The expansion of the Western Canon to include a more diverse range of composers has brought previously unheard voices and works into the spotlight. Figures like Florence Price, whose compositions are now celebrated in concert halls globally, and Amy Beach, whose unpublished manuscript “Birth” was recently highlighted, exemplify this enriching rediscovery. This resurgence begs the question: what draws us to these unpublished musical treasures, and why were they initially kept from the public ear?

While researching the complete art song repertoire of Amy Beach for my dissertation in 2022, I encountered discrepancies in existing lists of her works. The inconsistencies stemmed from the inclusion, or exclusion, of unpublished songs. My quest to create a definitive corpus led me to the archives at The University of New Hampshire and the University of Missouri at Kansas City, repositories of Beach’s manuscripts and diaries. Among the wealth of unpublished material, two songs immediately captured my attention: “April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl.”

Manuscripts for “April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl.” Courtesy of University of New Hampshire Library.

Before delving into these lesser-known pieces, consider Amy Beach’s recognized style by listening to “Ah, Love, but a Day!” from her Three Browning Songs, beautifully performed by soprano Kate Royal and pianist Malcolm Martineau. Now, contrast this with MIDI recreations of “April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl.” The difference is striking. A palpable tension, dissonance, and angst emerge in the unpublished works, a departure from the Amy Beach’s familiar romanticism. Why this divergence?

Composed in close succession on June 11th and 13th, 1935, “April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl” appear to be conceived as a pair. The timing of their creation, almost exactly twenty-five years after the death of Beach’s husband, Dr. Henry Harris Aubrey Beach on June 28, 1910, offers a crucial insight. Dr. Beach’s passing was a profound personal and professional turning point for Amy. Beyond losing her life partner, she lost the figure who had significantly shaped her musical career. He had discouraged her from public performance as a pianist and influenced the direction of her compositions. She frequently set his poems to music, dedicated pieces to him, and their days often concluded with them performing her latest songs together.

Amy Beach at age 18 with her husband, Dr. H. H. A. Beach. Photograph by an unknown photographer, dated 12 Aug. 1886.

Amy Beach at age 18 with her husband, Dr. H. H. A. Beach. Photograph by an unknown photographer, dated 12 Aug. 1886.

The texts and musical language of “April Dreams” and “The Deep-Sea Pearl” offer a glimpse into Beach’s emotional landscape as she approached the 25th anniversary of her husband’s death. Both songs explore themes of longing and loss, where the desired object remains elusive. Musically, this yearning and conflict are conveyed through her choices in tonality and accompaniment. Let’s examine each song in detail. Consistent with her post-husband song composition, Beach selected poems written by women.

APRIL DREAMS

Katherine W. Harding’s poem, “April Dreams,” captures the ephemeral nature of dreams, fleeting upon waking and yearned for in their absence. The speaker desires their return, emphasizing their elusive quality. The second stanza personifies the wind, detailing its interaction with crocuses, symbols of spring and new beginnings, hinting at the potential return of dreams. However, the poem concludes with the acknowledgment that these dreams are distant, perhaps irrevocably lost.

My dreams have gone adventuring

Tip-toeing down the lea

I wish a little April wind

Would blow them back to me.

A little crocus kissing wind

All full of fluting song

And scent of drowsy, waking buds

That have been sleeping long.

O wind blow back the wanderers

Wherever they may be

My little dreams adventuring

So far away from me!

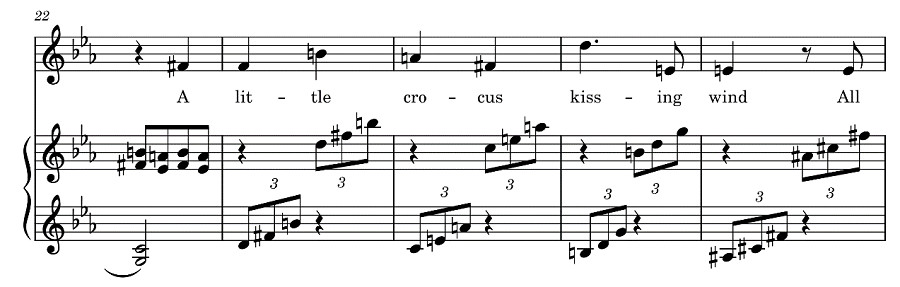

Musically, the piano introduction immediately establishes the dream’s intangible quality through tonal ambiguity. Rocking eighth notes in the right hand alternate between fourths and fifths (Eb-Ab, C-G). Individually, these intervals sound bare and unresolved; combined, they suggest an AbM7 or Cmadd6 chord, both dissonant and yearning for resolution. This rocking motif persists throughout the first stanza, underpinned by a descending bass line that begins and continues without resolution.

The second stanza offers a fleeting moment of hope, mirroring the poem’s imagery of spring and renewal. A new accompaniment pattern emerges – sweeping, ascending arpeggios. A hint of G Major tonality appears, yet it’s quickly overshadowed by chromaticism. Beneath this glimmer of hope, the descending bass line persists, a constant reminder of the dreams’ distance.

Musical example from “April Dreams” analysis showing piano score excerpts.

Musical example from “April Dreams” analysis showing piano score excerpts.

Both accompaniment patterns return in the final stanza, alongside a repeated line from the first: “the dreams adventuring.” This time, however, the line is set to the hopeful ascending triplet figure, creating an ironic juxtaposition against the narrator’s sense of distance from her dreams. The song concludes without tonal resolution, lacking a clear cadence or satisfying ending, mirroring the poem’s and perhaps Amy Beach’s own unresolved feelings regarding her loss.

THE DEEP-SEA PEARL

“The Deep-Sea Pearl,” while not explicitly about dreams, presents a more direct connection to the loss of Dr. Henry Beach. Edith M. Thomas’s poem centers on the pearl as a symbol – often hidden within oysters and associated with purity, wisdom, and feminine beauty. After establishing an unconventional love, the poem shifts to a darker tone: the pearl originates from the pain of a wound, representing the complex interplay of love and suffering. In the final verse, the narrator declares the pearl eternally sealed and inaccessible at the bottom of the Deep Sea, a treasure forever out of reach. Emotional conflict permeates the poem, reflecting the bittersweet nature of the relationship and its aftermath.

The love of my life came not

As love unto others is cast;

For mine was a secret wound —

But the wound grew a pearl, at last.

The divers may come and go,

The tides, they arise and fall;

The pearl in its shell lies sealed,

And the Deep Sea covers all.

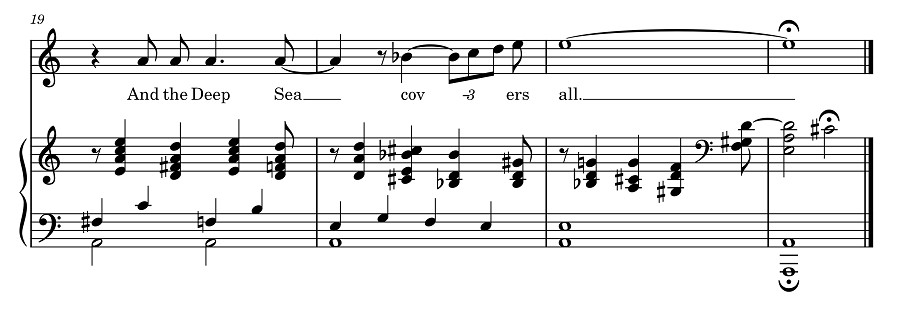

Opening in A minor, the song evokes the sonic imagery of the Deep Sea. Beach, like many composers before her, associated the minor mode with sadness, reserving it for pieces with particular emotional weight. Similar to “April Dreams,” a descending bass line in A minor persists throughout, representing the depths of the ocean. Syncopated block chords create a rhythmic texture reminiscent of ocean waves. When the pearl is mentioned in the text, a sustained C# in the piano’s left hand suggests A Major as a possible symbolic representation of the pearl.

The musical setting of the second stanza echoes the first, with the return of the descending bass line and syncopated block chords. However, the stanza’s conclusion masterfully captures the poem’s bittersweet essence. A pedal point on the tonic A is sustained as chromatic, dissonant chords descend into the final harmonies. Unlike “April Dreams,” this song offers a degree of resolution. A suspension over the pedal A resolves to a Picardy third, confirming the association of A Major with the pearl, a bright gem hidden within the murky minor depths of the Deep Sea.

Musical example from “The Deep-Sea Pearl” analysis showing piano score excerpts.

Musical example from “The Deep-Sea Pearl” analysis showing piano score excerpts.

Returning to the initial question of why Amy Beach chose not to publish these songs: while definitive answers remain elusive, their intensely personal nature seems evident. In her 1918 article, “To the Girl Who Wants to Compose,” Beach reflected on the profound connection between a composer and their work: “It may be not only the creation of an art-form, but a veritable autobiography, whether conscious or unconscious.” Beach’s songs, particularly these unpublished pieces, reveal a more intimate facet of her life than previously understood. With over 120 songs in her complete oeuvre, Amy Beach’s musical landscape, both published and unpublished, continues to offer rich ground for discovery and appreciation.

Notes

Mrs. H. H. A. Beach, “To the Girl Who Wants to Compose,” Etude 36/11 (November 1918): 695.

Adrienne Fried Block, Amy Beach: Passionate Victorian (NY: Oxford University Press, 1998).

Megan Lyons, “Unsung: A Corpus Study on the Art Songs of Amy Beach,” Ph.D. diss. (University of Connecticut, May 2022).

Great Performances, “The Lost Manuscripts of Composer Florence Price,” Season 49 (Episode 23).

Guest Blogger: Megan Lyons

Megan Lyons is currently an Assistant Professor of Music Theory at Furman University. Her research areas include music theory pedagogy, the songs of Amy Beach, and Joni Mitchell’s use of alternate guitar tunings. She has presented her research on Mitchell at national and international conferences, and currently serves as founder and co-chair of SMT-Pod.