As a songwriter, the enduring quality of certain songs fascinates me. From the vast ocean of music ever created, why do only a select few continue to resonate across generations? It’s a captivating question, and what better way to explore it than by delving into the history and mechanics of songs that have truly stood the test of time? Let’s embark on this musical journey together, starting with a classic: “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down.” Like many beloved folk songs, its origins are shrouded in mystery, lost to the annals of time. The earliest known recording of this gem was in 1925 by Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers.

Over the years, this song has gathered various aliases – “The Deal,” “Deal Rag,” and others – and has been interpreted and recorded by a diverse array of artists. Notable renditions include those by Doc Watson, Flatt & Scruggs, the New Lost City Ramblers, David Bromberg, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and even an instrumental version by Bob Wills. The beauty of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” lies in its adaptable nature. Its thematic core and structural flexibility have allowed singers to infuse it with a rich tapestry of lyrics, both traditional and newly crafted, ensuring its continued relevance and appeal.

Charlie Poole: The Pioneer

Charlie Poole’s recording, titled “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues,” marked his entry into the commercial music scene and became an instant hit, selling over 100,000 copies – a remarkable feat for that era. Ironically, Poole’s compensation was based on songs recorded, not records sold, a common practice at the time that didn’t fully reward artists for breakout hits. The verses of Poole’s version paint a vivid picture of the traveling musician’s life, juxtaposed with the poignant image of a sweetheart left behind. The chorus introduces the enigmatic “deal,” widely interpreted as a reference to gambling, specifically card games. Online discussions hint at now-obscure card games where letting one’s “deal go down” would have significant consequences.

Consider these evocative lyrics from Poole’s rendition:

Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Down to Memphis, Tennessee

Any old place I hang my hat

Looks like home to me

Now I left my little girl crying

Standing in the door

Throwed her arms around my neck

Saying ‘Honey, don’t you go’

Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Done most everything

I’ve played cards with the King and the Queen

Discard the ace and the ten

Chorus

Oh it’s don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Before my last gold dollar is gone

Now where did you get them high top shoes?

Dress you wear so fine?

Got my shoes from a railroad man

And my dress from a driver in the mine

Who’s gonna shoe your pretty white feet?

Who’s gonna glove your hand?

Who’s gonna kiss your lily white cheeks?

Who’s gonna be your man?

Now Papa may shoe my pretty white feet

Mama can glove my hand

She can kiss my lily white cheeks

‘Til you come back again

Charlie Poole, a pioneer of early country music, banjo player, and known for his influential recording of "Don't Let Your Deal Go Down".

Charlie Poole, a pioneer of early country music, banjo player, and known for his influential recording of "Don't Let Your Deal Go Down".

Album cover showcasing Charlie Poole's music, highlighting his significant contribution to American folk and country music heritage.

Album cover showcasing Charlie Poole's music, highlighting his significant contribution to American folk and country music heritage.

Charlie Poole’s legacy extends far beyond this single song. He is often considered a progenitor of the “outlaw” country music archetype. Emerging from the Piedmont region of Virginia in the interwar period, Poole lived a multifaceted life. Beyond his banjo playing and band leadership, he worked in mills, played baseball, and was rumored to be involved in moonshining. He was consistently portrayed as a hard-living, hard-drinking personality. Despite a relatively short career, cut short by his untimely death due to alcoholism before the age of 40, Poole left behind a rich catalog of around 60 recorded songs. These include folk classics like “Sweet Sunny South,” “Only Old and in the Way,” “Hesitation Blues,” and “You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me.” These recordings are readily accessible online and through compilations available at libraries, such as the San Diego County Library. Two notable CD collections are You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me: Charlie Poole and the Roots of Country Music, featuring original recordings and modern interpretations, and Loudon Wainwright III’s Grammy-winning tribute, High Wide & Handsome: The Charlie Poole Project, both accompanied by extensive liner notes.

The influence of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” is evident in subsequent music. It’s worth noting its likely inspiration on songs such as “Deal” by Garcia/Hunter of the Grateful Dead and Bob Dylan’s poignant “When the Deal Goes Down.”

Deconstructing the Song’s Enduring Appeal

What are the components that contribute to a song’s lasting power? Let’s dissect “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down,” examining its lyrics, melody, rhythm, and harmony (or chord structure).

The verses employ what are known as “floating lyrics,” verses that recur across various folk songs. Variations of the last three verses quoted above appear in numerous other folk tunes, including “He’s Gone Away,” “The Storms Are on the Ocean,” Woody Guthrie’s “Who’s Going to Shoe Your Pretty Little Feet,” “Hop High My Lula Gal,” and even traces can be found in the iconic ballad “John Henry.”

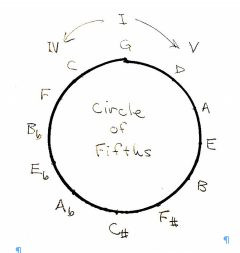

Circle of Fifths chart, illustrating the relationships between musical keys and chords, a concept central to the harmonic analysis of "Don't Let Your Deal Go Down".

Circle of Fifths chart, illustrating the relationships between musical keys and chords, a concept central to the harmonic analysis of "Don't Let Your Deal Go Down".

Charlie Poole’s rendition is characterized by an upbeat tempo and a lively, syncopated rhythm. However, the song has proven adaptable to diverse musical styles and tempos, showcasing its inherent versatility.

Structurally, the song follows a typical verse-chorus pattern, often described as A-B repetition, or sometimes variations like A-A-B or A-A-A-B. Each couplet within a verse shares essentially the same melodic phrase, and the chorus melody and chord progression closely mirror those of the verse, creating a sense of familiarity and ease of learning.

Poole’s melody is distinctive, marked by an almost immediate octave jump, for example, on the word “around” in the opening line and on the first and third iterations of “deal” in the chorus. (A similar melodic leap is found in the opening notes of “Little Maggie.”) Interestingly, many artists have successfully adapted less vocally demanding melodies while retaining Poole’s underlying chord structure, demonstrating the robustness of the harmonic foundation.

Given the fluidity of the verses and melody, the ambiguity of the chorus’s meaning, and a rhythm that isn’t particularly unique, what truly anchors this song and contributes to its enduring appeal? I argue that a significant factor is its compelling chord progression.

The Magic of Chord Changes

“Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” is built upon a four-chord progression that repeats twice in each verse and chorus. Using Roman numeral notation, this progression is: VI—II—V—I.

Poole, favoring the banjo-friendly key of G, played the chords as E-A-D-G. Transposed to the key of C, the progression becomes A-D-G-C.

Musicians familiar with music theory might recognize this as a circle of fifths (or circle of fourths) progression. To briefly explain, “I” (the “one” chord) represents the tonic, or the key of the song, which is G in Poole’s version. Moving to the fifth note of the G scale yields D, the “V” chord. The V chord of D is A, and the V of A is E. Continuing this sequence eventually leads back to G, completing a cycle through all twelve musical tones. This is the essence of the circle of fifths.

Because D is the V chord of G, G is conversely the IV chord of D. Therefore, traversing the same sequence in reverse order traces the circle of fourths. In a circle of fifths diagram, moving clockwise from a chord reaches its V chord, while moving counter-clockwise reaches its IV chord.

The chords most closely related to the tonic are the IV and V chords, based on the fourth and fifth notes of the main scale. These three chords (I, IV, V) form the backbone of countless folk songs. The “one-four-five” song structure is a testament to the fundamental nature of these chords in Western music.

From a musical and psychological perspective, the V chord creates a sense of tension that naturally resolves when followed by the I (tonic) chord. The V-I cadence is a common and satisfying resolution, used as the final two chords in countless songs to create a feeling of closure.

Now, let’s re-examine the progression in “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down”: E-A-D-G. Each transition within this sequence – E-A, A-D, and D-G – represents a V-I resolution. Instead of a single resolution at the end of a phrase, we experience three! This cascading series of resolutions contributes significantly to the song’s subconscious appeal. Furthermore, the progression begins with a G-E (I-VI) transition, which is more dramatic and less common in folk music, adding another layer of harmonic interest.

Echoes in Other Music

Interestingly, this chord progression is embedded within the more complex sequence used in Arlo Guthrie’s epic “Alice’s Restaurant,” suggesting its subtle yet pervasive influence. Perhaps that song, and others employing similar harmonic techniques, will be subjects for future explorations.

In the meantime, for those interested in learning to play “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down,” numerous resources are available online. Exploring different versions and interpretations is a rewarding way to further appreciate the enduring legacy of this classic folk song.