As a songwriter, the question of what makes a song truly resonate and last through generations is constantly on my mind. From the vast ocean of music ever created, why do certain songs continue to be sung and revisited decades, even centuries, later? It’s a fascinating puzzle. Let’s delve into the heart of some of these enduring melodies. Today, we’re focusing on a classic: “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down,” sometimes also referred to as a Going Down Down Song due to its memorable chorus. This piece, like many timeless folk tunes, boasts origins shrouded in the mists of time, with its earliest known recording dating back to 1925 by Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers.

This song has journeyed through time under various titles, including “The Deal,” “Deal Rag,” and others, embraced by a diverse range of artists across genres. Notable renditions exist from legends like Doc Watson, Flatt & Scruggs, the New Lost City Ramblers, David Bromberg, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and even an instrumental interpretation by Bob Wills. The beauty of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” lies in its adaptable nature. Its lyrical themes and structural flexibility have allowed singers to infuse it with a rich tapestry of lyrics, both traditional and newly crafted, ensuring its continued relevance.

Charlie Poole’s Breakthrough with “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues”

Charlie Poole’s 1925 recording, titled “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues,” marked his debut into the commercial music scene and became an instant hit. Selling over 100,000 copies in an era where record sales were significantly lower, it was a monumental success. Ironically, Poole’s compensation was based on songs recorded, not records sold, a common practice at the time that didn’t fully reward his breakthrough success. The verses of Poole’s version paint a picture of the itinerant musician’s life, intertwined with the ache of leaving a loved one behind. The recurring “deal” in the chorus is widely believed to be a reference to gambling, specifically card games. Online discussions reveal ongoing speculation about the exact card game alluded to, now lost to time.

Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Down to Memphis, Tennessee

Any old place I hang my hat

Looks like home to meNow I left my little girl crying

Standing in the door

Throwed her arms around my neck

Saying ‘Honey, don’t you go’Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Done most everything

I’ve played cards with the King and the Queen

Discard the ace and the ten

Chorus

Oh it’s don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Before my last gold dollar is gone

Now where did you get them high top shoes?

Dress you wear so fine?

Got my shoes from a railroad man

And my dress from a driver in the mineWho’s gonna shoe your pretty white feet?

Who’s gonna glove your hand?

Who’s gonna kiss your lily white cheeks?

Who’s gonna be your man?Now Papa may shoe my pretty white feet

Mama can glove my hand

She can kiss my lily white cheeks

‘Til you come back again

Charlie Poole

Charlie Poole

Image: A portrait of Charlie Poole, banjo player and early country music star, instrumental in popularizing “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down”.

Charlie Poole’s influence extends far beyond just this one song. He is often considered a pioneering figure, perhaps even the original “gangster” of hillbilly music, setting a precedent for the country music outlaws who followed. Living in the Piedmont region of Virginia during the interwar period, Poole’s life was multifaceted. Beyond leading his banjo-playing band, he worked in mills, played baseball, and was known to be involved in moonshining. He was consistently described as a hard-drinking and boisterous character. Despite a successful recording and performing career, his life was tragically cut short by alcohol abuse before the age of 40.

Poole’s legacy includes around 60 recorded songs, many of which have become enduring folk classics. Titles like “Sweet Sunny South,” “Only Old and in the Way,” “Hesitation Blues,” and “You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me” stand as testaments to his impact. These can be discovered online and in libraries, including the San Diego County Library, through excellent CD collections. Two notable compilations are You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me: Charlie Poole and the Roots of Country Music, featuring original recordings alongside modern interpretations, and Loudon Wainwright III’s Grammy-winning tribute, High Wide & Handsome: The Charlie Poole Project, both accompanied by extensive liner notes.

Beyond covers of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down,” the song’s influence is evident in compositions like “Deal” by Garcia/Hunter and Bob Dylan’s “When the Deal Goes Down,” showcasing its lasting impact on songwriting.

Deconstructing the Song: Melody, Rhythm, and Harmony

Let’s delve into the musical components that make up “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down”—the lyrics, melody, rhythm, and harmony, or chords. The concept of “floating lyrics” is relevant here; it refers to verses that recur across various folk songs. Variants of the last three verses quoted earlier can be found in numerous other songs, including “He’s Gone Away,” “The Storms Are on the Ocean,” “Who’s Going to Shoe Your Pretty Little Feet” (popularized by Woody Guthrie), “Hop High My Lula Gal,” and even echoes in the classic ballad “John Henry.”

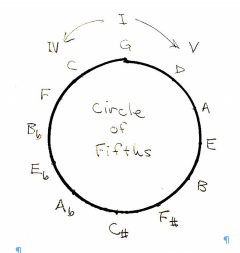

Circle of fifths chart

Circle of fifths chart

Image: A circle of fifths chart visually representing musical key relationships, relevant to understanding the chord progression of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down”.

Charlie Poole’s rendition of the song is characterized by an upbeat tempo and lively syncopation. However, its adaptability is clear, as other artists have successfully molded it to suit their own musical styles and preferences. Structurally, the song typically follows a verse-chorus pattern, often with an A-B repetition, or sometimes A-A-B or A-A-A-B variations. Each couplet within the verse shares essentially the same melody, and the chorus melody and chords closely mirror those of the verse, creating a cohesive and memorable musical structure.

Poole’s melody is particularly striking, featuring a nearly immediate octave jump, for example, on the word “around” in the first line and on the first and third iterations of “deal” in the chorus. (A similar melodic leap can be heard in the opening notes of “Little Maggie.”) While Poole’s melody is distinctive, others have adapted less vocally demanding melodies while retaining Poole’s underlying chord progression.

Given the fluid verses, adaptable melody, and somewhat generic rhythm, what truly solidifies “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” as an enduring song? The answer, I believe, lies significantly in its powerful chord progression.

The Magic of the Chord Progression

The song employs a repeating four-chord progression in both the verse and chorus, played twice through in each section. Expressed in Roman numeral notation, this progression is: VI—II—V—I. Poole typically played it in the key of G (a favored key for the five-string banjo), resulting in the chord sequence E-A-D-G. Transposed to the key of C, the chords would be A-D-G-C.

For those with musical experience, this progression will be recognizable as a circle of fifths (or circle of fourths) progression. To briefly elaborate: “I” (the “one” chord) represents the tonic, or key center of the song, which is G in Poole’s version. Moving to the fifth note of the G scale yields D, the “V” chord. The V chord of D is A, and the V of A is E. Continuing this sequence eventually leads back to G, completing the cycle through all 12 tones of Western music – the circle of fifths.

Because D is the V chord of G, G is conversely the IV chord of D. Therefore, reversing the sequence traces the circle of fourths. In a circle of fifths diagram, chords adjacent clockwise are V chords (D is V of G), and counter-clockwise neighbors are IV chords (C is IV of G). The chords most closely related to the tonic are the IV and V chords, built on the fourth and fifth scale degrees. These three chords (I, IV, V) form the backbone of countless folk songs, often referred to as “one-four-five” songs.

For complex acoustic and psychological reasons, the V chord creates a sense of tension that naturally resolves when followed by the I (tonic) chord. This V-I resolution is a cornerstone of musical harmony, used in countless songs to create a feeling of closure.

Now, examining the progression in “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down”: E-A-D-G. Each transition within this sequence embodies a V-I relationship (E-A, A-D, D-G are all V-I progressions). Instead of a single resolution at the end, we experience three! This layered resolution, coupled with the opening transition from G to E (I-VI), which is both dramatic and less common in folk music, contributes significantly to the song’s subconscious appeal.

“Going Down Down Song” and Beyond

Interestingly, this chord progression forms part of the more intricate sequence found in “Alice’s Restaurant,” among other songs, suggesting its wider influence. Perhaps that’s a topic for a future exploration. In the meantime, for those interested in learning to play, a video demonstration of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” in the key of E on guitar is available https://youtu.be/pd13-5in7jc. Feel free to sing along and experience the enduring charm of this timeless tune for yourself.