A vintage jukebox displaying the words "A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs" and the website logo.

A vintage jukebox displaying the words "A History of Rock Music in 500 Songs" and the website logo.

The period spanning from February 1967 to December 1968 was transformative for The Rolling Stones. While encompassing just under two years, this era witnessed the band grapple with creative shifts, legal battles, and personal turmoil, ultimately forging the sound and image that would define them as rock icons. This crucial period, marked by experimentation and a return to their blues roots, is essential for understanding the evolution of their iconic discography, and the enduring legacy of Songs By The Rolling Stones.

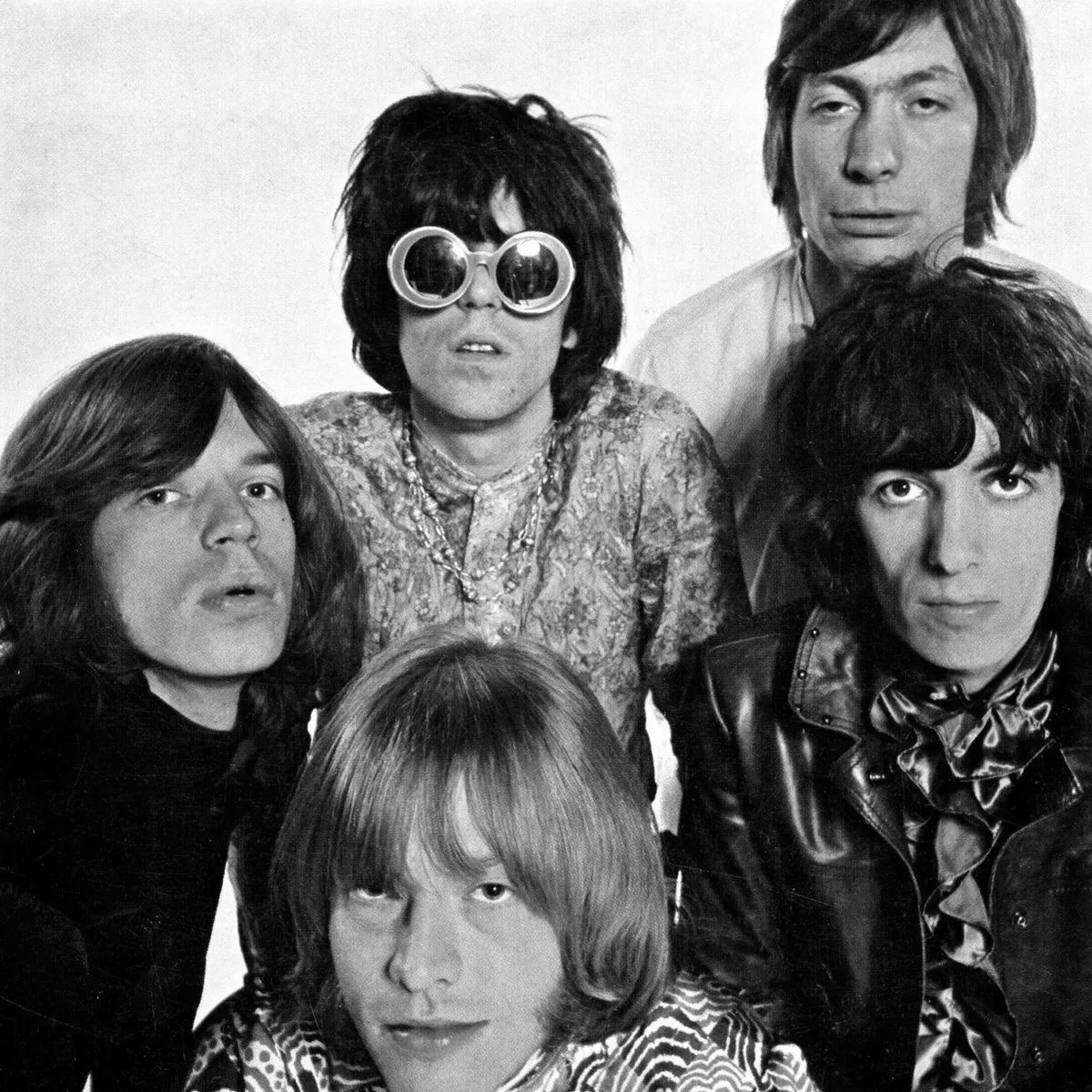

The Rolling Stones lineup in 1968, featuring Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts.

The Rolling Stones lineup in 1968, featuring Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts.

The Psychedelic Detour and “Their Satanic Majesties Request”

Inspired by the Beatles’ groundbreaking Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones, Bill Wyman, and Charlie Watts ventured into psychedelic experimentation. This phase culminated in their 1967 album, Their Satanic Majesties Request. This album, while often compared unfavorably to Sgt. Pepper’s, represents a significant, if debated, chapter in songs by The Rolling Stones.

Tracks like “She’s a Rainbow” showcased Brian Jones’s mellotron skills and a more ornate, layered sound, diverging from their R&B origins. The song, with its “She comes in colors” hook, echoing Love’s earlier track, hinted at the cross-pollination of musical ideas within the vibrant 60s music scene. However, the album as a whole was criticized for lacking focus and sounding derivative, a patchwork of ideas rather than a cohesive statement.

Critics and even band members themselves later expressed reservations about Their Satanic Majesties Request. Keith Richards described it as a “patchwork,” and Mick Jagger acknowledged only a few standout tracks. Ian Stewart bluntly called it “awful.” Despite its mixed reception, the album remains a fascinating artifact, illustrating the band’s willingness to explore new sonic territories, even if the result strayed from the core identity of songs by The Rolling Stones.

Legal Battles and Shifting Dynamics

The year 1967 also saw the Rolling Stones entangled in drug charges. A police raid at Keith Richards’ country home led to the arrests of Jagger, Richards, and art dealer Robert Fraser. This legal ordeal became a defining moment, sparking public debate about drug use and the treatment of counter-culture figures.

Mick Jagger’s famous quote, “We are not criminals, we are pop stars,” encapsulated the band’s defiant stance amidst the controversy. The Times newspaper, in a leader titled “Who Breaks a Butterfly On a Wheel?”, questioned the severity of Jagger’s sentence, further fueling public sympathy and shifting the narrative in their favor.

These legal challenges occurred alongside internal band tensions. Brian Jones, struggling with personal issues and substance abuse, became increasingly marginalized within the group. His creative contributions diminished, and his relationship with Richards and Pallenberg fractured after Pallenberg began a relationship with Richards during a trip to Morocco. This period marked a turning point for the band’s internal dynamics, setting the stage for significant changes in the years to come, and impacting the creation of songs by The Rolling Stones.

The Return to Roots and “Beggars Banquet”

By 1968, The Rolling Stones sought a course correction. Led by Keith Richards’s renewed interest in blues and a desire to move away from the perceived excesses of Their Satanic Majesties Request, the band began to gravitate back towards their raw, blues-rock foundation. This shift in direction was significantly influenced by artists like Blind Blake and Robert Johnson, whose music Richards immersed himself in during their time off the road.

This return to basics was further solidified by the arrival of producer Jimmy Miller. Miller, known for his work with Traffic and the Spencer Davis Group, brought a raw, energetic approach to the studio, contrasting sharply with the self-indulgent atmosphere that had characterized the Satanic Majesties sessions.

The result of this renewed focus was Beggars Banquet, released in December 1968. This album is widely considered a landmark in the discography of songs by The Rolling Stones, marking a triumphant return to form and setting the stage for their iconic 1970s output.

“Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” released as a single prior to the album, signaled this change. With its raw, distorted guitar riff and driving rhythm, the song was a powerful statement of intent. Richards famously achieved the song’s distinctive guitar sound by recording an acoustic guitar through a cheap cassette player, highlighting the band’s embrace of lo-fi techniques and raw energy.

“Street Fighting Man,” another key track from Beggars Banquet, reflected the turbulent political climate of 1968. Inspired by the Grosvenor Square anti-Vietnam War demonstration, the song captured the spirit of unrest and social change. Its acoustic-driven sound, again utilizing Richards’s tape-recorder distortion technique, further emphasized the album’s stripped-down aesthetic, contrasting with the orchestral arrangements of their previous work.

“Sympathy for the Devil”: A Song of Its Time

Perhaps the most iconic song to emerge from this period, and a cornerstone of songs by The Rolling Stones, is “Sympathy for the Devil.” Inspired by Mikhail Bulgakov’s novel The Master and Margarita, the song is a sprawling, multi-layered track exploring themes of good and evil, and the devil’s presence throughout history.

Filmed by Jean-Luc Godard during its recording for his film 1+1 (later released as Sympathy for the Devil), the song’s evolution in the studio is well-documented. Starting as a Dylanesque acoustic number, it transformed into a percussive, rhythmic tour-de-force, driven by Charlie Watts’s jazz-influenced drumming and Rocky Dijon’s conga rhythms.

The song’s rhythmic complexity, often mistakenly labeled as samba, drew inspiration from jazz drummers like Kenny Clarke and his work with Dizzy Gillespie. This rhythmic foundation, combined with Jagger’s evocative lyrics and the song’s hypnotic groove, made “Sympathy for the Devil” a powerful and enduring statement, perfectly capturing the zeitgeist of 1968.

Brian Jones’s Fading Role

Despite the creative resurgence of Beggars Banquet, Brian Jones’s contributions were minimal. His personal struggles and increasing detachment from the band are evident throughout this period. While he contributed slide guitar to “No Expectations” and mellotron to other tracks on Beggars Banquet, his involvement was sporadic and often hampered by his declining health and substance abuse.

The Rock and Roll Circus film, shot in December 1968, offered a poignant and ultimately tragic glimpse of Jones’s state. Visibly detached and struggling, his performance was a shadow of his former self, highlighting the band’s difficult decision regarding his future, a decision that would become unavoidable in the following year.

Conclusion

The years 1967 and 1968 were pivotal for The Rolling Stones. From the psychedelic explorations of Their Satanic Majesties Request to the blues-infused revolution of Beggars Banquet, this period showcased the band’s resilience and adaptability. Songs by The Rolling Stones from this era reflect a band navigating creative crossroads, legal pressures, and internal shifts, ultimately emerging stronger and more focused, ready to solidify their place as one of the greatest rock bands of all time. “Sympathy for the Devil” and Beggars Banquet stand as testaments to this transformative period, marking a crucial chapter in the ongoing story of songs by The Rolling Stones.