Many years ago, tuning into the radio, I stumbled upon a piece of music that was unlike anything I had heard before. It was a repetitive violin sequence, hypnotic in its persistent rhythm and subtly evolving variations. Initially, I questioned if it was a record stuck in a loop, but the gradual shifts in the melody revealed a deliberate composition at play. This twenty-minute piece completely captivated me; it was Philip Glass’s “Einstein On The Beach,” a truly remarkable and unique auditory journey. What struck me most was the sheer dedication and intense focus required from the musicians to execute such lengthy compositions with minimal overt changes. Glass has since risen to prominence, becoming arguably the most recognized living classical composer, perhaps alongside Michael Nyman, largely due to their contributions to film scores.

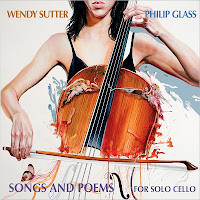

Now, turning our attention to “Songs And Poems,” an album crafted for solo cello, it’s an offering that demands attention. In contrast to some of Glass’s more famously repetitive works, this collection exhibits a different approach. While repetition is present, it’s utilized more in a Bach-like manner, as thematic patterns to be explored and developed. As one might anticipate from pieces written for the cello, a sense of melancholy pervades, with darker undertones emerging in the central and later sections. However, the overarching character remains classical, marked by its rigorous structural integrity, delicate nuances, and refined execution. Wendy Sutter, a cellist also associated with “Bang On A Can,” delivers an exceptional performance on this album. Her playing is precise, emotionally resonant, and imbued with a keen sense of pacing. Sutter performs on her “ex vatican stradivarius” from 1620, an instrument of singular pedigree, renowned for its profound and richly warm timbre.

Philip Glass, renowned composer, whose album 'Songs and Poems' offers a unique listening experience reminiscent of the diverse music of 2008.

Philip Glass, renowned composer, whose album 'Songs and Poems' offers a unique listening experience reminiscent of the diverse music of 2008.

Up to this point, the album is seamless, but then comes an abrupt shift. The final four tracks deviate from the solo cello format, presenting pieces from “Naqoyqatsi” that were ultimately not included in the film. On these tracks, Sutter is joined by David Cossin on percussion and Glass himself on piano. These pieces create a jarring stylistic contrast with the rest of the album. They adopt a distinctly different musical language, leaning towards a more romantic and less austere sensibility, diminishing the dramatic intensity established in the solo cello works.

It’s frankly baffling that record labels sometimes exhibit such a lack of consideration, not only for the artists but especially for the listening audience, by disrupting the cohesiveness of an otherwise outstanding album. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with the concluding four tracks in isolation, their inclusion in this context feels completely misplaced. It’s akin to appending unused Beatles tracks from 1962 onto “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” simply because there was remaining space on the record. Does it matter if an album is only thirty minutes long? Quality should always take precedence over quantity. The addition of these tracks was, to put it mildly, frustrating. And if truth be told, the album cover’s overtly kitschy artwork is equally discordant, clashing sharply with the sophistication of the music within. However, these missteps should not dissuade you from experiencing this album. Take my advice: re-record it, omitting the final four tracks. By doing so, you’ll uncover a genuine musical treasure.

Explore and download the initial 7 tracks from iTunes.