In the rich tapestry of Latin American folklore, particularly within Spanish-speaking communities in the United States and deeply rooted in Mexico, no ghost story resonates as profoundly as the legend of La Llorona. “La Llorona,” translating directly to “the weeping woman,” immediately conjures the central, haunting characteristic shared across all iterations of her tale: a mournful weeping that echoes through the night. Beyond this singular, defining trait, the spectral figure of La Llorona morphs and shifts dramatically. Stories diverge widely on her appearance, her actions, and the tragic origins that condemned her to wander as a spirit consumed by sorrow.

Exploring news accounts and the vast expanse of the internet reveals a kaleidoscope of La Llorona narratives. For a deeper dive, Edward Garcia Kraul and Judith Beatty’s book, The Weeping Woman: Encounters with La Llorona, offers a rich collection of these encounters. Delving into these stories, one encounters a multitude of variations. In some, La Llorona is a distant figure, spotted from afar, her presence alone instilling terror and triggering frantic flights home. In others, she is mounted on horseback, a spectral rider of the night. Still other tales depict her materializing unexpectedly in horse-drawn wagons or modern cars, delivering cryptic warnings against misbehavior before vanishing as abruptly as she appeared, reminiscent of the classic vanishing hitchhiker trope. In the most chilling accounts, an encounter with La Llorona proves fatal, marking a brush with death itself.

La Llorona’s legend is intricately interwoven with themes of children. In numerous versions, her weeping is attributed to the loss or death of her own children. These narratives often tragically depict her as the murderer of her offspring in life, her eternal punishment being an unending spectral search for them. Conversely, some stories portray her as appearing specifically to mothers, a somber figure in their lives, while others paint her as a child-snatcher, her presence heralding the permanent disappearance of children into the unknown.

The American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress, among other Library collections, safeguards unique versions of the La Llorona story. A particularly insightful resource is Bess Lomax Hawes’s seminal paper, “La Llorona in Juvenile Hall.” This work meticulously documents and analyzes La Llorona stories as they circulated within a California juvenile detention center during the 1960s. The published version of this paper is accessible online through the Bess Lomax Hawes collection at the Library of Congress, alongside an early draft within the Alan Lomax collection.

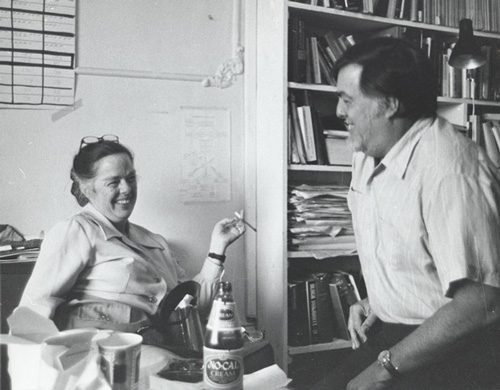

Bess Lomax Hawes and Alan Lomax sitting, laughing

Bess Lomax Hawes and Alan Lomax sitting, laughing

Hawes’s research provides a multifaceted perspective on La Llorona, encompassing the narratives of young women in detention, her scholarly review of existing interpretations, and her own insightful analysis. In her essay, Hawes meticulously details the diverse manifestations, both literal and symbolic, of La Llorona:

La Llorona typically appears as a malevolent spirit, either a harbinger or a direct cause of misfortune to the living. Sometimes she takes the form of a “dangerous siren,” tempting a solitary male late at night by confronting him as a pitiful, woebegone figure hidden under a rebozo. When offered assistance, she turns on the solicitous gentleman the face of a skeleton or a wild metallic horse’s head or no face at all. Sometimes she is observed simply roaming about at a distance, or most typically, she is heard weeping and shrieking through the night. A chance meeting with her is dangerous.

Hawes’s paper also includes direct transcripts of stories recounted by children in juvenile detention, offering a raw and unfiltered glimpse into their understanding of the legend. One typical account describes:

La Llorona has long hair and walks around crying. I heard from the counselors at Juvie that she had two kids that she drowned because they were bad. She drowned them in Tijuana. She attacks bad kids in Juvie. They say it is true.

Another, even more gruesome, version adds chilling specifics:

It is a woman who wasn’t quite all there who killed her three girls, 13 to 17 years old. She didn’t want them because something had happened to her husband, and they reminded her of him, so she drowned them. Their bones are buried in her back. She doesn’t know they are dead. She wears a long black cape with a peaked hood and goes around institutions and foster homes looking for her kids. If she sees a girl who looks like one of her daughters, she tries to cut out that feature. She comes around three days after it rains.

Stories like these, compiled by Hawes, often serve as descriptive fragments rather than complete narratives. They detail La Llorona’s typical actions and appearance, often with brief origin snippets. Another such influential text, readily available online via the Library of Congress, deserves mention for its vivid descriptions and impact. Published by Thomas Allibone Janvier in Harper’s Magazine in 1906, and subsequently reprinted in numerous newspapers, including the Washington, D.C. Evening Star, Janvier’s account provides a rich, albeit somewhat embellished, portrayal.

Image of a crying woman and three babies carved into a tree, with the inscription

Image of a crying woman and three babies carved into a tree, with the inscription

Janvier’s 1906 depiction paints a dramatic picture:

AS IS generally known, Señor, many bad things are met with by night in the streets of the City; but this Wailing Woman, La Llorona, is the very worst of them all. She is worse by far than the vaca de lumbre–that at midnight comes forth from the potrero of San Pablo and goes galloping through the streets like a blazing whirlwind, breathing forth from her nostrils smoke and sparks and flames: because the Fiery Cow, Señor, while a dangerous animal to look at, really does no harm whatever–and La Llorona is as harmful as she can be!

Seeing her walking quietly along the quiet street–at the times when she is not running, and shrieking for her lost children–she seems a respectable person, only odd looking because of her white petticoat and the white reboso with which her head is covered, and anybody might speak to her. But whoever does speak to her, in that very same moment dies!

The beginning of her was so long ago that no one knows when was the beginning of her; nor does any one know anything about her at all. But it is known certainly that at the beginning of her, when she was a living woman, she committed bad sins. As soon as ever a child was born to her she would throw it into one of the canals which surround the City, and so would drown it; and she had a great many children, and this practice in regard to them she continued for a long time. At last her conscience began to prick her about what she did with her children; but whether it was that the priest spoke to her, or that some of the saints cautioned her in the matter, no one knows. But it is certain that because of her sinnings she began to go through the streets in the darkness weeping and wailing. And presently it was said that from night till morning there was a wailing woman in the streets; and to see her, being in terror of her, many people went forth at midnight; but none did see her, because she could be seen only when the street was deserted and she was alone.

Sometimes she would come to a sleeping watchman, and would waken him by asking: “What time is it?” And he would see a woman clad in white standing beside him with her reboso drawn over her face. And he would answer: “It is twelve hours of the night.” And she would say: “At twelve hours of this day I must be in Guadalajara!”–or it might be in San Luis Potosí, or in some other far-distant city–and, so speaking, she would shriek bitterly: “Where shall I find my children?”–and would vanish instantly and utterly away. And the watchman would feel as though all his senses had gone from him, and would become as a dead man. This happened many times to many watchmen, who made report of it to their officers; but their officers would not believe what they told. But it happened, on a night, that an officer of the watch was passing by the lonely street beside the church of Santa Anita. And there he met with a woman wearing a white reboso and a white petticoat; and to her he began to make love. He urged her, saying: “Throw off your reboso that I may see your pretty face!” And suddenly she uncovered her face–and what he beheld was a bare grinning skull set fast to the bare bones of a skeleton! And while he looked at her, being in horror, there came from her fleshless jaws an icy breath; and the iciness of it froze the very heart’s blood in him, and he fell to the earth heavily in a deathly swoon. When his senses came back to him he was greatly troubled. In fear he returned to the Diputacion, and there told what had befallen him. And in a little while his life forsook him and he died.

What is most wonderful about this Wailing Woman, Señor, is that she is seen in the same moment by different people in places widely apart: one seeing her hurrying across the atrium of the Cathedral; another beside the Arcos de San Cosme; and yet another near the Salto del Agua, over by the prison of Belen. More than that, in one single night she will be seen in Monterey and in Oaxaca and in Acapulco–the whole width and length of the land apart–and whoever speaks with her in those far cities, as here in Mexico, immediately dies in fright. Also, she is seen at times in the country. Once some travellers coming along a lonely road met with her, and asked: “Where go you on this lonely road?” And for answer she cried: “Where shall I find my children?” and, shrieking, disappeared. And one of the travellers went mad. Being come here to the City they told what they had seen; and were told that this same Wailing Woman had maddened or killed many people here also.

Because the Wailing Woman is so generally known, Señor, and so greatly feared, few people now stop her when they meet with her to speak with her–therefore few now die of her, and that is fortunate. But her loud keen wailings, and the sound of her running feet, are heard often; and especially in nights of storm. I myself, Señor, have heard the running of her feet and her wailings; but I never have seen her. God forbid that I ever shall!

Janvier’s stories, originally published in Harper’s Magazine, were later compiled into Legends of the City of Mexico in 1910, complete with notes and references. He credits Gilberto Cano, a Mexico City native and fellow enthusiast of Mexican history and folklore, as the source of the tale above.

Beyond these descriptive accounts that hint at origins, richer, more developed narratives of La Llorona’s life, death, and spectral return are widespread. These longer versions thrive in oral tradition and frequently appear in children’s literature and shorter novels. Notable examples include Rudolfo A. Anaya’s novel The Legend of La Llorona, Joe Hayes’s children’s book La Llorona: The Weeping Woman, and Anaya’s children’s book La Llorona: The Crying Woman.

One such version, shared by a friend of the American Folklife Center, presents a poignant origin story:

A long, long time ago there lived a woman named Maria. She was the most beautiful woman in all of Mexico, muy hermosa, and she herself knew it too. Day after day, male suitors begged her for her hand in romance, but day after day men returned home defeated, con el corazón roto. This was the livelihood of Maria until a dashing young gentleman galloped into town and turned Maria’s life upside down; ella se volvió loca. She knew in an instant that she had to have him, for he was the only man to match her in beauty and in elegance. Soon they were to be wed, and not long after had two delightful chiquititos. This delight however was short lived, for one damning day the dashing gentleman became grotesque as he rode into town with another woman at his side. He rode up to Maria and pledged his life to this new woman whom he barely met, because his current wife was no longer beautiful. Maria’s heart burst into tiny shards of glass, invisible to the eye but painful for those handling it. That night, in a fit of sorrow and anger Maria decided to inflict the same agony toward the man that bestowed it upon her. Maria woke her two boys up, took their hands, and guided them to the river “for a bath.” Hand in hand, the three figures immersed themselves in the water…but under their mother’s hand, the little niños never came up for air. After the blood red glare of fury faded from sight, Maria realized what she had done. She shrieked from the gallows of her soul, “Mis Niños!” before letting the river water fill up her lungs. It is said now, this weeping woman or La Llorona has returned from the hereafter, searching for new children to claim as her own for all eternity.

Portrait photo of young woman

Portrait photo of young woman

This particular version is deeply ingrained in the memory of Camille Acosta, a former intern at the American Folklife Center. Growing up, Camille heard La Llorona stories from various family members, and this narrative resonated most strongly. Her fascination led her to delve deeper, culminating in her master’s thesis in Folklore at Western Kentucky University, where she collected and analyzed La Llorona stories from her family and community, presenting them with insightful interpretations. Her thesis offers a valuable perspective on the enduring legend.

As someone outside of Hispanic and Indigenous heritage, interpretation of La Llorona’s profound cultural significance is best left to voices within those communities. However, it is important to note the timeliness of this exploration. While National Hispanic Heritage Month has just concluded, the season of Halloween and Día de Muertos, deeply intertwined with themes of the supernatural and remembrance, is upon us. This exploration of La Llorona serves as a prelude to a series examining La Llorona stories and the La Llorona Song tradition in the lead-up to Día de Muertos. This series will culminate in a Folklife Today podcast episode featuring Camille Acosta, AFC reference specialist Allina Migoni, and folklorist and musician Juan Díes, promising a rich discussion of this iconic figure. These upcoming blogs will shed light on both well-known and lesser-known versions of the legend, alongside the scholarly works that have explored its depths.

So, who is La Llorona? In Camille Acosta’s words, she represents “the first concept of fear many of us [Mexican Americans] have ever experienced; she is our anxieties’ origin story.”

Camille further observes the deeply personal and subjective nature of La Llorona’s interpretation:

No two individuals view La Llorona in the same way. For example, the children I interviewed mostly saw La Llorona as a ghostly apparition more than willing to instill fear in young ones who misbehave. For the young adults including myself, there was description of La Llorona not just as a ghost but as a monster making us feel isolated from normalcy. For my parents however, La Llorona wavered from being a mother with the world on her shoulders to a key for escaping the harsh realities of life through ostension. Every single informant viewed the Llorona as a unique and personalized character in their own minds.

Ultimately, Camille emphasizes the empowering aspect of La Llorona’s enduring presence:

La Llorona is not only a reflection of our innermost fears, but she is the living breathing proof that we can overcome them as well. Her narrative passed down for centuries is a reminder that our voices are being listened to and acknowledged, La Llorona is understood more and more each and every day. And in a way, so are we.

Explore Camille’s insightful thesis for a deeper understanding of La Llorona, and stay tuned to Folklife Today for more on the legend, including the haunting melodies and cultural significance of la llorona songs.