Most of us can readily recite, “Sing A Song Of Sixpence, a pocketful of rye,” but how many have paused to ponder the peculiar imagery of blackbirds baked in a pie? This seemingly innocent nursery rhyme, ingrained in childhood, harbors layers of potential meanings and a history as rich and complex as a royal banquet. Far from simple children’s verse, “Sing a Song of Sixpence” is a journey through centuries of folklore, culinary extravagance, and perhaps even veiled political commentary.

A Rhyme Through Time: Tracing the Origins of “Sing a Song of Sixpence”

The earliest known printed version of this rhyme appeared in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book. Interestingly, this initial iteration featured “naughty boys” instead of blackbirds, baked in a pie:

Sing a Song of Sixpence,

A bag full of Rye,

Four and twenty Naughty Boys,

Baked in a Pye.

This darker imagery evolved by 1780 when the rhyme expanded to two verses, replacing the boys with birds. By 1784, a four-verse version emerged, introducing the unfortunate maid and her avian assailant. The familiar fifth verse, focused on the maid’s nose being reattached, surfaced in the 19th century, offering two whimsical resolutions – one involving the king’s doctor and the other a helpful wren. This evolution highlights the fluid nature of folklore, adapting and changing across generations.

Image of ¶ Sing a song of sixpence, a pocketful of rye ¶

Image of ¶ Sing a song of sixpence, a pocketful of rye ¶

Sing a Song of Sixpence nursery rhyme text from Roud Folk Song Index 13191.

Blackbirds in a Pie? Deciphering the Culinary and Political Subtext

The bizarre image of birds baked in a pie might seem absurd to modern sensibilities. However, in the 16th century, this “dish” was not entirely out of place. Known as a subtlety or entremet, these creations were not intended for consumption. Instead, they were elaborate displays of culinary artistry and extravagance, designed to impress and showcase the chef’s skill and the court’s opulence. Imagine a pie crust, cooked and presented hot, concealing live birds released upon cutting – a spectacle intended to inspire awe and convey power. This wasn’t about dinner; it was about politics and social signaling, a concept still echoed today in events like the Met Gala, where spectacle and extravagance take center stage.

Artist and Date UnknownWell, it should have been taking up your thoughts because depending on what source you look at, there are layers upon layers of suspected meaning here. No one is certain where it came from, when, or why. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, what is known for a certainty is that the first verse was first put into print in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book:

Artist and Date UnknownWell, it should have been taking up your thoughts because depending on what source you look at, there are layers upon layers of suspected meaning here. No one is certain where it came from, when, or why. According to the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes, what is known for a certainty is that the first verse was first put into print in 1744 in Tommy Thumb’s Pretty Song Book:

Animated illustration of “Sing a Song of Sixpence” nursery rhyme, artist and date unknown.

Shakespeare, Alchemy, and Henry VIII: Exploring Potential Interpretations

While the rhyme’s exact origins remain shrouded in mystery, literary and historical clues offer several compelling interpretations. References in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night (c. 1602) and Beaumont and Fletcher’s Bonduca (1614), where “sing a song o’ sixpence” is used, suggest the phrase was already in common parlance, possibly signifying something trivial or easily dismissed.

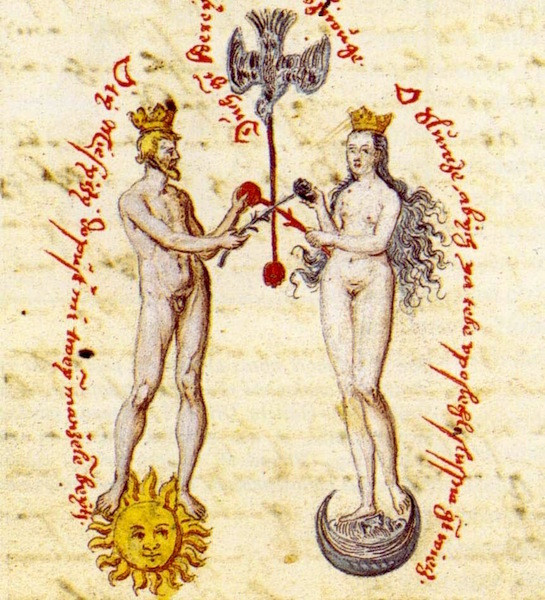

One intriguing theory delves into the realm of alchemy. Proponents suggest the 24 blackbirds symbolize the 24 hours of the day, while the King and Queen represent the sun and moon, respectively. This interpretation hints at alchemical concepts of union and transformation, echoing the “chymical wedding” symbolism.

The Paris Review – Is “The Chemical Wedding” (1616) the First Sci-Fi Story?

The Paris Review – Is “The Chemical Wedding” (1616) the First Sci-Fi Story?

“The Chemical Wedding” book cover, possibly related to alchemical interpretations of the rhyme.

Another, more historically grounded, interpretation connects the rhyme to King Henry VIII and the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s. In this theory, the blackbirds represent monks, and the pie symbolizes a bribe offered to the King. It’s speculated that the Abbot of Glastonbury sent Henry VIII a pie containing deeds to twelve manorial estates in a desperate attempt to curry favor and prevent the dissolution of his abbey.

Furthering the Henry VIII connection, some believe the rhyme reflects the tumultuous relationships of the King. The King is Henry, the Queen is Catherine of Aragon, and the maid represents Anne Boleyn. The blackbird pecking off the maid’s nose is interpreted as a symbolic, less gruesome depiction of Anne Boleyn’s eventual beheading.

Valentine Prinsep, Date Unknown *(I love the way it looks like she’s trying to surreptitiously shove that bread and honey into her face without anyone seeing her)*The other story that centers on Henry is the idea that the King in the song is Henry, the Queen is Catherine of Aragon, and the chambermaid represents Anne Boleyn, with the removal of the nose symbolizing her eventual decapitation. I suppose that tearing off a nose was less gruesome than decapitation and so more acceptable in a children’s rhyme?

Valentine Prinsep, Date Unknown *(I love the way it looks like she’s trying to surreptitiously shove that bread and honey into her face without anyone seeing her)*The other story that centers on Henry is the idea that the King in the song is Henry, the Queen is Catherine of Aragon, and the chambermaid represents Anne Boleyn, with the removal of the nose symbolizing her eventual decapitation. I suppose that tearing off a nose was less gruesome than decapitation and so more acceptable in a children’s rhyme?

Painting “The Queen was in the Parlour” by Valentine Prinsep, illustrating a scene from the nursery rhyme.

Other, more speculative, theories link “Sing a Song of Sixpence” to the invention of moveable type or even as a coded message amongst pirates. While these remain possibilities, it’s equally plausible that the rhyme began as simple nonsense verse, gaining layers of interpretation over time as people sought meaning in its whimsical imagery.

The Enduring Enigma of Sixpence

Ultimately, the true meaning of “Sing a Song of Sixpence” remains elusive. Whether it’s a relic of political satire, alchemical symbolism, historical commentary, or simply a nonsensical rhyme that captured the popular imagination, its enduring appeal is undeniable. Perhaps the beauty of “Sing a Song of Sixpence” lies not in deciphering a definitive meaning, but in the multitude of possibilities it presents, inviting us to delve into history, folklore, and the playful ambiguity of language itself.

Who Knows GIFs | Tenor

Who Knows GIFs | Tenor

Elmo shrugging GIF, representing the uncertainty and mystery surrounding the rhyme’s true meaning.