We all have those songs that get stuck in our heads, tunes that make us tap our feet and hum along without a second thought. But what happens when you actually listen to the words? You might be surprised to find a sinister story lurking beneath a catchy melody. This is especially true with murder ballads, and few exemplify this delightful dichotomy better than “Mack the Knife.”

Like the author of the original piece, I too have always been drawn to songs that sound cheerful on the surface but harbor darker narratives. It’s a cultural phenomenon, this tendency to absorb music passively, focusing on rhythm and melody while letting the lyrical content fade into the background. Think about how many times you’ve sung along to a song without truly considering what you were saying. It’s only when we consciously dissect the lyrics that we uncover the layers of meaning and intention woven into the music.

This exploration of lyrical depth leads us to a classic: “Mack the Knife.” Before we dive into the chilling narrative spun within the song’s verses, let’s explore the fascinating history of this deceptively upbeat tune.

Bobby

Bobby

From Opera Stage to Jazz Standard: The Ballad of Mack the Knife

Originally titled “Die Moritat von Mackie Messer,” “Mack the Knife” is a creation of the legendary duo Kurt Weill (composer) and Bertolt Brecht (lyricist). It was written for their groundbreaking music drama, Die Dreigroschenoper (The Threepenny Opera). This German opera, which premiered in Berlin in 1928, was itself an adaptation of John Gay’s 1728 The Beggar’s Opera. Gay’s work, in turn, drew inspiration from the real-life exploits of Jack Sheppard (1702-1724), a notorious thief, burglar, and escape artist of his time. From this lineage of rogues and rebels, the character of Macheath, the central figure of The Beggar’s Opera, was born and subsequently amplified in Die Dreigroschenoper.

“Die Moritat von Mackie Messer,” or “The Ballad of Mack the Knife,” quickly rose to prominence as the signature song of the opera. The term “Moritat” itself is significant; it refers to a type of German folk song that narrates gruesome tales, often of murder, typically performed by street singers. This origin sets the stage perfectly for the dark humor and underlying menace of “Mack the Knife.”

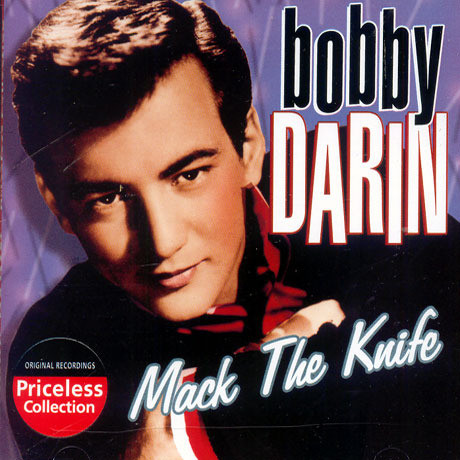

While the opera provides a rich context, the song gained even wider popularity through various interpretations, most notably Bobby Darin’s swinging 1959 rendition, which catapulted it into a jazz standard. Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald also delivered memorable versions, each adding their unique flair to the macabre melody. For our lyrical journey, we’ll primarily focus on the Bobby Darin version, but acknowledging the song’s diverse interpretations enriches our understanding of its enduring appeal.

Unpacking the Lyrics: Line by Line with Mack the Knife

“Oh, the shark, babe, has such teeth, dear”

The opening line immediately establishes a metaphor that runs throughout the song: Macheath is likened to a shark. The “teeth” are clearly his weapon of choice – a knife. The imagery is predatory and sets a tone of lurking danger.

“And it shows them pearly white”

“Pearly white” suggests a clean, sharp blade. It’s not about the material of the knife, but rather emphasizing its deadly efficiency. The German translation, “And the shark, it has teeth, And it wears them in its face,” highlights the directness and almost casual display of menace.

“Just a jackknife has old MacHeath, babe”

Here, we get the explicit mention of the weapon: a jackknife. The serrated edge hinted at earlier becomes clearer. “Old MacHeath” gives the character a familiar, almost folksy persona, despite his deadly profession. In Gay’s original opera, Macheath is a highwayman and thief, but the German adaptation elevates him to a murderer, adding a layer of chilling sophistication.

“And he keeps it, out of sight”

This line underscores Macheath’s cunning and stealth. He’s not a brute brandishing his weapon openly; he’s calculated and discreet, operating in the shadows.

“Ya know when that shark bites with his teeth, babe / Scarlet billows start to spread”

The shark metaphor returns, now with action. “Scarlet billows” is a poetic euphemism for blood, a vivid yet less graphic way to describe the aftermath of violence. The imagery is dramatic, evoking a sense of spreading crimson, further amplified by the alliteration.

“Fancy gloves, though, wears old MacHeath, babe / So there’s never, never a trace of red”

This is where Macheath’s calculated nature truly shines. The “fancy gloves” detail adds a touch of unexpected elegance to a murderer. It’s a practical measure to avoid leaving fingerprints or blood, highlighting his meticulous planning and almost nonchalant approach to crime. The OJ Simpson reference in the original article, though perhaps a bit dated, still resonates in illustrating the infamous association of gloves and criminal evasion.

“Now on the sidewalk, sunny mornin’, lies a body just oozin’ life”

The stark contrast between the cheerful “sunny mornin'” and the gruesome “body just oozin’ life” creates a jarring and unsettling image. “Oozing life” is a powerful and disturbing way to depict someone dying, emphasizing the slow, agonizing loss of life. The juxtaposition of peace and violence intensifies the shock value.

“And someone’s sneakin’ ’round the corner, could that someone be Mack the Knife?”

This is the pivotal moment where Macheath’s notoriety solidifies. “Mack the Knife” becomes his legendary moniker, a name whispered in fear and fascination. The question format adds a layer of plausible deniability, reflecting the opera’s narrative where Macheath, despite being obviously guilty, operates with impunity due to his connections and the corruption of the society around him. The original article correctly points out the parallel to media-given nicknames for serial killers, further cementing Macheath’s status as a figure of criminal legend.

“There’s a tugboat down by the river with a cement bag just droopin’ on down”

The imagery shifts to disposal. The “cement bag” is a classic trope of underworld crime, suggesting a body being weighted down to sink in the river. It’s a dark and pragmatic detail, hinting at the efficient and ruthless nature of Macheath’s operations.

“Oh, that cement is just, it’s there for the weight, dear”

This line, delivered with a casual “dear,” is chillingly matter-of-fact. It’s as if Macheath is explaining the practicalities of body disposal in the most nonchalant way possible, almost to an intimate confidante. The monstrous detail is delivered with unsettling calmness.

“Five’ll get ya ten old Macky’s back in town”

This line is famously ambiguous and subject to varied interpretations. The original article suggests “five bags will get you ten people,” or a prison sentence interpretation. Another reading could be a betting line, suggesting that it’s a sure bet (“five to ten odds”) that Mack is back to his old ways in town. The ambiguity adds to the song’s mystique and sinister undertones.

“Now d’ja hear ’bout Louie Miller? He disappeared, after drawin’ out all his hard-earned cash”

The narrative shifts to specific victims. Louie Miller’s story introduces a personal element to Macheath’s crimes. Drawing out “hard-earned cash” suggests robbery as a motive, adding another layer to Macheath’s criminal profile beyond just murder.

“And now MacHeath spends just like a sailor”

The influx of cash is circumstantial evidence pointing to Macheath’s involvement in Louie Miller’s disappearance. “Spending like a sailor” implies lavish and reckless spending, contrasting with a pauper’s typical behavior and drawing unwanted attention, as the original article notes.

“Could it be our boy’s done somethin’ rash?”

“Our boy” is dripping with irony. It’s a sarcastic, almost mocking way to refer to a notorious murderer. The question again maintains a facade of doubt, while the evidence mounts against Macheath. The shift in behavior – from discreet to conspicuous spending – signals a potential change in Macheath’s modus operandi, or perhaps an overconfidence in his impunity.

“Now Jenny Diver, Sukey Tawdry, Miss Lotte Lenya and old Lucy Brown”

This verse introduces a list of women’s names, famously including Lotte Lenya, Kurt Weill’s wife, added in Louis Armstrong’s version. In the opera, these women are associated with Macheath, often as lovers or wives. The original article mentions polygamy, which, while exaggerated, reflects Macheath’s exploitative relationships with women within the opera’s context. Polly Peachum, a central female character in the opera, was replaced by Lotte Lenya in some versions, highlighting the evolving nature of the song across different performances.

“Oh, the line forms on the right now that Macky’s back in town”

The final verse delivers a chilling punchline. “The line forms on the right” is interpreted as women lining up, perhaps drawn to Macheath’s dangerous allure, or unknowingly walking into danger. The “line to die” interpretation from the original article is a stark and powerful reading, suggesting these women are queuing up for their own demise at the hands of Mack the Knife. It solidifies the song’s dark humor and Macheath’s predatory nature.

The Enduring Appeal of Dark Humor in “Mack the Knife”

“Mack the Knife” is more than just a song; it’s a narrative masterpiece wrapped in a deceptively cheerful tune. Its enduring appeal lies in its masterful blend of dark humor, social commentary, and musical brilliance. The song originated as a critique of bourgeois society, masking its own criminality and corruption behind a veneer of respectability, a theme powerfully present in Die Dreigroschenoper.

The catchy melody, combined with the chillingly casual lyrics detailing murder and mayhem, creates a fascinating tension that captivates listeners. It’s a song that invites you to sing along, even as it recounts gruesome deeds. This unsettling juxtaposition is precisely what makes “Mack the Knife” so compelling and why it continues to fascinate audiences decades after its creation. From its operatic origins to its jazz standard status, “Mack the Knife” remains a testament to the power of music to explore the darkest corners of the human condition with a wink and a swing.