The magic of Disney’s Beauty and the Beast resonates far beyond its captivating storyline and characters; a significant part of its charm lies in its unforgettable music. Recently, after revisiting the 2017 live-action adaptation of Beauty and the Beast, I found myself, as a devoted music enthusiast, drawn into a deeper exploration of its iconic theme song. The more I analyzed it, the more profound my appreciation became for its intricate composition.

Alan Menken’s musical style, often described as accessibly diatonic and repetitive, might initially seem straightforward. However, beneath this apparent simplicity lies a sophisticated understanding of Classical music principles. What elevates “Beauty and the Beast,” the song, beyond typical popular music is the depth of its musical construction. Let’s delve into the elements that make this soundtrack masterpiece truly exceptional.

Deconstructing the Magic: Analyzing “Beauty and the Beast” Songs

To truly appreciate the artistry within “Beauty and the Beast” songs, a valuable approach is to pinpoint the most impactful moments and dissect how the composer meticulously builds towards these peaks.

Consider the 1991 animated film arrangement of the titular song. For many listeners, a particularly striking moment emerges during the transition from the bridge to the second verse, specifically highlighting the poignant lyric, “as the sun will rise.”

This moment’s power stems from Menken’s ingenious reimagining of familiar American song clichés, skillfully prepared through motivic development. These techniques, as we will discover, are deeply rooted in the traditions of Classical music, lending a timeless quality to these beloved Beauty And The Beast Songs.

Reimagining Musical Clichés

The “sun will rise” segment artfully employs two well-known musical clichés: the deceptive cadence and the bVI-bVII-I progression. Individually, these are common musical gestures.

However, Menken’s genius lies in his innovative approach. He doesn’t present these clichés in isolation; instead, he masterfully fuses them, along with a modulation, into a cohesive and impactful musical statement within these beauty and the beast songs.

But how exactly does Menken achieve this seamless integration?

Let’s begin by examining the modulation that occurs between the bridge (“Ever just the same…”) and the subsequent second verse (“Tale as old as time…”).

To provide context, let’s first consider a simplified version of this transition, stripping away the deceptive cadence, the bVI-bVII-I cadence, and the modulation itself.

To this stripped-down example, let’s reintroduce the deceptive cadence. Menken concludes the bridge with a transposed deceptive cadence. Crucially, this cadence alone does not necessitate a modulation. He could have easily remained in D-flat major, utilizing the chord progression that underpins the phrase “…least, Both a little scared”:

Now, imagine Menken desired both the deceptive cadence and a step-up modulation, but without resorting to the bVI-bVII-I progression. By employing C-flat as a conventional pivot chord—a chord shared between two keys, in this case D-flat and E-flat—the modulation might sound like this:

In this third, yet less compelling variation, Menken employs C-flat as a pivot chord. However, the true brilliance of Menken’s version lies in how he utilizes the bVI-bVII-I progression, enriching the pivot C-flat chord with remarkable depth and emotional resonance within these beauty and the beast songs. To understand this nuance, let’s briefly define some key musical terms.

Cadential Subterfuge: A Clever Trick

A typical cadence, such as V-I (e.g., G-C), comprises two chords: the “leading chord” and the “resting chord.” Often, a “preparing chord” precedes these two, creating a progression like IV-V-I (e.g., F-G-C).

In my third re-composed example, C-flat functions unambiguously as a “resting” chord. While it bridges D-flat to E-flat in the following bar, it doesn’t act as a “preparing,” “leading,” or “resting” chord within the subsequent cadence.

However, in Menken’s rendition of these beauty and the beast songs, the cadential function of C-flat is deliberately ambiguous. Drawing inspiration from Chopin’s compositional techniques, Menken ingeniously reinterprets what we initially perceive as a “resting” chord into a “preparing” chord. This clever maneuver creates a kind of aural “whiplash,” as our perception of the chord’s function is instantly reversed.

Consider Chopin’s Fourth Ballade, where he masterfully employs this technique. From the second to third system, Chopin clearly cadences from a “leading” F7 chord to a “resting” B-flat minor chord, establishing B-flat minor as the temporary key. However, Chopin immediately redefines this B-flat minor chord as a “preparing” chord to modulate back to the Ballade’s home key of F minor.

Listen now to how Menken utilizes a similar strategy in “Beauty and the Beast”:

Similar to Chopin, Menken cadences from a “leading” B-flat chord to a “resting” C-flat chord, seemingly resolving into E-flat minor. Yet, he immediately reinterprets the C-flat chord as a “preparing” chord in the bVI-bVII-I progression to modulate to E-flat major. This C-flat “preparing” chord is followed by a D-flat “leading” chord, and finally, the E-flat “resting” chord, completing the ingenious harmonic shift in these beauty and the beast songs.

Menken essentially declares, “Why simply extend the phrase to solidify E-flat major, as you did, Chopin, when I can confirm the key change and switch to major mode simultaneously?”

Menken’s voice leading in the cello line, starting at “sure,” is particularly masterful in reinforcing this harmonic telescoping. Beginning on B-flat (D-flat’s submediant degree) before the word “(be-)fore,” the cellos descend stepwise over five notes until reaching E-flat, the new tonic.

This stepwise descent to the tonic reinforces the “whiplash” modulation, making it feel inevitable. Scales descending from dominant to tonic are deeply ingrained in Western musical understanding, representing closure. This familiar sonic gesture subtly softens the striking nature of the E-flat arrival, adding a layer of expected resolution to the surprise.

The Power of Motives: Building Musical Structure

The potency of this modulation isn’t solely derived from Menken’s clever manipulation of clichés. In fact, he meticulously prepares the listener for this moment from the song’s outset through the strategic use of structural melodic motives within these beauty and the beast songs.

A motive is a concise melodic or rhythmic idea that recurs and evolves throughout a composition. Motives are prevalent across Western music—pop, Classical, jazz, soundtracks—but often function as surface embellishments.

Employing motives in this surface manner is akin to constructing a sculpture from Lego blocks:

Dragon Lego Sculpture

Dragon Lego Sculpture

While we recognize the dragon, we also readily perceive the individual blocks, distinct in their profiles and presented sequentially on the surface.

A prime example of such a surface motive in “Beauty and the Beast” is the rhythmic pattern: four eighth notes followed by a longer note. The vocal melody itself is largely constructed from this motive, though performers like Angela Lansbury and Emma Thompson imbue it with expressive rubato.

Most Western music leverages this overt surface connection to create coherence and a framework for contrast. However, what distinguishes Classical music, particularly Germanic Classical music, is the structural application of motives.

This isn’t an either/or distinction. Many structural motives also appear on the surface. But structural motives extend beyond surface details, influencing: (a) the shaping of entire note groups, (b) phrase beginnings and endings, and (c) even the underlying harmony, rather than merely existing atop it.

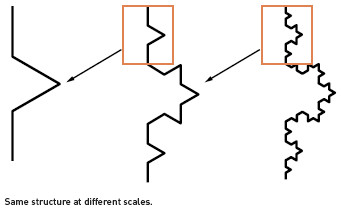

Structural motivic use is more akin to creating fractals:

Fractal Image

Fractal Image

As the design becomes more intricate, the repeating pattern at different scales becomes less immediately apparent.

The coastline of England serves as a real-world example of a more subtle fractal, where the repeating pattern is less visually obvious. This subtlety is heightened when the motivic pattern is not the only musical element present. Brahms, for instance, employs the C#-D-C# motive structurally in his Op. 118, No. 2 Intermezzo. Yet, most listeners might not consciously detect it, even as it shapes the piece’s larger structure, contributing to its profoundly affecting character.

Motives in “Beauty and the Beast” Songs: A Closer Look

Like Brahms, though perhaps less intensely, Menken imbues the ascending minor second interval with structural significance, prominently featuring it throughout these beauty and the beast songs.

This interval initiates the “Beauty and the Beast” motive that opens the song, first in the flutes and then the violins. As part of this motive, it also concludes both verses. More subtly, the interval underpins the inner voice leading in the introduction—F to G-flat in bars 1-2—and in the singer’s entrance at each verse—F to G-flat from “Tale” to “time” and “Just” to “change.” Beyond its melodic prominence, Menken also highlights F to G-flat in the bass line during the bridge, as the harmony oscillates between the mediant and subdominant (F and G-flat).

To emphasize these repetitions, imagine a clarinet playing them over the original music.

You’ll observe that Menken often layers multiple iterations of the motive simultaneously. This density and variety of repetition constitute the preparation for the modulation. He subtly trains your ear to recognize the motive, even unconsciously.

However, Menken withholds a crucial variation: transposition. The motive has not yet been presented in a different key.

Therefore, when the motive appears as B-flat to C-flat in the deceptive cadence, it commands attention. Listen again to the clarinet-enhanced version, focusing on the highlighted B-flat to C-flat motion.

Having captured your attention with this deceptive cadence, Menken amplifies the surprise element through the “cadential whiplash” from bridge to verse, as previously explained, in these beauty and the beast songs.

This “cadential whiplash” is effective precisely because the deceptive cadence sets the stage. Without it, Menken could still employ the bVI-bVII-I progression, but the effect would lack the motivic connection and would modulate down to C major, resulting in a net decrease in tension.

In essence, the ascending minor second motive is crucial to this passage’s impact, establishing the deceptive cadence. Furthermore, the descending cello line, previously mentioned, also contributes motivically. It transposes the vocal line’s pitches from “Ever as before” (a melodic motive first heard in “Then somebody bends”) up a diatonic step.

As we hear these descending stepwise pitches in the cello, our minds anticipate the pattern’s completion, not only due to our understanding of scales but also because this specific scale fragment holds meaning within the song’s motivic framework.

In conclusion, Menken masterfully employs two distinct motivic ideas to guide us towards and underscore the “as the sun will rise” moment in these beauty and the beast songs. Just as his “cadential whiplash” echoes Chopin, this motivic development draws from the rich tradition of Classical music.

The presence of these Classical elements should not be unexpected. “Beauty and the Beast” was composed by Alan Menken, a musician deeply familiar with Classical music, known for improvising in the styles of Bach and Beethoven and holding a musicology degree from NYU. While Classical techniques are not prerequisites for musical depth, “Beauty and the Beast” demonstrates how they can enrich simplicity, creating music that is both accessible and profoundly moving in these timeless beauty and the beast songs.