The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 was a global tragedy, capturing the world’s attention and embedding itself deeply into the collective memory. While the disaster predominantly affected the white upper and middle classes, its impact resonated surprisingly within African American folk and blues music. Initially skeptical, as perhaps any teenager might be when their father announces a slightly unconventional research topic, an exploration into this area reveals a rich and complex response to the Titanic tragedy within Black musical traditions. This article delves into the fascinating world of “Songs On Titanic,” examining why and how this maritime disaster became a subject in African American folk and blues repertoire, offering a unique perspective on the event and its cultural significance.

Contrary to initial assumptions, the Titanic disaster did indeed find its way into the blues and Black folk songbook. Compilations like “People Take Warning” (Tompkins Square, 2007), a 3-CD box set anthology of disaster songs from American folk traditions, including both white and Black artists, begins with a 1932 recording about the 1912 shipwreck. Further evidence emerges from a 1998 CD by the Teagarden label, dedicated exclusively to eighteen Titanic songs remastered from 78-rpm records. Beyond these compilations, a broader search reveals a range of blues artists who have recorded Titanic songs, from gospel singer Bessie Jones, who revisited the theme in 1961 and 1973, to Flora Molton’s 1980 rendition, and John Koerner’s 1992 “Titanic,” followed by Rory Block in 1998. Even German blues performer Abi Wallenstein recorded his “Titanic” in 2003. The sheer volume of these songs demonstrates that the blues genre was far from “deaf” to the Titanic phenomenon.

The pervasiveness of the Titanic story across various media, from cartoons and poems to films and advertisements, highlights its profound entry into Western collective memory. Phrases like “women and children first,” attributed to Captain Edward Smith, became ingrained in popular vocabulary. The centennial commemorations further solidified the event’s cultural significance, serving as a stark reminder against human hubris in the face of nature’s power. Given this widespread cultural saturation, it becomes less surprising that the blues tradition, a genre known for reflecting societal realities and emotions, would also engage with the Titanic narrative.

However, the question remains: why the blues? Several factors might initially suggest the Titanic disaster would not be a subject of interest within Black folk and blues. Firstly, the Titanic was a transatlantic event, far removed from the immediate, localized experiences often chronicled in folk music. The disaster’s prominence was largely driven by newspaper accounts and printed culture, potentially clashing with the oral traditions of folk music. More crucially, the African American community was not directly impacted by the Titanic tragedy. Historical records indicate only one Black passenger, Joseph Laroche, a Haitian man of French nationality, traveling with his white family. Events like the 1927 Mississippi flood or the 1940 Natchez dance hall fire, which directly affected Black communities, would seem more natural subjects for blues songs. Why then did the sinking of a ship carrying predominantly white passengers become a theme in Black vernacular song?

Furthermore, blues music is deeply rooted in personal and communal experience, serving as an outlet for emotions and commentary on the oppressive realities faced by African Americans. The Titanic disaster, primarily affecting white society, seemingly fell outside this sphere of direct experience. The daily hardships of racial segregation, economic disparity, and the pervasive “Jim Crow” laws were the immediate concerns of the Black populace in the early 20th century. Why would a tragedy befalling a “white-lily” vessel resonate with a community grappling with such profound and immediate injustices? Indeed, as observed, the Black press at the time gave minimal coverage to the Titanic, prioritizing the pressing issues of civil rights and the fight against lynching. From this perspective, the Titanic disaster might appear an unlikely candidate for inclusion in the blues repertoire.

Despite these compelling arguments against Black engagement with the Titanic story, the evidence clearly indicates otherwise. African American folk song and culture embraced the topic, integrating it into their musical narratives relatively quickly. Huddie Leadbetter, also known as Leadbelly, recalled performing a Titanic ballad, “Fare Thee Well, Titanic,” with Blind Lemon Jefferson around 1912, suggesting the song’s almost immediate emergence within the Black musical landscape. Leadbelly later stated “The Titanic” was the first song he learned on a 12-string guitar, further emphasizing its early adoption.

In 1913, Butler “String Beans” May, a vaudeville star, even claimed to have been a survivor of the Titanic, attributing his survival to his athleticism. String Beans, a pioneering Black entertainer who achieved success outside mainstream white approval, incorporated the Titanic theme into his piano piece “Titanic Blues,” showcasing the event’s integration into Black performance culture. Eyewitness accounts describe his energetic performances, vividly portraying the ship’s sinking through music and movement.

Reports from the 1910s, predating commercial blues recordings, document the collection of Titanic-related folk songs across the American South, indicating a widespread and early interest in the subject within Black communities. By 1920, “When That Great Ship Went Down” was being sung by Black musicians in North Carolina. Folklorist Newman Ivey White noted in 1928 how these early songs demonstrated improvisation and the adaptation of older verses to create new songs relevant to contemporary events like the Titanic sinking.

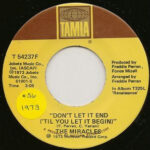

The Titanic’s presence in Black music persisted even with the rise of commercial blues recordings. While the exact motivations – whether driven by artists, record companies, or folk song collectors – remain nuanced, numerous recordings attest to the theme’s continued appeal. Ma Rainey, the “Mother of the Blues,” recorded “Titanic Man Blues” in 1925, followed by Virginia Liston’s “Titanic Blues” a few months later. Richard “Rabbit” Brown, a significant blues artist from the pre-acoustic blues era, recorded “Sinking of the Titanic” in 1927, offering a detailed narrative of the shipwreck, likely informed by his own experiences as a ferryman. His lyrics paint a vivid picture:

It was on the 10th of April on a sunny afternoon

The Titanic left Southampton, each one as happy as a bride and groom

No one thought of danger or what their fate may be

Until a gruesome iceberg caused 1500 to perish in the sea

It was early Monday morning, just about the break of day

Captain said call for help from the Carpathia and it was many miles away

Everyone was calm and silent, asked each other what the trouble may be

Not thinking that death was lurking there upon that northern sea

The Carpathia received the wireless SOS re distress

Come at once, we are sinking, make no delay and do your best

Get the lifeboats all in readiness ‘cos we’re going down very fast

We have saved the women and the children and tried to hold out to the last

Blind Willie Johnson’s seminal 1929 blues song, “God Moves on the Water,” also references the “Great Titanic” striking an iceberg, further cementing the event’s place in the blues canon. Mance Lipscomb, who learned the song from Johnson, continued to perform it, ensuring its legacy. Non-commercial recordings for the Library of Congress, such as Huddie Ledbetter’s 1935 “The Titanic,” and later recordings by artists like Hi” Henry Brown in 1932 (“Titanic Blues”), Pink Anderson in the 1950s, and Mance Lipscomb in the 1960s, demonstrate the enduring presence of the Titanic theme across decades of Black folk and blues music.

Interestingly, Leadbelly’s “Hindenburg disaster” song reveals that Black disaster songs weren’t solely limited to events directly impacting the Black community. Similarly, Sam Hopkin’s songs about hurricanes, like “That Mean Old Twister” and “Hurricane Betsy,” suggest a broader interest in large-scale disasters, possibly fueled by personal anxieties, in Hopkin’s case, a fear of flying.

However, the majority of Black disaster songs did focus on calamities with direct or indirect consequences for Black communities. The Great Mississippi River Flood of 1927, for instance, spawned numerous songs like Charley Patton’s “High Water Everywhere.” The devastating drought of the 1930s, coinciding with the Great Depression, was reflected in songs like Son House’s “Dry Spell Blues.” The “Dust Bowl,” an environmental catastrophe that severely impacted Black agricultural communities, also found its place in song. The tragic Natchez Dance Hall fire of 1940, claiming over 200 Black lives, resonated in songs like Howlin’ Wolf’s “The Natchez Burnin’.” Considering this pattern, the question becomes even more pointed: why the Titanic? Why did this disaster, seemingly disconnected from the Black experience, inspire such a significant body of Black songs?

The key to understanding the prevalence of “songs on Titanic” lies not merely in the scale of the tragedy itself, but in the way the mainstream Anglo-Saxon culture presented and interpreted the disaster. The Black vernacular response was less a direct reaction to the sinking and more a “signifying” response to the dominant cultural narrative surrounding it. As Steven Biel argues, the Titanic disaster became a “social drama” in Progressive Era America, a moment where societal tensions and conflicts were played out, and American culture “thought out loud about itself.” To understand the Black musical response, we must examine the key elements of this mainstream interpretation.

The initial news coverage of the Titanic disaster in April 1912, reveals a mixture of uncertainty and disbelief. Early reports even suggested the ship was still afloat and heading to New York. Simultaneously, materialistic concerns surfaced, with newspapers speculating about insurance payouts and the value of passenger’s jewelry and bonds aboard the ship, even on the same front pages announcing the staggering death toll.

As details emerged, the mainstream narrative solidified, shaped by official pronouncements, press coverage, sermons, and popular songs. The Titanic was initially framed as a symbol of British imperial power and technological prowess. Its very name, “TITANIC,” evoked might and invincibility. However, beneath the surface of British symbolism lay the reality of American financial control, with J.P. Morgan’s ownership of the White Star Line. The Titanic, therefore, represented a transatlantic white hegemony, an emblem of Anglo-Saxon achievement, not universal humanism. It was presented, first and foremost, as a testament to white, Anglo-Saxon heroism.

The dominant white public discourse surrounding the Titanic centered on themes of guilt and heroism. Official inquiries, like the US Senate investigation, sought to assign responsibility, though ultimately avoided naming specific culprits. Nevertheless, the concept of “reprehensible conduct” was invoked. Transatlantic solidarity frayed as blame was apportioned. J. Bruce Ismay, the British chairman of the White Star Line who survived, was vilified by the American press and public, deemed a “coward” for prioritizing luxury over safety and surviving while others perished. In contrast, wealthy American passengers like J.J. Astor, who died, were lionized as heroes. The narrative became populated by heroes and cowards, reinforcing Christian ideals of self-sacrifice, where men, particularly wealthy first-class men, heroically gave their lives to save women and children.

This mainstream white response conveniently overlooked gender, class, and race relations, focusing instead on universal values of heroism and sacrifice. The “women and children first” protocol, while not a universal maritime law, was elevated as a symbol of chivalry and Victorian-era gender ideology. It reinforced existing gender hierarchies, celebrating male bravery in protecting “weaker” women and children. This focus on gender and age obscured the underlying class and race dynamics. The “women and children” doctrine served to bridge class and race divides, framing the disaster narrative through the lens of gendered strength and weakness. The dominant white response, therefore, became a conservative narrative, reinforcing existing power structures between genders and classes, while completely ignoring the racial dimension.

The Titanic story, as told by the white mainstream, became a morality tale of heroism and sacrifice, implicitly upholding existing social hierarchies and inequalities. It became woven into the fabric of American culture, a culture that simultaneously denied Black Americans equal rights. The Black folk and blues engagement with the Titanic must be understood as a response to this white narrative, rather than solely to the factual disaster itself. The Titanic event became another point of commentary for African Americans on a system that systematically oppressed them. The Black vernacular Titanic story is a form of “signifying,” a reinterpretation and re-articulation of the dominant narrative through a Black cultural lens.

African Americans “signified” on the white Titanic story, reshaping its plot, characters, and tone to express their own experiences and perspectives. Humor and irony, key elements of Black consciousness, permeated these musical reinterpretations, sometimes even turning the tragedy into a source of dark humor. This “rewriting” touched upon core themes of the white narrative: gender, spirituality, class, and especially race.

Ma Rainey’s “Titanic Man Blues” (1928), though not explicitly detailing the disaster, utilizes the Titanic metaphor to critique gender relations. Rainey uses “Titanic” to describe an unfaithful, arrogant lover, whose “unsinkable” self-image, fueled by “high-priced wine,” ultimately leads to the “sinking” of their relationship. This subverts the chivalrous male figure of the mainstream narrative, presenting a self-assured woman who dismisses a flawed man, challenging conventional gender roles.

The spiritual dimension of the white Titanic narrative emphasized Christian sacrifice, aligning the male passengers’ selflessness with the teachings of Jesus. The dominant interpretation focused on the “God of the New Testament,” a God of redemption and mercy. In contrast, the Black narrative emphasized divine judgment, drawing upon the “God of the Old Testament,” a God of wrath and justice. The Titanic’s sinking was interpreted as “divine punishment” for the hubris of claiming the ship was unsinkable, a challenge to God’s power. This resonated with the historical emphasis on the Old Testament in African American spirituality, where figures like Moses, leading his people out of oppression, resonated deeply. The Black Titanic songs presented a vengeful God, reminding humanity of its limitations and the ultimate power of the divine.

J. Laroche and family

While less prominent than gender and spirituality, the class dimension also received attention in Black Titanic songs. Mance Lipscomb’s version of “God moves on the water” includes a verse highlighting the futility of wealth in the face of death:

“Jacob Astor was a millionaire,

Had plenty money to spare;

But when the Titanic was sinking,

Lord, he could not pay his fare.”

Pink Anderson’s “The Ship Titanic” (1950) directly addresses class segregation on the ship, noting, “the rich had declared they wouldn’t ride with the poor. So they put the poor below.” William and Versey Smith’s 1927 recording also touched upon this theme. These verses subtly critique the class divisions inherent in the Titanic tragedy, highlighting the shared vulnerability of all in the face of disaster, regardless of social standing.

However, it was the race aspect, or rather the absence of race in the white narrative, that spurred the most significant and transformative “signifying” in Black Titanic songs. This reinterpretation involved a complete tonal shift and the introduction of new characters, fundamentally altering the meaning of the Titanic story. The historical reality of Joseph Laroche, the Black Haitian passenger, was largely ignored in mainstream Titanic narratives until recently, reinforcing the perception of the Titanic as a white tragedy. Both white and early Black interpretations operated under the assumption of a racially homogenous passenger list.

While not devoid of empathy for the loss of life, the Black response often incorporated a sense of ironic detachment and even celebration at the absence of Black casualties. Leadbelly’s lyrics encapsulate this sentiment:

“Black man oughta shout for joy,

Never lost a girl or either a boy.

Cryin’, “Fare thee Titanic, fare thee well!”

This celebratory tone is amplified by the recurring rumor in Black Titanic lore that Jack Johnson, the first African American heavyweight boxing champion, was denied passage on the Titanic due to his race. This hypothetical refusal, while likely apocryphal, resonated with the racial realities of the time. Johnson’s victory over white boxer James J. Jeffries in 1910, “The Fight of the Century,” had shattered white supremacist ideals, leading to racial riots and Black celebrations. The myth of Johnson’s Titanic rejection became a symbolic reaffirmation of Black triumph over white prejudice. Leadbelly’s song depicts Johnson reacting to the Titanic’s sinking with joyful dance, “doin’ th’ eagle rock,” far removed from the tragedy, safe and celebratory on land.

The boxing motif reappears in Bill Gaither’s 1938 “Champ Joe Louis,” connecting the Titanic to Joe Louis’s victory over German boxer Max Schmeling. Gaither’s song equates Schmeling’s defeat to the Titanic’s sinking, linking both to the downfall of perceived “invincibility.” Schmeling’s earlier victory had been used by Nazi propaganda to promote white racial superiority. Louis’s 1938 rematch victory, therefore, carried immense symbolic weight, seen as a blow against Nazi ideology and white supremacy. By comparing Schmeling’s defeat to the Titanic’s sinking, Gaither further reinterprets the disaster as a moment of Black triumph over white arrogance and oppression.

While some Black Titanic songs shifted the tone of the narrative, others introduced a new character: Shine. String Beans’ early performance already hinted at this, with his boastful claim of Titanic survival. The “Shine and the Titanic” toasts, a popular form of Black oral narrative, fully developed this figure. Shine is typically depicted as a Black stoker or boiler room worker, a low-status crew member who becomes the central hero. He embodies the trickster figure in African and African American folklore, using wit and strength to subvert white authority, represented by the ship’s captain.

In the Shine toasts, Shine warns the captain of impending danger, but is ignored and ordered back to work. Shine, rejecting this order, jumps overboard and swims to safety, outswimming sharks and encountering various characters, including the captain’s daughter and the captain himself, who offer him rewards (money, sex, marriage) for rescue. Shine, however, rejects these offers, prioritizing his own survival and recognizing the superficiality of white promises. He reaches shore while the Titanic sinks, leaving the white passengers to their fate.

The Shine toasts are rich in “signifying.” They invert the racial power dynamic, demonstrating that white dominance is not absolute, especially when survival is at stake. Race and wealth become irrelevant in the face of disaster. Shine’s triumph challenges racism, economic inequality, and white privilege. The figure of Jim, in some versions, who accepts the white woman’s offer and perishes, serves as a cautionary tale against succumbing to white enticements and betraying Black self-interest.

The Shine narrative can also be interpreted through the lens of the transatlantic slave trade, the “Middle Passage.” Shine’s successful swim to shore can be seen as a reversal of the forced and deadly Middle Passage. He becomes the negotiator, controlling his own fate and rejecting the exploitative bargains offered by white authority. The white captain, in contrast, “drowns” in this symbolic exchange. Shine’s mobility, his ability to choose his own path to safety, contrasts with the illusory mobility of the white passengers, whose wealth and privilege ultimately failed them. The Shine toast, in this interpretation, connects to the broader theme of travel and mobility in blues and Black folk song, emphasizing Black agency and self-determination.

While the Black community developed its unique Titanic “myth,” other groups also offered alternative interpretations. Left-wing groups saw the Titanic as a symbol of capitalist failure. Feminists critiqued the “women and children first” doctrine, questioning whether it truly represented chivalry or rather a patriarchal view of women as weak and in need of male protection, and highlighting the potential for male self-preservation masked as heroism.

However, the Black response stands apart as a profound act of “signifying,” a rewriting of the dominant narrative rather than mere reinterpretation. It shifted the tone from mourning to ironic celebration, introduced the transformative figure of Shine, and directly confronted issues of race, class, and power. Through Shine, Black folk lore crafted its own “Titanic blockbuster,” a powerful commentary on Black reality, resilience, and resistance in the face of a white-dominated society. In closing, the lyrics from a Shine toast poignantly summarize this perspective:

“Big man from Wall Street came on second deck.

In his hand he held a book of checks.

He said, “Shine, Shine, if you save poor me,

“Say I’ll make you as rich as any black man can be.”

Shine said: “You don’t like my color and you down on my race,

Get your ass overboard and give these sharks a chase”

Notes

(1) “Elgin Movements” refers to the Elgin National Watch Company, a major American watch manufacturer whose products were synonymous with quality and represented a shift towards industrialization and affordability. The term became blues slang for a woman’s elegant and curvaceous movements, comparing her body to the intricate workings of a fine watch.

(2) The tradition of boasting about being absent from disaster scenes is indeed present in Black folk songs, highlighting a sense of survival and resilience in the face of tragedy.

(3) “Hey Shine,” recorded by Delmar Evans as “Snatch and the Poontangs,” exemplifies the explicit and often subversive nature of some Shine toasts, foreshadowing later developments in rap music.

(4) The anecdote about feminist passengers on the Titanic is presented ironically in the original text, questioning the simplistic “chivalry” narrative.

Further Reading

– Chris Smith, The Titanic, a case Study of Religious and Secular Attitudes in African American Song, in: Robert Sacré (ed.), Saints and Sinners, 1996

– Steven Biel, Down with the Old Canoe: a cultural history of the Titanic Disaster, 1997

– Mike Ballantyne, The Titanic and the Blues (EarlyBlues.com)

– Bruce Jackson, Get Your Ass in the Water and Swim like me, 1975/2004

– Steven Biel, Unknown and Unsung: Contested Meanings of the Titanic Disaster, in: Danky & Wiegand: Print Culture in a diverse America, 1998

– Alan Rice, Radical Narratives of the Black Atlantic, 2003

– Leon Dixon, “Shine”, A Folk Narrative, 1992

– Lucy Delap, Thus does man prove his fitness to be the master of things: Shipwrecks and Chivalry in Edwardian Britain (corpus.cam.ac.uk)

– Seth Borenstein, Titanic’s legacy: A fascination with disasters, 2012 (new.yahoo.com)

– Edward Komara, Encyclopedia of the Blues, 2005