“Just because a man lacks the use of his eyes doesn’t mean he lacks vision,” Stevie Wonder wisely stated, a clear message to anyone who underestimated his boundless imagination. In the early 1970s, Wonder embarked on an uncharted musical journey, distancing himself from the manufactured pop of his “Little Stevie, the Boy Genius” Motown beginnings. This bold path culminated in 1976 with the release of Songs in the Key of Life, a sprawling double album with a bonus EP, totaling 21 songs, a monumental achievement for the then 26-year-old artist. This collection is a testament to a young, creatively liberated artist fully realizing his potential, embracing his ambition, and wielding his musical prowess.

Considered the pinnacle of Wonder’s remarkable “classic period” – an era of unparalleled creativity that also gave us Music of My Mind (1972), Talking Book (1972), Innervisions (1973), and Fulfillingness’ First Finale (1974) – Songs in the Key of Life was the ambitious culmination of everything he had achieved musically up to that point. Motown founder Berry Gordy aptly summarized in a 1997 documentary, “He took his life experience and put them all into Songs in the Key of Life. And it worked.”

Having been signed to Gordy’s Motown label at the tender age of 11, Stevie Wonder had grown into a confident adult, boasting a decade-long string of hits. However, a “quarter-life crisis” began to creep in. The celebrated musician started openly contemplating leaving the music industry altogether, considering a move to Ghana, a place he believed held the roots of his ancestry. His vision was to dedicate his considerable energy to humanitarian work, particularly assisting children with disabilities. This internal shift was mirrored externally as he traded his signature mod suits for vibrant dashiki tunics, a visual representation of his evolving mindset.

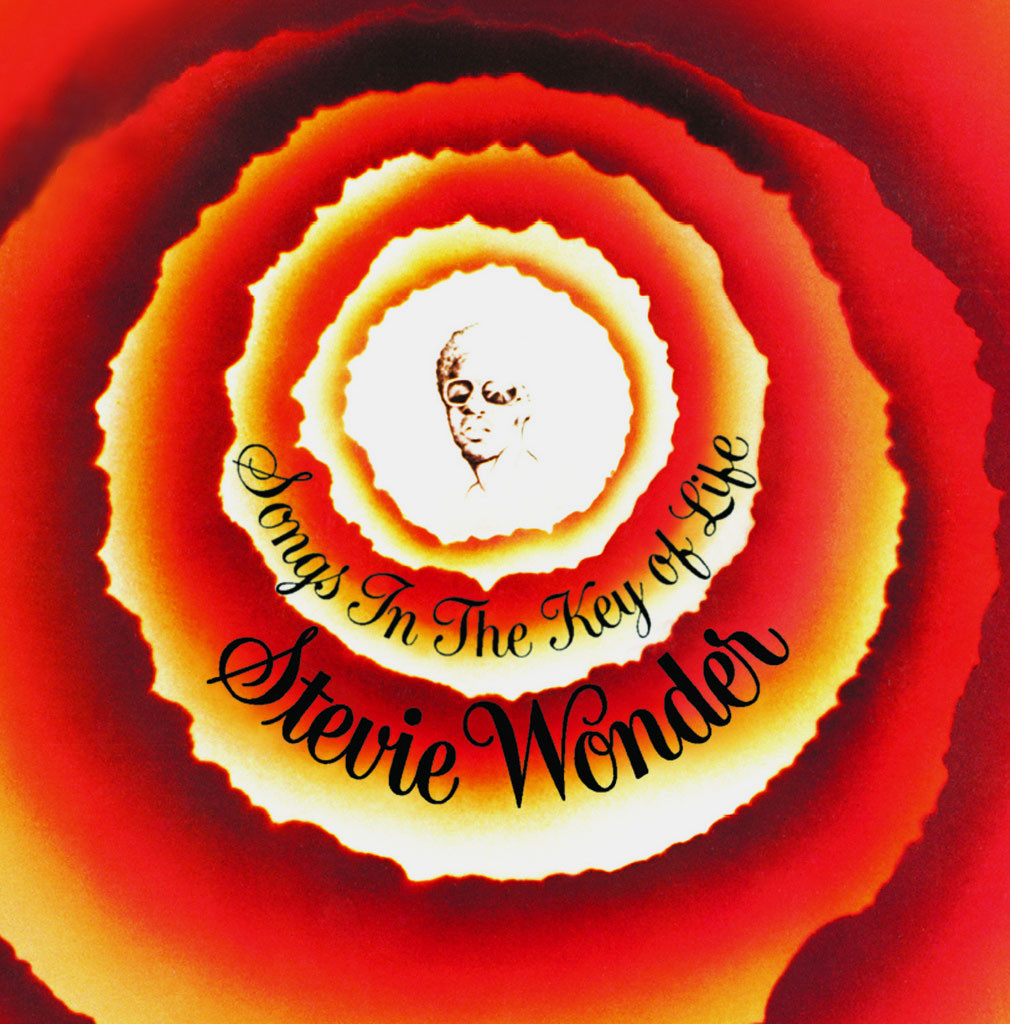

Stevie Wonder's visionary album Songs in the Key of Life, a crowning achievement of his career, showcasing his creative emancipation and musical genius.

Stevie Wonder's visionary album Songs in the Key of Life, a crowning achievement of his career, showcasing his creative emancipation and musical genius.

Wonder had briefly mentioned his fascination with Ghana in a 1973 Rolling Stone interview, and these abstract notions soon began to solidify. In a Los Angeles press conference the following March, he tentatively announced a farewell concert tour scheduled for the end of 1975 – coinciding with the expiration of his Motown contract – with all proceeds aimed at supporting Ghanaian charities.

“I’ve heard of great needs in that part of the world, the African countries,” he shared with the Associated Press. “I believe that you have to give unselfishly… You can sing about things and talk about things, but if your actions don’t speak louder than your words, you’re nothing.” While these were noble sentiments, some observers cynically interpreted this dramatic farewell tour as a strategic maneuver to gain leverage with Motown during contract renegotiations.

However, Wonder arguably didn’t need leverage. Motown’s dominance had been challenged in the early seventies due to shifting music trends and economic downturn. Knowing they risked losing their most consistent hitmaker to philanthropy – or to enticing offers from rival labels like Epic and Arista Records – Berry Gordy and Motown were prepared to make an unprecedented offer.

Wonder enlisted high-powered lawyer Johanan Vigoda to negotiate his extensive list of demands with new Motown president Ewart Abner and chairman Gordy. Gordy described these negotiations in his memoirs as “the most grueling and nerve-racking we ever had.” When the agreement was finalized, Wonder secured a groundbreaking seven-year contract that included a $13 million advance (potentially reaching $37 million if he exceeded his minimum album output), a generous 20 percent royalty rate, and control over his publishing rights. At the time, it was the most lucrative deal ever made in the music industry. Time magazine even highlighted that it surpassed the combined contracts of Elton John and Neil Diamond.

“In those days $13 million was a lot of money,” Gordy exclaimed in the 1997 Classic Albums: Songs in the Key of Life documentary. “I’d heard that was an unprecedented deal, the most that had ever been paid. But I had to do it, because there was no way I was going to lose Stevie… I was shaking in my boots!”

Beyond the financial windfall, the contract granted Wonder complete creative autonomy. He could record anywhere, collaborate with any artist, and even had veto power over potential singles. A planned triple-disc greatest hits collection was promptly canceled at Wonder’s request, with all 200,000 copies reportedly destroyed. Remarkably, Motown would require Wonder’s explicit permission should the label ever be considered for sale in the future. The Beatles, Elvis Presley, Frank Sinatra – none wielded such power over their labels. This deal unequivocally solidified Wonder’s position as Motown’s preeminent artist.

“He broke tradition with the deal – legally, professionally – in terms of how he could cut his records and where he could cut,” Vigoda explained to Rolling Stone‘s Ben Fong-Torres. “And in breaking tradition he opened up a future for Motown. They never had an artist in 13 years. They had single records, they managed to create a name in certain areas, but they never came through with a major, major artist.”

While the contract significantly benefited Wonder, he recognized Motown’s crucial role in his journey. The label was a beacon of African-American success.

“I’m staying at Motown, because it is the only viable surviving black-owned company in the record industry,” Wonder declared in a statement announcing the deal. “Motown represents hopes and opportunity for new as well as established black performers and producers. If it were not for Motown, any of us just wouldn’t have had the shot we’ve had at success and fulfillment. It is vital that people in our business – particularly the black creative community, including artists, writers and producers – make sure that Motown stays emotionally stable, spiritually strong and economically healthy.”

Three decades later, in the Classic Albums documentary, Wonder continued to express his gratitude for Gordy’s faith. “He was brave enough to take the chance – to take that challenge to say, ‘You know what? I believe in him enough to do this. I believe in the gamble.’ And he was a smart man.”

With the contractual matters settled, Wonder immersed himself in his next musical endeavor – his 18th album since 1962.

He carried momentum from his previous release, 1974’s Fulfillingness’ First Finale. That album was a relatively introspective and somber collection, marked by self-reflection and even hints of anger, exemplified by the Nixon-criticizing track “You Haven’t Done Nothin’”. Initially intended as a double album, when those plans were shelved, Wonder announced that the surplus tracks would form a sequel, Fulfillingness’ First Finale Part II (or, playfully, Fulfillingness’ Second Finale).

In late 1974, Wonder previewed the work-in-progress to journalists from Crawdaddy and Melody Maker, playing a song called “The Future,” featuring the cautionary line: “Don’t look at the world like a stranger, cause you know we are living in danger.” This melancholic song was “fantastically influenced” by the televised police ambush of the Symbionese Liberation Army, a radical left-wing group on the run with kidnapped heiress Patricia Hearst, an event that resulted in multiple fatalities. “Livin’ Off the Love of the Land” was similarly bleak, with lyrics like “Seems the wisdom of man hasn’t got much wiser,” and “Seems to me that fools are even more foolish.”

Perhaps recognizing that such overtly pessimistic songs might alienate his audience and negatively impact commercial success, these tracks were shelved, and Fulfillingness’ Second Finale was abandoned. Wonder decided to start anew with his next project, tentatively titled Let’s See Life the Way It Is. The definitive title came to him in a dream: Songs in the Key of Life.

For Stevie Wonder, the title Songs in the Key of Life served as a personal challenge to broaden his songwriting scope. “I challenged myself [to write] as many different things as I could, to cover as many topics as I could, in dealing with the title and representing what it was about,” he explained in Classic Albums. “The title would give me a challenge, but equally as important as a challenge it would give me an opportunity to express my feelings as a songwriter and as an artist.”

He embraced this challenge wholeheartedly, working with unwavering dedication. Non-stop recording sessions spanned two and a half years, across both coasts, and in four studios: Crystal Sound in Hollywood, New York City’s Hit Factory, and the Record Plant studios in Los Angeles and Sausalito. He was a constant presence in these studios, sometimes for 48-hour stretches, pursuing his creative muse with a rotating team of engineers and supporting musicians. Over 130 individuals contributed to the recording process, including luminaries like Herbie Hancock, George Benson, “Sneaky Pete” Kleinow, and Minnie Riperton. “If my flow is goin’, I keep on until I peak” became Wonder’s guiding principle.

“It went on for two years almost every day, many hours and huge amounts of material,” recalled John Fischbach, who co-engineered the majority of the sessions with Gary Olazabal. “I guess it was really his most prolific time. He did more songs in those two years I think than he had done before.”

While the exact number remains unconfirmed, Wonder claimed to have recorded hundreds of tracks during the Songs in the Key of Life sessions – the vast majority of which remain unreleased. This prolific output is corroborated by Fischbach, who estimated “something like 200 songs” in various stages of completion. “Some would be sketched out, some were more finished than others and we just kept working until he had what he wanted,” he stated.

Olazabal described Wonder’s creative process as “frighteningly spontaneous,” often resulting in late-night or early-morning calls to collaborators. Gary Byrd recounted a particularly demanding experience while co-writing lyrics for “Village Ghetto Land.” He had spent three months meticulously crafting the lyrics to what he believed was the complete song. Then, Wonder called from the studio, casually mentioning he had added another verse and asking if Byrd could write new lyrics in the next ten minutes, as the band was waiting.

“There are ‘sessions’ and then there’s Stevie Time,” keyboardist Greg Phillinganes humorously noted on WBEZ’s Sound Opinions podcast in 2006. “We didn’t have formal sessions. We went to the studio and that was where you were.”

In addition to his dedicated team, Wonder possessed a secret weapon: a cutting-edge analog synthesizer called the Yamaha GX-1. This colossal instrument featured three keyboards, multi-octave foot pedals, a ribbon controller, a vast array of buttons for sound recall and pitch modulation, and even an integrated bench. “It could house a family of eight,” Phillinganes exaggerated playfully. “It was huge.”

The GX-1’s immense size was matched by its exorbitant price. Retailing for a staggering $60,000 (equivalent to around $320,000 today), it was intended as a prototype for future consumer synthesizers, and consequently, only a handful were ever produced and sold. Most ended up in the hands of music industry giants like Keith Emerson of Emerson, Lake and Palmer, John Paul Jones of Led Zeppelin, and Benny Andersson of ABBA. Wonder acquired two.

The GX-1 was ideally suited to Wonder’s multi-instrumental talents. Its realistic (for the time) instrument samples allowed him to create complex orchestral arrangements single-handedly. Unlike other synthesizers of that era, it was polyphonic, enabling him to play multiple notes simultaneously and construct rich backing tracks much more efficiently.

Wonder nicknamed the metallic behemoth “The Dream Machine” and immediately utilized it extensively on Songs in the Key of Life, most notably on “Village Ghetto Land” and “Pastime Paradise.”

“Pastime Paradise” begins with a captivating, spiraling fugue, borrowing its first eight notes from Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Prelude No. 2 in C Minor.” Intended to evoke the feel of the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby,” the unsettling instrumental phrase is further enhanced by the sound of a reversed gong, foreshadowing the Hare Krishna chanting heard during the song’s fade-out. The inclusion of Hare Krishna devotees was a spontaneous creative decision.

“Gary [Olazabal] rounded them up on Hollywood Boulevard,” Fischbach recalled to Sound on Sound. “We had decided it would be great to have them on the song, so he went and talked to a bunch of those people and made arrangements for them to come to the studio.”

Crystal Studios was located on the east side of Hollywood, not far from the Self-Realization Fellowship headquarters. “They walked in line all the way from the Self-Realization Fellowship,” Olazabal added. “There must have been about a hundred of them, chanting and praying as they showed up to perform on the song, but Stevie never showed up. We didn’t know what to do, and so we just let them go into the studio. The main room was not very live-sounding, but it was very big. Well, they were in there for hours, chanting – they didn’t really interact much in any other way – and when Stevie didn’t appear we knew they’d have to walk all the way back and return another day.” Despite Wonder’s absence, the Hare Krishnas remained positive. “There was not a lot of hostility,” Olazabal noted. “Except from us. It wasn’t easy to listen to that chanting for hours on end.”

The West Angeles Church of God Choir was also incorporated into the outro, performing a rendition of the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome,” interwoven with the Hare Krishna chants. This fusion of spiritual and social consciousness, the eternal and the urgent, gave voice to the profound dreams residing within the young maestro.

However, it was another vocal contribution that resonated most deeply on a personal level. Wonder became a father on February 5th, 1975, when his partner Yolanda Simmons gave birth to Aisha Morris. “She was the one thing that I needed in my life and in my music for a long time,” he confided to Women’s Own magazine shortly after. “Isn’t She Lovely,” a joyous ode to parenthood, is perhaps the most direct musical expression of Wonder’s newfound inspiration. While the actual birthing sounds at the song’s beginning are from another infant, Aisha’s laughter and splashing in the bathtub with her father can be heard during the extended fade-out.

Wonder’s sister, Renee Hardaway, also contributed vocals to Songs in the Key of Life, delivering the playfully scolding “You nasty boy!” that punctuates the album’s lead single, “I Wish.” The last song completed for the project, its initial lyrics explored themes of war and “cosmic spiritual stuff” until Wonder attended a Motown company picnic. The label had served as a formative environment for the former child star, and the enjoyable afternoon sparked a wave of nostalgia. He quickly wrote new lyrics reflecting on those early days and, at 3 a.m., called bassist Nathan Watts – who had just returned home from a long recording day. “Stevie called and said, ‘I need you to come back,” Watts recounted to Bassplayer. “I’ve got this bad song!”

“Saturn,” a track featured on the album’s bonus EP, A Something’s Extra, also originated from a nostalgic reflection. The lyrical setting was initially “Saginaw,” Wonder’s Michigan hometown, intended as a tribute to his roots in the vein of the Jackson 5’s “Goin’ Back to Indiana.” However, the song’s direction shifted to outer space when guitarist Mike Sambello (later known for the Flashdance hit “Maniac”) misheard the title as the ringed planet. Much like the past, Saturn is portrayed as an idealized utopia, just beyond reach.

Traces of Wonder’s family and personal history are woven throughout the album. His brother Calvin Hardaway co-wrote “Have a Talk With God,” and his former wife, Syreeta Wright, contributed backing vocals to “Ordinary Pain.” Some even speculate that “Ebony Eyes” – with its reference to a “Miss Beautiful Supreme” – is a tribute to Wonder’s childhood admiration for fellow Motown artist Diana Ross. “I had a crush on her,” he admitted to Vanity Fair in 2008. “When I came to Motown, she walked me around the building and showed me different things – she was wonderful.”

A compelling alternate theory suggests the song is actually an homage to another Supreme, Florence Ballard, who tragically passed away in February 1976 from cardiac arrest at the age of 32. She had been dismissed from the Supremes nine years prior due to erratic behavior linked to substance abuse and resentment at being overshadowed by Diana Ross. Her career subsequently declined, plagued by lawsuits, domestic incidents, poverty, and alcoholism.

Wonder would have been familiar with Ballard. A subtle acknowledgement of her untimely death would align with his ambition to explore all facets of life – even mortality – within Songs in the Key of Life.

Mortality, and musical immortality, are central to a far more explicit tribute, the exuberant “Sir Duke.” This song honors jazz legend Duke Ellington, a significant influence on a young Stevie Wonder, who had passed away in 1974 before they could collaborate. “I knew the title from the beginning but [I] wanted it to be about the musicians who did something for us. So soon they are forgotten. I wanted to show my appreciation.” He namechecks Count Basie, Glenn Miller, Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong, and Ella Fitzgerald among the pantheon of greats, perhaps with a premonition that his own name would one day join them.

And indeed, it has. The Songs in the Key of Life sessions produced some of the most exceptional songs in his entire catalog, including the celestial “Knocks Me off My Feet,” the intricate harmonies of “Love’s in Need of Love Today,” and the Herbie Hancock-assisted “As.”

After the foundational recordings were completed, Wonder insisted on endlessly remixing the tracks, exploring countless sonic possibilities. “It was a marathon, and at times we wondered if it would ever finish,” Olazabal recalled. “We had T-shirts with ‘Are We Finished Yet?’ printed on them, as well as others with ‘Let’s Mix ‘Contusion’ Again.’ Without exaggeration, we must have mixed that track at least 30 times. It became part of the joke of our lives.”

Wonder would playfully wear these T-shirts around Motown headquarters, teasing the increasingly anxious executives who had never waited so long for an album. “Nobody thought this project would go on as long as it did,” Fischbach confirmed. Deadlines came and went, largely disregarded by the artist, while the label coped with over a million advance orders for an album that was, technically, still unfinished.

By the fall of 1976, Stevie Wonder declared himself ready. He had created a double LP and bonus EP overflowing with musical innovation. Songs in the Key of Life was a groundbreaking fusion of funk, soul, pop, and jazz, enhanced by cutting-edge technology. Remarkably, this collection of forward-thinking musical brilliance was unveiled to the world at the idyllic Long View Farm in rural North Brookfield, Massachusetts.

However, the Long View Farm event was the final flourish in a long and elaborate rollout. On September 7th, 1976, at 7:30 a.m., international press gathered in the lobby of Manhattan’s elegant Essex House. They enjoyed a complimentary breakfast before being escorted onto three buses, which drove them to Kennedy International Airport – but not before passing through Times Square for a glimpse of the massive $75,000, 60-by-400-foot billboard that had been promoting the album for four months. Soon, they were airborne in a chartered DC-9, well-stocked with champagne and appetizers. Upon landing at a small airport in Worcester, Massachusetts, the journalists were transferred to a fleet of school buses for a short ride to the listening party.

Long View Farm was a sprawling 143-acre equestrian estate that had recently been converted to include a state-of-the-art recording studio (used by renowned artists such as the Rolling Stones, Cat Stevens, Aerosmith, and the J. Geils Band). Guests were treated to lavish meals of roast beef, pie, and more champagne while awaiting Wonder’s arrival. He made a grand entrance, dressed in a flamboyant cowboy outfit, complete with a ten-gallon hat, leather fringe, and a gun holster emblazoned with the words “Number One With A Bullet.” The entire event cost Motown upwards of $30,000.

“Let’s pop what’s poppin’,” he announced as he pressed play on the reel-to-reel tape machine, finally releasing the music that had been developing in the studio – and in his soul – for so long.

Songs in the Key of Life immediately soared to the top of the charts. It became only the third album in history to debut at Number One, holding that position for an impressive 14 weeks. It also garnered Wonder four Grammy Awards, which he accepted via satellite from Nigeria, where he was exploring his musical heritage. The experience was slightly marred by a poor connection, leading presenter Andy Williams to awkwardly ask, “Stevie, can you see us?”

Four decades have not diminished the album’s power and breathtaking scope. It has been cited as a favorite by musical icons like Prince, Whitney Houston, Michael Jackson, Mariah Carey – and Stevie Wonder himself. “Of all the albums, Songs in the Key of Life I’m most happy about,” he told Q magazine in 1995. “Just the time, being alive then. To be a father and then letting go and letting God give me the energy and strength I needed.”