The Rocky Horror Picture Show (RHPS) has cemented its place in cinematic history, not just for its visual spectacle and boundary-pushing themes, but also for its unforgettable soundtrack. Born from the creative minds of Richard O’Brien and Richard Hartley, the rhps songs are more than just musical numbers; they are the heart and soul of this cult phenomenon. This article delves into the origins and evolution of these iconic tracks, drawing from the creators’ own insights to understand how these rhps songs came to life and captured the imaginations of generations.

Richard O’Brien, the writer and actor behind the brilliance, envisioned a musical that resonated with his eternal adolescent spirit. Having been immersed in productions like Jesus Christ Superstar and Hair, O’Brien yearned for a show that celebrated his love for B-movies, rock’n’roll, and glam rock. This vision began to materialize when Jim Sharman, director of Jesus Christ Superstar, invited O’Brien to audition for a play at London’s Royal Court Theatre. It was there he connected with Richard Hartley, the composer for the play’s incidental music.

A pivotal evening saw Sharman visit O’Brien, where O’Brien shared early versions of what would become signature rhps songs, including “Science Fiction/Double Feature” and “Hot Patootie”. Sharman immediately recognized the potential, proposing a project at the Royal Court with the caveat of having “three weeks’ fun upstairs afterwards.” This playful proposition ignited the creation of more rhps songs and initial dialogue, a humble beginning that O’Brien himself didn’t foresee as a hit, expecting merely a brief, enjoyable run.

The evolution of the rhps songs was organic and dynamic, significantly shaped by rehearsals. “Science Fiction/Double Feature,” initially conceived independently, contained the suggestive line, “See androids fighting Brad and Janet.” These names, embodying a quintessential wholesome couple, inspired the need for their own introduction, leading to the birth of “Dammit Janet.” O’Brien reflects on the relatable theme of sexual awakening embedded within Brad and Janet’s journey. However, he emphasizes a deeper narrative thread: their car breakdown and arrival at the castle symbolize a departure from the conventional “American dream” and an entry into an uncharted future, a sentiment powerfully conveyed through the rhps songs.

The unexpected leap to the silver screen was “astonishing.” A fringe theatre production, yet to even grace London’s West End, caught the attention of the US movie industry. 20th Century Fox not only greenlit a film adaptation but also remarkably retained the original cast, with Jim Sharman directing. The studio’s sole condition was the inclusion of American actors, resulting in the casting of Barry Bostwick and Susan Sarandon as Brad and Janet. Intriguingly, their on-screen chemistry mirrored reality as they were romantically involved during filming. Despite near cancellation due to studio leadership changes, the film, propelled by its memorable rhps songs, not only survived but thrived, becoming a financial lifeline for Fox for three years and securing its legendary status in cinema.

Filming took place in the UK, at a semi-derelict Victorian gothic revival house adjacent to Hammer House of Horror studios. This location, imperfect yet atmospheric, perfectly suited the film’s aesthetic, despite the practical challenges of transporting equipment. The creation of Rocky’s birthday party scene, featuring Peter Hinwood as the bandaged creation and Transylvanian extras, stands out as a particularly enjoyable, albeit freezing, experience. The dedication of the cast is exemplified by Susan Sarandon’s performance of “Wild and Untamed Thing” while battling severe illness, a testament to the passion infused into these rhps songs.

Director Jim Sharman’s playful set, including the hidden presence of Eddie’s corpse, aimed for genuine reactions, adding an element of surprise even amidst the meticulously planned musical numbers and rhps songs. O’Brien acknowledges the film’s imperfections but embraces them as part of its kitsch charm. He points to the groundbreaking gender-bending portrayal, particularly Dr Frank N Furter’s unapologetic declaration in “Sweet Transvestite,” as empowering and Janet’s assertive sexuality in “Touch-A Touch-A Touch Me” as equally provocative for its time. These thematic elements, deeply embedded within the rhps songs, contributed significantly to the film’s cultural impact.

O’Brien personally identifies more as a lyricist, highlighting his favorite Rocky Horror line, “It’s not easy having a good time,” for its comedic pathos. He also appreciates the “quasi-gravitas” of the narrator’s verse in “Superheroes,” emphasizing the existential themes woven into the seemingly lighthearted rhps songs. Despite decades of association, his enthusiasm remains undiminished, fueled by the energy of the band, the music, and the audience’s enduring laughter and engagement with the rhps songs.

Richard Hartley, the composer, offers a concise yet insightful perspective: “Rocky Horror is just Frankenstein with a twist. Except there’s no twisting – it’s rock’n’roll.” He emphasizes the shared musical influences between him and O’Brien, drawing from artists like Chuck Berry and The Rolling Stones, evident in tracks like “Sweet Transvestite.” While acknowledging the self-indulgent nature of the rhps songs, he distinguishes them from pastiche, emphasizing their earnestness.

The initial theatrical run, despite a small venue, elicited enthusiastic audience responses. Hartley, however, maintains a more serious view, highlighting the initially serious portrayal of Dr Frank N Furter before the character’s transformative high-heeled liberation, a duality brilliantly captured by Tim Curry, who “appealed to both sexes.” For the film, makeup artist Pierre La Roche, known for his work with David Bowie, was initially brought in, but Tim Curry ultimately took charge of his iconic makeup.

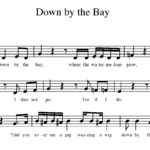

“Time Warp,” a quintessential rhps song, was a late addition during rehearsals, driven by the practical need for a dance number and to extend the show’s runtime. Hartley describes the evolution as spontaneous, with musical arrangements developing alongside rehearsals. Despite vocal challenges within the cast, the musical elements coalesced effectively.

The rhps songs‘ subversive edge, according to Hartley, stemmed from their raw, garage band-like musicality. For the film adaptation, a deliberate shift towards a more gothic sound was undertaken, incorporating musicians from Procol Harum and enriching the arrangements with strings and brass, “sweetening” it for a Hollywood audience. Despite this enhanced production, the rhps songs retained their core energy. Interestingly, all songs except “Science Fiction” were pre-recorded and mimed in the film, a decision driven by logistical rather than cost considerations.

Hartley expresses ongoing astonishment at the phenomenon Rocky Horror has become. He humorously suggests that the film’s pacing, particularly its mid-section, might have inadvertently contributed to audience participation, as viewers perhaps filled moments of perceived slowness with their own responses. Regardless of its quirks, the enduring appeal of the rhps songs and the Rocky Horror Picture Show remains undeniable, a testament to their creators’ vision and the unique cultural space they carved out.