Suzanne Vega’s “Tom’s Diner” song is more than just an earworm; it’s a cultural touchstone. This seemingly simple a cappella track, released in 1987 on her album Solitude Standing, unexpectedly became a global hit and even played a pivotal role in the development of the MP3 format. But the story of “Tom’s Diner” is as unassuming and captivating as the song itself, originating from a humble Upper West Side eatery and evolving into a multifaceted piece of music history.

The genesis of “Tom’s Diner” dates back to 1981, though it was written in the spring of 1982. Vega, then a student at Barnard College in Manhattan, frequented Tom’s Restaurant, a no-frills establishment located at 112th and Broadway. Even after graduating and entering the workforce, Tom’s remained a regular haunt. She describes it not as the charming, atmospheric diner some might imagine, particularly due to its later fame as the exterior of Monk’s Cafe in Seinfeld, but rather as a “plain, greasy place.” This very ordinariness, however, was part of its appeal for Vega.

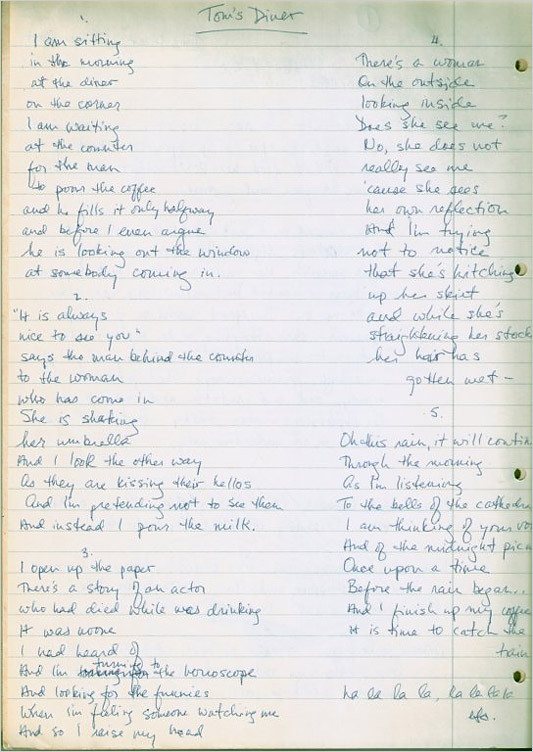

Handwritten lyrics to

Handwritten lyrics to

The inspiration for the song’s unique perspective came from a conversation with her photographer friend, Brian Rose. Rose, known for his photographs of the Lower East Side and the Berlin Wall, once described feeling as though he viewed the world “through a pane of glass.” This sense of detached observation, both romantic and alienated, resonated with Vega and became the core concept for “Tom’s Diner.” Drawing from her dramatic monologue classes at Barnard, she envisioned the song as a miniature film, where the narrator observes the surrounding scene without direct engagement, their reactions filtered through this pane of glass.

The lyrics are a series of vignettes, capturing mundane moments within the diner. The mention of an actor dying refers to William Holden, and fans have even commemorated the day after his death as “Tom’s Diner Day.” The detail about a woman “fixing her stockings” was a fictional addition, while the “midnight picnic” lyric stems from a real picnic Vega shared with songwriter Jack Hardy on the steps of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine.

The melody itself arrived spontaneously as Vega walked down Broadway. She envisioned a “jaunty” tune, something with a French film soundtrack vibe, perhaps reminiscent of a vaudevillian piano piece in a Truffaut film. She appreciated the near rhymes in the lyrics, like “diner” and “corner,” “sitting” and “waiting.” Although the actual establishment was named Tom’s Restaurant, she opted for “diner” as it simply “sings better.” Lacking piano skills herself and not knowing a pianist, Vega initially performed the song a cappella in her live shows, a decision that would profoundly shape its trajectory.

The immediate audience reaction to the a cappella rendition of “Tom’s Diner” was striking. Vega noticed that whenever she began singing, “I am sitting, in the morning…”, the audience would stop their conversations and turn their attention to the stage. Its captivating effect led her to consistently use it as her opening song. This success even translated to large venues, like the Prince’s Trust concert in 1986, where Vega opened for 10,000 people with just her voice and “Tom’s Diner,” and it worked its magic.

Naturally, recording the song a cappella for her second album, Solitude Standing, felt like a logical step, given its proven live appeal. The album version also included a reprise, which Vega hoped had a Brechtian feel. Solitude Standing, which also featured her hit single “Luka,” became a massive success, selling three million copies globally. Interestingly, the album’s pristine sonic quality led some audiophiles, including Philip Glass, to use it for testing sound systems.

However, it was the unexpected remix of “Tom’s Diner” by the British electronic duo DNA in 1990 that catapulted the song to another level of fame and relevance. Vega was touring for her follow-up album, Days of Open Hand, when her manager informed her about the unauthorized remix. Initially, there were considerations of legal action for copyright infringement.

Vega, however, decided to listen to the DNA remix before making any decisions. To her surprise, she enjoyed it. It wasn’t a parody, which had been a concern after the wave of parodies that followed “Luka.” Instead, DNA had taken the original a cappella vocal track and added a dance beat, creating something entirely new while preserving the essence of the original “Toms Diner Song”. Vega likened it to the Lemonheads’ cover of “Luka,” which she had also appreciated.

DNA, consisting of Nick Batt and Neal Slateford, had created vinyl copies of their remix, playfully titled “Oh Susanne!”, and sold them locally after, they claimed, failing to get a response from Vega’s record company for permission. The raw, somewhat lo-fi energy of the remix, born from imagination rather than expensive studio equipment, appealed to Vega. She arranged a meeting with DNA, initially picturing them as a different type of act based on the sound of the remix. She was surprised to meet two white men, not the group she had envisioned.

Instead of pursuing legal action, Vega and her manager struck a deal with DNA for a flat fee. A&M Records paid the fee, and Vega retained the rights. She made the crucial decision to credit the release as “Tom’s Diner, by DNA featuring Suzanne Vega,” wanting to acknowledge the remixers’ contribution and signal that it wasn’t her original production. Her concerns about audience acceptance proved unfounded; the remix was widely embraced, even crossing over to R&B radio stations.

The success of the remix, however, overshadowed the release of Days of Open Hand. While the remix revitalized “Tom’s Diner,” it didn’t translate into increased sales for her new album. The public’s appetite was firmly fixed on this reimagined version of a song from her back catalog. Despite the mixed reception of Days of Open Hand at the time, Vega learned a valuable lesson: raw creative energy and compelling ideas can sometimes resonate more powerfully than meticulous studio perfection.

The DNA remix unleashed a flood of reinterpretations of “Tom’s Diner” from around the globe. Vega received countless versions, from a reggae improvisation by Michigan & Smiley to Nikki D’s hip-hop take about teenage pregnancy. To manage this burgeoning collection, Vega, with engineer Denny McNerney, compiled “Tom’s Album” in 1991, featuring eleven different versions of the song. She even secured artwork from Tom Hart, who had been inspired by the original song. Releasing “Tom’s Album” involved navigating complex copyright permissions, requiring Vega to seek clearance from those who had initially sampled or remixed her work without authorization. Despite the administrative hurdles, “Tom’s Album” became a cult favorite, often mistaken for a bootleg. While plans for “Tom’s Album” volumes 2 and 3 remain unrealized due to the ongoing copyright complexities, the stream of “Tom’s Diner” remixes continues, with over 30 versions existing, including notable remixes by Danger Mouse and Tupac. Vega maintains a liberal approach to remix requests, approving almost every one, except for a request for pornographic use. She views these remixes as a testament to the song’s enduring appeal and a way to connect with a wider audience.

Beyond its remix history, “Tom’s Diner” has an even more unexpected technological legacy: its connection to the development of the MP3 format. In 2000, Vega was surprised to learn from a fellow parent that she was being called the “mother of the MP3.” An article in Business 2.0 titled “Ich Bin Ein Paradigm Shifter: The MP3 Format is a Product of Suzanne Vega’s Voice and This Man’s Ears” detailed the song’s unlikely role.

Karl-Heinz Brandenburg, a key developer of the MP3, used “Tom’s Diner” to refine his compression algorithm. He believed that the song’s warm, a cappella vocals would be particularly challenging to compress without distortion. Initially, the MP3 compression of “Tom’s Diner” sounded “monstrous,” filled with distortions. Brandenburg and his team spent months tweaking the algorithm, repeatedly testing it with “Tom’s Diner” until they achieved a clean compression. The article claimed that the resulting MP3 code, used to compress countless songs since, was fundamentally shaped by the way Brandenburg learned to compress Suzanne Vega’s voice.

Vega visited the Fraunhofer Institute in Erlangen, Germany, where she met Brandenburg and his team. During a press conference, they played her the original, distorted MP3 version of “Tom’s Diner,” followed by the refined, “clean” version. While the engineers asserted that the MP3 now perfectly replicated the original, Vega, with her trained ear, detected a slight difference, noting a touch more high-end and a slight loss of warmth in the MP3 version. The engineers, adhering to the “Black Box theory,” insisted on perfect replication. Despite this minor disagreement, Vega expressed pride in her song’s unintentional contribution to music technology.

From its humble origins in a simple diner to its global remix success and its surprising role in MP3 history, “Tom’s Diner” has had an extraordinary journey. It’s a testament to the power of simple observation, a catchy melody, and the unpredictable ways in which a song can resonate and evolve in the cultural landscape. Suzanne Vega’s “Tom’s Diner” song remains a fascinating case study in musical serendipity and lasting impact.