Jerry Jeff Walker, a figure synonymous with the soul of Austin, Texas, passed away on October 23 at the age of seventy-eight, after a three-year battle with throat cancer. While he became the embodiment of the Austin music scene, it might surprise some to learn that this quintessential Texan troubadour was originally a New Yorker, cutting his teeth as a singer-songwriter in the vibrant Greenwich Village of the mid-1960s. His relocation to Austin in the early seventies marked a pivotal moment, as he became a central figure in the burgeoning outlaw country movement. This genre, a haven for artists deemed too unconventional for mainstream country radio, boasted luminaries like Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson, Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, and Steve Earle. These musicians, deeply enamored with Texas, crafted a sound that resonated with the spirit of the land, a sound that felt intrinsically Texan. Like Austin itself, a liberal enclave within Texas, they were mavericks, free-spirited individuals with roots in the hippie counterculture. Townes Van Zandt, the group’s tragic figure, succumbed to addiction at the young age of fifty-two. Walker’s presence is even captured in James Szalapski’s endearing 1981 documentary, Heartworn Highways, which offers a glimpse into the Austin outlaw scene.

My own journey with Jerry Jeff Walker’s music began nearly fifty years ago. At twenty-two, I found myself in Toronto, working temporary jobs while navigating the uncertain path towards a career in movie and theatre criticism. As a Montreal native who had studied in Boston, I felt adrift in Toronto, grappling with a sense of loneliness despite the support of friends and family. Among those who offered solace was my high school best friend, a professional musician playing guitar and singing in a downtown bar. He and his girlfriend would occasionally coax me out to clubs, introducing me to performers largely unknown to me – Jerry Jeff Walker being the most unforgettable. In 1973, like many, my awareness of Walker was limited to his authorship of “Mr. Bojangles,” a song I knew through his definitive rendition. Unbeknownst to me, he was on the cusp of releasing his sixth solo album, the seminal Viva Terlingua! (His musical journey prior to his solo career included two albums with Circus Maximus, a band he co-founded with Bob Bruno).

That particular night, Walker performed two sets. After the first, the venue thinned out, and we moved closer, finding ourselves just fifteen feet from the stage. The majority of his setlist drew from Viva Terlingua! and his preceding self-titled album. However, one song that remains etched in my memory was a poignant piece penned by Canadian singer-songwriter David Wiffen. Titled “More Often Than Not,” it narrates the tale of a weary, alcoholic, and creatively stagnant folk musician. Walker’s interpretation was profoundly moving, one of the most heartrending live performances I had ever witnessed. (This rendition can be found on the now-rare 1970 release, Bein’ Free.) The very next day, I acquired Jerry Jeff Walker, and throughout the remainder of the decade, I eagerly anticipated each new Walker album, which he released at an impressive pace of roughly one per year. I had the pleasure of seeing him in concert several more times in different cities. While always a captivating performer, none of these subsequent experiences quite matched the emotional resonance of that initial encounter, when I was a young man wrestling with solitude, and his gentle, whiskey-soaked voice reached out to me.

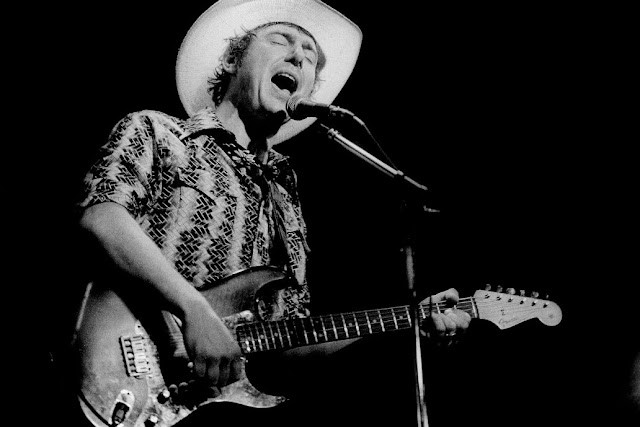

Jerry Jeff Walker performing live, showcasing his captivating stage presence and connection with the audience.

Walker’s personality – life-affirming, hard-drinking, irreverent, and anti-establishment – bursts forth from his recordings with exuberant energy. Listening to tracks like “Hill Country Rain” or “Gettin’ By,” or humorous, insider-laced novelty songs such as “Pissin’ in the Wind” and “Will There Be Any” (the unspoken, and rather cheeky, noun being “chickenshit,” a nuance often revealed in his live introductions), you quickly discern the singer as a free-spirited, “damn braces, bless relaxes” kind of character. His early albums feature songs that playfully mock record labels (he would later establish his own independent label in 1986) and those club patrons who, as he wryly observes in “Hairy Ass Hillbillies,” expect artists to perform every song in their repertoire. I recall hearing him respond to an insistent request for “Mr. Bojangles” that first night by famously telling the requester to “go f*** himself.” While not typically abrasive with his audiences, he immediately apologized, attempting to articulate the weariness a musician feels when constantly obligated to perform their sole commercially successful song. He favored a relaxed atmosphere; the rambling, jovial, seemingly improvised tune “Contrary to Ordinary” from his 1978 album of the same name feels like such a perfect self-portrait that it’s surprising to discover it was penned by Billy Jim Baker. In reality, he was an exceptionally affable performer; listening to his music feels like being invited to an intimate gathering with him and his close circle of friends.

While many songwriters draw from personal experiences, the tone of some of Walker’s songs, coupled with his casual delivery, creates an intimacy akin to late-night, alcohol-fueled confessions. Songs like “I Love You” and the tender ballad “Derby Day,” or “David and Me,” his poignant tribute to fellow musician David Bromberg, and the unforgettable “Stoney,” which recounts hitchhiking and busking across the country with a gospel-singing, concertina-playing companion he encountered in a Richmond, Virginia bar, paint vivid pictures of personal connection and shared experience.

For me, the Jerry Jeff Walker Songs that resonate most deeply are the melancholic ones. He possessed the remarkable ability to wrap his warm, gravelly voice around a sorrowful lyric like a comforting scarf. He was a master of the elegy, whether performing his own ballads (“When I Had You,” “Wheel,” “My Old Man,” “Leavin’ Texas,” co-written with Dave Roberts) or interpreting the works of other songwriters, many of whom, like Guy Clark and Gary P. Nunn, were close friends and collaborators. Among the early Walker albums I collected, Clark’s songs, alongside Walker’s own compositions, remain my favorites: the piercingly evocative “That Old Time Feeling,” “L.A. Freeway,” and the devastating “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” which recounts a boy’s bond with an aging, former oil driller who passes away in the final verse. Nunn contributed “Well of the Blues” and (with Karen Brooks) “Couldn’t Do Nothin’ Right,” which captures the waning days of a relationship. “Some Day I’ll Get Out of These Bars,” penned by Keith Sykes and Richard Gardner, is a heart-wrenching lament that draws a parallel between a desperate bar singer and a recently released convict who listens to his performances while drinking: “We’re a lot alike, guitar man, you and I / But your sentence is way too long.” “Eastern Avenue River Railway Blues” (Mike Reid) explores a different kind of yearning for escape, that of a young man trapped in the confines of the city. In “Tryin’ to Hold the Wind Up with a Sail” (Pat Garvey), the singer is awakened by his wife or lover, who is haunted by a nightmare and inconsolable in her distress. Walker’s rendition is exceptional; his unexpected syncopation of the second chorus lends it an ethereal, floating quality – you can almost hear the woman’s elusive nature, the singer’s struggle to ground her, mirroring the song’s evocative title.

Perhaps the Jerry Jeff Walker song that moves me most profoundly is “Stoney,” particularly the penultimate verse:

We split the road at Norwood

And he just shook my hand.

He said, “I’ll see you someplace, friend,”

But you know, he never has.

But we were that free then,

Just walkin’ down the road,

Never really carin’

Where that highway goes.

For years, I wondered if Walker ever reconnected with Stoney. It was much later that I discovered he was H.R. Stoneback, who transitioned from a nomadic life to become a poet and academic. But within Walker’s song, Stoney transcends his individual identity, becoming a symbol of youthful restlessness and adventurous spirit, a spirit that inevitably fades with time. Some carry the ache of this loss throughout their lives, while others channel it into creative expression.

Steve Vineberg, the author reflecting on the enduring legacy of Jerry Jeff Walker’s songwriting.