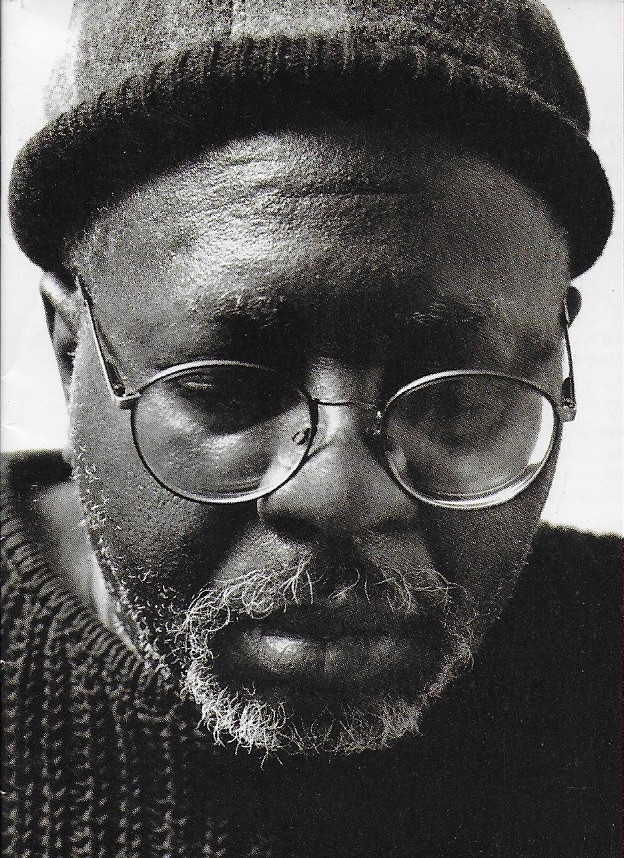

Curtis Mayfield performing

Curtis Mayfield performing

Thirty years ago, a tragic accident on September 13, 1990, at a Brooklyn open-air concert, changed Curtis Mayfield’s life forever, leaving him paralyzed from the neck down. Just three years later, a poignant interview took place at his Atlanta, Georgia home, offering a glimpse into the soul of a musical legend. This reflection explores Curtis Mayfield’s journey, his indelible songs, and the enduring impact of his music.

“There’s not really much to talk about,” Mayfield stated with a quiet acceptance, recalling the fateful day. “It happened, and it happened fast. I never even saw it coming.” He then recounted the ordinary beginnings of that late summer day in 1990. Arriving in New York from California, he traveled to New Jersey, preparing for a performance in Queens. The event was larger than anticipated, with around 10,000 people gathered in the park. After the usual pre-show routines, an adjustment to the schedule placed him on stage earlier than planned. He remembers tuning his guitar, changing into his stage attire, and the promoter’s son signaling his readiness. His band launched into “Superfly,” a track that epitomized the socially conscious narratives often found in Curtis Mayfield Songs.

Walking onto the stage, ascending ladder steps, his world turned upside down. “I get to the top of the back of the stage, I take two or three steps, and… I don’t remember anything. I don’t even remember falling.” The next moments were a stark awakening on his back, a terrifying realization of paralysis. Rain began to fall as chaos erupted around him. Amidst the screams, he lay helpless, choosing to keep his eyes open, clinging to life. Quick-thinking crew members shielded him from the rain until paramedics arrived, rushing him to a nearby hospital. “Everything else is history,” he concluded, his voice trailing off, the weight of the past palpable.

Silence filled the room as Mayfield lay in his bed, his gaze fixed beyond the white sheet. The tape recorder captured the stillness, mirroring the physical stillness that had defined his existence since that devastating night. His performing career, spanning three decades and filled with iconic Curtis Mayfield songs, was abruptly halted. A lighting rig malfunction had silenced one of America’s most significant poetic voices.

From Chicago’s Cabrini-Green to Soulful Songwriting

Born in 1942, Curtis Mayfield’s upbringing in Chicago’s Cabrini-Green housing projects profoundly shaped his artistic vision. Raised by his mother after his father’s departure, he found a guiding light in his grandmother, Reverend Annie Bell Mayfield. Her storefront church, the Traveling Soul Spiritualist Church, became a foundational influence. “She was the Reverend Annie Bell Mayfield, and she had a little storefront church,” he reminisced, highlighting the early exposure to spiritual rhetoric and powerful oration that would later echo in Curtis Mayfield songs. While no recordings of his grandmother’s sermons exist, one can easily discern her influence in his lyrical style and even his conversational grace, a blend of ghetto vernacular and King James Bible formality.

The church also served as his early musical training ground. He sang in the choir, absorbing various gospel music styles, developing a deep appreciation for groups like the Sensational Nightingales and the Original Five Blind Boys of Alabama. At home, amidst the constant hum of the Victrola and radio, he immersed himself in the sounds of Billie Holiday and doo-wop groups like the Spaniels and Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers. These diverse musical encounters laid the groundwork for the unique sound that would define Curtis Mayfield’s music.

His musical journey progressed from singing gospel with Jerry Butler in the Northern Jubilees to exploring instruments. Around age eight or nine, he started experimenting with a guitar, developing an unorthodox F-sharp open tuning. Despite its incompatibility with standard orchestral tuning, this unique approach became part of his signature sound. By his early teens, he was writing songs for his doo-wop quartets, using the acoustics of housing project stairwells as his studio. “Everything was a song,” he explained, emphasizing the innate songwriting impulse that transformed observations and emotions into music. His mother’s encouragement to read widely, introducing him to poet Paul Laurence Dunbar, further enriched his lyrical depth. Despite leaving high school early, he considered his real teachers to be the people around him, emphasizing the power of observation and listening, especially to the stories of elders.

Social Commentary Woven into Curtis Mayfield Songs

Curtis Mayfield’s keen awareness of social issues permeated his songwriting. Growing up as a young Black kid in the 1950s, he witnessed firsthand the injustices of racial inequality. He recalled the horrific Emmett Till case, a pivotal moment that underscored the brutal realities of racism. “All of these things come into your head. And of course the popularity of the Reverend Martin Luther King instilled in me the need to join in, to speak in terms of we as a minority finding ways to be a bit more equal in this country.” This burgeoning social consciousness became a defining characteristic of Curtis Mayfield songs.

Initially, the music industry resisted his socially charged lyrics. Songs like “We’re a Winner,” “Choice of Colors,” and “Mighty Mighty (Spade and Whitey)” with the Impressions challenged the status quo. “No, no. But I didn’t care. I couldn’t help myself for it,” he asserted, driven by his moral compass and a desire to address societal issues through his music. His introspective songwriting process often drew from his spiritual upbringing, using righteous self-talk to shape his narratives.

Reflecting on “People Get Ready,” perhaps one of the most iconic Curtis Mayfield songs, he struggled to pinpoint its exact origin, suggesting it emerged from a collective consciousness. He acknowledged the biblical influences in its lyrics, emphasizing its message of hope and judgment. “It’s an ideal. There’s a message there.” This song, like many Curtis Mayfield songs, transcended mere entertainment, becoming anthems of hope and social change.

Early in his career, Mayfield recognized the importance of owning his publishing rights. Driven by his family’s experience with poverty, he sought control over his creative output. At seventeen, he formed his own publishing company, a move that was unconventional in an industry often exploitative of artists. “I also understood early on that it’s better to have fifty per cent of something than a hundred per cent of nothing. And at least I had it to bargain with.” While acknowledging the challenges of the business side, his early understanding of publishing was remarkably prescient.

Curtis Mayfield’s journey with record labels included Vee Jay and ABC, where The Impressions delivered numerous hits. Inspired by Berry Gordy’s Motown success, he co-founded Curtom Records. However, Curtom, while significant, remained primarily a platform for his own work, unlike the expansive Motown empire. “We were all trying to survive in a big world of business and loopholes and record companies that weren’t giving you all you felt you’d earned,” he explained, admiring Gordy’s model but acknowledging the systemic barriers faced by Black artists. He felt that racial prejudice hindered his label’s growth, stating, “As a black man, you don’t get an invitation.”

Superfly and the Weight of Social Messages in Music

In 1972, at his creative peak, Curtis Mayfield composed the soundtrack for Superfly. This blaxploitation film provided a platform for him to address the escalating drug culture in communities like Cabrini-Green. Songs like “Freddie’s Dead” and “Pusherman,” while hugely popular, carried stark warnings about drug abuse, mirroring similar messages in James Brown’s “King Heroin” and Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On. Despite their popularity, he questioned if these warnings were truly heeded. “In some ways. Not really, because although sometimes all the bad things seem to be in a majority, it’s still really a small minority. The majority still has high hopes and reasons, and wants to do the right things and be about success stories.” He maintained a hopeful perspective, believing in the underlying goodness and aspirations of the majority, even amidst societal challenges.

Reflecting on the changing landscape of Chicago, from the hopeful migration era of the 40s and 50s to the crack-cocaine epidemic of the 90s, he acknowledged the complexities of progress. While acknowledging the struggles of the present, he emphasized the sacrifices of previous generations that paved the way for current opportunities. “We laid the ground, our sacrifices were big. But prior to that it was even worse. And look at the people who laid a platform for us.”

As a father of eleven, Mayfield considered the impact of contemporary music, particularly hip-hop and gangsta rap, on younger generations. He expressed concern about the explicit content and its potential influence on children. “I listen to it, and it hurts me. A lot of the stuff, as a grown adult and a father… well, you do have to lay down your own laws and not allow too much of it to infiltrate the home and family.” He stressed the importance of parental guidance and instilling strong values to counter negative influences. When asked if he would write about these contemporary issues, he responded, “No. It’s all been said. And I don’t like to repeat myself,” suggesting a sense of weariness with repeating social commentary, perhaps feeling the core messages of Curtis Mayfield songs already resonated.

Legacy and Enduring Voice

Despite multiple surgeries following his accident, Curtis Mayfield’s condition remained unchanged. He faced life confined to his bed, reliant on his family for basic needs. Yet, his mind and spirit remained vibrant. “We’re taught to keep high hopes,” he affirmed, embracing hope while acknowledging the reality of his situation. Frustrations arose from his inability to physically express his creative thoughts. “But if I have a thought, I can’t write it down. I even have a computer over there. But I can’t get up to use it. So there are those frustrations.”

His singing voice, once a powerful instrument behind Curtis Mayfield songs, was diminished. “Not in the manner as you once knew me. I’m strongest lying down like this. I don’t have a diaphragm any more. So when I sit up, I lose my voice. I have no strength, no volume, no falsetto voice, and I tire very fast.” However, the music within him persisted. “Yes, I do. I still come up with ideas and melodies. But they’re like dreams. If you can’t jot them down immediately, they vanish.”

Financial burdens from medical bills were substantial. A tribute album featuring renditions of Curtis Mayfield songs by renowned artists helped alleviate some of the costs. Royalty collection agencies like BMI also provided support. He expressed gratitude for the widespread assistance he received. “In my case lots of people have in their own ways been ready to come to my aid. I try not to ask. I don’t wish for charity. But I must still realise that I’m in need of everybody.”

His son, Todd Mayfield, exemplified the unwavering family support, acting as his father’s “legs and arms and part of my mind as well.” Despite immense adversity, Curtis Mayfield’s quiet strength and enduring spirit shone through. “So… so far, so good,” he concluded, a testament to his resilience.

Curtis Mayfield passed away on December 29, 1999, at the age of fifty-seven, leaving behind a legacy of powerful and poignant Curtis Mayfield songs. Before his death, he released one final album, New World Order, a testament to his unwavering creativity. His son Todd Mayfield’s biography, Traveling Soul, further illuminates the life and times of this extraordinary musical force, ensuring that the story and songs of Curtis Mayfield continue to inspire generations.

Share this:

Like Loading…