Author J.T. Moring. Photo of J.T. Moring by Steve Covault.

What makes a song stick with us? In the vast ocean of music ever created, why do some songs resonate across generations, becoming timeless classics while countless others fade into obscurity? As a songwriter myself, I’ve always been fascinated by this question. It’s a captivating idea to delve into the anatomy of songs that have truly stood the test of time. So, let’s explore one such enduring piece: “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down.”

This song, like many gems of folk tradition, boasts origins shrouded in mystery. Its first recorded appearance was in 1925, performed by Charlie Poole and the North Carolina Ramblers. Poole’s rendition marked the beginning of the song’s journey through American music history.

Over the years, “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” has traveled under various aliases, including “The Deal” and “Deal Rag,” testament to its organic evolution within folk music circles. A diverse array of artists have embraced and reinterpreted it, from folk icons like Doc Watson and Flatt & Scruggs to the progressive sounds of the New Lost City Ramblers, David Bromberg, the Flying Burrito Brothers, and even an instrumental take by Bob Wills. The beauty of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” lies in its adaptable nature. Its themes and structure are open enough to accommodate a rich tapestry of lyrical interpretations, blending traditional verses with original lyrical additions by different performers.

Charlie Poole’s Breakthrough with “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues”

“Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues” wasn’t just a song for Charlie Poole; it was his breakthrough. It was his very first commercial recording, and remarkably, it sold over 100,000 copies—an astronomical figure for the music industry in the 1920s. Ironically, Poole’s compensation model of being paid per song recorded, rather than per unit sold, meant he didn’t fully reap the financial rewards of this hit. The verses Poole recorded paint a picture of the itinerant musician’s life, juxtaposed with the longing for a loved one left behind. The chorus introduces the intriguing “deal,” widely interpreted as a reference to gambling, likely card games. Online forums and discussions often dive into speculation about which now-obscure card game might be the origin of this “deal going down” concept.

Let’s look at the lyrics Poole sang:

Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Down to Memphis, Tennessee

Any old place I hang my hat

Looks like home to me

Now I left my little girl crying

Standing in the door

Throwed her arms around my neck

Saying ‘Honey, don’t you go’

Now I’ve been all around this whole wide world

Done most everything

I’ve played cards with the King and the Queen

Discard the ace and the ten

Chorus

Oh it’s don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Don’t let your deal go down

Before my last gold dollar is gone

Now where did you get them high top shoes?

Dress you wear so fine?

Got my shoes from a railroad man

And my dress from a driver in the mine

Who’s gonna shoe your pretty white feet?

Who’s gonna glove your hand?

Who’s gonna kiss your lily white cheeks?

Who’s gonna be your man?

Now Papa may shoe my pretty white feet

Mama can glove my hand

She can kiss my lily white cheeks

‘Til you come back again

Charlie Poole, a pioneer of early country music, whose recording of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down Blues” launched the song into popularity.

Beyond this signature song, Charlie Poole’s influence on music is profound. He’s often seen as a prototype for the “outlaw” country musician, a rebellious figure who lived as hard as he played. Based in the Piedmont region of Virginia during the interwar period, Poole was a multifaceted character: banjo virtuoso, bandleader, mill worker, baseball enthusiast, and reportedly, a moonshiner. His reputation as a hard-drinking, boisterous personality was as much a part of his persona as his music. Despite a relatively short career, cut short by his untimely death from alcoholism before age 40, Poole left behind a legacy of about 60 recorded songs. These recordings include other folk standards like “Sweet Sunny South,” “Only Old and in the Way,” “Hesitation Blues,” and “You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me.” Music lovers can discover these tracks on collections readily available online or at libraries, such as You Ain’t Talkin’ to Me: Charlie Poole and the Roots of Country Music, and Loudon Wainwright III’s Grammy-winning tribute, High Wide & Handsome: The Charlie Poole Project. Both of these collections come with insightful liner notes, adding depth to the listening experience.

The impact of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” extends beyond cover versions. It’s highly likely that the song served as a wellspring of inspiration for later compositions, most notably “Deal” by the legendary Garcia/Hunter songwriting duo of the Grateful Dead, and Bob Dylan’s poignant “When the Deal Goes Down.” These songs, while distinct, echo thematic or structural elements found in Poole’s classic, illustrating its lasting influence on songwriting.

Deconstructing the Song: Melody, Rhythm, and Harmony

To truly understand the staying power of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down,” we need to dissect its musical components: the lyrics, the melody, the rhythm, and the underlying harmony or chord progression.

One interesting aspect is the presence of what are known as “floating lyrics.” These are verses that migrate across various folk songs, appearing in different contexts and narratives. The last three verses of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” are prime examples. Variations of these verses can be found in numerous other folk songs, including “He’s Gone Away,” “The Storms Are on the Ocean,” Woody Guthrie’s “Who’s Going to Shoe Your Pretty Little Feet,” “Hop High My Lula Gal,” and even the deeply rooted spiritual, “John Henry.” This sharing of lyrical phrases underscores the communal and evolving nature of folk music.

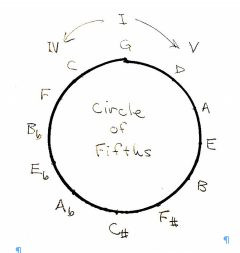

Circle of Fifths chart, illustrating the relationships between musical keys and chords, crucial to understanding the progression in “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down”.

Charlie Poole’s rendition of “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” is characterized by an upbeat tempo and a lively, syncopated rhythm. However, the song’s inherent structure proves remarkably adaptable. Musicians have molded it to fit diverse styles and tempos, showcasing its versatility.

Structurally, the song follows a common verse-chorus form, often described as A-B repetition, or sometimes more extended patterns like A-A-B or A-A-A-B. Within the verses, the two couplets generally share the same melodic phrasing, creating a sense of familiarity and ease. Interestingly, the chorus melody and chord structure closely mirror those of the verse, contributing to the song’s cohesive feel.

Poole’s melody itself is distinctive, featuring a striking upward leap of a full octave almost immediately, for example, on the word “around” in the opening line, and again on the first and third iterations of “deal” in the chorus. This melodic jump adds a dramatic flair and is reminiscent of similar intervals found in other folk tunes like “Little Maggie.” While Poole’s melody is impactful, other artists have successfully adapted less vocally demanding melodies while retaining the underlying chord structure that defines the song.

Given the fluidity of the verses, the somewhat ambiguous chorus, and a rhythm that isn’t overtly unique, what truly anchors “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” as such a resonant and enduring song? I propose that the key lies in its exceptionally compelling chord progression.

The Power of Chord Changes: A Circle of Fifths Journey

“Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down” is built upon a four-chord progression that repeats twice within each verse and twice in each chorus. Expressed in Roman numeral notation, this progression is: VI—II—V—I.

In the key of G, which Poole frequently used (a favored key for the five-string banjo), these chords translate to E-A-D-G. If transposed to the key of C, the progression becomes A-D-G-C.

For those with some musical background, this sequence might sound familiar. It’s a variation of the circle of fifths (or circle of fourths) progression. Let’s briefly explore this concept. While the circle of fifths can become a complex topic with specialized terminology, the basic idea is quite accessible. In music theory, “I” (the “one” chord) signifies the tonic, or the key center of the song—in our example, G. Moving to the fifth note of the G major scale and constructing a chord on that note yields the “V” chord, which is D. Following this pattern, the V chord of D is A, and the V chord of A is E. Continuing this process eventually leads back to G, completing a cycle through all twelve musical tones—hence, the circle of fifths.

Conversely, because D is the V chord of G, G is the IV chord of D. Therefore, tracing the same sequence in the opposite direction traverses the circle of fourths. In the circle of fifths diagram, moving clockwise from a chord lands on its V chord; moving counter-clockwise lands on its IV chord.

The chords most intimately related to the tonic are the IV and V chords, positioned adjacently on the circle of fifths. These three chords—I, IV, and V—form the backbone of countless songs, encompassing all the notes of the major scale. Many folk songs, and indeed, much popular music, are built using just these fundamental chords—hence the common reference to “one-four-five” songs.

Acoustically and psychologically, the V chord generates a sense of musical tension. This tension naturally seeks resolution, which is powerfully achieved when followed by the I (tonic) chord. The V-I cadence is a cornerstone of Western harmony, providing a satisfying sense of closure. Countless songs conclude with a V-I progression precisely for this reason—it simply feels resolved.

Now, let’s revisit the chord progression in “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down”: E-A-D-G. Notice that each transition within this sequence functions as a V-I resolution in a related key. E-A is a V-I in A, A-D is a V-I in D, and D-G is a V-I in G. Instead of a single resolution at the end of the phrase, we experience three! This cascade of resolutions, I believe, is a significant contributor to the song’s subconscious appeal. Furthermore, the initial transition from G to E (I-VI) at the start of the sequence introduces a dramatic and less common harmonic movement in folk music, adding another layer of intrigue.

From “Deal” to “Alice’s Restaurant”

Intriguingly, this chord progression is also embedded within the more complex sequence found in Arlo Guthrie’s epic “Alice’s Restaurant,” among other songs. Perhaps the exploration of chord progressions in long-form storytelling songs is a topic for a future discussion.

In the meantime, for those interested in hearing this progression in action and learning to play “Don’t Let Your Deal Go Down,” I’ve created a short video demonstrating a guitar arrangement in the key of E. Feel free to sing along and explore this enduring song further: https://youtu.be/pd13-5in7jc