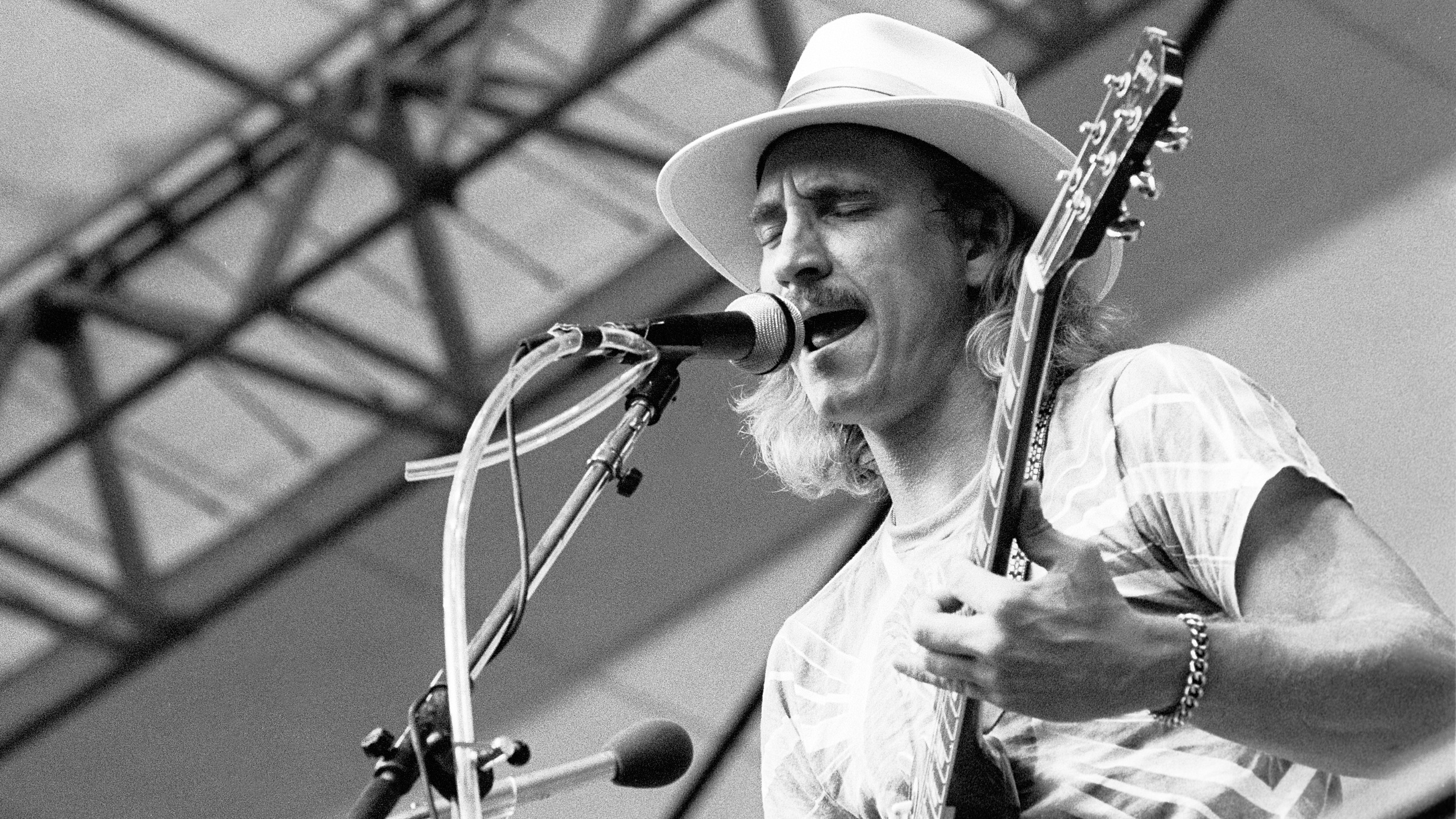

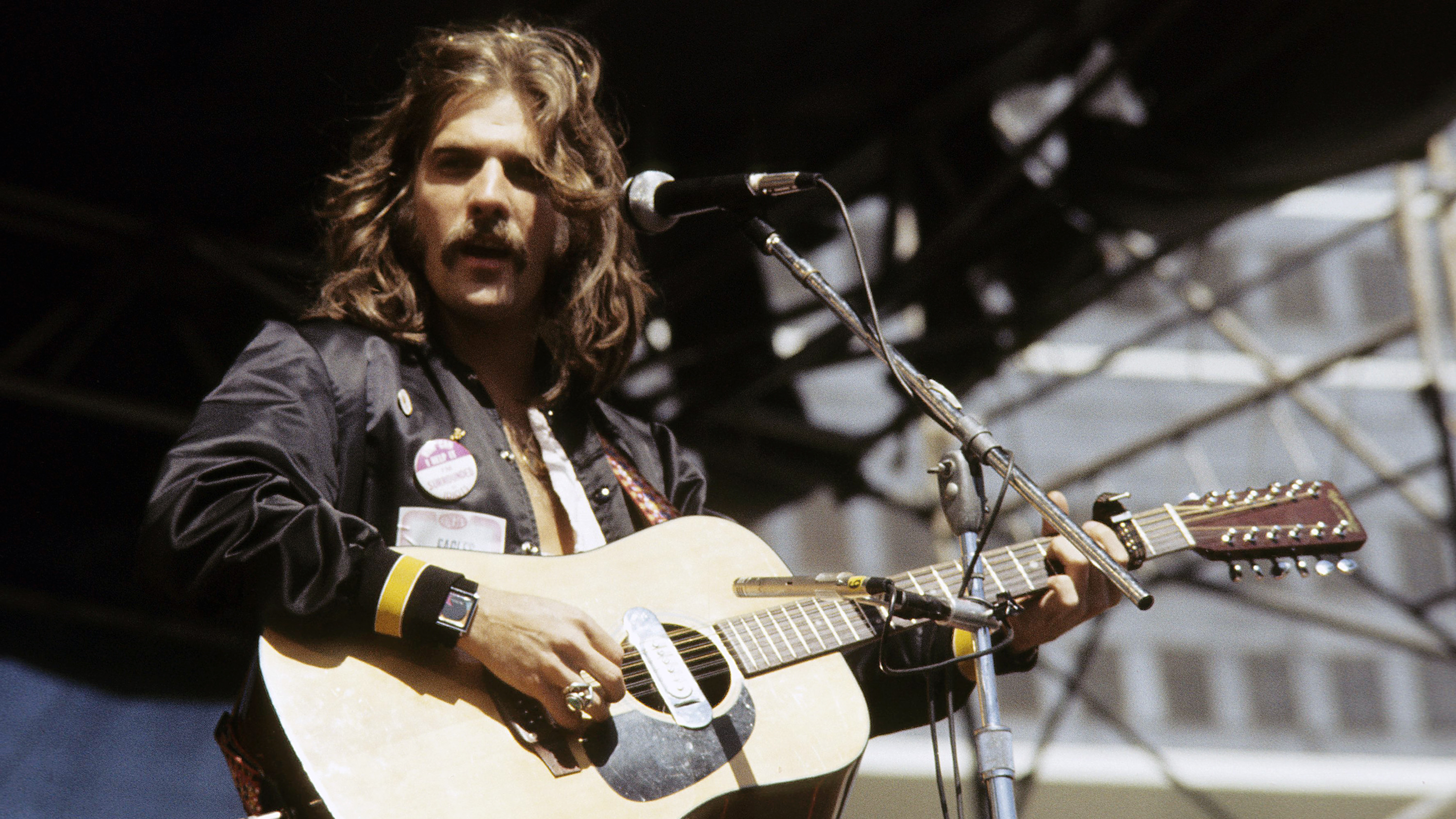

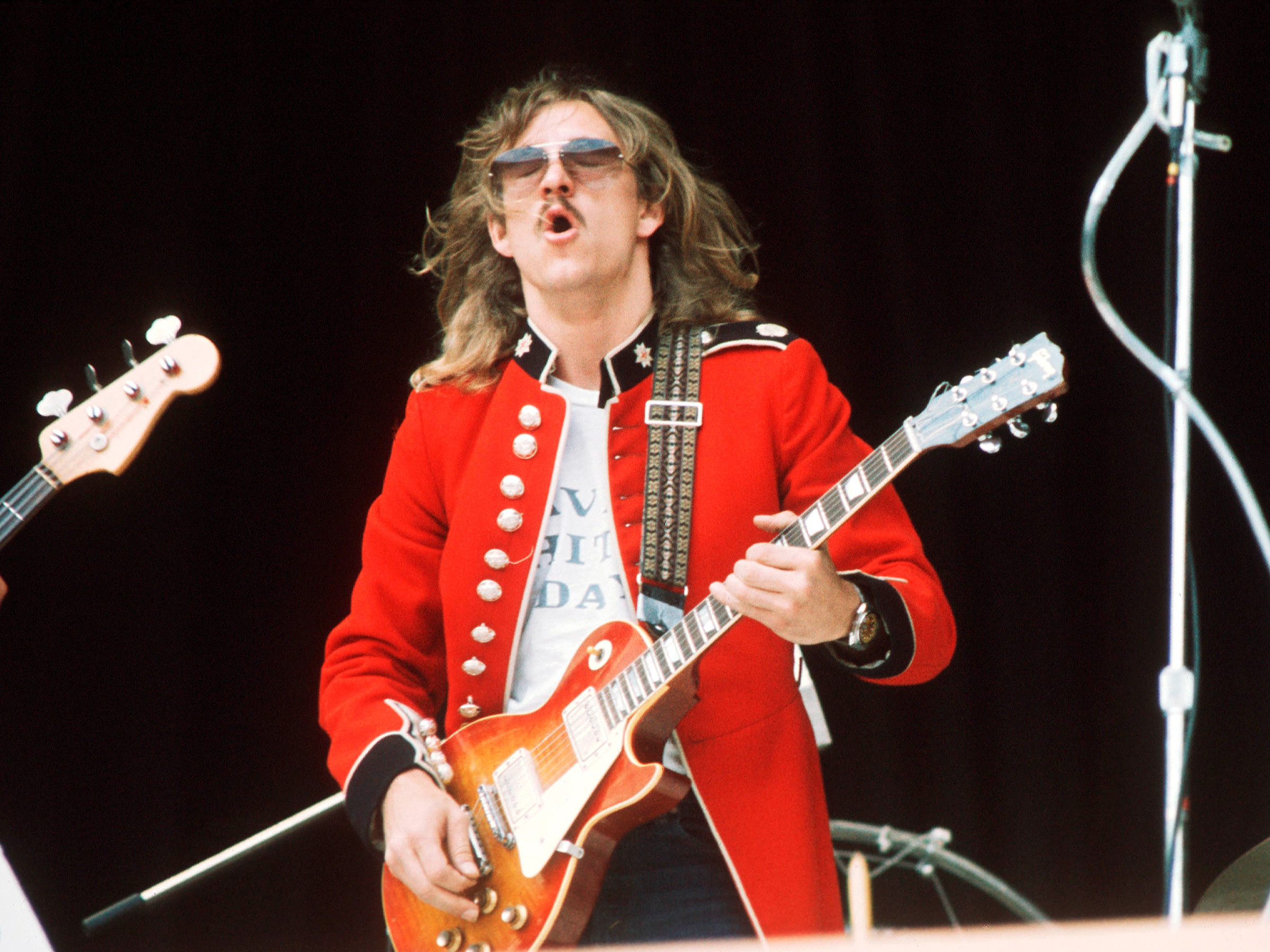

“Take It Easy” became the Eagles’ anthem, a song that embodies the carefree spirit of the open road and the band’s early, mellow vibe. Jackson Browne initiated the song during a road trip through Utah and Arizona, crafting a rough version that he then shared with his neighbor, Glenn Frey. Frey immediately recognized the song’s potential, famously contributing the line, “It’s a girl, my lord, in a flatbed Ford, slowin’ down to take a look at me,” building upon Browne’s existing verses about Winslow, Arizona.

Browne entrusted the song to Frey and the Eagles. Guitarist Bernie Leadon recalls the immediate connection the band felt: “The song has this momentum to it – it’s cruising.” From its breezy intro to its instantly memorable title phrase, “Take It Easy,” the Eagles’ debut Top 20 hit announced their arrival with a signature sound. “Just those open chords felt like an announcement, ‘And now…the Eagles,’” Frey reminisced. Timothy B. Schmit, then with Poco, remembers the song’s impact within the country-rock scene: “We would be driving along the road to some college gig, and then we would hear ‘Take It Easy’ on the radio and kind of sigh. This band was doing the same genre, and they were soaring past us.”

Desperado (1973)

Eagles Desperado album art

Eagles Desperado album art

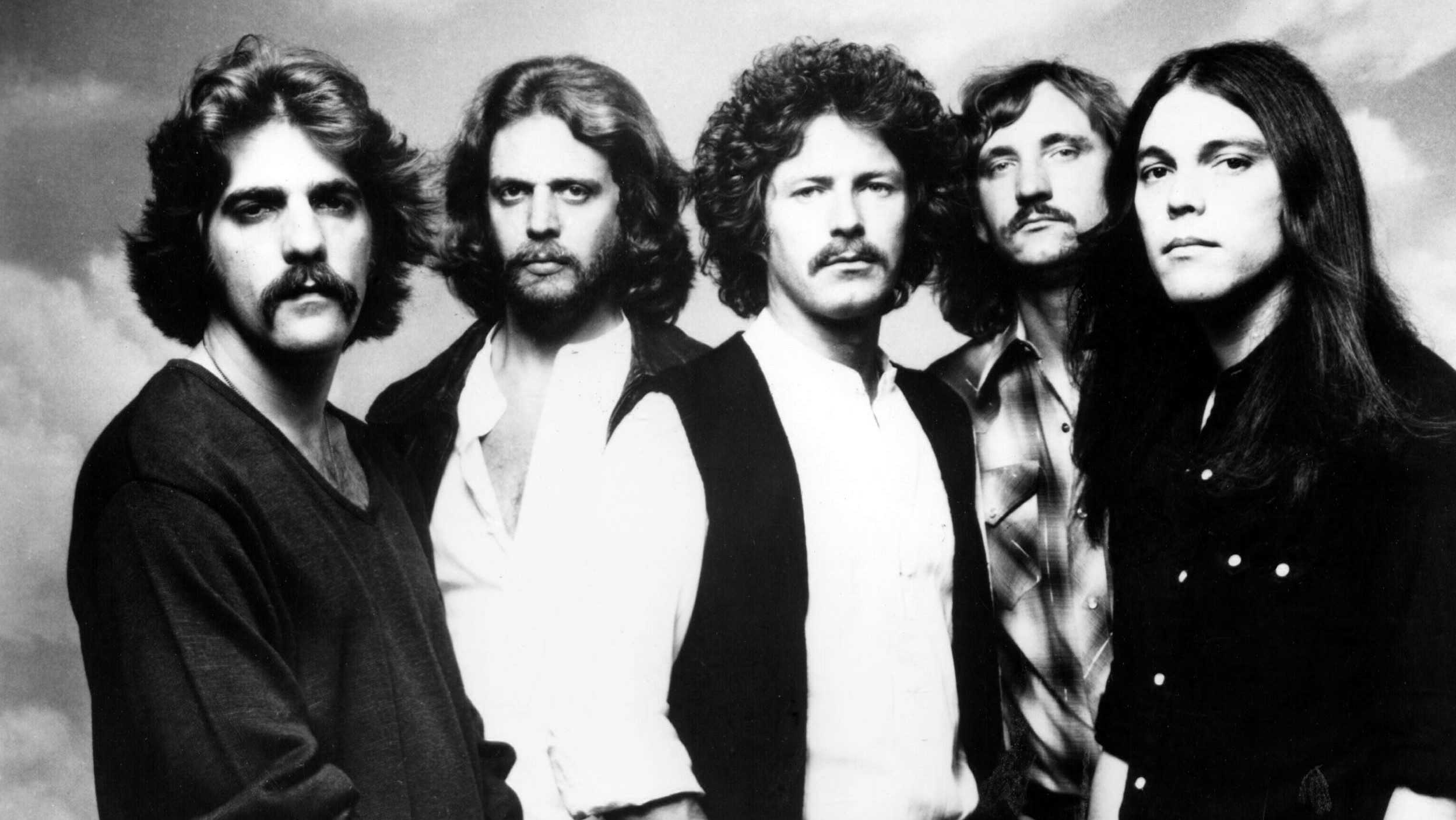

“Desperado,” the evocative title track from the Eagles’ second album, paints a vivid Western landscape, both musically and lyrically. Its cinematic orchestral arrangement and introspective lyrics explore themes of embracing one’s wild side and the yearning for connection. This song marked an early collaboration between Henley and Frey as songwriters, solidifying their creative partnership.

Shortly after recording their debut album, the duo convened at Henley’s Laurel Canyon home, gathered around an upright piano. Henley presented Frey with a melody and chord progression he’d been developing since 1968. Initially, the lyrics were directed at a friend named Leo and touched upon astrological themes, according to Henley. However, inspired by Jackson Browne’s suggestion, they shifted to a Western motif. The Eagles then recorded “Desperado” with the London Symphony Orchestra – an experience Henley described as “terrifying.” The result became a country-rock ballad of landmark status, covered by artists across genres, including Johnny Cash, Neil Diamond, and Miranda Lambert. Glenn Frey reflected on their songwriting dynamic: “I brought Don ideas and a lot of opinions, he brought me poetry. We were a good team.”

Peaceful Easy Feeling (1972)

Eagles Peaceful Easy Feeling live

Eagles Peaceful Easy Feeling live

“Peaceful Easy Feeling,” the third hit single from the Eagles’ debut album, marked their first collaboration with songwriter Jack Tempchin, who would later contribute to Frey’s solo career with “You Belong to the City.” Tempchin penned the ballad after a gig at a small coffee shop in El Centro, California. He recounted, “It was my first time in the desert, and the view of the stars was amazing. I was attracted to a waitress there, but unfortunately, she didn’t feel the same way about me because she went home – without me. I wound up sleeping on the floor in the club with my guitar instead of the girl. It was then that I started writing ‘Peaceful Easy Feeling.’”

Frey heard Tempchin play the song at Jackson Browne’s house and immediately asked to try it with the Eagles. Tempchin recalled his reaction to the Eagles’ rendition: “The next day, Glenn brought me a cassette of what they had done with it. It was so good I couldn’t believe it.” With its gentle strumming and signature three-part harmonies, “Peaceful Easy Feeling” felt like a natural extension of “Take It Easy.” Bernie Leadon described the song’s effortless feel: “You just fall in.”

New Kid in Town (1976)

Eagles New Kid in Town performance

Eagles New Kid in Town performance

During the early songwriting sessions for Hotel California, J.D. Souther shared a fragment of a song with the Eagles at Frey’s house. “Everyone looked at me: ‘Man, that’s a single, that’s a hit. Where’s that been?’” Souther remembered. “I didn’t know what else to do with it.” Frey then developed a narrative around Souther’s musical idea. Henley described the song as exploring “the fleeting, fickle nature of love and romance” and “the fleeting nature of fame, especially in the music business.”

The song’s themes resonated with the changing musical landscape of the time, as punk rock and other new genres began to challenge established acts like the Eagles. Souther acknowledged this shift: “We were approaching 30 and could see that the rearview mirror was full of newcomers as hungry as we had been.” (Souther clarifies that the song is not about Bruce Springsteen, contrary to some rumors). “New Kid in Town” featured Randy Meisner on a guitarrón, a Mexican acoustic bass, lending a south-of-the-border melancholic feel. Its intricate, overlapping harmonies earned the band a Grammy for Best Vocal Arrangement, solidifying its place among the Eagles’ most sophisticated and emotionally resonant songs.

Already Gone (1974)

Eagles Already Gone On the Border album art

Eagles Already Gone On the Border album art

“Already Gone,” penned by Jack Tempchin of “Peaceful Easy Feeling” fame, injected a harder rock edge into the Eagles’ sound. Following the moderate success of Desperado, the band sought more radio-friendly material and saw “Already Gone” as an opportunity to toughen their musical approach. The original version, co-written by Tempchin and Robb Strandlund, was softer than the Eagles’ final, more assertive rendition.

The band initially attempted the song during the early London sessions for On the Border, which were eventually abandoned. After switching producers from Glyn Johns and relocating to Los Angeles, they revisited “Already Gone” and captured its definitive version quickly. Tempchin recalled Frey’s call from the studio: “Hey, you know that country song you wrote? I think we could make that a great rock song.” Frey then played the Eagles’ recording over the phone. Adding to the song’s spontaneous energy, the band even kept an improvised moment at the end – Frey singing “all right, nighty night.” Frey later explained, “That’s me being happier, that’s me being free.” “Already Gone” became the opening track of On the Border, the Eagles’ first Number One album, signaling a shift towards a more rock-oriented sound that broadened their appeal.

Lyin’ Eyes (1975)

Eagles Lyin Eyes Barry Schultz photo

Eagles Lyin Eyes Barry Schultz photo

“Lyin’ Eyes,” a six-minute narrative song, emerged from a real-life observation by Glenn Frey. He reportedly saw an attractive young woman dining with an older man at an L.A. restaurant and remarked, “Look at those lyin’ eyes,” sparking the concept for the song. It tells the story of a woman trapped in a loveless marriage with a wealthy older man, who seeks emotional fulfillment “on the cheatin’ side of town” with her boyfriend.

Frey recalled the song’s effortless creation: “I don’t want to say it wrote itself, but once we started working on it, there were no sticking points.” Bernie Leadon emphasized Frey’s storytelling ability, evident in his vocal delivery on “Lyin’ Eyes”: “As the saying goes, Henley could sing the phone book and make it sound interesting, but Glenn was a great storyteller. Just listen to the way he sings ‘Lyin’ Eyes.’” Enhanced by Leadon’s guitar work and its Nashville-tinged feel, the song became one of the few Eagles singles to cross over to the country charts. Producer Bill Szymczyk highlighted the band’s meticulous studio approach, noting that the opening line alone – “City girls just seem to find out early” – required six takes to perfect, piecing together syllables and words from different recordings.

Life in the Fast Lane (1976)

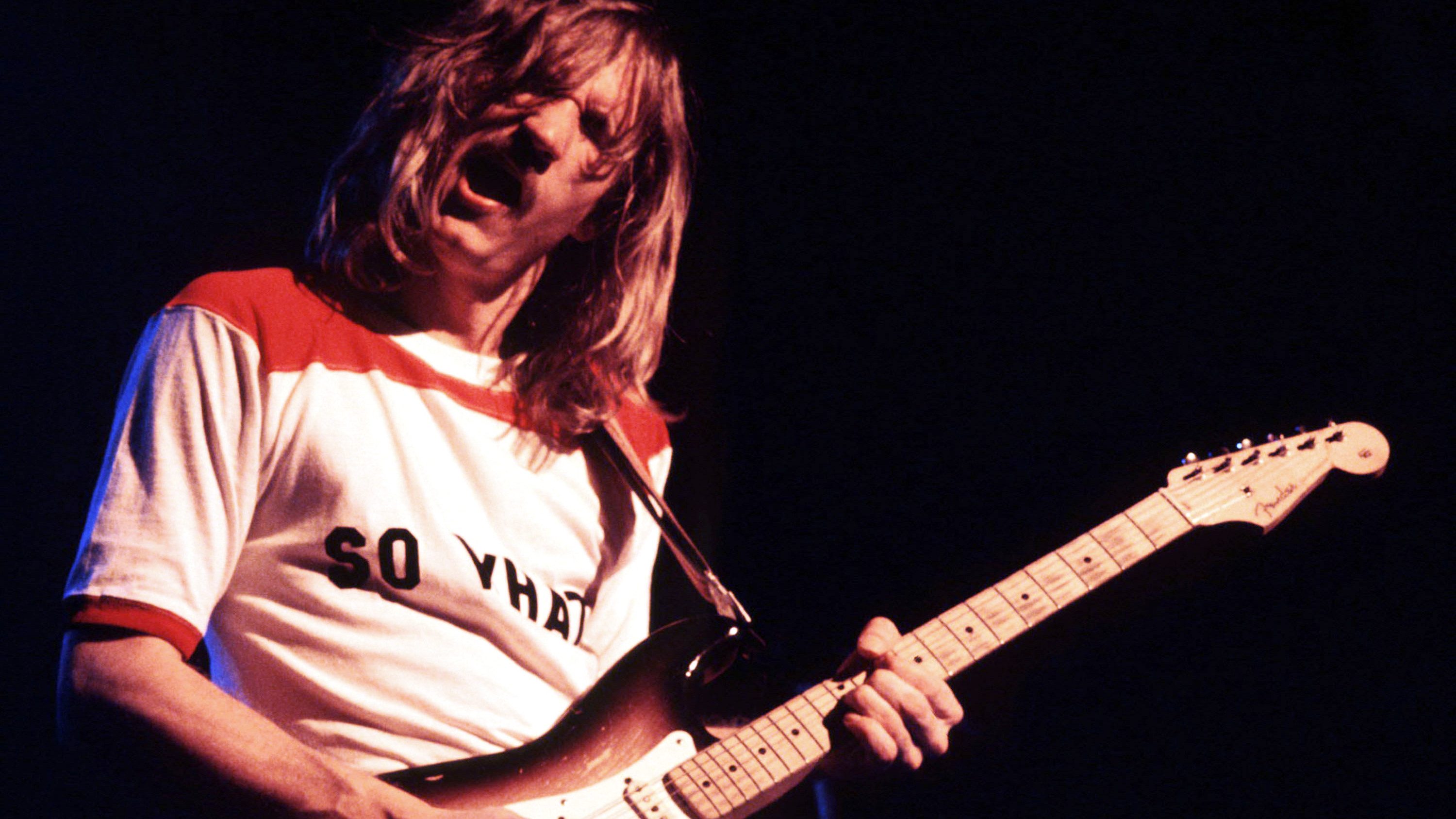

Eagles Life in the Fast Lane performance

Eagles Life in the Fast Lane performance

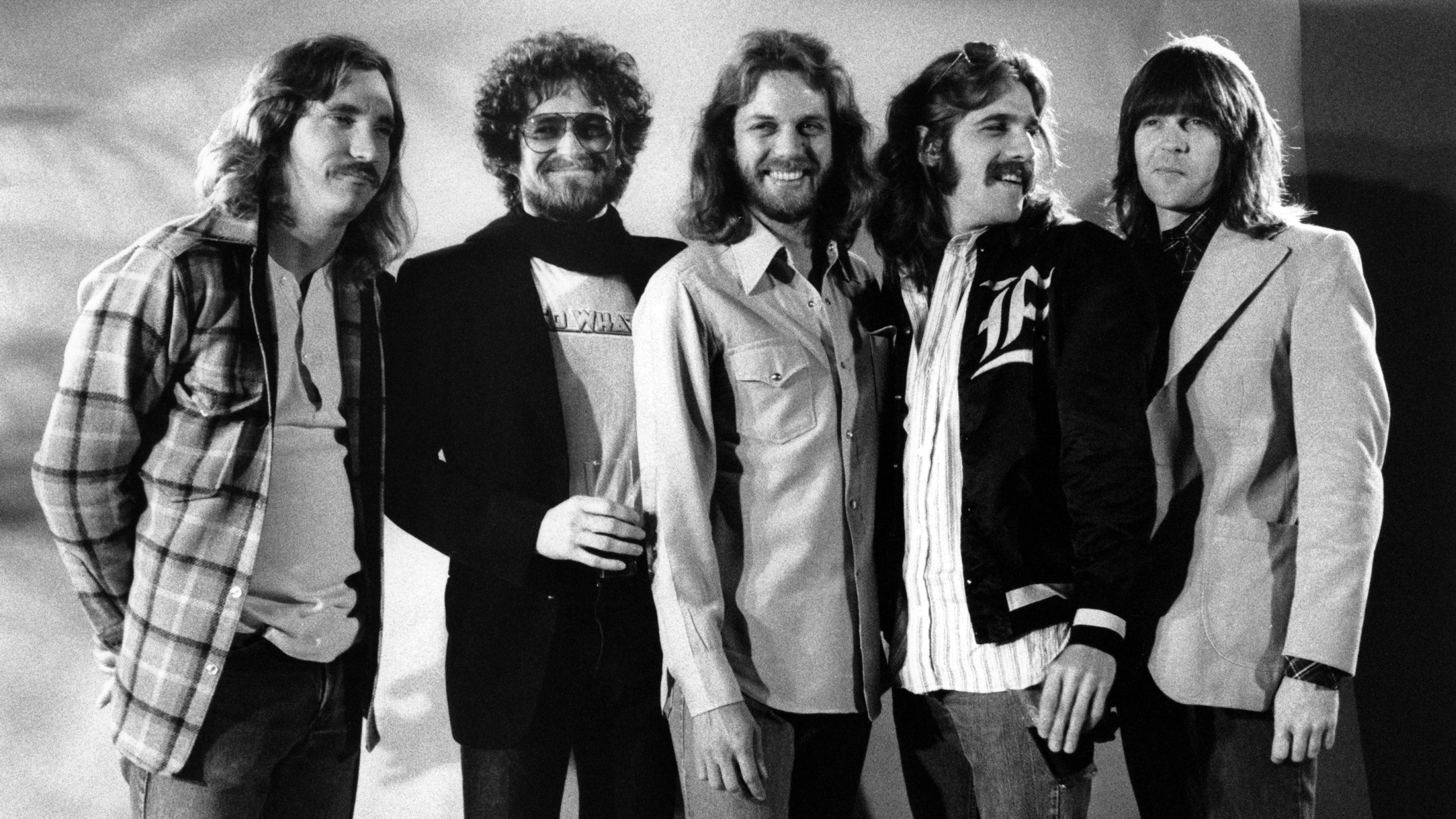

The title “Life in the Fast Lane” came to Glenn Frey during a car ride with a friend known as “the Count.” As they sped down the highway, exceeding 75 mph, Frey exclaimed, “Hey, man, slow down.” His friend’s response, “Hey, man, it’s life in the fast lane,” immediately struck Frey as a perfect song title.

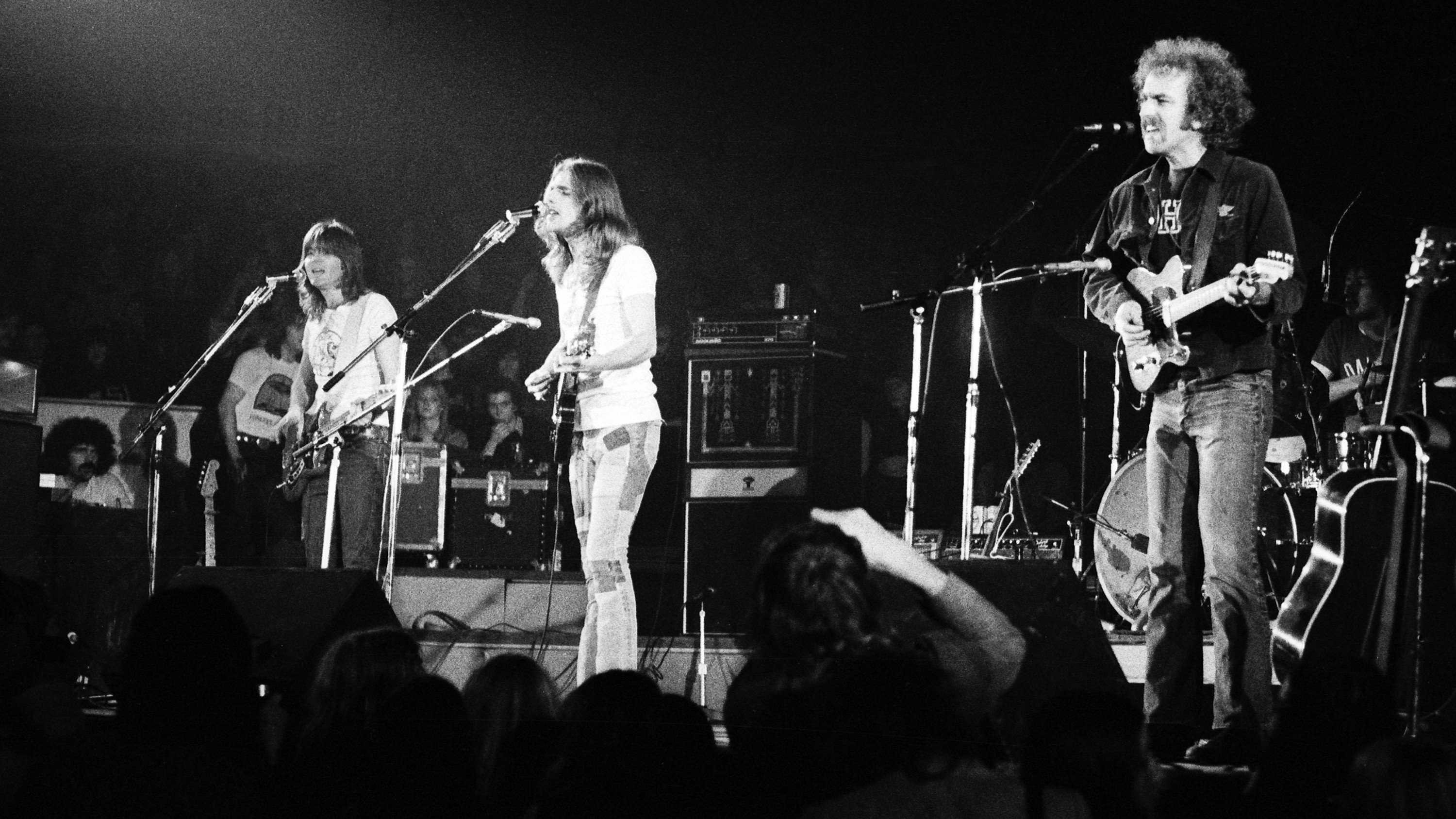

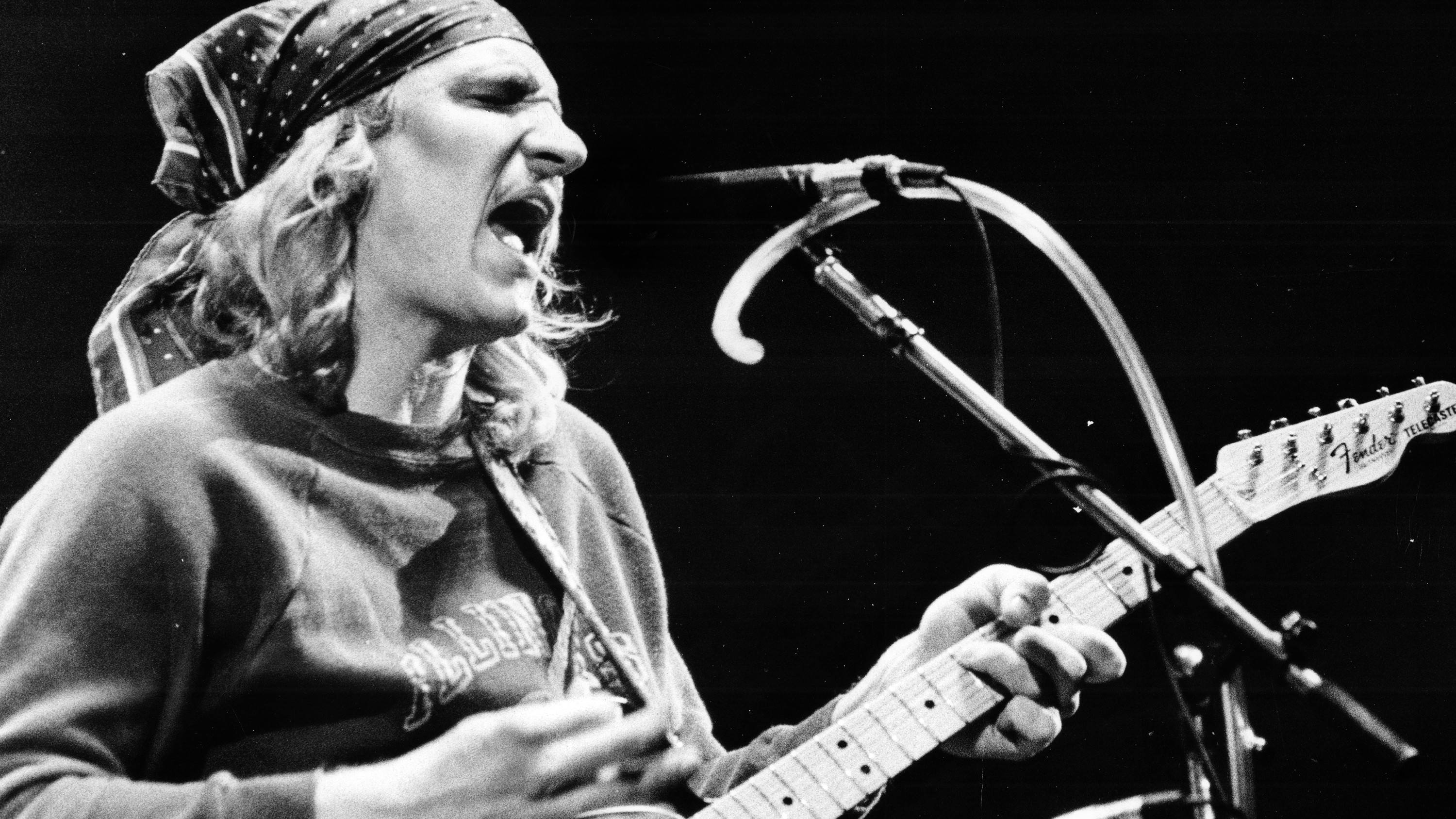

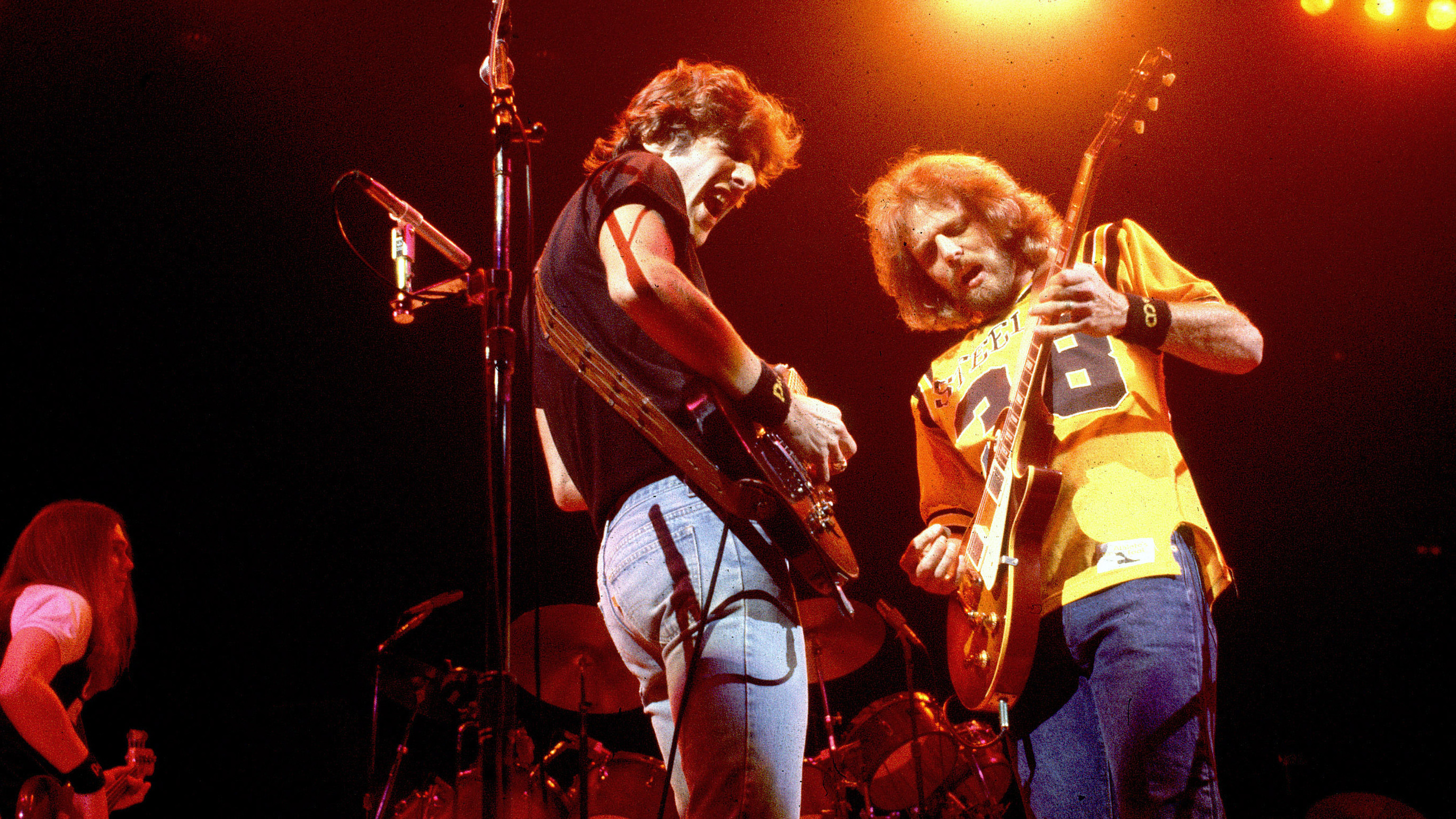

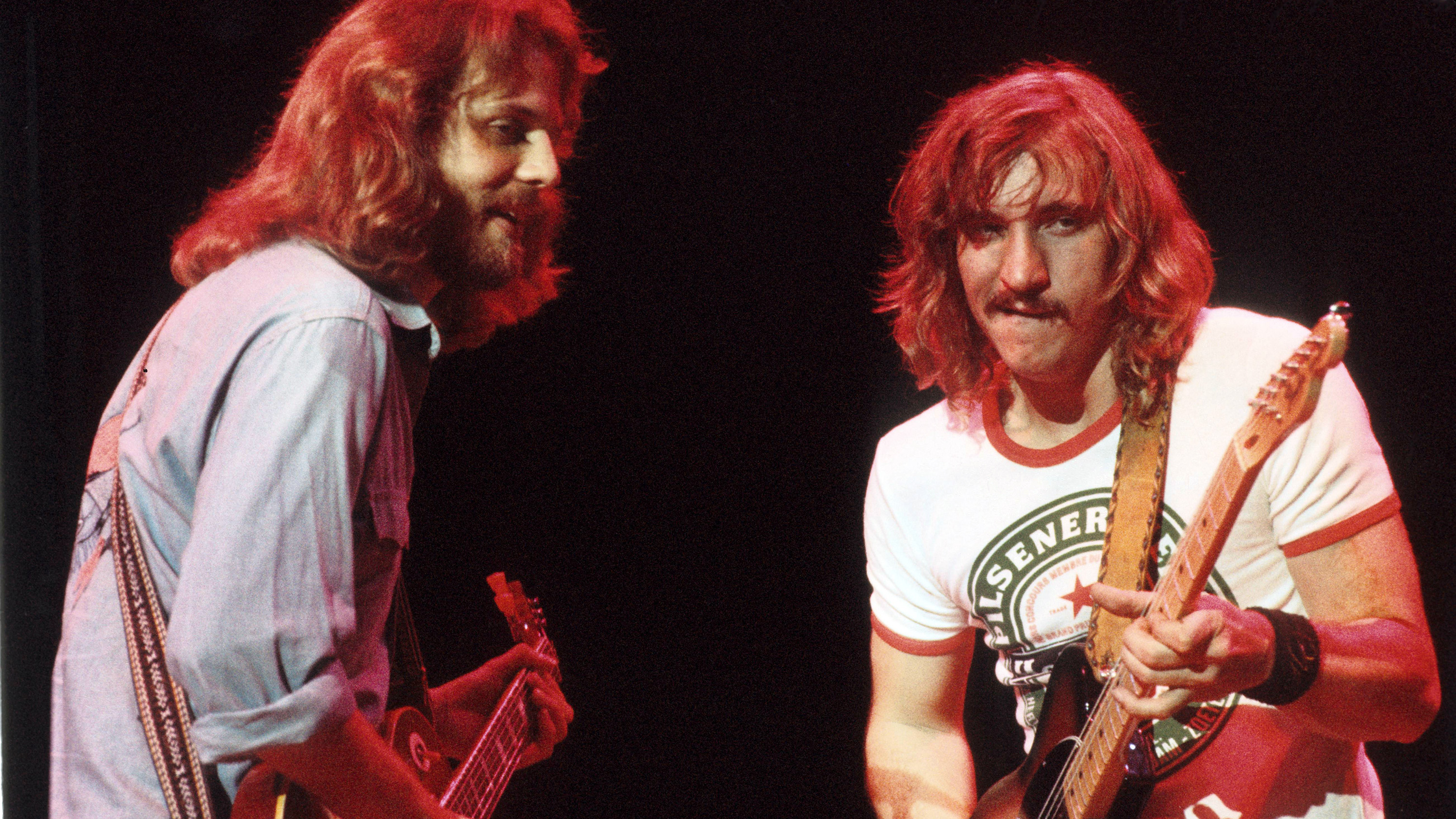

“Life in the Fast Lane” became a showcase for Joe Walsh, who had recently replaced Bernie Leadon in the band. Don Henley noted the song’s origin in Walsh’s guitar riff: “That song actually sprang from the opening guitar riff. One day, at a rehearsal, Joe just busted out that crazy riff and I said, ‘What in the hell is that? We’ve got to figure out some way to make a song out of that!’” Lyrically, they crafted a narrative about a jaded, wealthy couple living a life of excess. Henley and Frey’s songwriting partnership was so seamless at this time that Henley couldn’t recall specific lyrical contributions, describing their creative process as “telepathy.”

One of These Nights (1975)

Eagles One of These Nights album art

Eagles One of These Nights album art

As the Eagles began working on their fourth album, disco’s growing popularity influenced Henley and Frey. They aimed to capture the mood of post-Watergate America with a song that incorporated disco elements while retaining their signature guitar sound. “We thought, ‘Well, how can we write something with that flavor, with that kind of beat, and still have the dangerous guitars?’” Henley explained. “We wanted to capture the spirit of the times.”

The R&B flavor of “One of These Nights” wasn’t entirely new territory for the band, as Henley and Frey were both soul music enthusiasts. Bob Seger, a friend and fellow Detroit native, noted, “Glenn loved Al Green and Otis Redding. And ‘One of These Nights’ was kind of a soul song.” Don Felder contributed the song’s distinctive bass line, which he then taught to Randy Meisner, along with a sharp guitar solo that enhanced the track’s edge. “One of These Nights,” perhaps the most unexpected Eagles single, reached Number One. Frey considered it “my favorite Eagles record” and “a breakthrough song”: “We made a quantum leap with ‘One of These Nights.’”

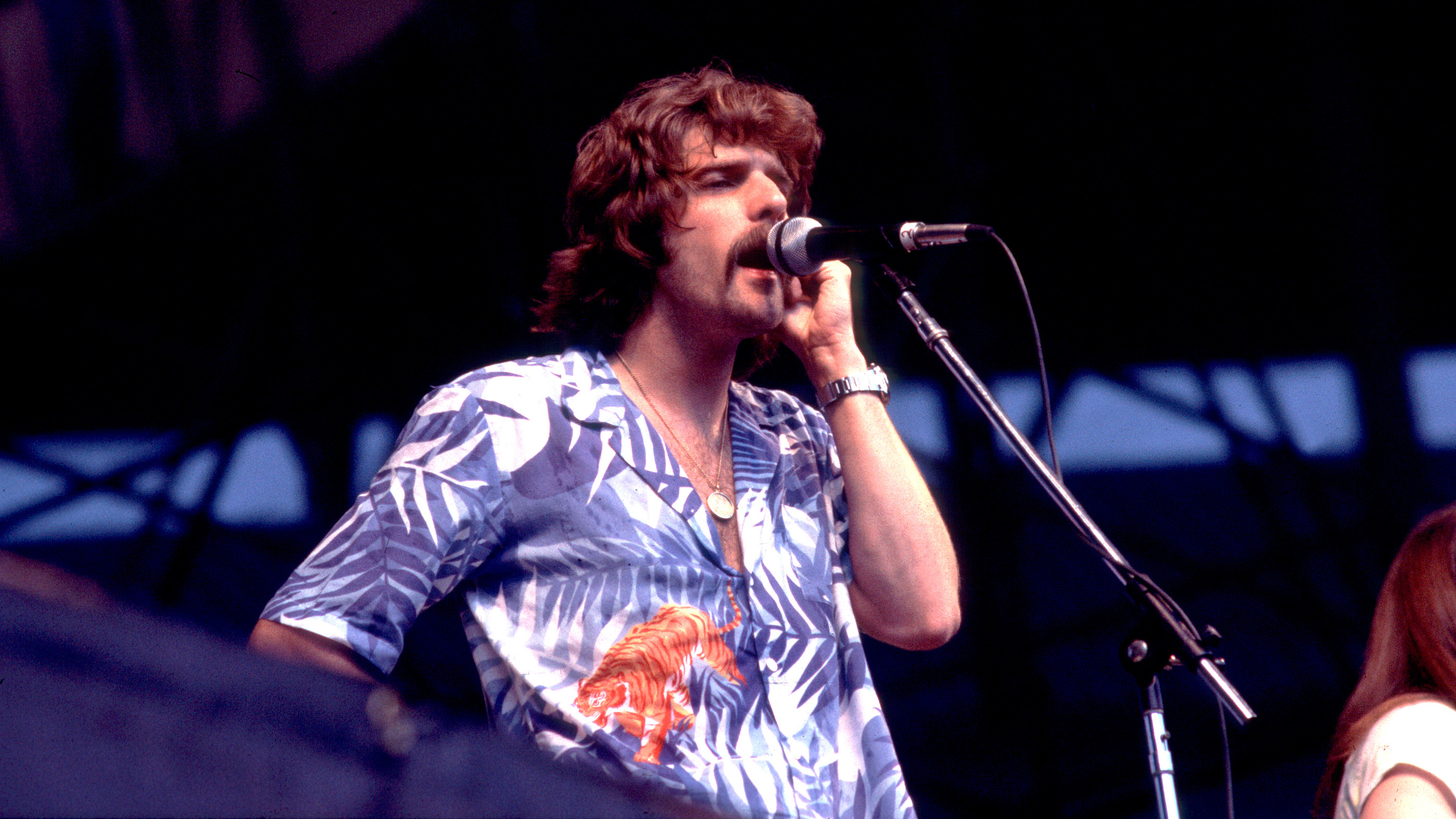

Heartache Tonight (1979)

Eagles Heartache Tonight Doug Griffin photo

Eagles Heartache Tonight Doug Griffin photo

“Heartache Tonight,” a high-energy, sing-along track, had a typically drawn-out development process. Frey and J.D. Souther laid the groundwork, drawing inspiration from Sam Cooke records. Souther recalled, “Glenn started clapping his hands and singing and I joined in, until the first verse felt right.” Later, Bob Seger joined them in Aspen. “They already had [most of] the lyrics, and I started singing really hard, ‘We can leave it in the parking lot/But either way there’s gonna be a heartache tonight!’ and Don said, ‘That’s it – we’re done.’”

To achieve the song’s impactful percussion, Henley employed a unique studio technique. Schmit described the scene: “Henley laid down on the floor of the studio, holding a marching-band-style drum on his chest and beating it with a mallet. He did that forever. It took a long time.” This dedication to sonic detail contributed to the song’s powerful impact.

I Can’t Tell You Why (1979)

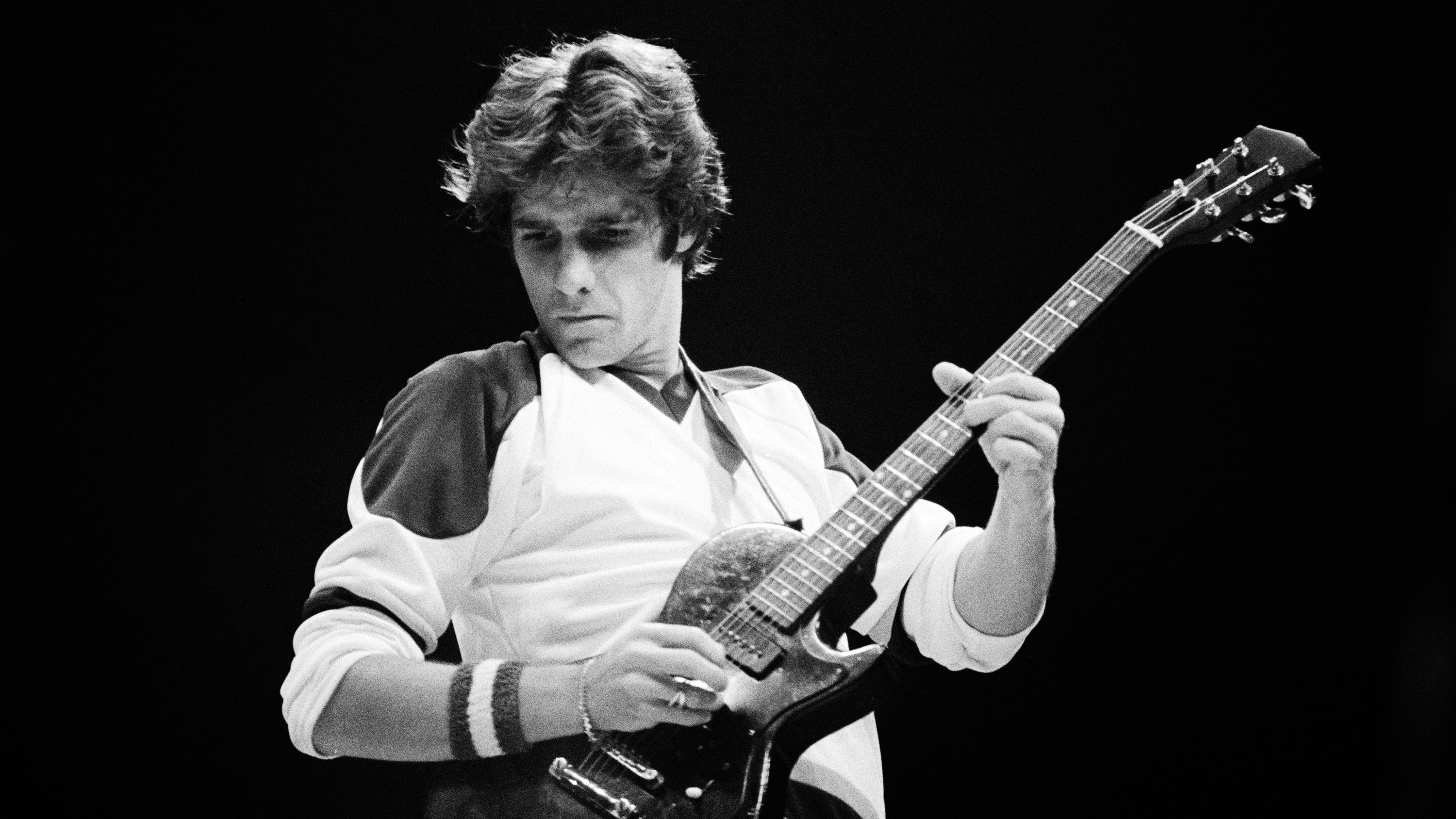

By 1977, the relentless pace of the Eagles’ career began to take its toll. Randy Meisner, in particular, was feeling the strain, suffering from stomach ulcers and chronic pain. Following a tour argument with Frey, Meisner left the band. “I won’t go into real details,” Meisner said in 2008, “But that was kinda the end.”

As the band started recording The Long Run in Miami, one of the first songs they completed featured Timothy B. Schmit, Meisner’s replacement, on lead vocals. Schmit shared the personal context of the song: “I was going through a rough emotional time. I was young and confused about how to make relationships function, and this song was a vent for my melancholia.” When Schmit was slow to finish the lyrics, Henley stepped in, offering a lesson in the band’s demanding work ethic. “Don came up one day and said, ‘I think I finished this.’ It was a good lesson for me. Don said, ‘Reality check.’” “I Can’t Tell You Why,” with its smooth, soft-soul feel, was later covered by R&B artists Howard Hewett and Gerald Alston, highlighting its genre-crossing appeal.

The Long Run (1979)

Eagles The Long Run album art

Eagles The Long Run album art

Henley and Frey’s appreciation for soul music is evident in “The Long Run,” the title track of their album of the same name. The song’s steady groove evokes vintage Stax Records and Tyrone Davis’s 1975 hit “Turning Point.” Its resilient tone carried a hint of defiance. “Despite the extraordinary success of Hotel California, we were collectively in a pretty dark place during the making of The Long Run,” Henley admitted. “We were beginning to see press articles about how we were passé.”

Despite its theme of endurance, The Long Run was followed by a 14-year hiatus for the Eagles. Henley humorously acknowledged this irony in 2003: “Here we are…still going strong. The long run, indeed.” The song itself stands as a testament to their musical roots and their ability to adapt and evolve while staying true to their core sound.

Tequila Sunrise (1973)

Eagles Tequila Sunrise Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

Eagles Tequila Sunrise Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

“Tequila Sunrise,” a classic from Desperado, is a poignant, country-tinged ballad about using alcohol to cope with lost love. Frey primarily wrote the song and delivered the lead vocals with a direct yet tender quality, his subtle vibrato adding a touch of hope to the underlying melancholy.

In the 2003 Eagles compilation, The Very Best Of, Henley revealed Frey’s initial hesitation about the song: “Frey ‘was ambivalent about it because he thought that it was a bit too obvious or too much of a cliché because of the drink that was so popular then.'” However, Frey eventually embraced the song, stating, “I love the song. I don’t think there’s a single chord out of place.” “Tequila Sunrise” has become a beloved Eagles staple, showcasing their ability to blend country influences with their signature harmonies and songwriting.

Best of My Love (1974)

Eagles Best of My Love Paul Natkin photo

Eagles Best of My Love Paul Natkin photo

The creation of “Best of My Love” involved a transatlantic collaboration. J.D. Souther was at producer Peter Asher’s L.A. home when Henley called from London with an urgent request: “Can you get on a plane? We need a bridge.” Souther flew to London the next day to help the band complete the ballad. Initially, there was skepticism about its commercial potential. “Someone at Asylum [the Eagles’ label] told us it could never be a single – too long, too slow, steel guitar, not enough drums,” Souther recalled.

However, a Michigan DJ’s decision to play the song on air sparked listener demand, and “Best of My Love” gained momentum, becoming the Eagles’ first Number One single. “People requested it, and there you go,” Souther said. “It’s a pretty song that feels true.” Its success defied industry expectations and demonstrated the power of listener connection with authentic, emotionally resonant music.

Take It to the Limit (1975)

Eagles Take It to the Limit Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

Eagles Take It to the Limit Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

“Take It to the Limit,” one of the Eagles’ most cherished ballads, originated from a moment of late-night inspiration for Randy Meisner at his L.A. home. “I was feeling kind of lonely and started singing ‘All alone at the end of the evening, and the bright lights have faded to blue,’” he recalled. “And it went from there.” Henley and Frey assisted in completing the song.

During recording, producer Bill Szymczyk drew inspiration from Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes’ soul ballad “If You Don’t Know Me by Now.” At the song’s climax, Meisner reached and sustained a soaring high note. Szymczyk recounted Meisner’s reaction: “Randy said, ‘If it’s a hit, I’m going to have to hit that note every night.’ Which is exactly what happened.” “Take It to the Limit” became a signature song for Meisner, showcasing his vocal range and emotional depth, while also highlighting the Eagles’ ability to craft powerful and enduring ballads.

In the City (1979)

Joe Walsh initially wrote “In the City,” a driving rock song about escaping urban dreariness, with songwriter Barry De Vorzon for the soundtrack of the 1979 film The Warriors. As the Eagles began working on The Long Run, Walsh faced writer’s block, according to producer Bill Szymczyk. “That’s the only song he had,” Szymczyk said.

Since neither the band nor most audiences had seen the movie or heard its soundtrack, the Eagles re-recorded “In the City,” creating a more polished and Eagles-esque version. Frey explained, “I always liked the song and thought it could have been an Eagles record, and so we decided to make it one.” The Eagles’ rendition brought “In the City” to a wider audience, showcasing Walsh’s rock sensibilities within the band’s established sound.

Witchy Woman (1972)

Eagles Witchy Woman performance

Eagles Witchy Woman performance

Bernie Leadon conceived the distinctive tribal-sounding riff of “Witchy Woman” while touring Cape Cod with his previous band, the Flying Burrito Brothers. He later presented it to Henley, who described it as having “a Hollywood-movie version of Indian music – you know, the kind of stuff they play when the Indians ride up on the ridge while the wagon train passes below. It had a haunting quality.”

Henley wrote the lyrics while ill with the flu, drawing inspiration from Zelda Fitzgerald and women he encountered at L.A. clubs like the Troubadour. “An important song for me,” Henley noted. “It marked the beginning of my professional songwriting career.” “Witchy Woman” became a signature early Eagles track, showcasing their ability to blend diverse musical influences into a unique and captivating sound.

James Dean (1974)

Eagles James Dean Richard McCaffrey photo

Eagles James Dean Richard McCaffrey photo

“James Dean” pays tribute to the iconic embodiment of Old Hollywood cool. “You were the lowdown rebel if there ever was/Even if you had no cause,” Frey sang, capturing Dean’s rebellious image. Henley admitted, “The other guys had evidently studied him. I had seen most of Dean’s movies, but I somehow missed the whole icon thing.”

Jackson Browne initiated the song after seeing singer-songwriter Tim Hardin perform live, and Henley, Frey, and J.D. Souther collaborated to complete it. Frey considered the line “I know my life would look all right if I could see it on the silver screen” the song’s highlight, reflecting on the idealized image of life presented in movies. “James Dean” blends a boogieing groove with insightful lyrics, capturing the mystique and allure of its subject.

On the Border (1974)

Eagles On the Border album art

Eagles On the Border album art

For “On the Border,” the title track of their album, the Eagles aimed for a “Temptations feel,” according to producer Bill Szymczyk. Credited with playing “T.N.T.S.” (Tanqueray and tonics) during the session, Szymczyk captured the song’s loose, improvisational vibe. Henley described the song as “a clash of styles and influences,” landing somewhere between Sly Stone and Neil Young.

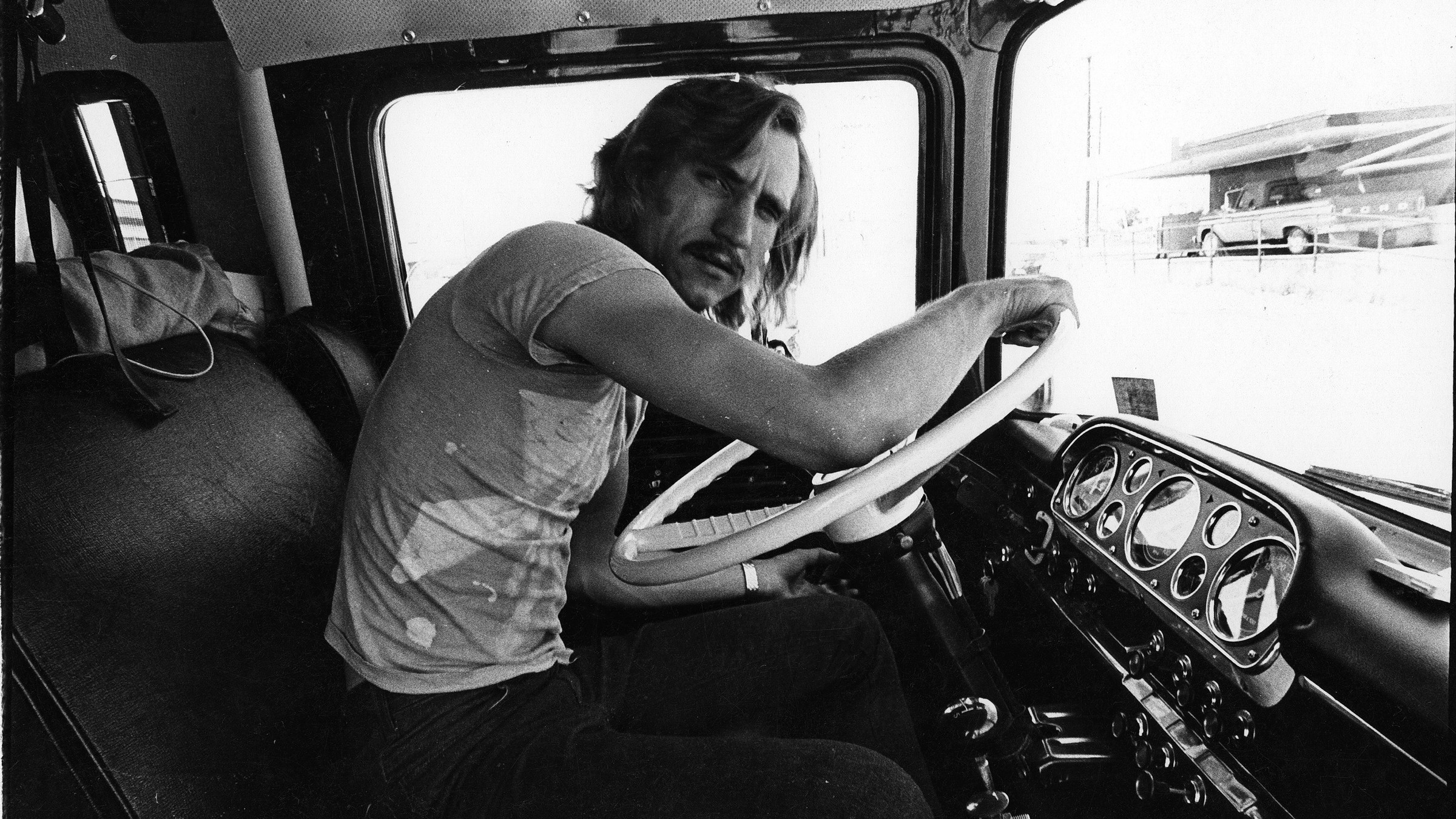

“I remember it was one of the last things to be recorded, and I had come up against an unmovable deadline,” Henley recalled. “So I somehow got my hands on a truck-driver pill called a Black Molly and stayed up all night completing the song. That’s how badly I wanted to go home.” “On the Border” embodies a raw, funky energy, reflecting the band’s willingness to experiment and push their musical boundaries.

The Sad Cafe (1979)

Eagles The Sad Cafe Michael Putland photo

Eagles The Sad Cafe Michael Putland photo

During the One of These Nights sessions in 1975, producer Bill Szymczyk implemented a “Six O’Clock Rule,” prohibiting drinking or drugs before 6 PM. By the Long Run sessions in 1979, even this rule couldn’t prevent the recording process from becoming protracted and challenging. Inspired by rumors that Fleetwood Mac was working on a double album (Tusk), the Eagles initially aimed for a double LP themselves. However, eighteen months of work yielded a single album that often reflected their weariness and internal tensions.

“The Sad Cafe,” the album’s closing track, serves as an elegy for the L.A. music scene that birthed them. J.D. Souther explained, “It’s more than anything else about losing your innocence, our innocence. It’s a real place and still a favorite restaurant – Dan Tana’s – where for years we huddled in the back booth and schemed, dreamed and laughed more than seems possible.” The title came from Carson McCullers’ The Ballad of the Sad Café. Its smooth-jazz arrangement, featuring a saxophone solo by David Sanborn, foreshadowed Frey’s later solo work.

After the Thrill Is Gone (1975)

Eagles After the Thrill is Gone David Tan photo

Eagles After the Thrill is Gone David Tan photo

“After the Thrill Is Gone,” a somber highlight from One of These Nights, directly references the B.B. King blues classic “The Thrill Is Gone.” “We wanted to explore the aftermath,” Henley explained. “We know that the thrill is gone – so, now what?” The song became somewhat autobiographical, reflecting their feelings after the initial excitement of success had faded.

Henley and Frey collaborated equally on the song, with Frey writing the verses and Henley crafting the bridge. Frey described it as “a sleeper” and noted that One of These Nights as an album involved “a lot of self-examination, hopefully not too much.” “After the Thrill Is Gone” is a poignant reflection on the complexities of long-term relationships and the inevitable shifts in emotions over time.

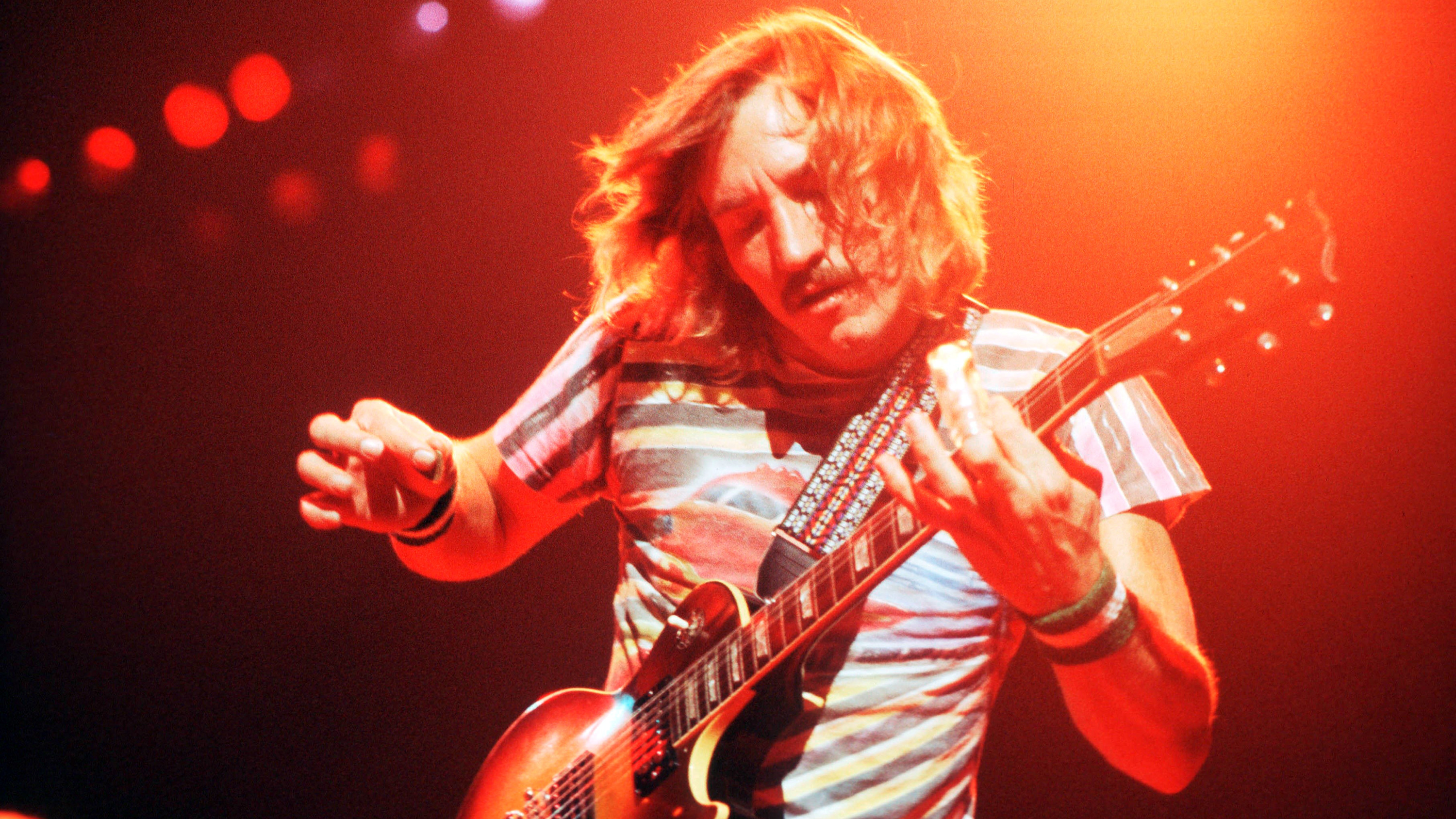

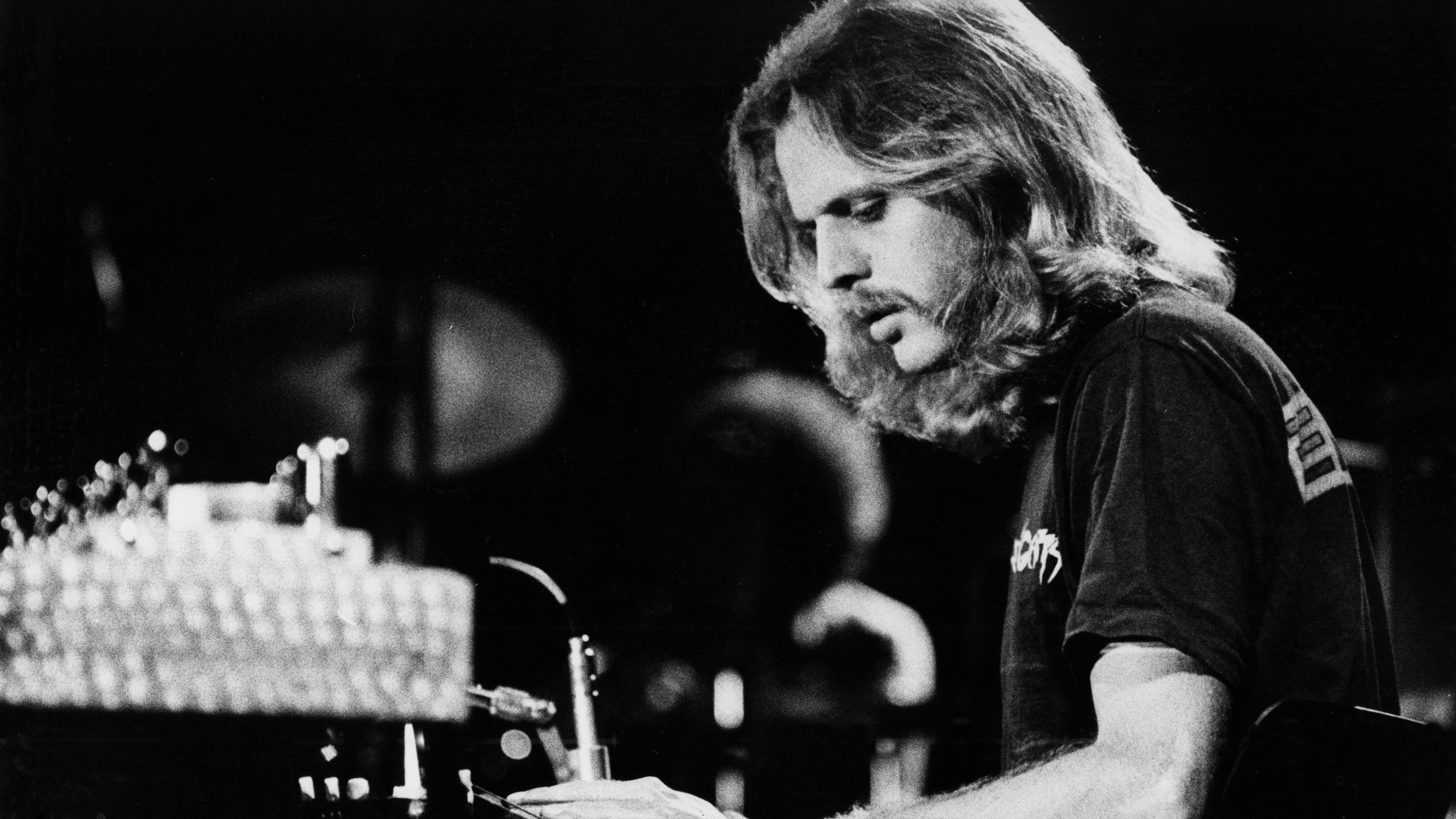

Hollywood Waltz (1975)

Joe Walsh Eagles Hollywood Waltz performance

Joe Walsh Eagles Hollywood Waltz performance

By the Eagles’ fourth album, Bernie Leadon, the band member with the strongest country music background, was feeling increasingly disconnected from the band’s rock-oriented direction. One of These Nights featured two of his songs: “I Wish You Peace,” co-written with Patti Davis, and “Hollywood Waltz,” co-written with his brother Tom Leadon.

“Henley and Frey liked the song, but they didn’t like the story,” Bernie Leadon explained. “So they rewrote it as ‘Hollywood Waltz.’” Sung by Henley with echoes of the country classic “Tennessee Waltz,” “Hollywood Waltz” is a lament for the darker side of the California dream. It reflects Leadon’s traditional country sensibilities and the band’s evolving sound.

Try and Love Again (1976)

Eagles Try and Love Again GAB Archive photo

Eagles Try and Love Again GAB Archive photo

Randy Meisner was experiencing a divorce during the Hotel California sessions, and his bandmates encouraged him to contribute material despite his personal turmoil. Out of this difficult period came “Try and Love Again,” a meditative ballad. “I sat around one evening and got a little high and started playing something and thought, ‘Is this OK?’” he recalled. “I brought it to rehearsal, and they said, ‘That’s pretty good.’”

The song, dealing with the struggle to move on after a relationship ends, became, somewhat ironically, Meisner’s final contribution to the group, as he departed the following year. “Try and Love Again” is a deeply personal and vulnerable track, showcasing Meisner’s songwriting and vocal talents.

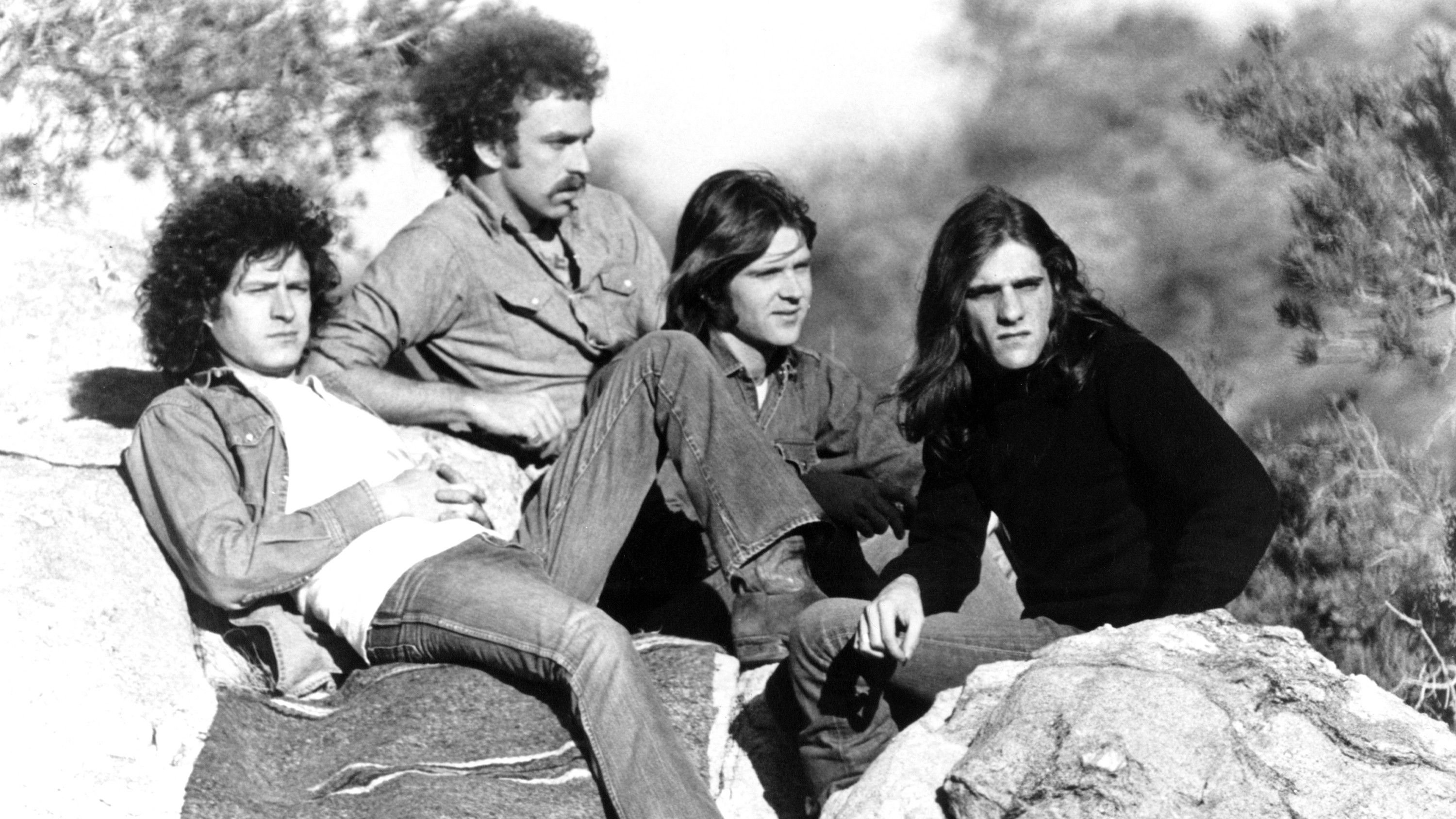

Doolin-Dalton (1973)

Eagles Doolin Dalton album art

Eagles Doolin Dalton album art

“Doolin-Dalton,” the opening track of Desperado, sets the album’s Western theme with Frey’s mournful harmonica and a narrative about the Dalton Gang. The song recounts the story of the real-life Dalton Brothers gang, who met their demise in 1892 after a failed bank robbery attempt. The inspiration came from a book given to co-writer Jackson Browne by Ned Doheny.

Leadon connected the outlaw theme to the band’s own experiences: “All the music artists who’d been in the folk movement…several of them testified before the House Un-American Activities [Committee]. We all knew people who had been busted for pot, who had been prosecuted for avoiding the draft. So I think that we all felt some affinity with the concept of being outlaws.” “Doolin-Dalton” establishes the album’s concept and sets a tone of romanticized outlaw life.

Wasted Time (1976)

Eagles Wasted Time Ellen Poppinga photo

Eagles Wasted Time Ellen Poppinga photo

“Nothing inspires or catalyzes a great ballad like a failed relationship,” Henley stated about “Wasted Time,” a tender Hotel California track inspired by his breakup with jewelry designer Loree Rodkin. “It’s a very empathetic song.” The midtempo piano ballad blends Philly soul influences with the introspective sound of early Eagles tracks like “Desperado.”

“Wasted Time” highlights Henley’s vocal abilities, channeling the song’s pathos. Frey once described Henley as “our Teddy Pendergrass,” praising his ability to convey emotion through his voice. The song’s dramatic impact led the band to include an instrumental reprise as a suite leading into the second half of the Hotel California album.

Those Shoes (1979)

Eagles Those Shoes Fotos International photo

Eagles Those Shoes Fotos International photo

“On the surface, the song was about the singles scene,” Henley said of “Those Shoes” from The Long Run. However, the footwear imagery carried a deeper meaning: “At that time, all the girls were wearing Charles Jourdan shoes – the ones with the little ankle straps. We said, ‘Well, it’s not enough just to write about that; we have to turn it into a metaphor for women standing on their own two feet, so to speak, and taking responsibility for their own lives, their own losses.’”

Driven by Walsh and Felder’s talk-box guitars, “Those Shoes” gained renewed popularity later as a sample source for hip-hop artists, including the Beastie Boys. The song’s funky groove and metaphorical lyrics gave it a lasting appeal across genres.

The Last Resort (1976)

“The Last Resort,” the closing track of Hotel California, took seven months to complete, becoming “the last piece of the Hotel California puzzle,” according to Frey. He called it “Henley’s opus,” a meditation on environmental degradation and the destructive consequences of Manifest Destiny.

“I’d been reading articles and doing research about the raping and pillaging of the West by mining, timber, oil and cattle interests,” Henley recalled. “But I was interested in an even larger scope for the song, so I tried to go ‘Michener’ with it.” While Henley was never fully satisfied with the musical arrangement, producer Bill Szymczyk considered its power comparable to “Hotel California” itself. “The Last Resort” offers a sweeping, critical perspective on American history and environmental responsibility.

The Disco Strangler (1979)

Eagles Disco Strangler performance

Eagles Disco Strangler performance

Like many rock musicians in the late 1970s, the Eagles held ambivalent views towards disco. This sentiment surfaced in “The Disco Strangler,” a dark, pulsating track from The Long Run. The song tells the story of a woman “lookin’ for the good life/Dressed to kill” who meets a sinister fate in a disco club at the hands of a stranger.

Producer Bill Szymczyk described the song’s narrative: “It’s ‘watch out for the guy on the date – he might have a knife.’” Felder’s arrangement subtly parodies disco rhythms, creating an ironically mordant piece. Schmit noted, “That album has some quirky songs,” highlighting the band’s willingness to explore darker and more unconventional themes.

Ol’ 55 (1974)

Eagles Ol 55 Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

Eagles Ol 55 Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

Tom Waits, known for his gravelly vocals and unconventional style, wasn’t a typical mainstream artist in the 1970s. However, after David Geffen played a Waits demo for Frey, the Eagles were inspired to record Waits’s melancholic “Ol’ ’55,” marking one of the earliest covers of a Tom Waits song. (Eagles fans famously booed Waits when he opened for the band in 1975).

“It’s such a car thing,” Frey said of the song, which they gave a steel-guitar infused makeover. “I loved the idea of driving home at sunrise, thinking about what had happened the night before.” The Eagles’ rendition of “Ol’ 55” introduced Waits’s songwriting to a wider audience and showcased their ability to interpret diverse material in their own style.

Victim of Love (1976)

Eagles Victim of Love Bobby Bank photo

Eagles Victim of Love Bobby Bank photo

The Eagles were not known for spontaneous, live-in-the-studio recordings. However, “Victim of Love,” a blistering Hotel California rocker, was a rare exception. Originating as a Felder instrumental titled “Iron Lung,” the track was recorded live (“v.o.l. is five piece live” etched into early vinyl pressings).

Felder initially expected to sing lead vocals, but manager Irving Azoff informed him that Henley would take the lead. Felder later wrote, “Don stepped up and sang, and it was immediately apparent to everyone, especially me, that he should sing it – even though, deep down, I wasn’t thrilled at losing my slot.” Henley’s powerful vocal performance solidified “Victim of Love” as a raw and energetic outlier in the Eagles’ catalog.

Bitter Creek (1973)

Eagles Bitter Creek Michael Ochs Archives photo

Eagles Bitter Creek Michael Ochs Archives photo

“The basic premise” of Desperado, Henley explained, “was that, like the outlaws, rock & roll bands lived outside the ‘laws of normality’ – we were not part of ‘conventional society.’ We all went from town to town, collecting money and women, the critical difference being that we didn’t rob or kill anybody for what we got; we worked for it.”

To flesh out the Desperado concept album, Henley and Frey encouraged bandmates to contribute songwriting. Leadon recalled, “I’m not sure which one of them started to write some songs on this topic. As the songs came into focus, Glenn decided to try to fill in some blanks. I remember him kind of assigning song titles or ideas to us. He offered, or gave, me the title ‘Bitter Creek,’ based on a man in the Dalton gang named [George] Bittercreek Newcomb. I didn’t write it about him – I just used the phrase ‘Bitter Creek,’ which I quite liked.” “Bitter Creek,” with its haunting cantina feel, is a deep cut highlight of Desperado and a significant contribution from Leadon. Despite its artistic ambition, Desperado initially confused some, with David Geffen questioning its commercial viability after the success of their debut album.

My Man (1974)

Eagles My Man Waring Abbott photo

Eagles My Man Waring Abbott photo

Bernie Leadon had just arrived in London for the On the Border sessions when he learned of Gram Parsons’s death. “This was my first peer who had died, so I was quite set back by it,” Leadon said. He began writing “My Man” as a tribute to his former Flying Burrito Brothers bandmate.

When the Eagles reconvened in Los Angeles to finish the album, Leadon hadn’t completed the lyrics. “They said, ‘OK, we’re going to go to dinner, and you’re gonna stay here and finish the song,’” Leadon laughed. “Henley gave me a clue for something to tie in, the Gram song ‘Hickory Wind.’ They came back, and I was like, ‘OK, let’s put the vocal on.’” “My Man” is a heartfelt and personal tribute, reflecting Leadon’s grief and admiration for Parsons.

Most of Us Are Sad (1972)

Eagles Most of Us Are Sad Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

Eagles Most of Us Are Sad Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

During an early Eagles rehearsal when original songs were scarce, Frey played “Most of Us Are Sad” on guitar. “I thought, ‘Well, that’s a really interesting song,’” Leadon recalled. “It really does express something truthful – that a lot of people probably are sad but don’t express it.”

For the album version, Randy Meisner took the lead vocal, his softer, higher voice enhancing the lyrics’ mournful quality. Leadon noted, “We had a natural tenor singer in Randy Meisner. And in Henley too. So we had two guys that could go up high and not be strained-sounding.” “Most of Us Are Sad” is a poignant early Eagles ballad, showcasing their harmonies and introspective songwriting.

Love Will Keep Us Alive (1994)

Eagles Love Will Keep Us Alive Jeff Wheeler photo

Eagles Love Will Keep Us Alive Jeff Wheeler photo

During the Eagles’ 14-year hiatus, Schmit and Felder collaborated on demos for a supergroup with Max Carl and Paul Carrack. “Everything was fine and dandy, when much to my chagrin, they came to their senses and put the Eagles back together,” Carrack recalled. “That was the end of my little project.”

Although the supergroup didn’t materialize, Schmit asked if he could use “Love Will Keep Us Alive,” co-written by Carrack, Pete Vale, and Jim Capaldi. Featuring Schmit’s lead vocal, it became a hit on the Adult Contemporary charts after the Eagles reunited. “Love Will Keep Us Alive” became a symbol of the Eagles’ successful reunion and their continued ability to create emotionally resonant music.

How Long (2007)

Eagles How Long Allocca Starpix photo

Eagles How Long Allocca Starpix photo

When the Eagles reunited to record Long Road Out of Eden in 2007, their first studio album since The Long Run, they amassed a wealth of material, creating a double album ranging from political commentary to personal reflections. Walsh joked it could have been a triple album, highlighting their creative output.

During the album’s creation, Frey’s family discovered a clip of the Eagles performing J.D. Souther’s obscure song “How Long.” Souther recalled, “Glenn’s wife, Cindy, said, ‘That sounds like a classic Eagles hit – did you ever record it?’ Glenn said, ‘No, in those days, if one person put a song on an album, the other person didn’t.’” Written in 1969, Souther’s song was inspired by a soldier in Vietnam imprisoned for murder after going AWOL, his girlfriend counting down the days for his return that would never come. The Eagles’ recording of “How Long” brought a lost gem to light and showcased their enduring connection to Souther’s songwriting.

Outlaw Man (1973)

Eagles Outlaw Man Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

Eagles Outlaw Man Gijsbert Hanekroot photo

To further enhance the Western theme of Desperado, the Eagles recorded “Outlaw Man” by singer-songwriter David Blue. Frey had recently appeared on Blue’s album, Nice Baby and the Angel, which included the original version of the song. Leadon explained, “We all heard Blue’s album before it was released, and I think Glenn suggested the song fit the theme of the album and that we should work it up.”

The Eagles’ cover of “Outlaw Man” was even more powerful than Blue’s original, adding a thunderous energy to Desperado. Leadon noted it filled a need for “some rockers” on the album, as they weren’t writing many at the time. “Outlaw Man” became a standout track, exemplifying the Eagles’ ability to reinterpret and amplify existing songs.

The Greeks Don’t Want No Freaks (1979)

Eagles The Greeks Dont Want No Freaks performance

Eagles The Greeks Dont Want No Freaks performance

“The Greeks Don’t Want No Freaks” emerged late in the Long Run sessions. Schmit suggested inspiration came from watching Animal House. Whatever the source, the song is an atypically loose, two-and-a-half-minute tribute to 1960s garage rock, complete with a Farfisa organ and backing vocals from Jimmy Buffett.

“That was a song where you didn’t have to be that precise,” Schmit said. “Looseness was inherent in it. It was so bizarre. But it was so much fun.” “The Greeks Don’t Want No Freaks” offers a lighthearted and unexpected moment in the Eagles’ discography, showcasing their playful side.

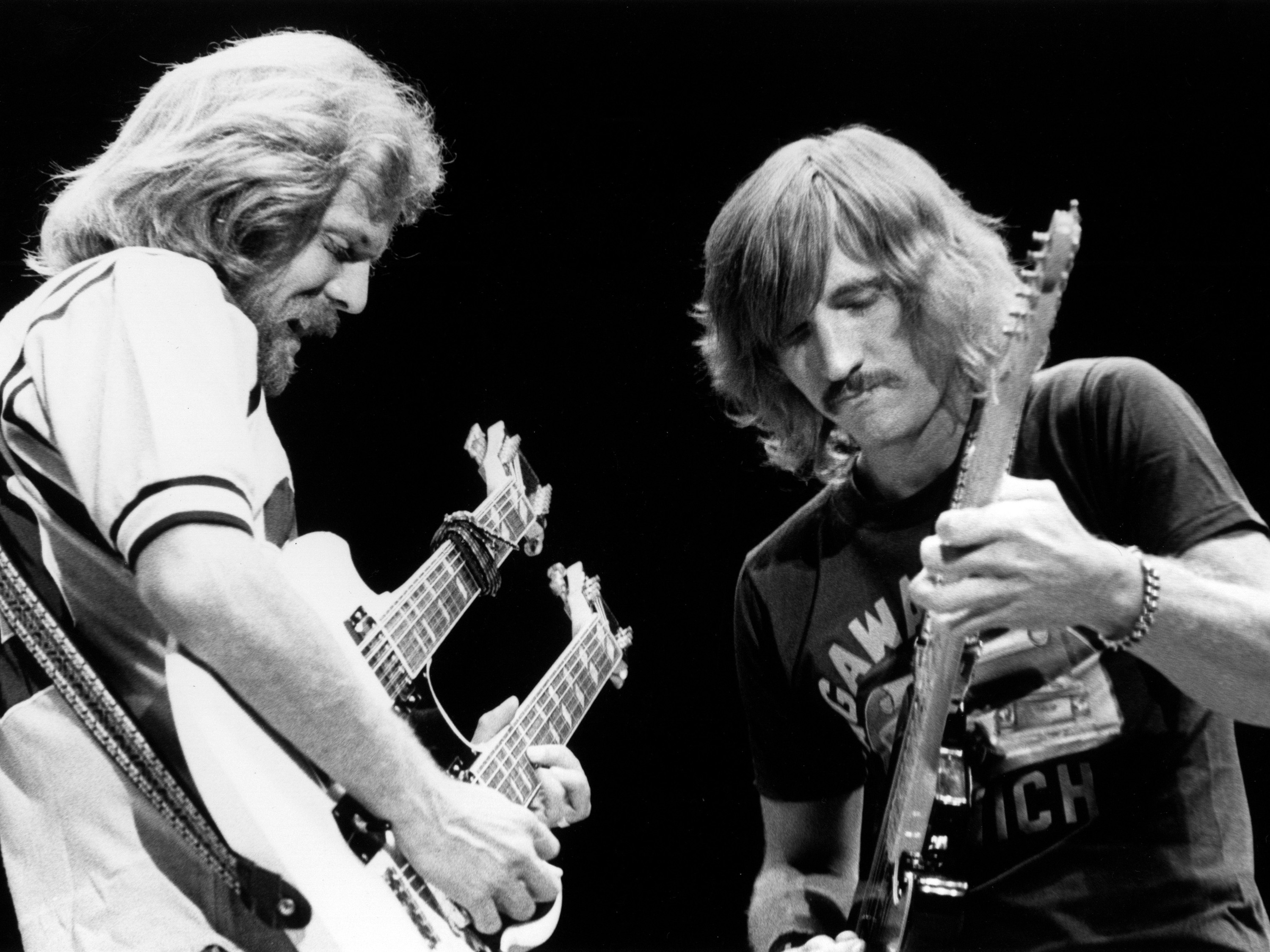

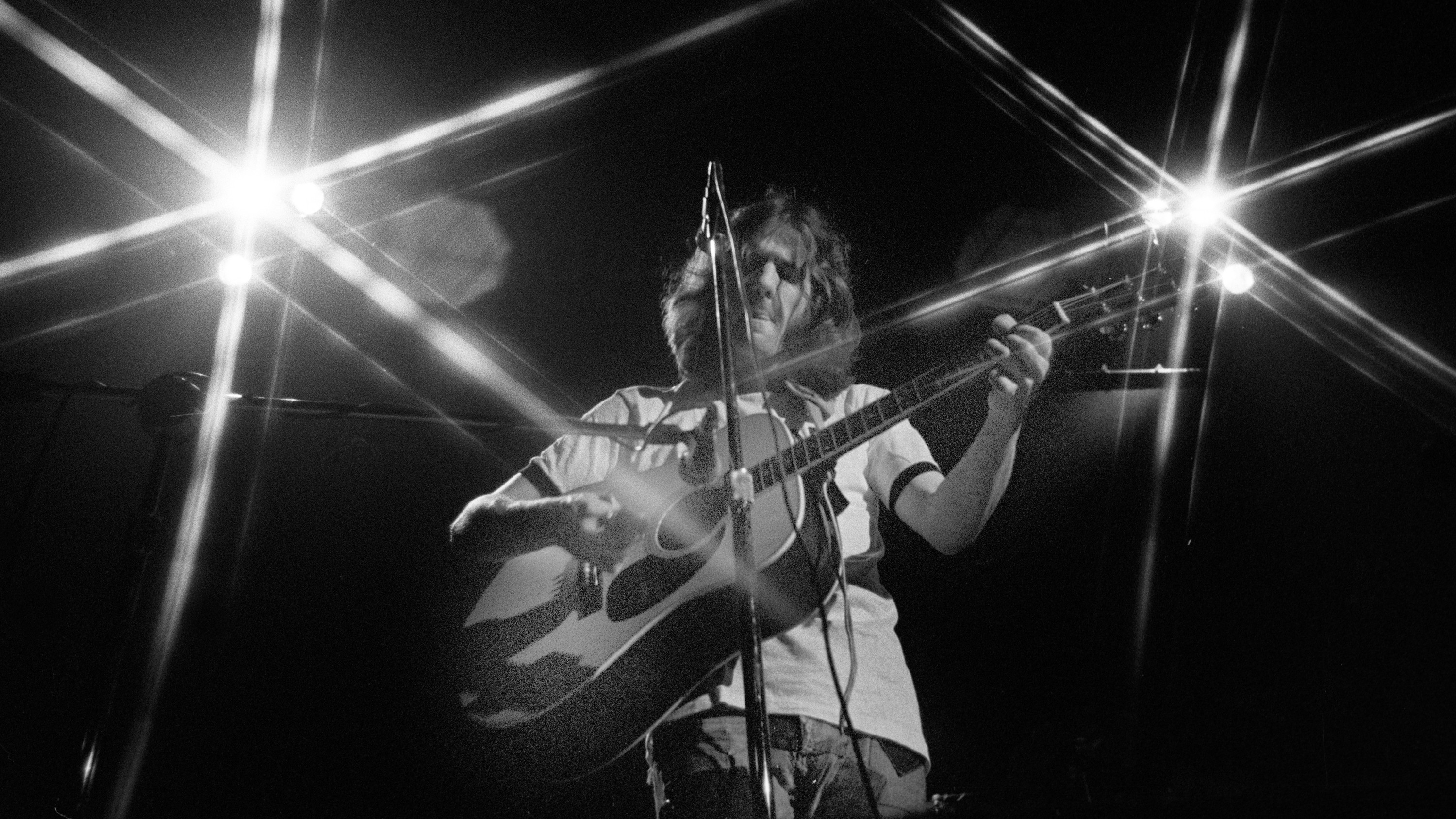

Pretty Maids All in a Row (1976)

“Pretty Maids All in a Row,” an uncharacteristic ballad from Joe Walsh, explores regret and reflection on life. Walsh and his bandmates delved into lush soul orchestration for the track, while Walsh contributed a soaring bluesy slide-guitar solo.

Released as the B-side to “Hotel California,” “Pretty Maids All in a Row” served as a spiritual companion piece, both songs exploring themes of lost love. Walsh described it as “kind of a melancholy reflection on my life so far. And I think we tried to represent it as a statement that would be valid for people from our generation on life so far.” It is a deeply personal and introspective song from Walsh, showcasing a different side of his musicality.

Please Come Home for Christmas (1978)

Eagles Please Come Home for Christmas Paul Natkin photo

Eagles Please Come Home for Christmas Paul Natkin photo

In mid-1978, with The Long Run sessions dragging on, Asylum Records requested a stopgap release. “This was in September, so we said, ‘Let’s give them a Christmas song,’” producer Bill Szymczyk recalled. Henley, a fan of Charles Brown’s 1961 R&B hit “Please Come Home for Christmas,” suggested a cover.

The Eagles recorded a heartfelt version as a single in Miami, despite the un-Christmassy weather. Frey joked, “It was hot as hell. Perfect for a Christmas record.” Their rendition of “Please Come Home for Christmas” became a holiday classic, demonstrating their versatility and ability to interpret songs from diverse genres.

Saturday Night (1973)

Eagles Saturday Night RB photo

Eagles Saturday Night RB photo

Randy Meisner conceived “Saturday Night” while reflecting on his youth. “I was sitting there one night, and I came up with the line ‘What ever happened to Saturday night?’” the bassist recalled. “When I was younger, I would be out partying, and with girls and having fun. And that’s what it was about: Whatever happened to it? And the answer was, ‘You’re older now.’”

Leadon’s mandolin and Henley’s melancholic vocals lend a gentle, heartbroken quality to the soft country waltz. “Saturday Night” personalizes Desperado‘s themes of drifting and longing, adding a touch of nostalgia and reflection on lost youth.