In the annals of music history, few record labels have left as indelible a mark as Motown Records. Founded in Detroit in 1959 by the visionary Berry Gordy Jr., with a borrowed sum of just $800, Motown rapidly evolved from a fledgling enterprise into a cultural phenomenon. Within a year of its inception, Motown celebrated its first million-selling record with The Miracles’ “Shop Around.” By 1969, the label had become a dominant force in pop music, placing numerous records in the Billboard Top 10 and profoundly shaping the sound of a generation. Motown’s success was rooted in its unique, and at times paradoxical, blend of assembly-line efficiency and individual artistic brilliance, integrationist ideals and black empowerment, and fierce competition intertwined with a strong sense of community. Smokey Robinson, the label’s prolific songwriter and artist, aptly described this familial atmosphere, stating, “I was so happy whenever I got a hit record on one of the artists because they were my brothers and sisters.”

Motown’s initial sonic identity, defining “the sound of young America” in the mid-1960s, was characterized by the sophisticated pop elegance of artists like Mary Wells, The Miracles, Marvin Gaye, and The Temptations, alongside the exuberant girl-group sounds of The Supremes, The Marvelettes, and Martha and the Vandellas. Later, pioneering artists Marvin Gaye and Stevie Wonder challenged Berry Gordy’s artistic control, leading to the creation of groundbreaking, socially conscious albums in the 1970s such as What’s Going On and Innervisions. These albums broadened Motown’s artistic scope while staying true to the label’s hit-making essence. Throughout the funk, disco, and easy-listening eras, Motown continued to produce stellar music through stars like Smokey Robinson, The Commodores, Diana Ross, and Michael Jackson. In the 1980s and 1990s, hitmakers such as Rick James, Lionel Richie, DeBarge, and Boyz II Men ensured Motown’s continued presence on the airwaves.

Selecting just 100 of the Best Motown Songs is a formidable task. Marking the 60th anniversary of The Marvelettes’ groundbreaking Number One hit, “Please Mr. Postman,” it’s evident that the joy and power of Motown’s music remain undiminished. Whether you’ve heard timeless classics like “My Girl,” “Come See About Me,” or “The Tracks of My Tears” countless times, or encountered them in movie soundtracks, their freshness is undeniable. Similarly, the radical spirit of tracks like “What’s Going On” and “Living for the City” continues to resonate profoundly in today’s world. Beyond the famous hits, there’s a wealth of lesser-known gems waiting to be discovered within the vast Motown catalog.

-

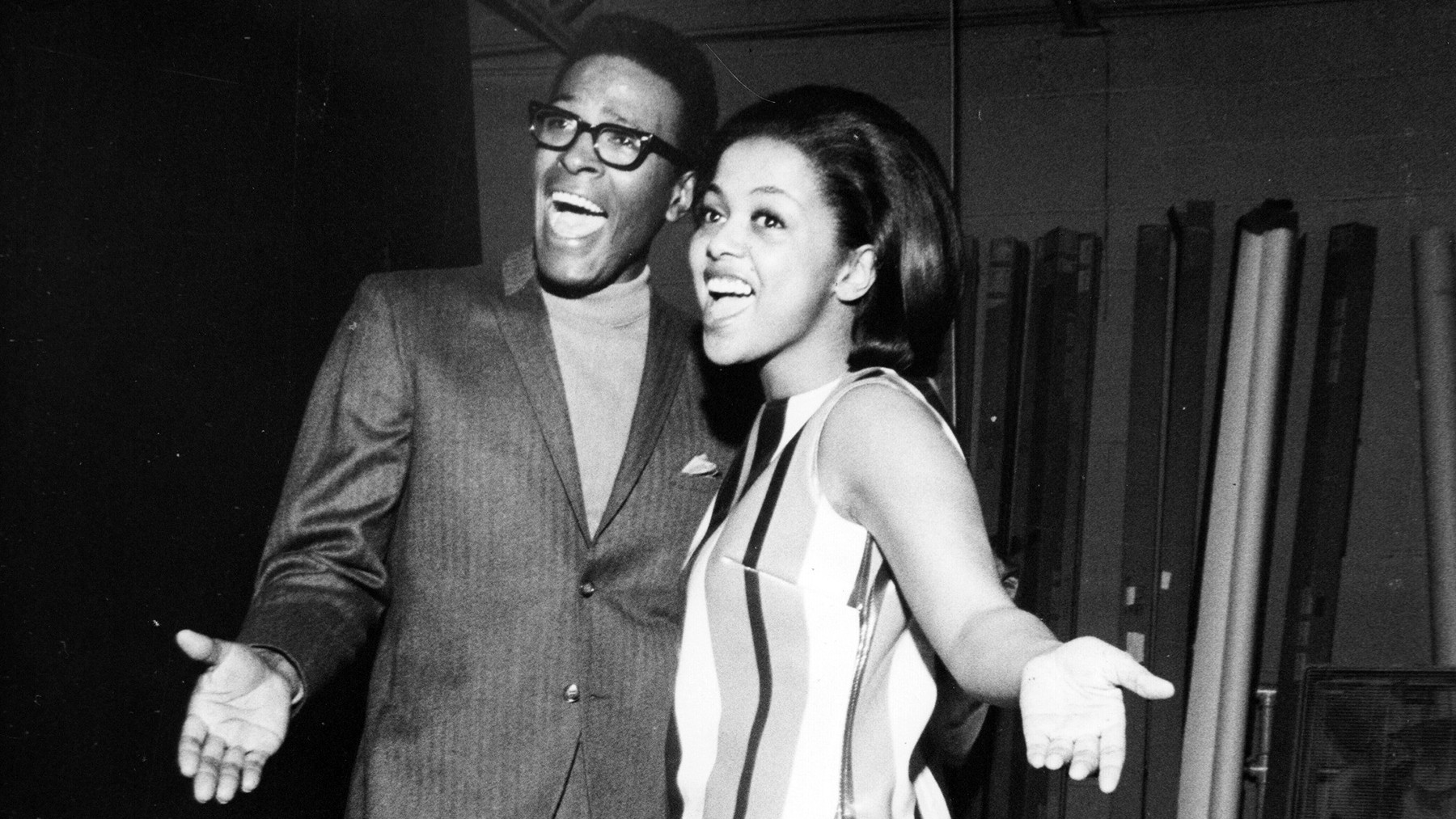

Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, “Shop Around” (1960)

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

To truly appreciate Berry Gordy’s genius in refining Detroit R&B for a broader pop audience without diluting its essence, one must compare the two versions of Smokey Robinson’s 1960 classic, “Shop Around,” recorded by The Miracles. Initially released locally, Gordy had second thoughts, deeming the first version “too slow, not enough life.” He promptly brought the group back to the studio to record a more upbeat rendition. This second version became Motown’s first million-selling record and a Number One R&B hit. On the pop charts, “Shop Around” was narrowly kept from the top spot only by Lawrence Welk, highlighting its broad appeal and impact. —K.H.

Martha and the Vandellas, “Jimmy Mack” (1966)

Martha Reeves of Martha and the Vandellas, 1965, in a studio portrait with band members, highlighting their hit "Jimmy Mack".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Martha Reeves of Martha and the Vandellas, 1965, in a studio portrait with band members, highlighting their hit "Jimmy Mack".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

“Jimmy Mack” stands out in the Motown catalog for its intricate backstory and multiple layers of meaning. This song of yearning for a lost lover transcends mere melancholy thanks to the dynamic songwriting of Holland-Dozier-Holland and the energetic rhythms provided by the Funk Brothers. The title itself was inspired by a BMI awards ceremony where songwriter Ronnie Mack of “He’s So Fine” was posthumously honored. Lamont Dozier recounted, “I was so taken with the mother and her little speech — that stayed with me, so I came up with the song.” Although initially recorded in 1964, “Jimmy Mack” was shelved until 1967. Its release coincided with the height of the Vietnam War, adding another layer of interpretation as the longing for a returning loved one resonated deeply with the times, making it a poignant and timely hit. —D.B.

Dennis Edwards feat. Siedah Garrett, “Don’t Look Any Further” (1984)

Dennis Edwards, former lead singer of The Temptations, performing in 1983, known for "Don't Look Any Further".Image Credit: Ebet Roberts/Redferns/Getty Images

Dennis Edwards, former lead singer of The Temptations, performing in 1983, known for "Don't Look Any Further".Image Credit: Ebet Roberts/Redferns/Getty Images

“Don’t Look Any Further” features another groundbreaking rhythm section within Motown’s extensive discography. The track is driven by a relentless snare drum and a distinctive four-part bass riff. This hit was Dennis Edwards’ only major success outside of The Temptations, significantly enhanced by Siedah Garrett, who later co-authored Michael Jackson’s “Man in the Mirror.” Edwards, even without his Temptations colleagues, delivers vocals with a raw, powerful force reminiscent of Teddy Pendergrass. “Don’t Look Any Further,” akin to the Mary Jane Girls’ “All Night Long,” bridges early funk with the burgeoning sound of hip-hop. Older audiences might recognize its roots in “Abraxame” by Barrabas, a track popular in early Seventies New York clubs. Hip-hop fans will note the iconic bass line, famously sampled by Eric B. and Rakim for their masterpiece “Paid in Full,” cementing its legacy and influence. —E.L.

The Velvelettes, “He Was Really Sayin’ Somethin’” (1964)

The Velvelettes, 1965, in a studio portrait, known for their hit "He Was Really Saying Something".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

The Velvelettes, 1965, in a studio portrait, known for their hit "He Was Really Saying Something".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Formed at Western Michigan University, The Velvelettes, while not reaching the heights of The Marvelettes, Vandellas, or Supremes, produced two exceptional singles in 1964: “Needle in a Haystack” and the lyrically astute and musically sophisticated “He Was Really Saying Something.” This song became a modest hit for the group and later gained broader recognition in the 1980s when New Wave group Bananarama released a faithful and popular cover version in 1983, introducing it to a new generation of music fans. —J.D.

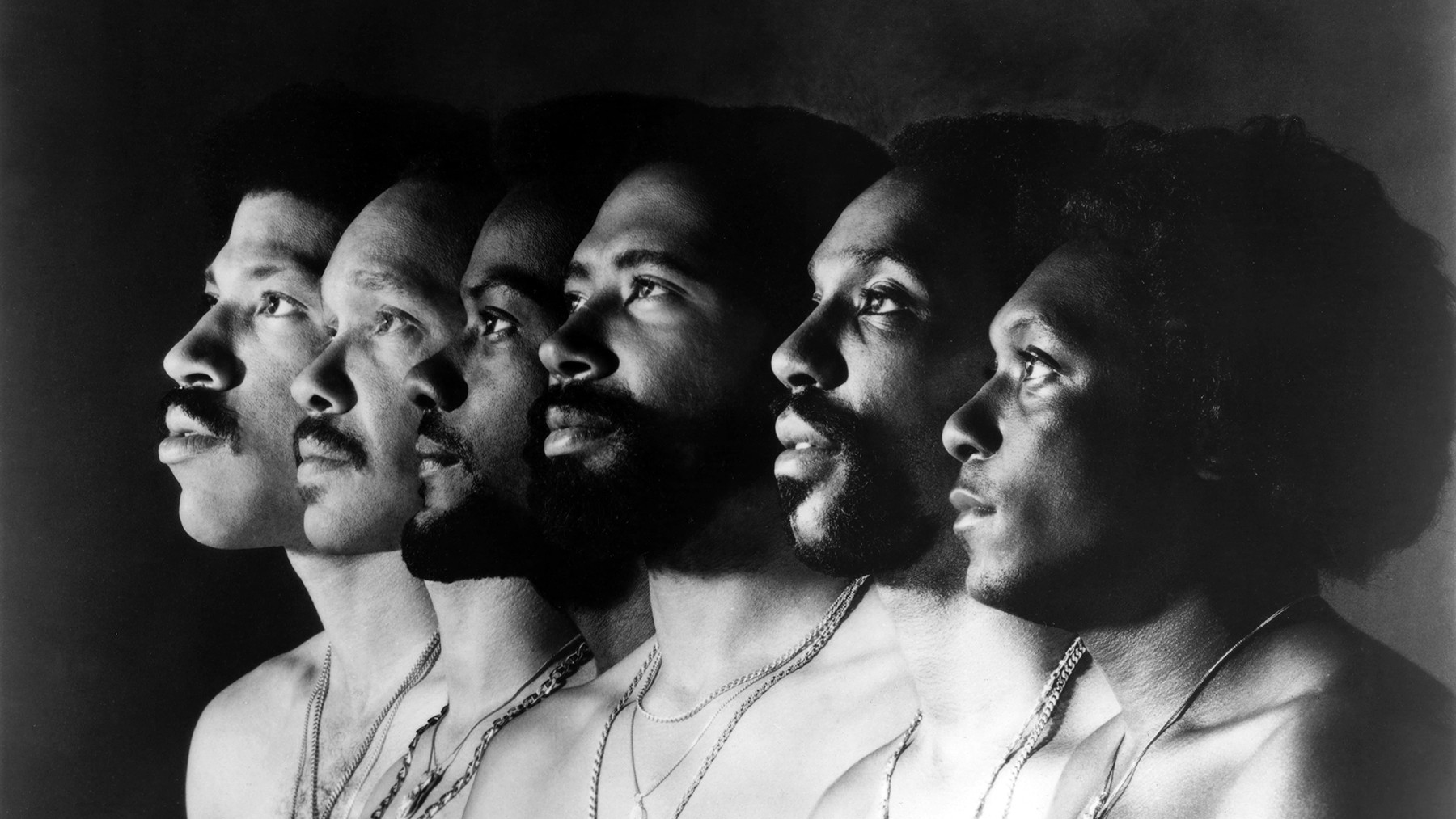

The Originals, “Baby, I’m for Real” (1969)

The Originals, a vocal group known for "Baby, I'm for Real", in a promotional portrait from the 1960s.Image Credit: James Kriegsmann/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Originals, a vocal group known for "Baby, I'm for Real", in a promotional portrait from the 1960s.Image Credit: James Kriegsmann/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

For much of the 1960s, The Originals were primarily known as backup singers. Their breakthrough came with “Baby, I’m for Real,” produced by Marvin Gaye and co-written with his then-wife, Anna Gordy Gaye. This track, both sparse and tender, evoked the doo-wop era at a time when soul music was embracing more psychedelic and elaborate arrangements. “Baby, I’m for Real” is a straightforward declaration of love and commitment, launching The Originals into the spotlight after years behind the scenes. They followed up the next year with “The Bells,” another hit co-written and produced by Gaye, solidifying their place in Motown history. —J.D.

Rare Earth, “I Just Want to Celebrate” (1971)

Rare Earth, an all-white rock band signed to Motown, in a 1971 band portrait, famous for "I Just Want to Celebrate".Image Credit: Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Rare Earth, an all-white rock band signed to Motown, in a 1971 band portrait, famous for "I Just Want to Celebrate".Image Credit: Don Paulsen/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Seeking to diversify into rock music in the late 1960s, Motown established a subsidiary label, Rare Earth, named after one of its initial signings, a Detroit-based band. While the imprint itself was short-lived, closing by the mid-1970s, Rare Earth, the band, proved to be a successful venture for Berry Gordy’s empire. Their most enduring single, “I Just Want to Celebrate,” by this all-white group, became a significant hit. This song, an anthem of positivity amidst hardship—a prevalent theme during the Vietnam War era—fused a robust funk groove with a dynamic rock-style wah-wah guitar solo and a distinctive mid-song breakdown. True to Motown’s genre-transcending spirit, “I Just Want to Celebrate” appealed to a wide audience, defying categorization. —D.B.

The Marvelettes, “Too Many Fish in the Sea” (1964)

Image Credit: James Kriegsmann/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Marvelettes projected an image of cool confidence, far from being pleading or desperate. Their hit “Too Many Fish in the Sea” evolved into a timeless feminist anthem, offering a pep talk for anyone facing romantic troubles. Gladys Horton’s vocals deliver words of wisdom: “I don’t want nobody who don’t want me/There’s too many fish in the sea!” Benny Benjamin’s drumming underscores this empowering sentiment. Penned by Motown’s acclaimed songwriters Eddie Holland and Norman Whitfield, the song resonated deeply. —R.S.

Rick James and Teena Marie, “Fire and Desire” (1981)

Rick James and Teena Marie performing together in 1997, known for their duet "Fire and Desire".Image Credit: Jim Steinfeldt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Rick James and Teena Marie performing together in 1997, known for their duet "Fire and Desire".Image Credit: Jim Steinfeldt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Rick James conceived “Fire and Desire” as a ballad inspired by a passionate affair with an Ethiopian princess. Intended as a duet with his protégé Teena Marie, plans were disrupted when Teena Marie fell ill. Despite her doctor’s advice against singing, when Rick considered a replacement, Teena Marie, as James recounts in his memoir Glow, “rose from her sickbed, stormed into the studio, and said, ‘No way I’m gonna let some other bitch sing that song.’” Despite still being feverish, Lady T delivered a vocal performance that, in Rick’s words, “folks are gonna be listening to as long as human beings are capable of love,” resulting in a legendary recording. —R.S.

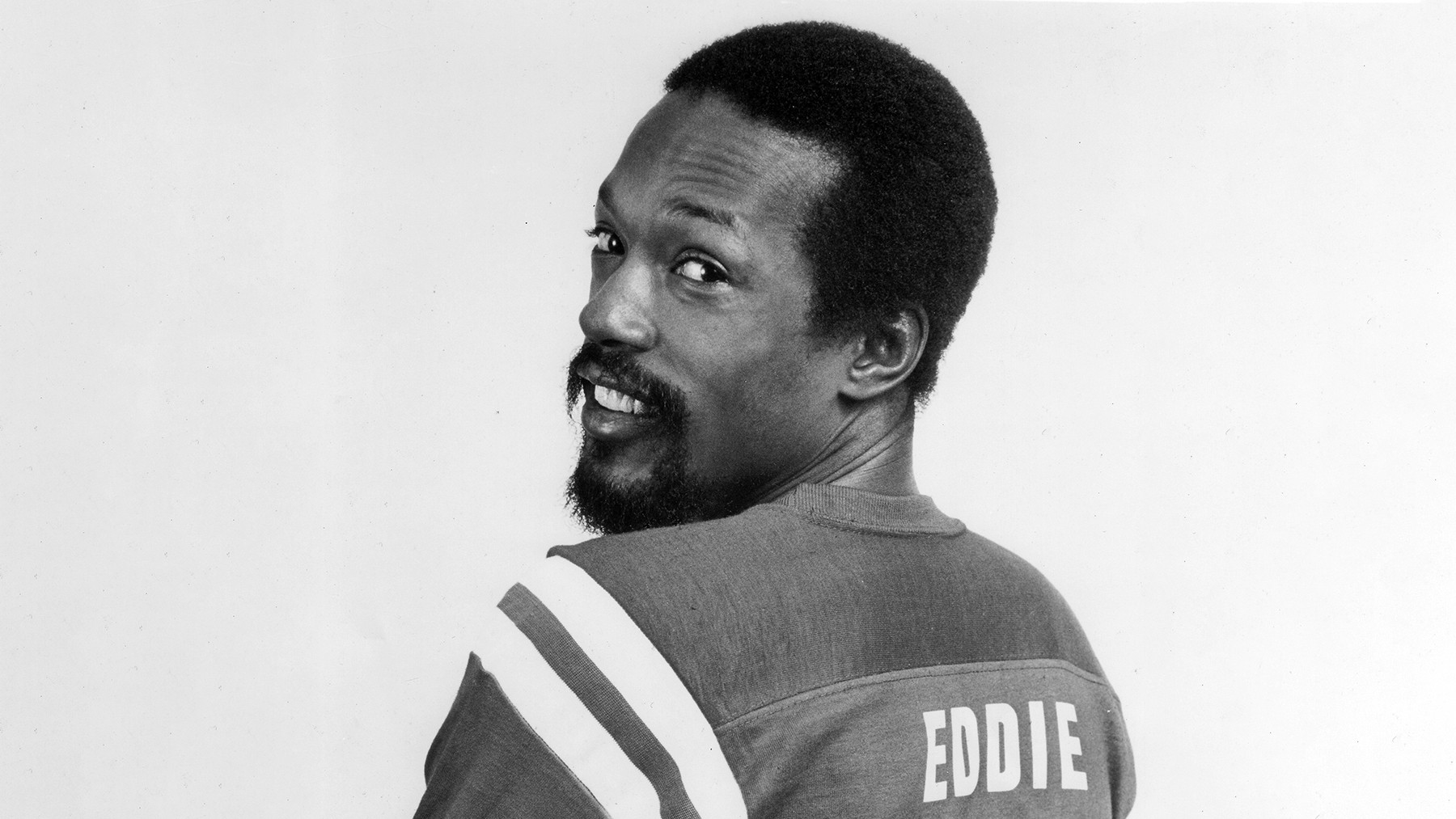

Eddie Kendricks, “Girl You Need a Change of Mind (Part 1)” (1972)

Eddie Kendricks, former member of The Temptations, in a 1970s portrait, famous for "Girl You Need a Change of Mind".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Eddie Kendricks, former member of The Temptations, in a 1970s portrait, famous for "Girl You Need a Change of Mind".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

“Girl You Need a Change of Mind” remains a dance floor staple, building momentum over several minutes before culminating in an ecstatic, wordless climax. While the instrumental arrangement has aged gracefully, the lyrical content, questioning women’s liberation (“Why march in picket lines? Burn bras and carry signs?”), reflects dated perspectives. The piano drives the track forward with heavy chords, complemented by powerful brass injections. Kendricks sustains his soaring falsetto for an impressive duration before the song transitions into a full instrumental section, leaning into a four-on-the-floor pulse that foreshadows disco. When Kendricks returns, the instrumentation drops out except for hand percussion, creating a loopable breakdown favored by DJs, making it a timeless and influential track. —E.L.

Marvin Gaye, “Trouble Man” (1972)

Marvin Gaye at the piano in the studio, circa 1974, during his "Trouble Man" era.Image Credit: Jim Britt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Marvin Gaye at the piano in the studio, circa 1974, during his "Trouble Man" era.Image Credit: Jim Britt/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The early 1970s were a golden age for blaxploitation films and their soundtracks. Following Isaac Hayes’ Shaft, Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly, and James Brown’s Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off, Marvin Gaye contributed with Trouble Man, the soundtrack for the 1972 thriller about a streetwise protagonist, Mister T. This marked Gaye’s sole venture into film soundtracks, and it was a resounding success. The bluesy theme song reached the Top 10, with Gaye’s falsetto narrating the realities of street life, encapsulating the stark truths: “There’s only three things in life that’s sure — taxes, death, and trouble.” —R.S.

The Supremes, “Up the Ladder to the Roof” (1970)

The Supremes in 1970, featuring Jean Terrell, after Diana Ross's departure, promoting "Up the Ladder to the Roof".Image Credit: Anthony Barboza/Getty Images

The Supremes in 1970, featuring Jean Terrell, after Diana Ross's departure, promoting "Up the Ladder to the Roof".Image Credit: Anthony Barboza/Getty Images

“Up the Ladder to the Roof” was recorded just two weeks after Diana Ross’s departure from The Supremes, with Jean Terrell taking over as lead singer. This song simultaneously looked to the past and the future, reminiscent of The Drifters’ 1964 classic “Up on the Roof” while incorporating elements of funky psychedelic whimsy. The result was a captivating and sweet tune that became a hit, marking their first success as The Supremes (rather than Diana Ross and the Supremes) in three years, proving their resilience and continued appeal. —J.D.

Martha and the Vandellas, “No More Tearstained Makeup” (1966)

Martha Reeves and The Vandellas performing on TV in the UK in 1967, showcasing their energy behind "No More Tearstained Makeup".Image Credit: CA/Redferns/Getty Images

Martha Reeves and The Vandellas performing on TV in the UK in 1967, showcasing their energy behind "No More Tearstained Makeup".Image Credit: CA/Redferns/Getty Images

In 1966, Smokey Robinson was at a creative peak, capable of crafting a song as flawless as “No More Tearstained Makeup” and yet modestly placing it as a B-side on a Martha and the Vandellas album. Despite never being released as a single, this track is a hidden gem for Motown aficionados. Featured on the Vandellas’ exceptional album Watchout!, its breezy rhythm is paired with Robinson’s witty lyrics, extending makeup metaphors and puns. Martha Reeves’ vocals poignantly describe “the tears pancake and powder could never cover,” adding depth to this overlooked masterpiece. —R.S.

The Four Tops, “It’s the Same Old Song” (1965)

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The story behind “It’s the Same Old Song” adds to its Motown lore. According to The Four Tops’ Duke Fakir, Lamont Dozier was tasked with quickly creating a follow-up to their hit “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie Honey Bunch)” in 1965. His solution was to reverse the chord progression of the earlier hit, resulting in the self-aware, humorous title. In just 24 hours, a new Four Tops classic was written and recorded, reaching Number Two on the R&B chart and Number Five on the pop chart. While the anecdote is compelling, the fact that The Supremes had recorded a version of “It’s the Same Old Song” a year prior adds a twist to this tale of spontaneous creation, highlighting the competitive and creative environment at Motown. —K.H.

Mary Wells, “My Guy” (1964)

Mary Wells in London in 1964, during her UK tour with The Beatles, promoting her hit "My Guy".Image Credit: Chris Ware/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Mary Wells in London in 1964, during her UK tour with The Beatles, promoting her hit "My Guy".Image Credit: Chris Ware/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Mary Wells described her signature hit, “My Guy,” as “the epitome of the Motown sound,” a fitting description. Written and produced by Smokey Robinson, the song is a delicate and feminine expression of fidelity, with Wells playfully dismissing other suitors. She revealed to biographer Peter Benjaminson that she intended the sultry outro as a humorous tribute to Mae West. “I was really joking,” she later clarified. “My Guy” became Wells’ biggest and final hit with Motown before she moved to 20th Century Fox. This song not only topped the pop charts but also established Mary Wells as Motown’s first major solo female star during the label’s formative years, defining early Motown’s crossover appeal. —B.S.

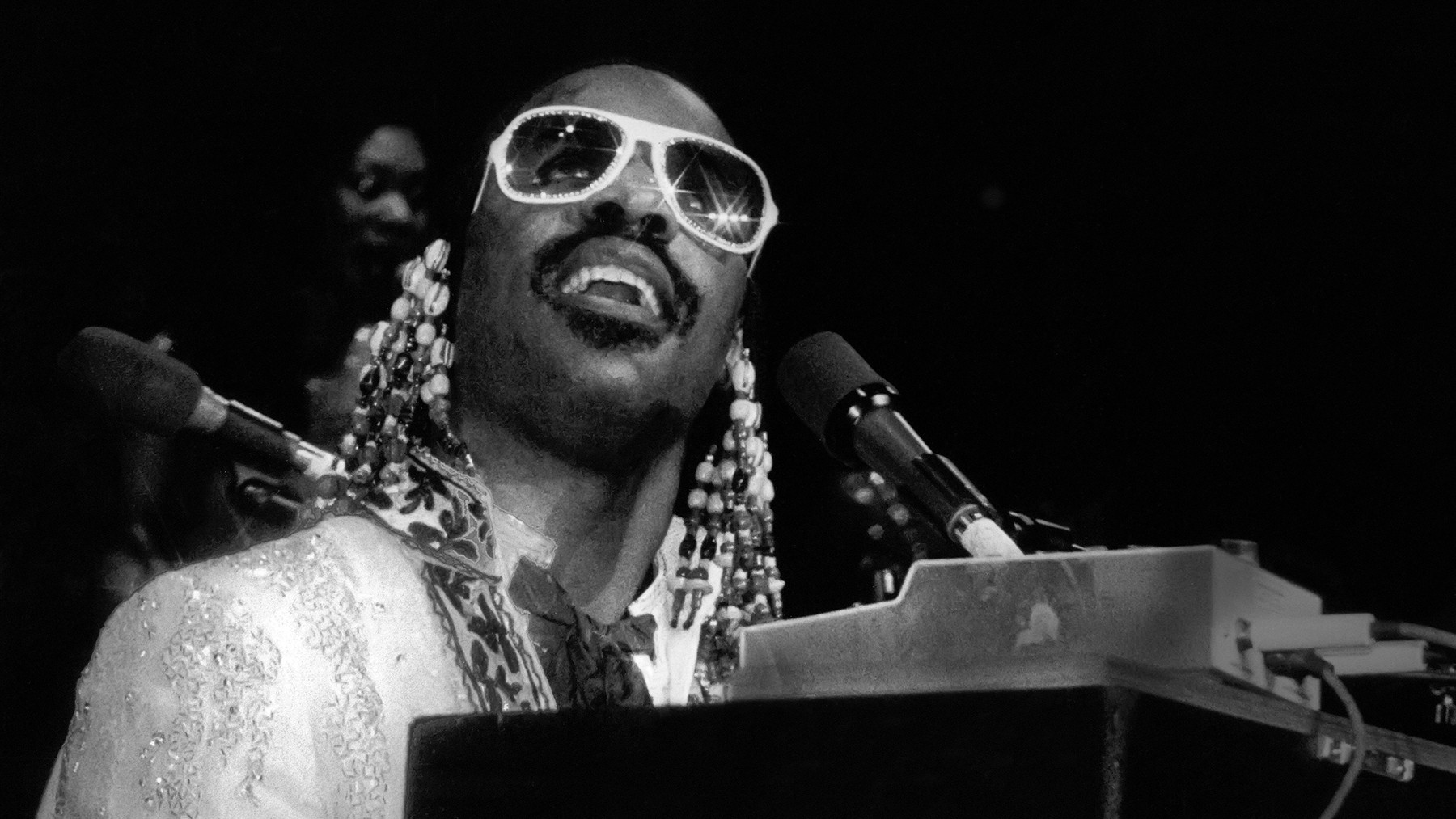

Stevie Wonder, “Sir Duke” (1977)

Stevie Wonder performing in 1976, around the release of "Songs in the Key of Life" featuring "Sir Duke".Image Credit: PL Gould/IMAGES/Getty Images

Stevie Wonder performing in 1976, around the release of "Songs in the Key of Life" featuring "Sir Duke".Image Credit: PL Gould/IMAGES/Getty Images

“Sir Duke” is an irresistible invitation to joy. Its vibrant Lindy-Hop-inspired horns, funky bassline, playful slide-whistle, and Stevie Wonder’s warm vocals practically compel listeners to smile and “feel it all over.” For Wonder, this track was a heartfelt homage to musical icons Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, and Duke Ellington himself. He explained, “[I] wanted it to be about the musicians who did something for us.” Ultimately, “Sir Duke” transcends a personal tribute, evolving into an uplifting celebration of music’s unifying power, offering “equal opportunity for all to sing, dance, and clap their hands.” Indeed, Wonder’s creation of “Sir Duke” is itself worthy of tribute. —K.G.

Boyz II Men, “End of the Road” (1992)

Boyz II Men in a 1990s portrait, known for their record-breaking hit "End of the Road".Image Credit: Michel Linssen/Redferns/Getty Images

Boyz II Men in a 1990s portrait, known for their record-breaking hit "End of the Road".Image Credit: Michel Linssen/Redferns/Getty Images

While Motown’s classic era had long passed by the 1990s, the label’s most commercially successful hit was still to come. “End of the Road” originated from songwriters Kenneth “Babyface” Edmonds and Daryl Simmons’ reflections on their divorces, with additional input from L.A. Reid. This song, with its smooth harmonies and Michael McCary’s Barry White-esque spoken interlude, bridged classic Motown vocal traditions with contemporary R&B sensibilities. “End of the Road” dominated the charts for 13 weeks at Number One, surpassing Elvis Presley’s long-standing record set by “Don’t Be Cruel”/”Hound Dog,” marking a significant milestone for Motown in a new era. —K.H.

Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, “Going to a Go-Go” (1965)

Image Credit: Cyrus Andrews/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The title track from The Miracles’ seminal 1965 album, Going to a Go-Go, is both an invitation to a night out and a metaphor for Motown’s inclusive and integrationist ethos. Smokey Robinson’s lyrics, “You might see anyone in town,” capture this spirit of community and openness. The driving beat from the Funk Brothers elevates this song to the ranks of Motown’s great anthems of joy, aspiration, and togetherness, alongside tracks like “Dancing in the Street.” It encapsulates the energy and optimism of the era and Motown’s role within it. —J.D.

The Temptations, “Cloud Nine” (1968)

The Temptations performing in concert at Madison Square Garden, 1969, during their psychedelic soul era with "Cloud Nine".Image Credit: Walter Iooss Jr./Getty Images

The Temptations performing in concert at Madison Square Garden, 1969, during their psychedelic soul era with "Cloud Nine".Image Credit: Walter Iooss Jr./Getty Images

When Holland, Dozier, and Holland departed Motown, songwriter-producers Barrett Strong and Norman Whitfield stepped in, steering the label towards new sonic territories. “Cloud Nine” was the first of The Temptations’ psychedelic-influenced singles, drawing inspiration from Sly and the Family Stone’s groundbreaking fusion of soul and rock. While some, including Berry Gordy, interpreted the song as having drug references, Temptations member Otis Williams clarified, “I know there weren’t drug references because Norman and Barrett didn’t do drugs.” Regardless of interpretation, “Cloud Nine” marked a significant evolution in The Temptations’ sound and Motown’s broader musical direction. —J.D.

Diana Ross and the Supremes, “Someday We’ll Be Together” (1969)

Image Credit: PA Images/Getty Images

Ironically, Diana Ross’s final single with The Supremes, “Someday We’ll Be Together,” was not a true group effort. Neither Mary Wilson nor Cindy Birdsong participated in the recording, their parts taken by session singers Maxine and Julia Waters. Despite this unusual circumstance, the elegantly crafted record, co-written by Johnny Bristol, who also provides background vocals, stands as one of the most majestic and poignant songs of the Motown era. As the last Number One hit of the 1960s, it served as a fitting farewell to both the group’s original lineup and the decade that had propelled them to stardom. —D.B.

Stevie Wonder, “Boogie On Reggae Woman” (1974)

Stevie Wonder in a 1970s portrait, during his innovative period including "Boogie On Reggae Woman".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Stevie Wonder in a 1970s portrait, during his innovative period including "Boogie On Reggae Woman".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In 1974, reggae was beginning to gain traction in the U.S., and Stevie Wonder, characteristically ahead of the curve, propelled it into the Top Ten with “Boogie On Reggae Woman.” This track is a synth-funk, electro-reggae fusion where Wonder plays almost all instruments himself, from the harmonica solo to the distinctive Moog bass line. He also adds playful lyrics, “I’d like to see you in the raw under the stars above.” Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead was a notable admirer, frequently performing extended jams of “Boogie On Reggae Woman” live, sometimes stretching to 17 or 18 minutes, highlighting its improvisational and cross-genre appeal. —R.S.

The Undisputed Truth, “Smiling Faces Sometimes” (1971)

The Undisputed Truth, a Motown trio known for "Smiling Faces Sometimes", in a 1970s portrait.Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Undisputed Truth, a Motown trio known for "Smiling Faces Sometimes", in a 1970s portrait.Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong initially wrote “Smiling Faces Sometimes,” a cautionary tale about deceitful appearances, for The Temptations, who recorded it in 1971. However, it was Motown trio The Undisputed Truth who transformed the original 12-minute jam into a concise, impactful three-minute soul track. They slowed down the tempo, added horns, and created a foreboding atmosphere far removed from the typical carefree romance themes of 1960s Motown. The lyrics warn against “smiling faces” that “pretend to be your friend” but “don’t tell the truth.” While The Undisputed Truth didn’t achieve consistent mainstream success, “Smiling Faces Sometimes” became their signature song and was notably covered by artists ranging from Rare Earth to Joan Osborne, attesting to its enduring message and musical power. —J.N.

The Supremes, “My World Is Empty Without You” (1965)

The Supremes in 1965, featuring Diana Ross, Florence Ballard, and Mary Wilson, promoting "My World Is Empty Without You".Image Credit: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

The Supremes in 1965, featuring Diana Ross, Florence Ballard, and Mary Wilson, promoting "My World Is Empty Without You".Image Credit: Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

“My World Is Empty Without You” is characterized by one of Motown’s most compelling and obsessive rhythms. Diana Ross’s vocals convey loneliness and isolation, but the true emotional depth lies in the rhythm, largely driven by drum master Benny Benjamin. Stevie Wonder, in a 1973 interview with Rolling Stone, praised Benjamin as “one of the major forces in the Motown sound,” citing tracks like “Can’t Help Myself,” “My World Is Empty Without You, Babe,” “This Old Heart of Mine,” “Don’t Mess With Bill,” and “Girl’s All Right With Me” as prime examples of Benjamin’s impactful drumming, which just “pop!” —R.S.

Stevie Wonder, “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” (1974)

Stevie Wonder performing live in 1974, the year "You Haven't Done Nothin'" was released.Image Credit: Getty Images

Stevie Wonder performing live in 1974, the year "You Haven't Done Nothin'" was released.Image Credit: Getty Images

Released shortly after Nixon’s resignation in 1974, “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” is a fiercely funky and politically charged track, almost a weaponized version of “Superstition.” Stevie Wonder’s clavinet performance is particularly aggressive, complemented by defiant and celebratory backing vocals from The Jackson 5. Reflecting the public sentiment, the song topped both R&B and pop charts. While addressing the ongoing struggle against powerful figures, “You Haven’t Done Nothin’” also showcased musical innovation, integrating synthesizers and the then-novel drum machine, pointing towards future sounds. —K.H.

Brenda Holloway, “Every Little Bit Hurts” (1964)

Brenda Holloway in a 1960s portrait, known for her soulful rendition of "Every Little Bit Hurts".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Brenda Holloway in a 1960s portrait, known for her soulful rendition of "Every Little Bit Hurts".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Brenda Holloway, with her gospel and classical music background, brought a distinct old-soul weariness to Motown, setting her apart from the label’s typically youthful exuberance. This was especially evident in “Every Little Bit Hurts,” a profoundly mournful ballad. Initially reluctant to record the song, Holloway’s subdued tension is palpable in her delivery, adding to the song’s poignant vulnerability. “Every Little Bit Hurts” became the first in a series of heartbroken hits for Holloway, resonating deeply and inspiring covers by artists across genres, including Aretha Franklin and The Clash, highlighting its universal emotional appeal. —J.D.

The Jackson 5, “The Love You Save” (1970)

The Jackson 5 in 1970, promoting their string of hits including "The Love You Save".Image Credit: Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

The Jackson 5 in 1970, promoting their string of hits including "The Love You Save".Image Credit: Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

From its Sly and the Family Stone-esque groove to lyrics advising a flirtatious partner to “take it slow/or someday you’ll be all alone,” The Jackson 5’s third consecutive Number One hit, “The Love You Save,” signaled a move towards more mature themes compared to their earlier bubblegum pop hits like “I Want You Back” and “ABC.” Leading this evolution was Michael Jackson. Despite being only 11 years old, his voice conveyed such intensity and passion that he sounded convincingly like a heartbroken adult, demonstrating his exceptional talent and range even at a young age. —D.B.

The Supremes, “Bad Weather” (1973)

The Supremes in the early 1970s with Jean Terrell, continuing their hit streak with songs like "Bad Weather".Image Credit: Tony Russell/Redferns/Getty Images

The Supremes in the early 1970s with Jean Terrell, continuing their hit streak with songs like "Bad Weather".Image Credit: Tony Russell/Redferns/Getty Images

After Diana Ross embarked on her solo career, many predicted the end of The Supremes. However, with Jean Terrell as the new lead singer, the group defied expectations and continued to produce hits. “Bad Weather,” though somewhat overlooked today, is a prime example of early 1970s sad-girl funk, imbued with a rainy-day mood. Written by Stevie Wonder, the song draws inspiration from the Memphis soul sound of Al Green and Willie Mitchell, evident in its sweet-and-sour horns and jazz-influenced chords. “Bad Weather” makes a strong case for the 1970s Supremes being as compelling as their 1960s iteration, showcasing their adaptability and enduring musicality. —R.S.

Teena Marie, “Square Biz” (1980)

Teena Marie performing in 1985, known for her funk hit "Square Biz" featuring rap elements.Image Credit: Sherry Rayn Barnett /Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Teena Marie performing in 1985, known for her funk hit "Square Biz" featuring rap elements.Image Credit: Sherry Rayn Barnett /Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The emergence of hip-hop into mainstream consciousness began with The Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” in early 1980. Teena Marie was among the artists who recognized this shift, incorporating a playful rap interlude into her 1981 hit “Square Biz”: “I’m less than five foot one, a hundred pounds of fun/I like sophisticated funk/I live on Dom Perignon, caviar, filet mignon/And you can best believe that’s bunk.” This whimsical boastfulness enhances the festive atmosphere of “Square Biz,” a high-energy funk track with prominent, popping bass and intricate horn arrangements. Even a bizarre, robotic-voiced digression can’t detract from the song’s infectious energy and innovative blend of funk and early rap elements. —E.L.

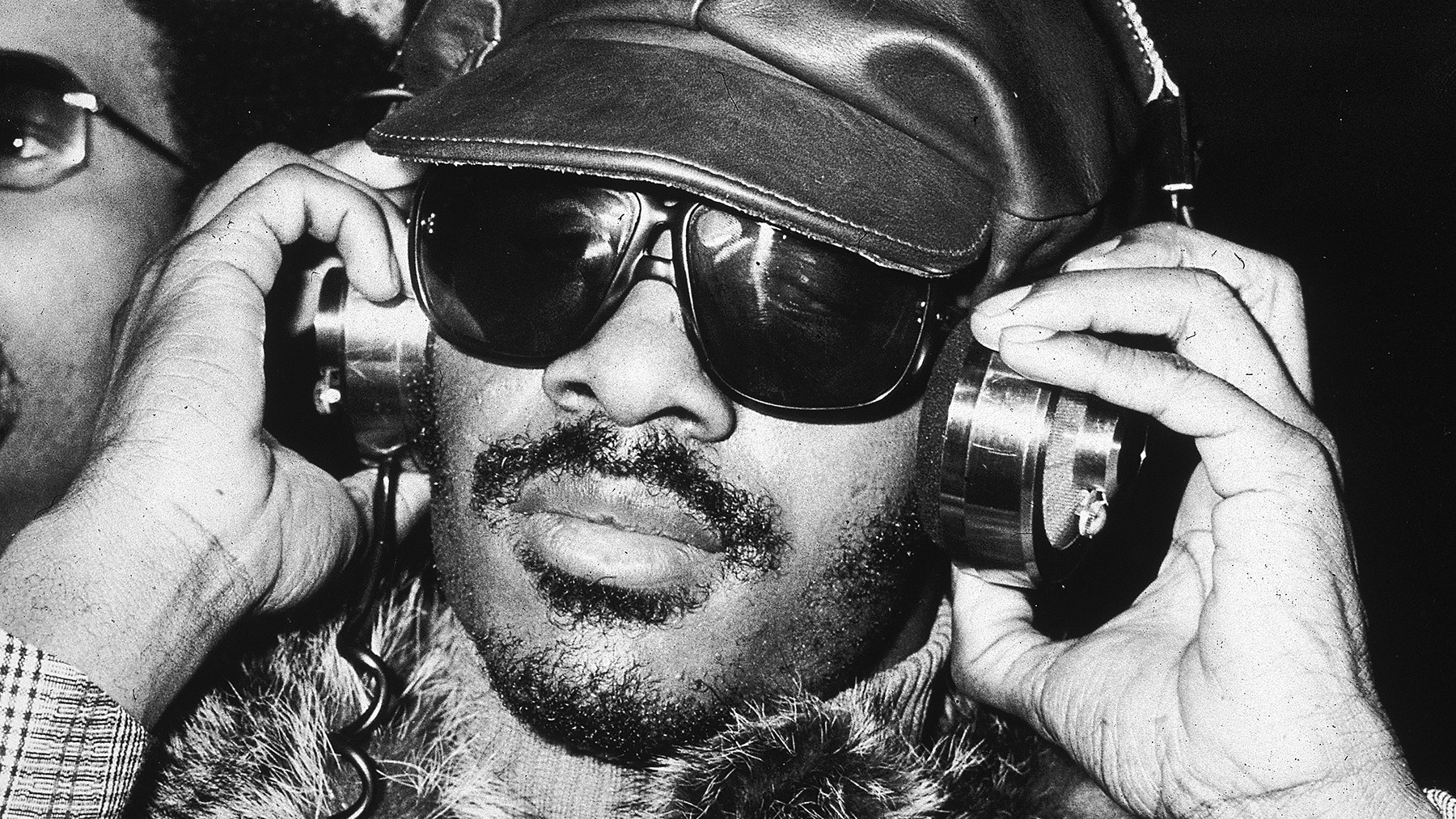

Stevie Wonder, “My Cherie Amour” (1969)

Stevie Wonder in London, 1966, during the early phase of his career, before the release of "My Cherie Amour".Image Credit: PA Images via Getty Images

Stevie Wonder in London, 1966, during the early phase of his career, before the release of "My Cherie Amour".Image Credit: PA Images via Getty Images

It’s a delightful challenge to decide what’s more uplifting in “My Cherie Amour”: the opening horns or Stevie Wonder’s la la la’s. Together, they create a quintessential sunshine-soul pop sound that is distinctly 1969. Originally titled “Oh, My Marsha” after Wonder’s girlfriend, the track is famously featured in the movie Almost Famous, during the poignant scene where Penny Lane overdoses. The song’s upbeat tempo ironically underscores the gravity of the moment as her heels slip on the marble floor, juxtaposed with the euphoric horns, creating a memorable and emotionally resonant cinematic moment. —A.M.

Diana Ross and the Supremes, “Love Child” (1968)

Image Credit: Silver Screen Collection/Getty Images

“Love Child” was recorded as Diana Ross was on the cusp of solo stardom. It was effectively a solo single in all but name, being one of the first Supremes recordings without the other Supremes participating. In this track, a step towards more mature soul territory, Ross narrates the story of a child born out of wedlock, grappling with social stigma and personal shame. However, the production by The Clan, with its funky guitar, sentimental strings, and chimes, softens the potentially somber theme. Ross’s inherent grace transforms the narrative into something compelling and distinct, highlighting her unique ability to blend sophistication with emotional depth. —K.G.

The Commodores, “Easy” (1977)

Lionel Richie with The Commodores in a 1970s portrait, during their soft rock and ballad era with "Easy".Image Credit: Echoes/Redferns/Getty Images

Lionel Richie with The Commodores in a 1970s portrait, during their soft rock and ballad era with "Easy".Image Credit: Echoes/Redferns/Getty Images

Is there a gentler breakup song than “Easy”? Lionel Richie acknowledges it “sounds funny,” yet his departure is accompanied by a mellow piano groove, almost lulling his lover back to sleep. His desire for freedom and peace is palpable, and who could deny such a tender farewell? Richie once described the song’s feeling as “Easy like Sunday morning,” relatable to anyone from a small Southern town. He drew from his own experiences growing up in Tuskegee, Alabama, where, as he noted, “there is no such thing as four-in-the-morning partying,” capturing a serene and reflective mood. —K.G.

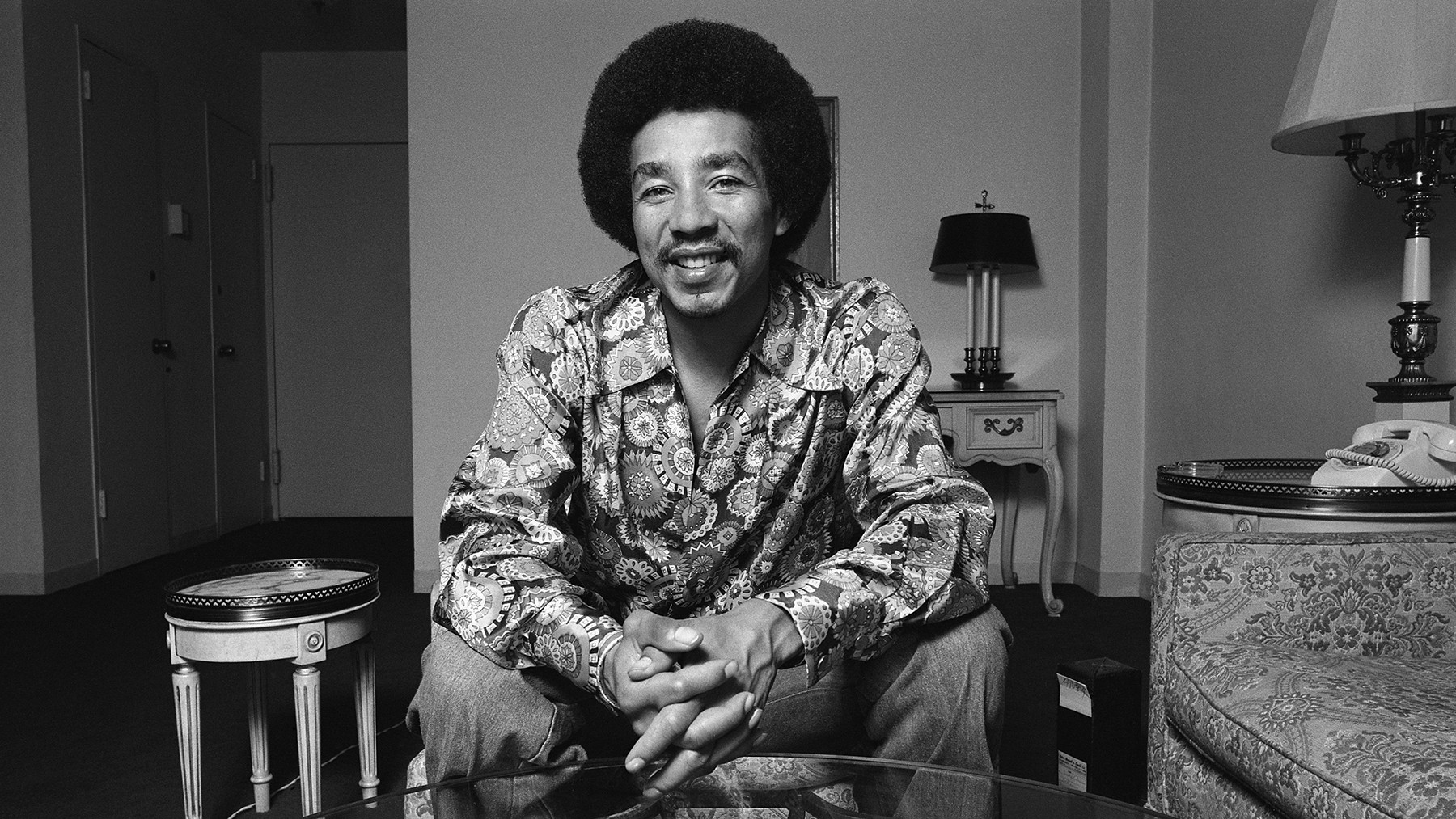

Smokey Robinson, “Quiet Storm” (1975)

Smokey Robinson in a 1970s portrait, during his "Quiet Storm" solo era.Image Credit: Leonard M. DeLessio/Corbis/Getty Images

Smokey Robinson in a 1970s portrait, during his "Quiet Storm" solo era.Image Credit: Leonard M. DeLessio/Corbis/Getty Images

In Motown’s narrative, Smokey Robinson is celebrated for his poignant work with The Miracles and his songwriting and production for artists like Mary Wells and The Temptations. However, discussions of Motown in the 1970s often spotlight Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, sometimes overshadowing Robinson’s contributions. This is unfortunate, as Robinson’s 1970s output is often captivating, particularly Quiet Storm, an album that lent its name to an entire genre of smooth, sophisticated R&B. The title track unfolds over nearly eight minutes, featuring ethereal synthesizer sounds, wind effects, and a delicate flute solo over a subtle rhythm section. In this tranquil setting, Robinson’s romantic desires are vividly expressed: “You short-circuit all my nerves, promising electric things/You touch me and suddenly there’s rainbow rings,” showcasing his enduring artistry. —E.L.

The Four Tops, “Bernadette” (1967)

The Four Tops in a promotional shot, known for their dramatic hit "Bernadette".Image Credit: AP

The Four Tops in a promotional shot, known for their dramatic hit "Bernadette".Image Credit: AP

Poor Bernadette seems destined to fall short of Levi Stubbs’s idealized vision in “Bernadette.” Within three minutes, Stubbs declares, “I live only to hold you,” “I need you to live,” and escalates to “You’re the soul of me, more than a dream, you’re a plan to me.” While Stubbs’s intensity might border on unsettling at times, particularly when the music darkens as he proclaims “You belong to me,” there is also something undeniably endearing in his devotion. Like all great Four Tops singles, the chorus is irresistibly captivating. Who wouldn’t want to be loved with such fervor? K.G.

Marvin Gaye, “Can I Get a Witness” (1963)

Marvin Gaye in 1963, early in his Motown career, around the release of "Can I Get a Witness".Image Credit: David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images

Marvin Gaye in 1963, early in his Motown career, around the release of "Can I Get a Witness".Image Credit: David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images

With its boogie-woogie piano and gospel-infused lyrics that blurred the line between sacred and secular, “Can I Get a Witness” arguably marked Marvin Gaye’s first true classic hit in September 1963. In classic Motown style, the recording was a family affair, with The Supremes contributing background vocals. The Supremes later recorded their own version, though unreleased until 1987. “Can I Get a Witness” significantly influenced British soul fans; The Rolling Stones included a version on their debut album and created an instrumental response track, “Now, I’ve Got a Witness.” Dusty Springfield also delivered a powerful rendition in 1964, highlighting the song’s wide appeal and influence. —J.D.

The Temptations, “Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today)” (1970)

The Temptations in a 1970s promotional photo, reflecting the era of "Ball of Confusion".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Temptations in a 1970s promotional photo, reflecting the era of "Ball of Confusion".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Temptations’ Otis Williams described the potent impact of “Ball of Confusion”: “When I heard the groove to that I thought, ‘Man, that’s got to be funkier than unwashed armpits,’ ‘cause it had the funk on it, it had the stink.” The Temptations addressed a wide range of social and political issues in “Ball of Confusion,” from segregation to rapid youth maturation, unemployment, taxation, and financial burdens. Songwriters Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong crafted a track as sharp and explosive as the lyrics, capturing the tumultuous spirit of the times. —J.D.

Marvin Gaye, “I Want You” (1976)

Marvin Gaye in a studio session in the 1970s, during the making of his "I Want You" album.Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Marvin Gaye in a studio session in the 1970s, during the making of his "I Want You" album.Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Marvin Gaye’s early 1970s albums often receive more acclaim, but 1976’s I Want You is remarkably ambitious and deeply groovy, particularly its title track. Gaye layers multi-tracked backing vocals throughout the song, sometimes echoing the lead, sometimes interjecting with ad-libs, all unified by lush “ooohs” and “aaahs.” Just as the four-minute track begins to fade, it leaves the listener wanting more. For those cravings, a John Morales extended mix of “I Want You” doubles the length, emphasizing the interplay of instruments and allowing listeners to immerse themselves in its mesmerizing groove for nearly ten minutes. —E.L.

Mary Jane Girls, “All Night Long” (1983)

The Mary Jane Girls in June 1983, promoting their funk hit "All Night Long".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Mary Jane Girls in June 1983, promoting their funk hit "All Night Long".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The foundation of “All Night Long” is undeniably compelling—a sparse bassline over a dry, echoing snare drum. It seems to draw inspiration from Keni Burke’s “Risin’ to the Top,” released the previous year, particularly in the snare’s impactful sound. This rhythmic DNA then influenced tracks like Maxwell’s “Ascension (Don’t Ever Wonder)” in the 1990s and was directly sampled by Groove Theory and Mary J. Blige, among others. The rhythm track is so strong it could support any lyrics and still be a hit. The Mary Jane Girls elevate it with suggestive lyrics about a late-night rendezvous, turning rhythmic brilliance into lyrical allure. —E.L.

Diana Ross, “Love Hangover” (1976)

Diana Ross performing in 1976, the year of her disco hit "Love Hangover".Image Credit: Suzanne Vlamis/AP

Diana Ross performing in 1976, the year of her disco hit "Love Hangover".Image Credit: Suzanne Vlamis/AP

Diana Ross masterfully employs a tempo shift in “Love Hangover” to create a dance floor sensation, transitioning from a sultry, slow funk to energetic disco. Producer Hal David reportedly enhanced the recording sessions with liquor, offering Rémy Martin to band members and vodka to Ross, according to The Billboard Book of Number One R&B Hits. “Love Hangover” became a Number One hit in 1976, foreshadowing Ross’s successful foray into disco with her 1980 album Diana. As Ross herself declared about the song’s intoxicating effect, “if there’s a cure for this, I don’t want it.” —E.L.

The Commodores, “Brick House” (1977)

Lionel Richie and The Commodores in a 1970s group portrait, known for funk hits like "Brick House".Image Credit: Echoes/Redferns/Getty Images

Lionel Richie and The Commodores in a 1970s group portrait, known for funk hits like "Brick House".Image Credit: Echoes/Redferns/Getty Images

The Commodores were known for many qualities, but subtlety wasn’t among them. Following “Young Girls Are My Weakness,” they delivered “Brick House,” an ode to a woman “built like an Amazon.” Lionel Richie explained, “A brick house means she’s stacked… She’s built like a brick shithouse means that she’s strong.” Like Kool and the Gang’s “Celebration,” “Brick House” has become a cultural phenomenon, transcending its funk origins to become a cross-generational anthem. Over four decades after its release, it remains a universally recognized and celebrated track, its appeal undiminished. —J.N.

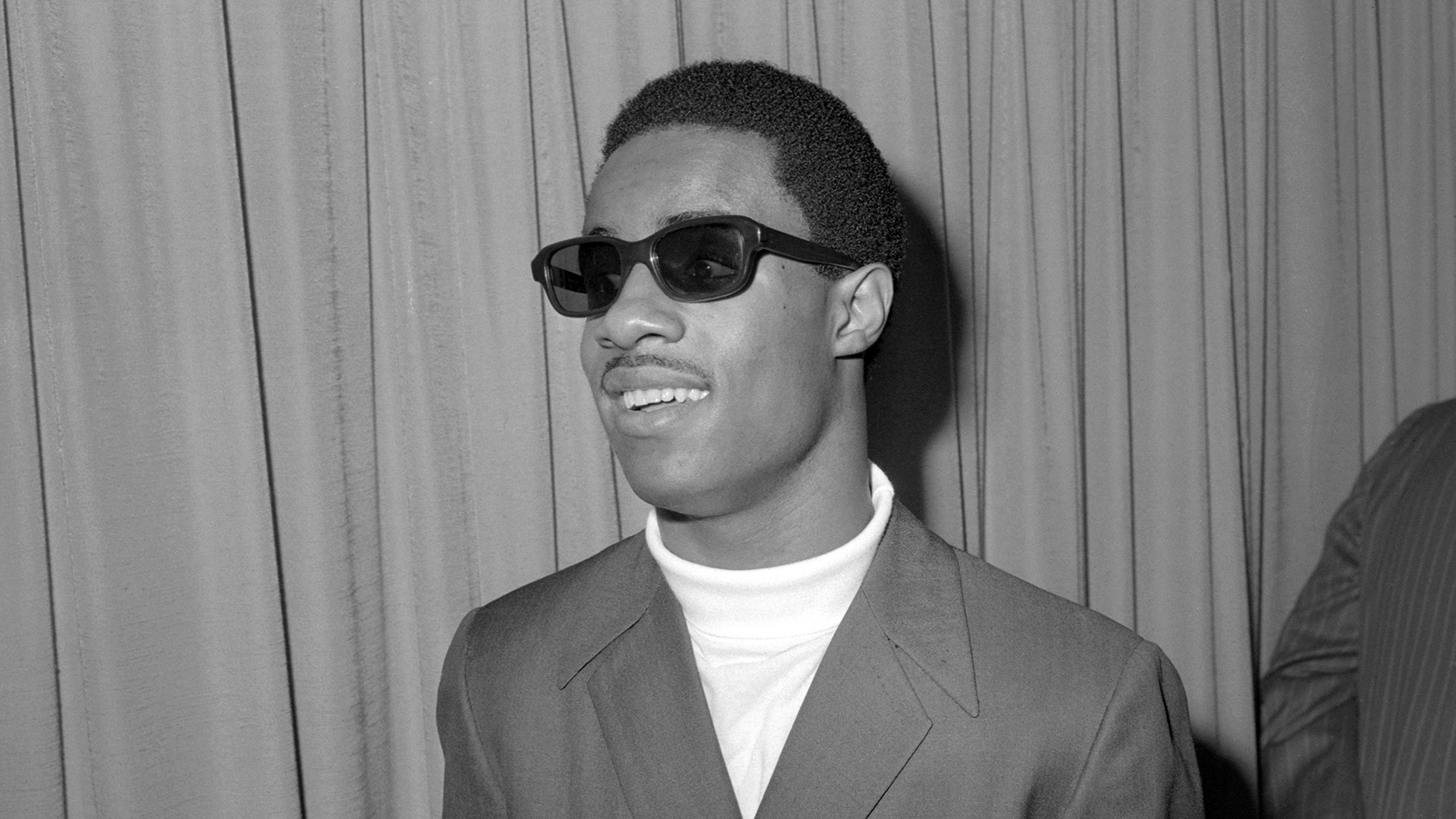

Stevie Wonder, “Uptight (Everything’s Alright)” (1965)

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In 1965, amidst Stevie Wonder’s changing voice and a lull in chart success, some speculated that the teenage prodigy’s career might be fading. However, he returned from a European tour with “Uptight (Everything’s Alright),” a dynamic track influenced by The Rolling Stones. Sylvia Moy and Henry Crosby refined the lyrics, as Moy, lacking a Braille version, sang them line by line to Wonder during recording. “Uptight” became a Number Three pop hit and Wonder’s first single to top the R&B charts, proving his enduring talent and marking just the beginning of his extraordinary career. —K.H.

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell, “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” (1967)

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell in a 1967 portrait, iconic for their duets including "Ain't No Mountain High Enough".Image Credit: Redferns

Marvin Gaye and Tammi Terrell in a 1967 portrait, iconic for their duets including "Ain't No Mountain High Enough".Image Credit: Redferns

Ashford and Simpson recognized the hit potential of “Ain’t No Mountain High Enough” immediately. Simpson recalled, “Nick called it the ‘golden egg.’” Despite interest from Dusty Springfield, they reserved it for their Motown opportunity. Arriving at the studio with charts and a production plan, they still allowed for improvisation. The distinctive “tick-a-tick-a-tick” sound is attributed to drummer Uriel Jones hitting the metal rim of his snare drum, a spontaneous element that became integral to the song’s iconic rhythm. —K.H.

Thelma Houston, “Don’t Leave Me This Way” (1976)

Thelma Houston in a 1970s portrait, known for her disco version of "Don't Leave Me This Way".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Thelma Houston in a 1970s portrait, known for her disco version of "Don't Leave Me This Way".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Originally recorded by Harold Melvin and the Blue Notes in 1975, Thelma Houston covered “Don’t Leave Me This Way” for her 1976 album, Any Way You Like It. Prior to this, Houston had struggled to achieve chart success, and this disco rendition was initially intended for Diana Ross. Fortunately, Houston’s passionate performance resonated widely, becoming a disco staple and earning her a Grammy Award. Over time, “Don’t Leave Me This Way” gained deeper significance, evolving into a poignant anthem during the HIV/AIDS epidemic, underscoring its emotional depth and lasting impact. —B.S.

The Spinners, “It’s a Shame” (1970)

The Spinners in a 1970s portrait, known for their hit "It's a Shame" co-written by Stevie Wonder.Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

The Spinners in a 1970s portrait, known for their hit "It's a Shame" co-written by Stevie Wonder.Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

In 1970, The Spinners, a renowned Motown vocal group, had been absent from the charts for four years. Their resurgence came with “It’s a Shame,” co-written by Stevie Wonder and Syreeta Wright, which became their biggest hit. The song features dynamic funk riffs over proto-boom bap drums, as lead singer G.C. Cameron transitions from smooth crooning to a bemused falsetto and finally to the passionate outcry of a jilted lover within three minutes. By the time Cameron belts, “Why don’t you free me, from this prison/Where I serve my time as your fool,” the listener is moved to offer sympathy and perhaps suggest The Marvelettes’ empowering “Too Many Fish in the Sea” as a remedy for heartbreak. —J.N.

Marvin Gaye, “Ain’t That Peculiar” (1965)

Marvin Gaye in a mid-1960s portrait, during the peak of his early Motown hits like "Ain't That Peculiar".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Marvin Gaye in a mid-1960s portrait, during the peak of his early Motown hits like "Ain't That Peculiar".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Following Smokey Robinson’s success in writing Marvin Gaye’s first Number 1 R&B hit, “I’ll Be Doggone,” Motown’s standard practice was for Robinson to produce the follow-up. He did, enlisting fellow Miracles, particularly Marv Tarplin, who created the central guitar riff of “Ain’t That Peculiar.” Enhanced by backing vocals from The Adantes and showcasing Gaye’s ability to ride a groove and deliver a powerful chorus, “Ain’t That Peculiar” reached Number One on the R&B Singles chart and the Top 10 on the Pop Singles chart in 1965, cementing Gaye’s status as a major Motown artist. —K.H.

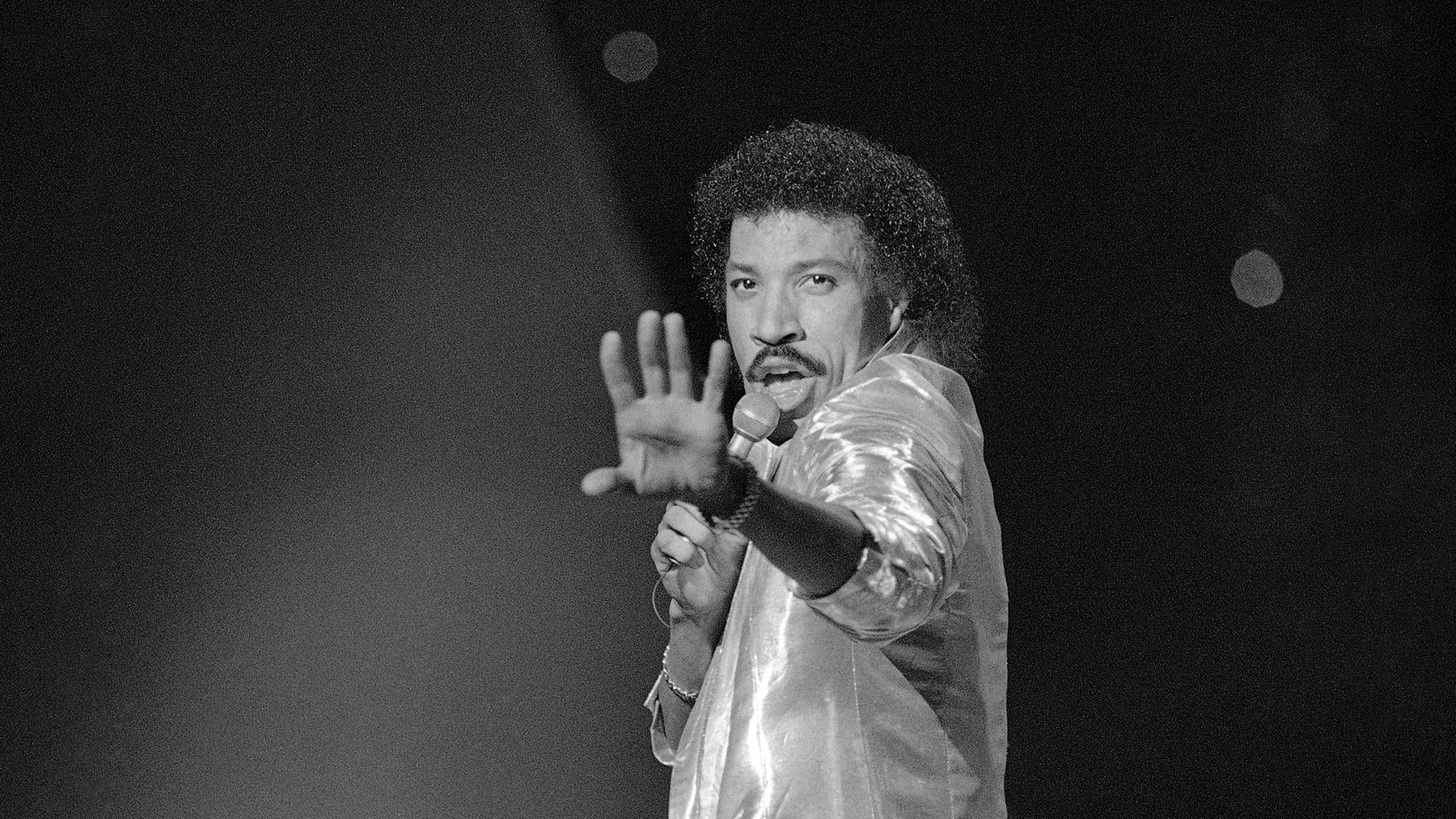

Lionel Richie, “All Night Long (All Night)” (1983)

Lionel Richie performing at the American Music Awards in 1985, after the massive success of "All Night Long".Image Credit: Doug Pizac/AP

Lionel Richie performing at the American Music Awards in 1985, after the massive success of "All Night Long".Image Credit: Doug Pizac/AP

“All Night Long (All Night),” a buoyant party anthem, soared to Number One in 1983, making Lionel Richie a global pop superstar. Recorded with James Anthony Carmichael and session musicians, some of whom had worked on Thriller, the song features a lush, Caribbean-influenced groove. Its international appeal is enhanced by phrases in Caribbean patois, Spanish, and Swahili. For the song’s breakdown, Richie sought African phrases from a UN contact, but when that proved time-consuming, he improvised the interjections himself, contributing to the song’s spontaneous and globally inclusive vibe. —C.H.

The Supremes, “Come See About Me” (1964)

Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

With its cheerful melody, inviting title hook, and energetic beat, The Supremes’ third Number One hit, “Come See About Me,” exemplifies hiding heartbreak within a vibrant package. Diana Ross sings of intense longing, isolating herself from friends in anticipation of a lover’s return that seems unlikely. They performed the song on their first of 19 appearances on The Ed Sullivan Show. Mary Wilson recalled their debut, noting Ed Sullivan’s casual introduction: “He didn’t know our names. He’d just say, ‘And here they are, the … the … the girls!’” marking their entry into mainstream America. —J.D.

The Temptations, “Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me)” (1971)

The Temptations in the early 1970s, during their soft soul era with "Just My Imagination".Image Credit: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The Temptations in the early 1970s, during their soft soul era with "Just My Imagination".Image Credit: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Following The Temptations’ shift towards funkier, harder-edged tracks like “Psychedelic Shack” and “Ball of Confusion,” “Just My Imagination” offered a nostalgic return to their classic sound. With tremulous strings from the Detroit Symphony Orchestra and The Temptations’ smooth harmonies, lead singer Eddie Kendricks daydreams about a romance with a seemingly unattainable neighbor. The song poignantly captures the bittersweet nature of fantasy versus reality: “it’s just my imagination running away from me.” Kendricks’ vocal performance is exceptional—Otis Williams recalls his dedication to perfecting it—but ironically, by the time “Just My Imagination” reached Number One, Kendricks, frustrated with the group, had already left, marking a bittersweet success. —K.G.

The Marvelettes, “The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game” (1967)

Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

“The Hunter Gets Captured by the Game” by The Marvelettes cleverly uses metaphors of pursuit and capture in romance. “Secretly I been tailing you, like a fox that preys on a rabbit,” Wanda Young sings, detailing a romantic strategy turned on its head. Penned by Smokey Robinson, the lyrics use consistently metaphorical language, even describing love as “a sudden slap.” Yet, Young’s vocals remain serenely untroubled, and the music is light and swinging with bright strings, suggesting a happy resolution where hunter and prey find harmony, blending playful lyrics with sophisticated musicality. —E.L.

Jr. Walker and the All Stars, “Shotgun” (1965)

Jr. Walker and The All Stars in a 1960s group portrait, known for their instrumental hit "Shotgun".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Jr. Walker and The All Stars in a 1960s group portrait, known for their instrumental hit "Shotgun".Image Credit: Gilles Petard/Redferns/Getty Images

Jr. Walker’s inspiration for “Shotgun” came from observing dancers at the El Grotto Club in Battle Creek, Michigan, playfully mimicking shooting with their fingers as they danced. This visual translated into a musical explosion of hiccuping drum fills, organ bursts, and Walker’s dynamic saxophone, which darts and weaves like someone dodging gunfire with style. (The initial “bang” sound is famously guitarist Eddie Willis accidentally kicking his amplifier). The All Stars lock into a groove, demonstrating how much can be achieved with just one chord. “Shotgun” hit Number One on the R&B chart and reached the Top 10 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 1965, becoming an instrumental classic and a testament to raw energy and rhythm. —K.H.

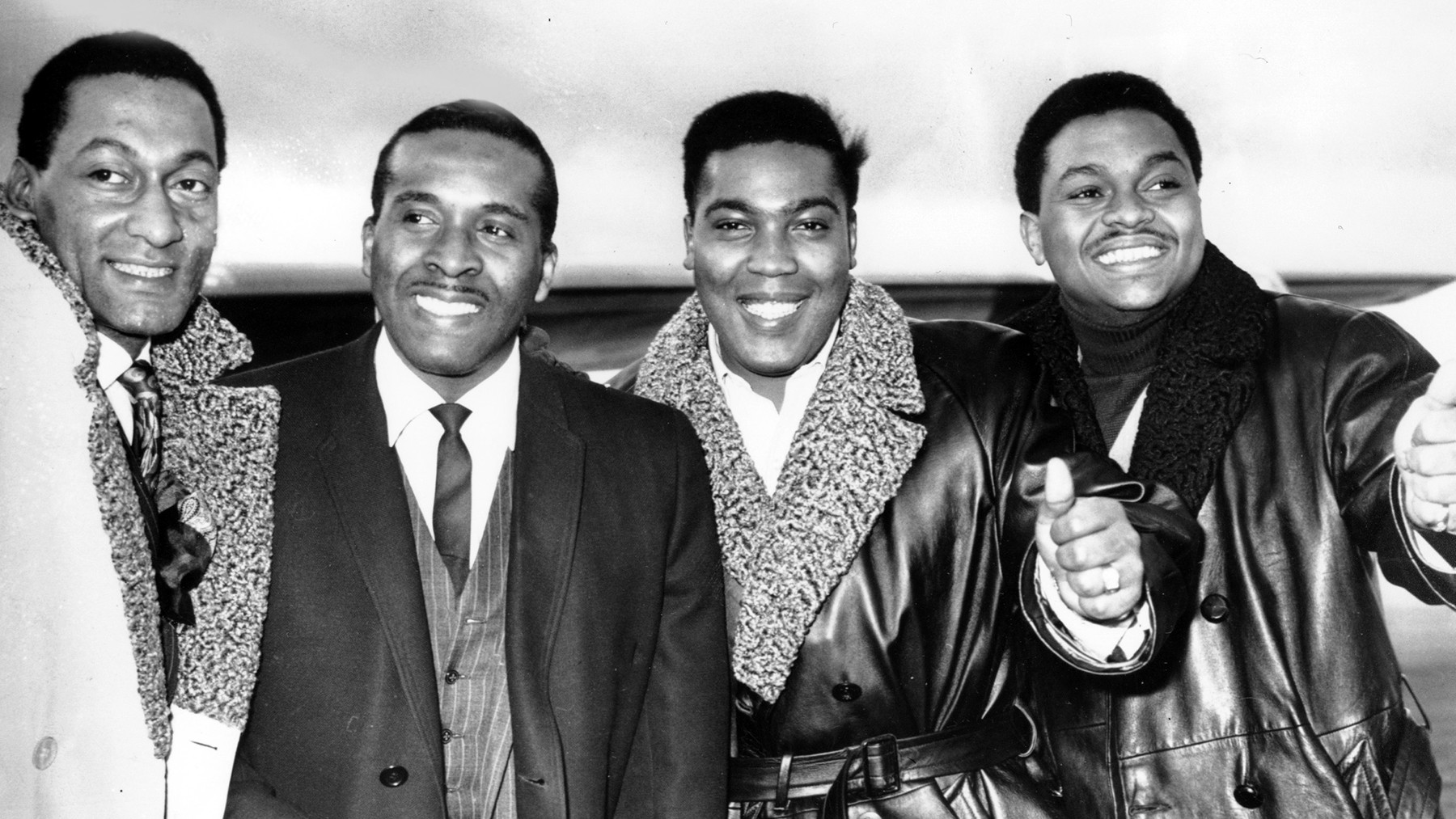

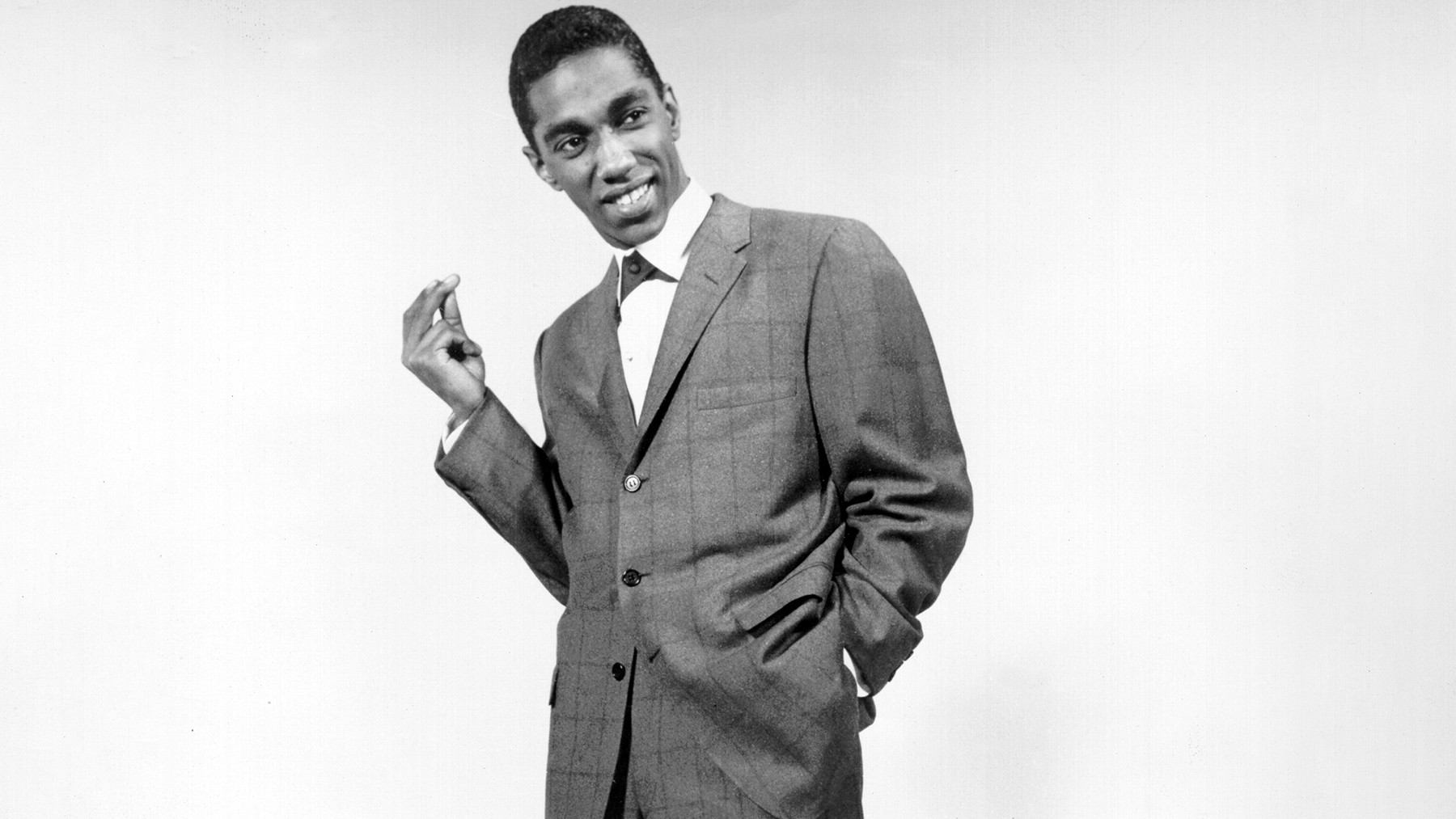

Barrett Strong, “Money (That’s What I Want)” (1959)

Barrett Strong in a 1960s portrait, known for singing Motown's first hit "Money (That's What I Want)".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Barrett Strong in a 1960s portrait, known for singing Motown's first hit "Money (That's What I Want)".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“Money (That’s What I Want)” is where it all began for Motown. Written by Berry Gordy and Janie Bradford in 1959, it became Motown’s first hit and a blueprint for the label’s future. The lyrics encapsulate Motown’s dual ambition for commercial and artistic success, while the distinctive piano bass line signifies R&B evolving into pop. Although “Money” was Barrett Strong’s only major hit as a performer, it marked the start of his significant career behind the scenes. After a brief stint as a singer with other labels, he returned to Motown to form a prolific songwriting partnership with Norman Whitfield, shaping much of the label’s iconic sound. —K.H.

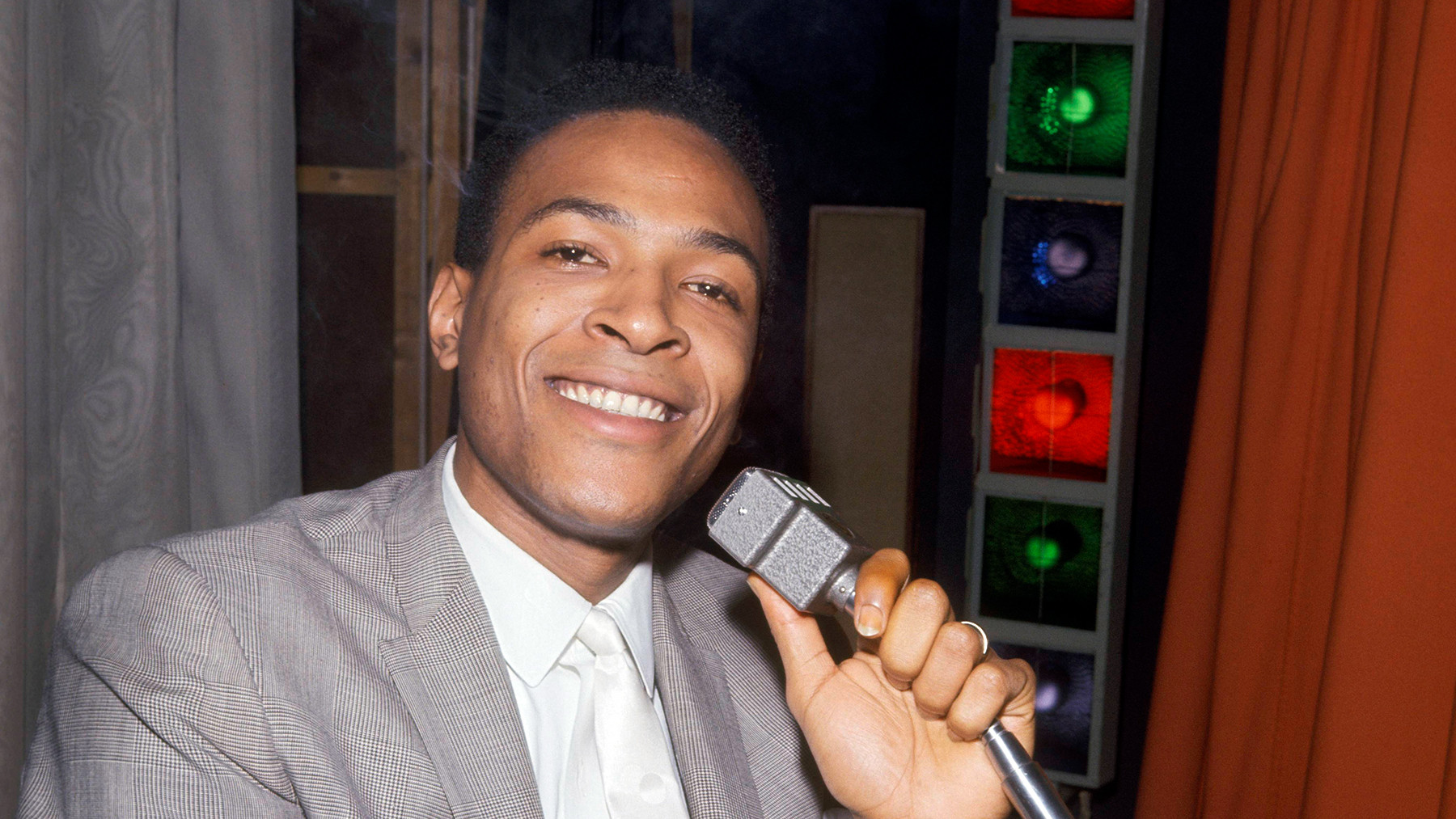

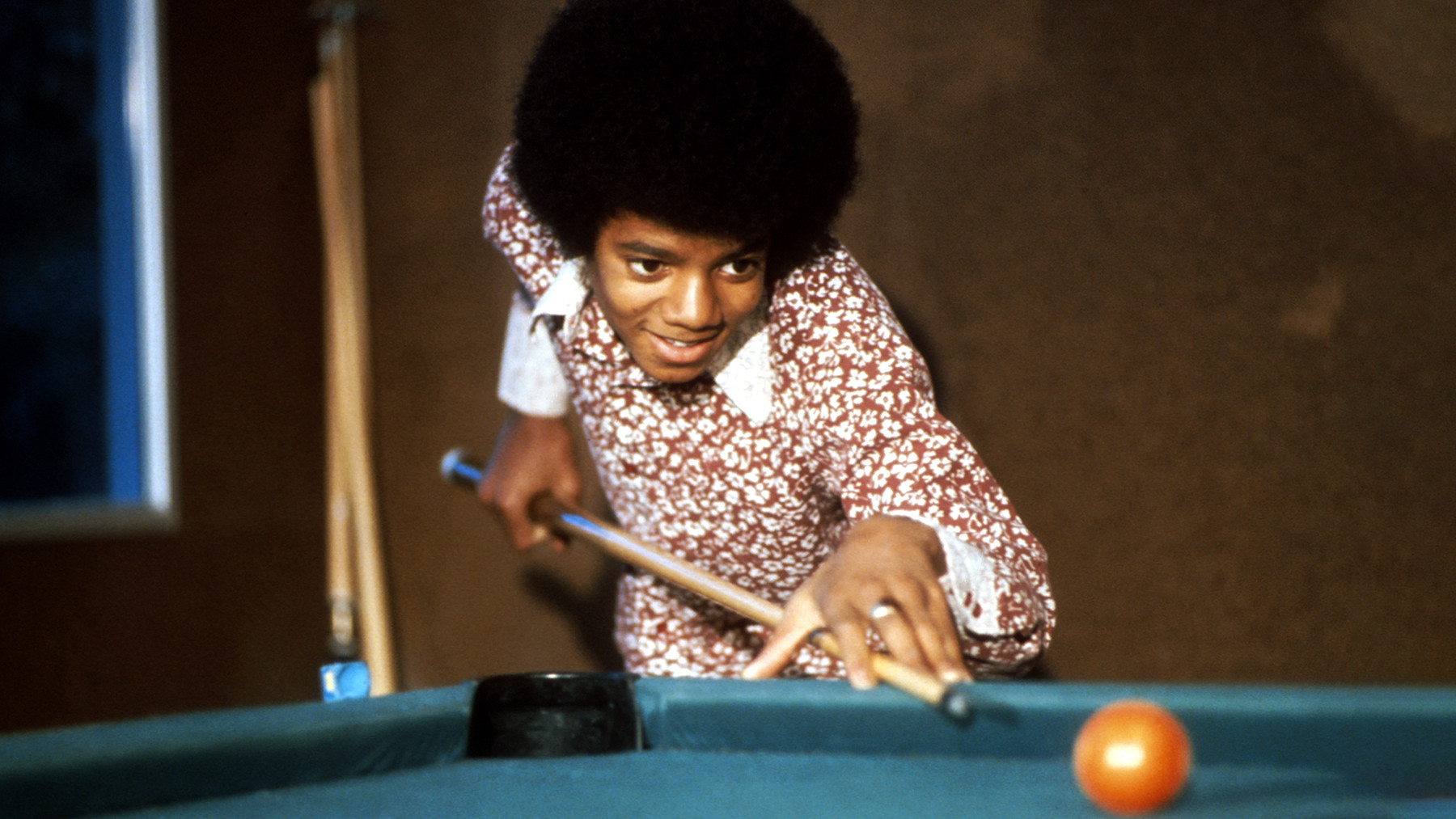

Michael Jackson, “Got to Be There” (1972)

Michael Jackson in a 1972 portrait, marking the start of his solo career with "Got to Be There".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Jackson in a 1972 portrait, marking the start of his solo career with "Got to Be There".Image Credit: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

“Got to be there in the morning/And welcome her into my world,” sang a 13-year-old Michael Jackson on his debut solo single. His brothers provided backing vocals, with a lush arrangement by Willie Hutch. Michael’s voice, still youthful and sweet, conveyed a depth of emotion that appealed to adult R&B audiences. This marked the beginning of Michael’s solo journey, showcased on an album where he also covered songs by Carole King and Bill Withers, signaling his artistic breadth and future trajectory beyond The Jackson 5. —J.D.